Jean-Baptiste Denys | |

|---|---|

| Jean-Baptiste Denis | |

| |

| Born | c. 1635 |

| Died | October 3, 1704 Paris, France |

| Alma mater | University of Montpellier, Collège des Grassins |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, Philosophy |

| Patrons | Henri Louis Habert de Montmor |

Jean-Baptiste Denys (c. 1635 – 3 October 1704) was a French physician[1] notable for having performed the first fully documented human blood transfusion, a xenotransfusion. He studied in Montpellier and was the personal physician to King Louis XIV.

Early life

Jean-Baptiste Denys was born in the 1630s, although his birth went unnoticed and undocumented. His father was an artisan who specialized in water pumps, which were seeing an increase in popularity and sophistication during the time of his birth. Denys' passion for medicine was also influenced due to his own suffering from asthma.[2]

Education

Denys obtained a bachelor's in theology at the Collège des Grassins and a medical degree from the Faculty of Medicine in Montpellier. Denys’ ambition drew him to attempt a career in Paris, but the university's poor reputation made him an outsider to the Paris's wealthy scientific elite.

In Paris, he settled among the medical students in the Latin Quarter, to whom he would give anatomy lessons, encouraging the same hands-on approach as the Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius. These lectures were primarily given to establish important connections within Paris's medical community, and they provided Denys with little income.

General context

The years 1667 and 1668 were characterized by the growing frenzy over the possibility of blood transfusion.

The French and English were the main contestants in the battle to perform the first successful human blood transfusion. Members of the British Royal Society began by injecting doses of fluids into the veins of animals, proceeding with dog-to-dog transfusion. Similarly, the French Academy of Science tried canine experiments, but was unable to replicate the English success.

Attempts at blood transfusion

Denys started a collaboration with the barber-surgeon Paul Emmerez (died 1690) to undertake blood transfusion, having been influenced by reports of English success. During one of his dissections, he shared with his students his belief that transfusion was the ‘new and completely convincing proof’ of the truth of circulation, who in contrast degraded him.

His first recorded case of blood transfusion was between two small dogs, both of which he intended to survive the procedure, in contrast to the results obtained by the English. Approximately nine ounces of blood was transfused from one dog to the other during this experiment. In his writings, Denys stated that one of the dogs suddenly weakened measurably, leading to the termination of the experiment. One dog remained weak while the other maintained a more energetic and alert character, although Denys did note that the dog was not as ‘awake and gay' as it had been earlier. The physician then performed a control experiment with a third dog of similar characteristics with those prior. This was done to ensure that recorded effects, such as eye movement, food consumption, and the weights of the subjects were consistent among all three dogs and did not change due to outside elements.

Denys believed that blood transfusion would garner him recognition throughout all of Europe and the Parisian elite. On March 9, 1667, he made an announcement in the journal des sçavans, stating his intention to publicize his anatomical and experimental demonstrations of blood transfusion as a therapeutic tool. This established Denys as the primary transfusionist of France, thus going against the ideals of the Academy of Sciences of Paris, Faculty of Medicine, and those of Charles Perrault.

Denys later moved his research to the private academy established by Henri Louis Habert de Montmor, who saw an opportunity to surpass both the English and the conservative French Academy of Sciences and consequently gain his own glory. Denys and Emmerez, with the new funds and supplies, progressed their experiments on dogs with various techniques and points of transfusion. They regarded them all as successful, as of the nineteen dogs recorded, none died. They also focused on interspecies transfusion, starting in early April 1667 with transfusions between calves and dogs, then moving on to sheep, cows, horses, and goats.

Denys would go on to announce his successes to the European scientific community through written reports submitted to the Journal des sçavans, which enabled him to start a correspondence with Henry Oldenburg, and consequently the Philosophical Transaction. He omitted to credit the works done by English scientists, leading to many conflicts. He believed the next step was initiating a radical new procedure between humans and animals, utilizing as a prime example the lamb, the symbol of the blood of Christ, hence the purest form.

Human attempts

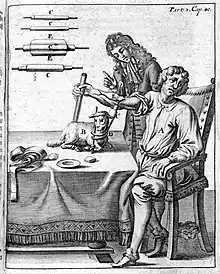

Denys administered the first full documented xenotransfusion on June 15, 1667. With the assistance of Paul Emmerez he transfused about twelve ounces of lamb blood into the veins of a 15-year-old boy who had suffered from uncontrollable fevers for two months and had been consequently bled with leeches 20 times by a barber-surgeon, to no effect. After Denys’ intervention, allegedly, by the next morning, the boy was alert, and seemingly cured of his illness.

He performed another transfusion on a middle-aged butcher with pleasing results. The man had not died and was found to be in great spirit. Realistically, both instances of success were most likely due to the small amount of blood that was actually transfused into these people, which did not trigger any major allergic reaction.

Antoine Mauroy

Sometime in November 1667, Mauroy was abducted from the streets of Paris by Montmor's guard and tied to a chair and transfused with blood in front of an audience of noblemen. In the hours following the procedure, Mauroy experienced a debilitating fever, nausea, diarrhea, nosebleeds, and urine that was as black as ‘chimney soot’, fever, tachycardia, and abundant sweating. Just days later, the man had apparently fully recovered. This was the final proof for Denys, who immediately publicized his success, firstly by writing to Oldenburg, who published the letters received on the February 10, 1668 edition of the Philosophical Transactions[3] (original and translated).

Mauroy and his wife eventually returned to their modest home, but Perrine soon found out that her husband's newfound calmness was temporary, lasting only two months. The man's state of health and mind changed abruptly due to his binges of wine, tobacco, and 'strong waters' (alcohol). The man's madness was worse than before.

Denys performed a second transfusion which diminished the delirium but induced other major side effects. The third and last transfusion performed on Mauroy happened under major pressure of the wife, in fact, Denys was against it. During the procedure, Mauroy's body, at a certain point, shook in a ‘violent fit’ to which the men decided to end the transfusion. Mauroy died the next day.

Reportedly no blood had actually been transfused into Mauroy and the calf had not yet been cut open when the seizures started. Denys and Emmerez tried to perform an autopsy but they were strongly opposed by the wife.

Trial

Following Antoine Mauroy's death, a case was formed on April 17, 1668, and presented to the Court of Grand Châtelet. Denys was convinced that his transfusions did not cause Mauroy's death, and that this trial was rather a consequence of his decision to pursue research against the will of the King's Academy of Sciences as well as that of the major players of the conservative Parisienne Faculty of Medicine.

In an attempt to prove his innocence, Denys described his medical experiments to Commissioner Le Cerf and explained their safety, which was supported by the many survivors willing to witness in his favor. Finding sufficient grounds for concern, La Cerf forwarded the case to the Criminal Lieutenant, the Honorable Jacques Defita, for a full hearing.

The witnesses at the trial included Perrine Mauroy, Mauroy's late wife, allegedly, persuaded and offered large amounts of money by several "unknown" physicians, to bear false witness and file reports against Denys’ blood transfusion experiments. Following a police investigation, vials with arsenic powder were found in Perrine Mauroy's possession. Arsenic poisoning was known to harm the nervous system and cause symptoms such as tremors, seizures and delirium; this could therefore explain Mauroy's intense delusional behavior prior to the third transfusion. It was therefore suspected that Perrine Mauroy had been administering arsenic powder to her husband's broth.

Judge Defita cleared Denys of all accusations and Perrine was charged and sent to the Grand Châtelets prison. No further investigation was carried out on Perrine's accomplices, whom Denys referred to as ‘Enemies of the Experiment’. In addition, the judge ordered that “no transfusion should be made upon any human body but by the approbation of the physicians of the Parisian Faculty (of Medicine)”, forcing Denys to end his studies in blood transfusions.[2]

After the Trial

After the trial, Denys tried to rebuild his reputation as a transfusionist but the verdict impaired his efforts. Nonetheless, the appeal he made was given full consideration. The only transcript of the hearing suggests that the argument made by Denys’ lawyer, Chrétien de Lamoignin, was considered a masterpiece; yet, the whole procedure was surprisingly short followed by no discussion.

The verdict was again against the practice of blood transfusion. The judge declared that transfusions could only be performed with the express approval of the Paris Faculty of Medicine, a remarkably remote occurrence.

Denis returned to his home on the Left Bank, where he resumed the paid lectures to students he gave prior to beginning transfusions. Four years after the final trial at parliament, he invented styptic, an antihemorrhagic liquid, now common around the world.[2]

Denys’ Haemostatic Solution

In 1673, a series of experiments of a newly-invented substance created by Denys, referred to as ‘Liqueur hémostatique’ or 'Essence de Denys', were presented to Henry Oldenburg (1619–1677), secretary of the English Royal Society and editor of Philosophical Transactions, in London. It supposedly held anti-hemorrhagic properties. Interest within the medical field grew after accounts of his successful demonstrations were reported in ‘Philosophical Transactions’, a publication by the English Royal Society dating back to mid-1673.[4] Denys claimed that his ‘essence’ was much simpler to use compared to earlier methods of cautery which involved the use of caustic agents such as the ‘needle and thread’ and ‘hot iron’. Denys' 'essence', of which the contents are unknown, is believed to contain a mixture of potassium alum and sulfuric acid, would be applied to arterial and venous wounds in order to staunch the bleeding. Recognizing the effectiveness of the 'essence' and foreshadowing the potential usefulness in the English army, Denys received recognition by King Charles II and was invited to stay with him in London as his First Physician, an offer which Denys declined in order to return to Paris in November 1673. This was probably the last mention of the ‘essence’ ever since.

The first fully documented experiment using Denys’ blood staunching liquor was carried out on May 30, 1673 in London by English physician Walter Needham and surgeon Richard Wiseman. In an attempt to demonstrate the effectiveness of the 'essence', Needham cut open a dog's neck exposing the jugular vein and carotid artery. He then applied Denys' hemostatic liquor to the bleeding vessels and applied pressure using a pledget for 30 minutes. Upon removal of the pledge, free-flowing bleeding was no longer observed—the artery had been staunched. Under the order of King Charles II, the two proceeded to test the liquor on patients at the St Thomas' Hospital in Southwark, London; the same results were obtained.[3]

Death

Denys died in 1704 at the age of 69.

Further reading

- Tucker, Holly (2012). Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393342239.

References

- ↑ "This Month in Anesthesia History". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- 1 2 3 Tucker, Holly (2012). Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 222. ISBN 978-0393342239.

- 1 2 Denis, Monsieur (1673). "Experimens of a Present and Safe way of Staunching by a Liquor the Blood of Arteries as Well as Veins; Made Both in London and Paris". Philosophical Transactions. 8: 6052–6059. JSTOR 101354 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "Jean-Baptiste Denis • Medical Eponym Library". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2021-05-04.