Sultanate of Jailolo كسلطانن جايلولو Kesultanan Jailolo, Jika ma-kolano | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th century?–1832 | |||||||

Jailolo and Halmahera | |||||||

| Capital | Jailolo | ||||||

| Common languages | Ternate | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (after late 1400s) | ||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||

| Sultan, Jika ma-kolano | |||||||

• before 1514 – 1530 | Raja Yusuf | ||||||

• 1536 – 1551 | Katarabumi | ||||||

• 1825 - 1832 | Muhammad Asgar | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Founded | 13th century? | ||||||

• Conversion to Islam | late 15th century | ||||||

• Vassalisation by Ternate | 1551 | ||||||

• Final ruler dethroned by Dutch | 1832 | ||||||

• Honorary sultan crowned | 2002 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||

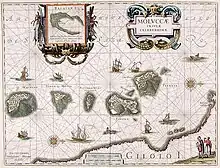

The Sultanate of Jailolo (كسلطانن جايلولو) was a premodern state in Maluku, modern Indonesia that emerged with the increasing trade in cloves in the Middle Ages. Also spelt Gilolo, it was one of the four kingdoms of Maluku together with Ternate, Tidore, and Bacan, having its center at a bay on the west side of Halmahera. Jailolo existed as an independent kingdom until 1551 and had separate rulers for periods after that date. A revivalist Raja Jailolo movement made for much social and political unrest in Maluku in the 19th century. In modern times the sultanate has been revived as a symbolic entity.[1]

Origins

Jailolo was a component in the politico-ritual quadripartition of northern Maluku, Maloko Kië Raha or the Four Mountains of Maluku. Its king was known as Jika ma-kolano, Ruler of the Bay, highlighting the Jailolo Bay as the major port in Halmahera. It is locally believed that the kingdom encompassed the entire island or at least the major part. However, in historical times it only ruled over part of Halmahera while the rest was dominated by the spice sultanates Ternate and Tidore. It emerged long before the introduction of Islam (1460s or 1470s), but the concrete history of the kingdom can only be followed since the early 16th century, and the pre-Islamic era is only known via later traditions. The oldest available version was written down by the Dutch priest François Valentijn (1724), long after the demise of the sultanate. Valentijn relates that Jailolo was a strong kingdom in Halmahera by 1250, and that the oppressive governance of the king (Kolano) caused an exodus of people to Ternate, an island to the south-west of the Jailolo Bay, where a new trade-oriented kingdom emerged in 1257.[2] In the following centuries Jailolo and Ternate had intermittent conflicts with shifting success. In the early 14th century, Tidore and the Bacan Islands also chose rulers of their own. The four kings eventually held a meeting on Moti Island in the 1320s where they agreed to create a bond where the Kolano of Jailolo would have the precedence position. In spite of this, warfare flared up from time to time and Jailolo's position was not always respected. According to Valentijn a Ternatan prince married the daughter of the King of Jailolo in c. 1375 and succeeded to the throne since the old ruler had no sons. Nevertheless, a later Ternatan ruler called Komalo Pulo (1377-1432) conquered some villages on Halmahera and forced the King of Jailolo to cede his precedence position.[3]

Another set of legends tells that an Arab immigrant called Jafar Sadik came to Maluku and married a heavenly nymph called Nurus Safa, daughter of the Lord of Heaven. The couple sired four sons called Buka, Darajat, Sahajat and Mashur-ma-lamo, who became the ancestors of the kings of Bacan, Jailolo, Tidore, and Ternate. Darajat was first established on Moti Island and then moved to the Jailolo Bay and set up a royal seat there.[4] He was followed by fifteen descendants, the last of whom was a certain Talabuddin.[5] Only a few persons in the list can be positively identified with rulers from contemporary historical sources.

The oldest Malukan chronicle, Hikayat Tanah Hitu (mid-17th century), says that Islam was introduced in the late 15th century by Mahadum, who was the son of a Sultan of Samudra Pasai. Mahadum performed missionary work in several places in Indonesia and successively traveled in eastern direction. Via the Banda Islands he proceeded to Jailolo whose king he converted and gave the name Yusuf. From there he went to the nearby Tidore and Ternate islands where he was equally successful.[6] The Hikayat Tanah Hitu also mentions a power struggle between two elite lineages around 1500. The losing side emigrated from Jailolo to Hitu in Ambon Island where their leader Jamilu became a renowned Muslim chief who fought the Portuguese invaders.[7]

The early kings

The first Muslim ruler Yusuf is in fact a well-documented person who was in power when the Portuguese and Spanish seafarers arrived to Maluku in search of spices and made contact with the Portuguese in 1514.[8] Tomé Pires, in his geographical work Suma Oriental (c. 1515) confirms that Jailolo and Ternate were often at war, and writes that much wild clove grew in the kingdom, which was still largely heathen in spite of the king being a Muslim. Jailolo was in fact the only real port in Halmahera, though the clove production was centered on the smaller islands Ternate, Tidore, Moti and Makian along Halmahera's west coast.[9] Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition, who visited Maluku in 1521–1522, says that there were two Muslim kings in Jailolo Island (that is, Halmahera), each with several hundred wives. There was also a Raja Papua who was lord over the heathen people in Halmahera and had much access to gold. One of the Muslim rulers was Raja Yusuf who was a close ally with Tidore and was feared and respected in the Maluku Islands.[10] As a consequence of this alliance, Jailolo also allied with the Spanish who were periodically posted in Tidore, and opposed the might of Portugal which had built a stronghold in Ternate in 1522-23 and tried to appropriate the clove trade. With the help of Spanish munitions and weapon technology, Jailolo expanded its influence in Halmahera at the cost of Ternate.[11]

The old and ailing Yusuf died in 1530, leaving a son of 5–6 years called Sultan Firuz Alauddin Syah as the titular ruler.[12] However, he appointed two nephews called Kaicili Tidore and Kaicili Katarabumi to act as regents. Katarabumi had previously lived in exile since he claimed the right to the kingdom and had even tried to murder the old king, but was nevertheless pardoned and placed in a position of power.[13] The new Portuguese captain in Ternate, Tristão de Atayde eventually had enough of the Jailolo-Spanish alliance and attacked and destroyed the royal center in 1533. The small Spanish detachment in Jailolo gave up without a fight. The young Firuz was brought to Ternate where he was later poisoned by his captors with the understanding of Katarabumi, who seized the throne in about 1536.[14] Being a strong Muslim, he nevertheless turned out to become a major opponent of European influence in the region. He allied with the Tobaru people in northern Halmahera and violently attacked areas hitherto under Ternate.[15] When he invaded Gamkonora and the recently Christianized villages in Morotai and Morotia (in north Halmahera), he invoked the enmity of the Portuguese, who made strong proselytizing efforts to spread Catholicism. By this time the immediate sphere of the kingdom had about 4,000 able-bodied men. It produced much foodstuff but little or no cloves, and therefore never gained the economic importance of Ternate or Tidore.[16]

Katarabumi earned a widespread reputation in Maluku for being a ruler with outstanding capabilities, and was seen as a “second Muhammad”. Among his achievements was the invention of a script to write down the local language; unfortunately, no such texts have been preserved.[17] He resided in a stone fort close to the Jailolo Bay that was considered impenetrable and was garrisoned by 1,200 soldiers of whom 100 were musketeers. The defiant stance of Katarabumi eventually led to an invasion in Halmahera by the Portuguese Captain Bernaldim de Sousa and Sultan Hairun of Ternate. Jailolo fell after a long siege in March 1551, after provisions had run out. The conditions of surrender were hard; Katarabumi lost the title of Kolano or king and had to be content with the lesser title Sangaji ("honoured prince", regional lord). He must also honour Sultan Hairun as his suzerain. The fortress was thoroughly destroyed. With these events the independent Jailolo sultanate came to an end.[18] In order to avoid actual subjugation to Ternate, Katarabumi and his family left the main residence and moved to a simple dwelling in the forest, while the Portuguese tried in vain to persuade him to hail Hairun. However, most of his retainers acknowledged Ternate's power, and the old and destitute ruler died in 1552 after taking poison.[19]

Vassal under Ternate

Katarabumi left three sons and three daughters, of whom Kaicili Gujarati succeeded him as Sangaji. He must agree to deliver large tributes of sago and other items. For Ternate, Jailolo with its large hinterland became important as deliverer of foodstuff. The Portuguese had a low opinion about his personal qualities. However, in 1558 Captain Duarte d’Eça found reason to give him back the title of Sultan in order to enlist his help against the rebellious Ternatans. The rebellion receded in 1559-1560 as Sultan Hairun made an agreement with the Portuguese. However, Hairun took a severe revenge on Kaicili Gujarati in about 1560 as he was attacked on a sea trip by a Ternatan fleet and killed with arrows together with part of the nobility of the kingdom.[20]

Very little is known about Jailolo after this incident. At the time when Hairun himself was murdered by the Portuguese in 1570, Jailolo was governed by an offspring of his sister whose name is not known, but who assisted Hairun's son Babullah in fighting the Portuguese.[21] The vassal status of the Jailolo princes was henceforth sealed by regular marriages with the Ternatan Sultan's family, where Ternate acted as wife-givers. Towards the end of the 16th century an unnamed ruler was forced by his brother to flee Jailolo and settle with his brother-in-law, the Sultan of Brunei, with his mother and daughters. The Flemish traveler Jacques de Coutre met him in Brunei in 1597 and gave him medical advice.[22] The next known ruler was Kodrat who married Babullah's daughter Ainalyakin and governed until about 1605. The pair sired Doa who was born around 1593 and succeeded his father as vassal ruler in about 1606.[23] Doa married his cousin, a daughter of Sultan Saidi Berkat and fought with the latter's son Sultan Mudafar Syah I against the Spanish invaders who conquered Ternate in April 1606 in alliance with the Sultan of Tidore. During the struggle Jailolo was also captured by the enemy in 1611 and Doa and his followers moved over to Ternate, which for the most part had been recaptured with Dutch assistance in 1607. This meant that Jailolo ceased to be the seat of a vassal king.[24] In April 1613 a Ternatan fleet of kora-koras (large outriggers) clashed with a fleet from Tidore. The gunpowder kept in a large kora-kora was lit and the vessel exploded whereby Doa and two Ternatan princes succumbed.[25] In 1620 the Spaniards nevertheless left their post in Jailolo to the care of the Tidorese, who in turn were unable to hold the place against the Dutch-backed Ternate.[26]

Prince Doa and the Ternate princess had a son whose personal name is unclear but who later appeared as the Raja Jailolo.[27] He was a man of some ability who married a stepdaughter of Sultan Hamza of Ternate.[28] This prince took part on the side of the rebels in the Great Ambon War where dissatisfied Malukans fought the monopolistic Dutch East India Company from 1651 to 1656. He served as the foremost adviser for the Ternatan rebel prince Kalamata who tried to gain power with the help of the Makassarese and briefly resided in Jailolo in 1652–1653. At the close of this war, that ravaged parts of Central Maluku extensively, Raja Jailolo was captured by a Dutch officer off the coast of Buru Island in 1656. Together with 25 followers he was killed in cold blood and thrown into the sea.[29] He left a son called Kaicili Alam who inherited the claim to be Raja Jailolo. Alam was an apt figure who held the function of Gogugu (first minister) in Ternate and married Mahir Gam-ma-lamo, a daughter of Sultan Mandar Syah. The Sultan of Tidore, Saifuddin, believed that four Malukan kingdoms were necessary to restore the region to its old prosperity. He therefore asked the Dutch Governor Padtbrugge to enthrone Alam as Sultan Jailolo. However, Alam died in 1684 and ideas of a restoration were put to rest for a century.[30] The old possessions of Jailolo on Halmahera continued to be administered by Ternate, now securely under Dutch colonial tutelage. According to one source the last Kolano was a person called Doa who was deposed by the local grandees due to mismanagement. He then fled to Ternate where he died around 1715. After this, the Ternatan court did not appoint any new Kolano but charged the foremost village leader with the governing tasks.[31] However, local genealogies identify a large number of descendants of the old sultans up to modern times.[32] A person called Giolo turned up in England around 1692 and claimed to be a son of the King of Jailolo. According to his story, he and his parents were captured by pirates and enslaved by a ruler of Tomini on Sulawesi.[33] In fact, Giolo appears to have been a Filipino slave who claimed royal connections.[34]

The Raja Jailolo movement

Dissatisfaction with the intrusive policy of the Dutch East India Company led to a rebellion in Maluku and Papua after 1780, which was headed by the Tidore prince Nuku. Nuku shared the old vision of a return to the four kingdoms of Maluku, Maloko Kië Raha, which required the restoration of the Sultanate of Jailolo. A former Jojau (chief minister) of Tidore called Muhammad Arif Bila, originally from Makian, traced his pedigree from Alam[35] and was groomed by Nuku as throne candidate. When Nuku temporarily managed to take control over Jailolo in 1796 he formally enthroned Muhammad Arif Bila, thus recreating the old quadripartition. His dignity was confirmed in the next year when Nuku captured Tidore and became Sultan.[36] Whether the Jailolo sultanate was still in living memory among the population of Halmahera is unclear; the restoration was in fact a way by Nuku to strengthen his position vis-à-vis the Dutch-allied Ternate and Bacan.[37] As Nuku negotiated with the Dutch in Ternate in 1804, he demanded that they should recognize the position of Muhammad Arif Bila. When they refused to do so, Nuku and Muhammad Arif Bila invaded Halmahera with a fleet of 47 kora-koras and summoned the local elite to a conference to anchor their claims. Sultan Jailolo set out to subjugate the old domains of the kingdom in 1804–1805, but did not succeed entirely.[38] His protector Nuku died in the same year and the new Sultan of Tidore, Zainal Abidin, did not have the same influence. The Dutch struck back and conquered Tidore Island in 1806 and Zainal Abidin and Muhammad Arif Bila had to flee to Halmahera. The latter hid in the forests of Mount Kia with his family, but was killed when he fell in a ravine; according to his son he was treacherously assassinated by Ternatans.[39]

Muhammad Arif Bila left several children of whom Muhammad Asgar inherited the pretensions to Jailolo and resided in Bicole. However, the Dutch possessions in Maluku were captured by the English East India Company in 1810, and the British promptly arrested the pretender-Sultan in 1811 and kept him in custody in Ambon, since they had no interest in maintaining the Raja Jailolo movement. Meanwhile, his brothers Hajuddin, Sugi and Niru turned to piracy and raided the waters of Sulawesi with the help of warriors from Halmahera and the Papuan Islands. While the Raja Jailolo movement had failed to create a new kingdom, the idea of a fourth Moluccan kingdom gained currency in Halmahera and gave rise to new forms of anti-colonial resistance.[40]

When the Dutch returned to power in Maluku in 1817, Muhammad Asgar petitioned the colonial government to be restored to royal powers. The argument was that the people wished for a return to the old kingdom, and that a central ruler would unite the Halmaherans and stop the widespread piracy and unrest. This was ignored by the Dutch officials who exiled the pretender-Sultan to Java. Nevertheless, his brother Hajuddin was now proclaimed Sultan of Jailolo in 1818 or 1819 and began to raid the central parts of Maluku. He established a stronghold in Kobi on the north coast of Ceram, later moved to Waru and finally to Hatiling. The Dutch sent a few expeditions to capture him in 1819-1820 but failed to do so. Instead, the following of the Sultan grew as many people from the Ternatan and Tidorese parts of Halmahera migrated to his domain in Ceram, escaping oppressive conditions at home. The Papuan Islands and West Papua were also influenced by the Raja Jailolo movement, and the Sultan was even able to cooperate with the pirates of Maguindanao in southern Philippines.[41] The Governor of Ambon, P. Merkus, tried in vain to stop the widespread piracy, which continued after Hatiling had been captured in 1823, As a last resort he finally called back the ex-sultan Muhammad Asgar from Java in 1825. The idea was to stabilize the area by making him the head of the Halmaherans living in northern Ceram. He was formally called “Sultan Ceram” since Hajuddin kept the title of Jailolo ruler. The experiment was however a failure since the adherents of the Raja Jailolo movement persisted in piratical activities and the area where the Halmaheran had migrated was unhealthy. Eventually the Dutch arrested Sultan Ceram and Sultan Jailolo in 1832 and exiled them to Cianjur in Java. Muhammad Asgar died there in 1839 while Hajuddin died in 1843.[42] This was the definitive end of the sultanate, and the Halmaherans largely left for their home island; however, the unrest continued with widespread piracy and slaving that was not entirely suppressed until the early 20th century.[43]

Later rebel movements

In fact there were a few further attempts to revive the Jailolo state, since the rule of Ternate and Tidore in Halmahera remained oppressive. A grandnephew of the last Sultan Jailolo, Dano Baba Hasan, left his home in Ambon in 1875 and started to make followers in eastern Halmahera. People under his influence resisted Ternate and Tidore, but not the colonial system as such. In fact Baba Hasan tried to win Dutch support to reestablish Jailolo. However, the colonial authorities were bound by their contracts with the Malukan sultans and were not in a mood to alter the political order.[44] Baba Hasan was proclaimed Sultan Jailolo in June 1876 and was able to dominate wide regions on the island such as Weda, Maba, Patani and Gane. Now the Dutch stepped in and destroyed the rebel fleet at Papile. The uprising was finally suppressed when the sultan surrendered himself on 21 June 1877. Dano Baba Hasan was exiled to Muntok off Sumatra where he died in 1895.[45]

A last effort was made by a relative of Baba Hasan called Dano Jayudin, also from Ambon. In 1914 he took up residence in the Weda district in south-eastern Halmahera. Waigeo, one of the Papuan Islands, sent tributary gifts to him, before a police brigade made a quick end to the attempt to recreate Jailolo.[46]

Modern revivalism

The position of Jailolo was not an issue for a long time. However, at the end of the 20th century a wave of revivalism for old royal traditions (sultanism) emerged in Indonesia. Ternate enthroned a new titular sultan in 1986 and Tidore followed suit in 1999. The reformation era after the fall of the Suharto regime with its emphasis on bureaucratic centralization, was more allowing for local cultural expressions. Thus the idea of the four peaks of Maluku, Maloko Kië Raha began to be reshaped. During the period 2002–2017, four titular sultans were elevated to power in succession, namely Abdullah Sjah, Ilham Dano Toka, Muhammad Siddik Kaitjil Sjah, and Ahmad Abdullah Sjah, though not without internal local disputes about the right selection.[47]

See also

References

- ↑ Kirsten Jäger (2018) Das Sultanat Jailolo: Die Revitalisierung von "traditionellen" politischen Gemeinwesen in Indonesien. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

- ↑ François Valentijn (1724) Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien, Vol. I. Amsterdam: Onder den Linden, p. 134-5.

- ↑ François Valentijn (1724), p. 138-9

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987) Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, Vol. I, p. 16-8.

- ↑ Noegroho, A. (1957) "'Tjatatan perdjalanan' dari Provinsi Irian Barat di Soa-Sio, Tidore", Mimbar Penerangan VIII:8, p. 563 .

- ↑ Christiaan van Fraassen (1987), Vol. II, p. 5-6.

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 470.

- ↑ Artur Basilio de Sá (1954) Documentação para a história das missões Padroado portugues do Oriente, Vol. I. Lisboa: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, p. 113.

- ↑ Tomé Pires (1944) The Suma Oriental. London: The Hakluyt society, p. 221.

- ↑ Antonio Pigafetta (1874) The first voyage round the world, by Magellan. London: Hakluyt Society, p. 133.

- ↑ Leonard Andaya (1993) The world of Maluku. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, p. 122.

- ↑ Artur Basilio de Sá (1954), p. 253.

- ↑ M.F. de Navarrete (1837) Colección de los viages y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles desde fines del siglo 15. Madrid: Imprenta Nacional, p. 141.

- ↑ Leonard Y. Andaya (1993), p. 122; P.A. Tiele (1877-1887) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 25-35, Part 2:2, p. 20.

- ↑ Georg Schurhammer (1980) Francis Xavier: His Life, his times - vol. 3: Indonesia and India, 1545-1549. Rome: The Jesuits Historical Institute, p. 63-88.

- ↑ Artur Basilio de Sá (1954), p. 321.

- ↑ P.A. Tiele (1877-1887) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 25-36, Part 3:5, p. 319.

- ↑ Leonard Y. Andaya (1993), p. 130.

- ↑ Hubert Jacobs (1974) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. I. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 4*, 90-2, 187-8.

- ↑ Daniello Bartoli (1879) L'Asia, Vol. VI. Milano: Pressa Serafino Majocchi Librajo, p. 95.; Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson (1906) The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898, Vol. 34. Cleveland: A.H. Clark Company, p. 201-1.

- ↑ Francisco Colin & Pablo Pastells (1900) Labor evangelica, ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compañia de Iesvs, fvndacion, y progressos de su provincia en las islas Filipinas, Vol. III. Barcelona: Henrich y Compañia, p. 54.

- ↑ Peter Borschberg (ed.) (2014) The memoirs and memorials of Jacques de Coutre. Singapore: NUS Press, p. 149-50.

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Ternate, de Molukken en de Indonesische Archipel. Leiden: Rijksmuseum te Leiden, Vol. II, p. 22.

- ↑ Naïdah (1878) "Geschiedenis van Ternate", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 4:1, p. 444.

- ↑ P.A. Tiele (1877-1887) "De Europëers in den Maleischen Archipel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 25-35, Part 8:2, p. 270.

- ↑ Hubert Jacobs (1984) Documenta Malucensia, Vol. III. Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, p. 412.

- ↑ Referred to as "Saiuddin" in https://www.worldstatesmen.org/Indonesia_princely_states2.html .

- ↑ P.A. Tiele & J.E. Heeres (1887-1895) Bouwstoffen voor de geschiedenis der Nederlanders in den Maleischen Archipel, Vol. II. 's Gravenhage: Nijhoff, p. 238-9.

- ↑ Georg Rumphius (1910) "De Ambonsche historie, Tweede deel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 64, p. 101-2.

- ↑ Leonard Y. Andaya (1993), p. 173.

- ↑ T.J. Willer (1849) "Aanteekeningen omtrent het noorder-schiereiland van het eiland Halmahera", Indisch Archief 1, p. 358.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1984) "The idea of a 4th kingdom in 19th century Maluku", in Maluku dan Irian Jaya. Jakarta, p. 180; Busranto Latif Doa (2009) "The hidden history of Jailolo"

- ↑ Thomas Hyde (1692) An account of the famous Prince Giolo, son of the King of Gilolo, now in England. London: R. Taylor.

- ↑ Gayatri Madkaikar, "Mysterious tattooed man called ‘Painted Prince’ turns out to be a Filipino slave", https://noonecares.me/mysterious-tattooed-man-called-painted-prince-turns-out-to-be-a-filipino-slave/

- ↑ Sejarah singkat kerajaan/kesultanan Jailolo https://northmelanesian.blogspot.com/2012/04/sejarah-kerajaan-jailolo.html

- ↑ Leonard Y. Andaya (1993), p. 235-6.

- ↑ Muridan Widjojo (2009) The revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-cultural alliance-making in Maluku, c. 1780-1810. Leiden: Brill, p. 82-3.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1984), p. 181-2.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1984), p. 183-4.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1984), p. 185.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1984), p. 185-8.

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 58.

- ↑ R.Z. Leirissa (1996) Halmahera Timur dan Raja Jailolo: Pergolakan Sekitar Laut Seram Awal Abad 19. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 59.

- ↑ M. Adnan Amal (2016) Kepulauan rempah-rempah: Perjalanan sejarah Maluku Utara 1250-1950. Jakarta: Gramedia, p. 48.

- ↑ C.F. van Fraassen (1987), Vol. I, p. 473.

- ↑ Kirsten Jäger (2018).