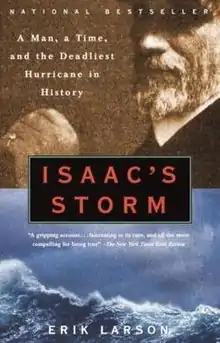

Cover | |

| Author | Erik Larson |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 2000 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 316 |

| ISBN | 0-609-60233-0 |

Isaac's Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History is a 2000 New York Times bestseller by Erik Larson presented in a non-fiction, novelistic style. The book follows the events immediately preceding, during, and after the 1900 Galveston hurricane.

The book is set in turn-of-the-century Galveston, Texas, a bustling port, placing a primary focus on the role of Isaac Cline in the hurricane's destruction of Galveston.[1]

Synopsis

The book opens with a restless Isaac Cline on the night of September 7, 1900, the eve of the 1900 Galveston hurricane's landfall. Isaac, despite all of the meteorological signs saying otherwise, cannot shake the uneasy feeling that something is amiss. Larson follows this prologue with a look at the science of hurricanes and all of the unusual factors that may have led to the hurricane that season. The initial birth of the storm is described with Larson's speculation on hurricane formation. Larson follows the path of the storm up to Galveston, while also looking at the people of Galveston and the vitality of the city. The narrative is supported by the insertion of letters and telegrams surrounding the events of the storm. The meteorologists of Cuba are shown to be very skilled in the art, but are completely ignored by the overconfident Weather Bureau and its meteorologists. The hurricane passes over Cuba, and the Cubans predict it to be heading towards Texas. The Weather Bureau, however, disagrees and believes that the storm will track towards Florida. Larson, meanwhile, looks at the lives of multiple Galveston residents on the eve of the storm, specifically Isaac Cline. He is a curious family man who risks his life to save his family.[1]

A storm begins to roll in and the streets begin to flood, not an unusual occurrence, but conditions soon worsen and the water continues to rise. Suddenly, from the mainland's view, Galveston goes quiet with no news or telegrams reaching anyone. Meanwhile, in Galveston, the storm literally uproots half the island and kills thousands, leaving utter destruction for the surviving. Rumors swirl on the mainland, and soon the full extent of the horror is realized. The islanders are left to rebuild their ruined city. Isaac has lost his wife and doubts himself some. The islanders rebuild the island, raising it by several feet in the process, but the city was never to return to its former glory with nearby Houston taking over Galveston's position as the prominent port in Texas.[1]

Isaac Cline

Isaac Monroe Cline (1861–1955) was the chief meteorologist at the Galveston, Texas office of the U.S. Weather Bureau from 1889 to 1901. Cline played an important role in influencing the storm's later destruction by authoring an article for the Galveston Daily News, in which he derided the idea of significant damage to Galveston from a hurricane as "a crazy idea". This article played a significant role in preventing the construction of a proposed seawall following the destruction of a competing port, Indianola, in the 1886 Indianola hurricane.[2]

Cline is credited during the 1900 hurricane with violating Weather Bureau policy and unilaterally issuing a hurricane warning; this warning, however, came too late to allow residents to evacuate the island. During the hurricane, Isaac went home to his pregnant wife, three daughters, and younger brother. There the Clines attempted to ride out the storm; however, the flood waters lifted the house and the family was separated for a time with Cline's wife, Cora, ultimately drowning.[3]

Awards

References

- 1 2 3 "Isaac's Storm". Isaac's Storm. Random House, Inc. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ Larson, Erik (1999). Isaac's Storm. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0-609-60233-0.

- ↑ Lutz, Heidi (2014). "The 1900 Storm: Tragedy and Triumph". The 1900 Storm. Galveston Newspapers Inc. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ↑ "About the Author". Erik Larson. Retrieved March 6, 2015.