| 1945 Katsuyama killing incident | |

|---|---|

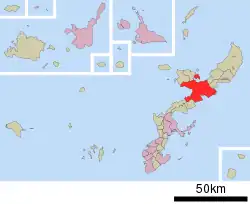

| Location | Nago, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan |

| Date | July 10, 1945 |

Attack type | Vigilantism |

| Weapon | Knives |

| Deaths | 3 |

| Victim | African-American Marines |

| Perpetrators | Japanese soldiers and civilians |

| Motive | To stop rape incidents |

The 1945 Katsuyama killing incident was the killing of three African-American United States Marines in Katsuyama near Nago, Okinawa after the Battle of Okinawa on July 10, 1945, to August 13, 1946. Residents of Katsuyama had reportedly killed the three Marines for their repeated rape of village women during occupation of Okinawa and hid their bodies in a nearby cave out of fear for retaliation.[1] The Katsuyama incident was kept secret until August 16, 1997, when the bodies and identities of the Marines were discovered.[1]

Incident

In June 1945, Allied victory at the major Battle of Okinawa led to the occupation of the highly-strategic Okinawa Prefecture of Japan shortly before the end of the Pacific War. Reportedly, three African-American Marines of the United States Marines Corps began to repeatedly visit the village of Katsuyama, northwest of the city of Nago, and every time they violently took the village women into the nearby hills and raped them. The Marines became so confident that the villagers of Katsuyama were powerless to stop them, they came to the village without their weapons.[2]

The villagers took advantage of this and ambushed them with the help of two armed Imperial Japanese Army soldiers who were hiding in the nearby jungle.[2] Shinsei Higa, who was sixteen at the time, remembers that "I didn't see the actual killing because I was hiding in the mountains above, but I heard five or six gunshots and then a lot of footsteps and commotion. By late afternoon, we came down from the mountains and then everyone knew what had happened."[1]

The Marines were killed and, to cover up their deaths, their bodies were dumped in a local cave which had a 50-foot (15-m) drop-off close to its entrance. In the summer of 1947, when the three Marines did not return to their posts, they were listed as possible deserters. After a year with still no evidence of what happened to them, they were declared missing in action.[1][3] Knowledge of the killings became a village secret for the next 50 years, remaining secret for the duration of the United States Military Government and the United States Civil Administration, until 1972, when the U.S. government returned the islands to Japanese administration.

Discovery

Kijun Kishimoto, a villager who was almost 30 years old and absent from Katsuyama at the time of the incident, eventually revealed the killings. In an interview, Kishimoto said, "People were very afraid that if the Americans found out what happened there would be retaliation, so they decided to keep it a secret to protect those involved."[1] Finally, a guilty conscience led Kishimoto to contact Setsuko Inafuku (稲福節子), a tour guide for Kadena United States Air Base in Okinawa, whose deceased son Clive was also a victim of sexual assault, and who was involved in the search for deceased servicemen from the war.[1]

In June 1997, Kishimoto and Inafuku searched for the cave near Katsuyama, but could not find it until August when a storm blew down a tree which had been blocking the entrance.[1] Kishimoto and Inafuku informed the Japanese police in Okinawa but they kept the discovery a secret for a few months to protect the people who discovered the location of the bodies.

The Katsuyama incident was reported to the United States military by Inafuku, who informed then-Kadena Air Base 18th Wing Historian Master-Sergeant James Allender, who in turn reported it to the Joint Services Central Identification Laboratory at Pearl Harbor. Once the bodies were recovered by the United States Army, the three Marines were identified using dental records as Private First Class James D. Robinson of Savannah, Private First Class John M. Smith of Cincinnati, and Private Isaac Stokes of Chicago, all aged 19 or 20 years-old.[1] The cause of death could not be determined.[4]

Aftermath

No plans were made to criminally investigate the Katsuyama incident by either the United States military or the Okinawa police. Since the killings, locals have allegedly called the cave Kuronbō Gama (黒ん坊がま). In Okinawan language, Gama refers to a cave.[5] Kuronbō (黒ん坊) is a derogatory and highly offensive word for Black people in Japanese.[6]

The Katsuyama incident has been seen by opponents of U.S. military presence in Okinawa as one of many examples of misconduct by American personnel against Okinawans since the islands were first occupied after the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Steve Rabson, Professor of East Asian Studies at Brown University, estimated that as many as 10,000 such instances of rape occurred after the war. Under the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, the United States Forces Japan has maintained a large military presence in Okinawa: 27,000 personnel, including 15,000 Marines, contingents from the Army, United States Navy, United States Air Force, and their 22,000 family members.[7]

See also

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- 1955 Yumiko-chan incident

- 1995 Okinawa rape incident

- 2002 Okinawa Michael Brown assault incident

- 2006 Yokosuka homicide

- 2008 Yokosuka homicide

General:

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sims 2000

- 1 2 Cullen 2001

- ↑ American Battle Monuments Commission

- ↑ Talmadge 2000

- ↑ "がまの解説". dictionary.goo.ne.jp. January 31, 2023.

沖縄地方や鹿児島などの方言。

- ↑ Talmadge 2000: "Locals call it Kuronbō Gama. Gama means cave. Kuronbo (黒んぼ) is an ethnic slur referring to black people."

- ↑ "沖縄県の基地の現状" (PDF) (in Japanese). Naha City, Okinawa: Okinawa Prefectural Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

References

- American Battle Monuments Commission. "James W. Grimmett". Arlington, Virginia: American Battle Monuments Commission. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Cullen, Lisa Takeuchi (August 13, 2001). "Okinawa Nights". TIME. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Sims, Calvin (June 1, 2000). "3 Dead Marines and a Secret of Wartime Okinawa". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- Talmadge, Eric (May 7, 2000). "Okinawa legend leaves unsettling questions about Marines' deaths". Athens Banner-Herald. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

Further reading

- Dower, John W. (2000). Embracing Defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II (2000 ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32027-5.

- Russell, John (1991). "Race and Reflexivity: The Black Other in Contemporary Japanese Mass Culture". Cultural Anthropology. 6 (1): 3–25. doi:10.1525/can.1991.6.1.02a00010. ISSN 0886-7356. JSTOR 656493. S2CID 146155382 – via JSTOR.

- Svoboda, Terese (May 23, 2009). "U.S. Courts-Martial in Occupation Japan: Rape, Race, and Censorship". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 21-1-09. ISSN 1557-4660. Retrieved October 25, 2010.