Kalhíphona | |

|---|---|

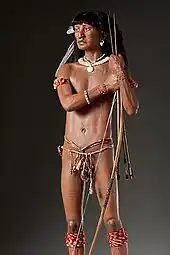

Carib family (by John Gabriel Stedman 1818) | |

| Total population | |

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Dominica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago; formerly throughout the Lesser Antilles | |

| Languages | |

| English, Dominican Creole French, formerly Island Carib | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Garifuna (Black Carib), Taíno |

The Kalinago, formerly known as Island Caribs[5] or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated language known as Island Carib.[6] They also spoke a pidgin language associated with the Mainland Caribs.[6]

At the time of Spanish contact, the Kalinago were one of the dominant groups in the Caribbean (the name of which is derived from "Carib", as the Kalinago were once called). They lived throughout north-eastern South America, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Windward Islands, Dominica, and possibly the southern Leeward Islands. Historically, it was thought their ancestors were mainland peoples who had conquered the islands from their previous inhabitants, the Igneri. However, linguistic and archaeological evidence contradicts the notion of a mass emigration and conquest; the Kalinago language appears not to have been Cariban, but like that of their neighbors, the Taíno. Irving Rouse and others suggest that a smaller group of mainland peoples migrated to the islands without displacing their inhabitants, eventually adopting the local language but retaining their traditions of a South American origin.[7]

In the early colonial period, the Kalinago had a reputation as warriors who raided neighboring islands. According to the tales of Spanish conquistadors, the Kalinago were cannibals who regularly ate roasted human flesh,[8] although this is considered by the community to be an offensive myth. This continues to be dismissed although there is evidence that the Island Caribs actually did practice cannibalism. [9] The Kalinago and their descendants continue to live in the Antilles, notably on the island of Dominica. The Garifuna, who share common ancestry with the Kalinago, also live principally in Central America.

Name

The exonym Caribe was first recorded by Christopher Columbus.[10]: vi One hypothesis for the origin of Carib is that it means "brave warrior".[10]: vi Its variants, including the English word Carib, were then adopted by other European languages.[10]: vi Early Spanish explorers and administrators used the terms Arawak and Caribs to distinguish the peoples of the Caribbean, with Carib reserved for indigenous groups that they considered hostile and Arawak for groups that they considered friendly.[11]: 121

The Kalinago language endonyms are Karifuna (singular) and Kalinago (plural).[12][13] The name was officially changed from 'Carib' to 'Kalinago' in Dominica in 2015.[14]

History

The Caribs are commonly believed to have migrated from the Orinoco River area in South America to settle in the Caribbean islands about 1200 CE, but an analysis of ancient DNA suggests that the Caribs had a common origin with contemporary groups in the Greater and Lesser Antilles.[15]

Pre-Columbian history

Over the two centuries leading up to Christopher Columbus's arrival in the Caribbean archipelago in 1492, the Caribs mostly displaced the Maipurean-speaking Taínos by warfare, extermination, and assimilation. The Taíno had settled the island chains earlier in history, migrating from the mainland.[16] The Taínos told Columbus that Caribs were fierce warriors and cannibals, who made frequent raids on the Taínos, often capturing women.[17][18]

Caribs traded with the Eastern Taíno of the Caribbean Islands.

In its early days, Daguao village was slated to be the capital of Puerto Rico but the area was destroyed by Caribs from neighbor-island Vieques and by Taínos, from the eastern area of Puerto Rico.[19]

The Kalinago produced the silver products found by Juan Ponce de León in Taíno communities. None of the insular Amerindians mined for gold but obtained it by trade from the mainland. The Kalinago were skilled boat builders and sailors. They appear to have owed their dominance in the Caribbean basin to their mastery of warfare.

Under the Spanish

According to Troy S. Floyd, "The question arose in Columbus's time as to whether Indians could be enslaved but Queen Isabel had ruled against it. At about the same time, however, Ojeda, Bastidas, and other explorers voyaging along the Spanish Main had been attacked by Indians with poisoned arrows – all such Indians were considered Caribs – which took a considerable toll of Spanish lives."

Resistance to the English and the French

In the 17th century, the Kalinago regularly attacked the plantations of the English and the French in the Leeward Islands. In the 1630s, planters from the Leewards conducted campaigns against the Kalinago, but with limited success. The Kalinago took advantage of divisions between the Europeans, to provide support to the French and the Dutch during wars in the 1650s, consolidating their independence as a result.[20] Such wars have led to a geopolitical boundary drawn separating the Lesser Antilles which they inhabit from Greater Antilles once settled by the Taíno known as the "poison arrow curtain".[21]

In 1660, France and England signed the Treaty of Saint Charles with Island Caribs, which stipulated that Caribs would evacuate all the Lesser Antilles except for Dominica and Saint Vincent, that were recognised as reserves. However, the English would later ignore the treaty, and pursue a campaign against the Kalinago in succeeding decades.[22] Between the 1660s and 1700, the English waged an intermittent campaign against the Kalinago.[6]

Chief Kairouane and his men from Grenada jumped off of the "Leapers Hill" rather than face slavery under the French invaders, serving as an iconic representation of the Carib spirit of resistance.[23][24][25]

By 1763, the British eventually annexed St Lucia, Tobago, Dominica and St Vincent.[20]

Modern-day Kalinago in the Windward Islands

To this day, a small population of around 3,000 Kalinago survives in the Kalinago Territory in northeast Dominica. Only 70 of them considered themselves as pure.[26]

People

The Kalinago of Dominica maintained their independence for many years by taking advantage of the island's rugged terrain. The island's east coast includes a 3,700-acre (15 km2) territory formerly known as the Carib Territory that was granted to the people by the British government in 1903. There are only 3,000 Kalinago remaining in Dominica. They elect their own chief. In July 2003, the Kalinago observed 100 Years of Territory, and in July 2014, Charles Williams was elected Kalinago Chief,[28] succeeding Chief Garnette Joseph.

Several hundred Carib descendants live in the U. S. Virgin Islands, St. Kitts & Nevis, Antigua & Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Trinidad and St. Vincent. "Black Caribs," the descendants of the mixture of Africans live in St. Vincent whose total population is unknown. Some ethnic Carib communities remain on the American mainland, in countries such as Guyana and Suriname in South America, and Belize in Central America. The size of these communities varies widely.

During the beginning of the 18th century, the Island Carib population in St. Vincent was greater than the one in Dominica. Both the Island Caribs (Yellow Caribs) and the Black Caribs (Garifuna) fought against the British during the Second Carib War. After the end of the war, the British deported the Garifuna (whose population consisted of 4,338 people) to Roatan island, while the Island Caribs (whose population consisted of 80 people) were allowed to stay on St. Vincent.[29] The 1812 eruption of La Soufrière destroyed the Carib territory, killing a majority of the Yellow Caribs. After the eruption, 130 Yellow Caribs and 59 Black Caribs survived on St. Vincent. Unable to recover from the damage caused by the eruption, 120 of the Yellow Caribs, under Captain Baptiste, emigrated to Trinidad. In 1830, the Carib population numbered less than 100.[30][31] The population made a remarkable recovery after that, although almost the entire tribe would die out during the 1902 eruption of La Soufrière.

Religion

The Caribs are believed to have practiced polytheism. As the Spanish began to colonise the Caribbean area, they wanted to convert the natives to Catholicism.[32] The Caribs destroyed a church of Franciscans in Aguada, Puerto Rico and killed five of its members, in 1579.[33]

Currently, the remaining Kalinago in Dominica practice parts of Catholicism through baptism of children. However, not all practice Christianity. Some Caribs worship their ancestors and believe them to have magical power over their crops. One strong religious belief Caribs possess is that Creoles practice a style of indigenous spirituality that has witchcraft-like elements.[34] Creole people are Caribs mixed with those who settled the island. An example of said people are Dominican Creoles, who speak a mix of French and the native Carib language.

Cannibalism

The Island Carib word karibna meant "person", although it became the origin of the English word "cannibal".[35] Among the Caribs karibna was apparently associated with ritual eating of war enemies. There is evidence supporting the taking of human trophies and the ritual cannibalism of war captives among both Arawak and other Amerindian groups such as the Carib and Tupinambá.[36]

The Caribs had a tradition of keeping bones of their ancestors in their houses. Missionaries, such as Père Jean Baptiste Labat and Cesar de Rochefort, described the practice as part of a belief that the ancestral spirits would always look after the bones and protect their descendants. The Caribs have been described by their various enemies as vicious and violent raiders. Rochefort stated they did not practice cannibalism.[37]

During his third voyage to North America in 1528, after exploring Florida, the Bahamas and the Lesser Antilles, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano was killed and is said to have been eaten by Carib natives on what is now Guadeloupe, near a place called Karukera (“island of beautiful waters”) . Historian William Riviere[38] has described most of the cannibalism as related to war rituals.

Medicine

The Kalinago are somewhat known for their extensive use of herbs for medicinal practices. Today, a combination of bush medicine and modern medicine is used by the Kalinago of Dominica. For example, various fruits and leaves are used to heal common ailments. For a sprain, oils from coconuts, snakes, and bay leaves are used to heal the injury. Formerly the Caribs used an extensive range of medicinal plant and animal products.[39]

Kalinago Canoes

Canoes are a significant aspect of the Kalinago's material culture and economy. They are used for transport from the Southern continent and islands of the Caribbean, as well as providing them with the ability to fish more efficiently and to grow their fishing industry. [40] Canoes, constructed from the Burseraceae, Cedrela odorata, Ceiba pentandra, and Hymenaea courbaril trees, serve different purposes depending on their height and thickness of the bark. The Ceiba pentandra tree is not only functional but spiritual and believed to house spirits that would become angered if disturbed. [41] Canoes have been used throughout the history of the Kalinago and have become a renewed interest within the manufacturing of traditional dugout canoes used for inter-island transportation and fishing. [42]

In 1997 Dominica Carib artist Jacob Frederick and Tortola artist Aragorn Dick Read set out to build a traditional canoe based on the fishing canoes still used in Dominica, Guadeloupe and Martinique. They launched a voyage by canoe to the Orinoco delta to meet up with the local Kalinago tribes, re-establishing cultural connections with the remaining Kalinago communities along the island chain, documented by the BBC in The Quest of the Carib Canoe.[43]

Notable Kalinagos

- Sylvanie Burton, president of Dominica since 2023.

- Liam Sebastien

- Kellyn George

- Tobi Jnohope

- Fitz Jolly

- Garth Joseph

- Audel Laville

- Lester Prosper

- Julian Wade

- Jay Emmanuel-Thomas

See also

References

- ↑ "Dominica's Kalinago fight to preserve their identity". BBC News. 15 July 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – St Vincent and the Grenadines". refworld. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – St Lucia". refworld. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Trinidad and Tobago". refworld. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "Change from Carib to Kalinago now official". Dominica News Online. 2015-02-22. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- 1 2 3 Haurholm-Larsen, Steffen (2016). A Grammar of Garifuna. University of Bern. pp. 7, 8, 9.

- ↑ Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

Island Carib.

- ↑ Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Study puts the 'Carib' in 'Caribbean,' boosting credibility of Columbus' cannibal claims".

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Christopher (2012). The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival and the Making of the Garifuna. Caribbean Studies Series. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781617033100. JSTOR j.ctt24hxr2.

- ↑ Kim, Julie Chun (2013). "The Caribs of St. Vincent and Indigenous Resistance during the Age of Revolutions". Early American Studies. 11 (1): 117–132. doi:10.1353/eam.2013.0007. JSTOR 23546705. S2CID 144195511.

- ↑ Greene, Oliver N. (2002). "Ethnicity, Modernity, and Retention in the Garifuna Punta". Black Music Research Journal. 22 (2): 189–216. doi:10.2307/1519956. JSTOR 1519956.

- ↑ Foster, Byron (1987). "Celebrating autonomy: the development of Garifuna ritual on St Vincent". Caribbean Quarterly. 33 (3/4): 75–83. doi:10.1080/00086495.1987.11671718. JSTOR 40654135.

- ↑ Admin (2015-02-22). "Change from Carib to Kalinago now official". Dominica News Online. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ↑ Mendisco, F.; Pemonge, M. H.; Leblay, E.; Romon, T.; Richard, G.; Courtaud, P.; Deguilloux, M. F. (2015). "Where are the Caribs? Ancient DNA from ceramic period human remains in the Lesser Antilles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. NCBI. 370 (1660). doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0388. PMC 4275895. PMID 25487339.

- ↑ Sweeney, James L. (2007). "Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent" Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, African Diaspora Archaeology Network, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, March 2007, retrieved 26 April 2007

- ↑ Figueredo, D. H. (2008). A Brief History of the Caribbean. Infobase Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1438108315.

- ↑ Deagan, Kathleen A. (2008). Columbus's Outpost Among the Taínos: Spain and America at La Isabela, 1493-1498. Yale University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0300133899.

- ↑ "La historia de Puerto Rico a través de sus barrios: Daguao de Naguabo (The history of Puerto Rico through its barrios: Daguao in Naguabo)" (video). www.pbslearningmedia.org (in Spanish). Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- 1 2 Hilary Beckles, "The 'Hub of Empire': The Caribbean and Britain in the Seventeenth Century", The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume 1 The Origins of Empire, ed. by Nicholas Canny (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 234.

- ↑ Floyd, Troy S. (1973). The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492-1526. University of New Mexico Press. p. 135.

- ↑ Delpuech, André (2001). Guadeloupe amérindienne. Paris: Monum, éditions du patrimoine. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9782858223671. OCLC 48617879.

- ↑ Newton, Melanie J. (2014). "Genocide, Narrative, And Indigenous Exile From the Caribbean Archipelago". Caribbean Quarterly. 60 (2): 5. doi:10.1080/00086495.2014.11671886. S2CID 163455608.

- ↑ Crouse, Nellis Maynard (1940). French pioneers in the West Indies, 1624–1664. New York: Columbia university press. p. 196.

- ↑ Margry, Pierre (1878). "Origines Francaises des Pays D'outre-mer, Les seigneurs de la Martinique" [French origins of overseas countries, the lords Martinique]. La Revue maritime (in French): 287–8.

- ↑ "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Dominica : Caribs".

- ↑ Ostler, Nicholas (2005). Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. Harper Collins. p. 362. ISBN 9780066210865.

- ↑ "Kalinago People | | a virtual Dominica". Archived from the original on October 26, 2010.

- ↑ Gargallo, Francesca (August 4, 2002). Garífuna, Garínagu, Caribe: historia de una nación libertaria. Siglo XXI. ISBN 9682323657 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Taylor, Chris (May 3, 2012). The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival, and the Making of the Garifuna. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781617033100 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Stanton, William (August 4, 2003). The Rapid Growth of Human Populations, 1750-2000: Histories, Consequences, Issues, Nation by Nation. multi-science publishing. ISBN 9780906522219 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Menhinick, Kevin, "The Caribs in Dominica" Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Copyright © Delphis Ltd. 1997–2011.

- ↑ Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 238. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ↑ "Carib, Island Carib, Kalinago People (Anthropology)". Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Cannibal". Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Whitehead, Neil L. (20 March 1984). "Carib cannibalism. The historical evidence". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 70 (1): 69–87. doi:10.3406/jsa.1984.2239.

- ↑ Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 22. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ↑ Historical Notes on Carib Territory Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, William (Para) Riviere, PhD, Historian

- ↑ Regan, Seann. "Healthcare Use Patterns in Dominica: Ethnomedical Integration in an Era of Biomedicine". Archived from the original on April 22, 2019.

- ↑ "Canoe Building". Indigenous Kalinago People of Dominica.

- ↑ Shearn, Issac (2020). "Canoe Societies in the Caribbean: Ethnography, Archaeology, and Ecology of Precolonial Canoe Manufacturing and Voyaging". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 57: 101140. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2019.101140. S2CID 213414242.

- ↑ Honychurch, Lennox (1997). Carib to Creole : contact and culture exchange in Dominica. University of Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Quest of the Carib Canoe". Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

Further reading

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, The Traveller's Tree, 1950, pp. 214–5

- Puerto Rico. Office of Historian (1949). Tesauro de datos historicos: indice compendioso de la literatura histórica de Puerto Rico, incluyendo algunos datos inéditos, periodísticos y cartográficos (in Spanish). Impr. del Gobierno de Puerto Rico. p. 22. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Allaire, Louis (1997). "The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles", in Samuel M. Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, pp. 180–185. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1531-6.

- Steele, Beverley A. (2003). Grenada, A history of its people, New York: Macmillan Education, pp. 11–47

- Honeychurch, Lennox, The Dominica Story, MacMillan Education, 1995.

- Davis, D and Goodwin R.C. "Island Carib Origins: Evidence and non-evidence", American Antiquity, vol.55 no.1(1990).

- Eaden, John, The Memoirs of Père Labat, 1693–1705, Frank Cass, 1970.

- (in French) Brard, R., Le dernier Caraïbe, Bordeaux : chez les principaux libraires, 1849, Manioc : Livres anciens | L E dernier caraïbe. Bordeaux.

External links

- Quest of the Carib Canoe - documentary

- The Quest of the Carib Canoe - dead link.

- Mainland Carib artwork, National Museum of the American Indians

- Yurumein (Homeland): A Documentary on Caribs in St. Vincent

- Guanaguanare - the Laughing Gull. Carib Indians in Trinidad - includes 2 videos

- "Carib", Ethnologue

- "Kalinago", Name change announcement of November 15, 2010, by the Office of the Kalinago Council posted at Dominica News Online