| Dolly Sods Wilderness | |

|---|---|

| |

Location of Dolly Sods Wilderness in West Virginia | |

| Location | West Virginia, United States |

| Coordinates | 38°59′45″N 79°22′05″W / 38.99583°N 79.36806°W |

| Area | 17,776 acres (71.94 km2)[2] |

| Elevation | 2,500 to 4,700 ft (760 to 1,430 m) |

| Established | January 3, 1975[2] |

| Operator | Monongahela National Forest |

| Website | Dolly Sods Wilderness |

The Dolly Sods Wilderness (DSW, originally simply Dolly Sods) is a U.S. Wilderness Area in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern West Virginia and is part of the Monongahela National Forest of the U.S. Forest Service.

Dolly Sods is a rocky, high-altitude plateau with sweeping vistas and lifeforms normally found much farther north in Canada. To the north, the distinctive landscape of "the Sods" is characterized by stunted ("flagged") trees, wind-carved boulders, heath barrens, grassy meadows created in the last century by logging and fires, and sphagnum bogs that are much older. To the south, a dense cove forest occupies the branched canyon incised by the North Fork of Red Creek.

The name derives from an 18th-century German homesteading family, the Dahles, and a local term for an open mountaintop meadow, a "sods".

Geography

Topography

Dolly Sods is the highest plateau east of the Mississippi River with altitudes ranging from 2,644 ft. (806 m) at the outlet of Red Creek to 4,123 ft. (1,257 m) at the top of the eastern edge mountain ridge on the Allegheny Front. Much of the high plateau section lies at nearly 4,000 ft.(1,220 m) elevation. Prominent summits within the wilderness are Coal Knob (3,766 ft (1,148 m)), Breathed Mountain (3,848 ft (1,173 m)), and Blackbird Knob (3,960 ft (1,210 m)). The highest point in the immediate area (just outside the Dolly Sods Wilderness area in the Roaring Plains West Wilderness) is Mount Porte Crayon (4,770 ft (1,450 m)). The summit area around Mount Porte Crayon is the largest flat-topped plateau in Eastern North America containing 5.5 square miles (14.2 square kilometers) above 4,500 ft. (1,372 m) elevation.

Drainage

Dolly Sods is on a ridge crest that forms part of the Eastern Continental Divide. Most of its area is drained by the North Fork of Red Creek, which is a tributary of the Dry Fork River. Via the Dry Fork, Black Fork, Cheat, Monongahela and Ohio rivers, it is part of the Mississippi River watershed. South of Forest Service Route 19 is the adjoining Red Creek–Flatrock–Roaring Plains area, which is drained by the South Fork of Red Creek. Drainage on the east side of the ridge crest flows into the headwaters of the South Branch Potomac River, which is part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Boundaries

The original Dolly Sods was a mountaintop meadow of about 650 acres (3 km2) at the southern end of Rohrbaugh Plains, near the present Dolly Sods Picnic Area.[3] The present-day DSW encompasses some 17,371 acres (70 km2) of U.S. Forest Service land and is part of a larger 32,000-acre (129 km2) area now known as "Dolly Sods".[2][4] The DSW is bordered by Forest Service Routes 75 and 19 on the east and south sides, respectively. (Since the early 1970s it has been common practice to include the Red Creek Plains, Flatrock Plains, and Roaring Plains areas to the south as part of the greater Dolly Sods area. Formerly, the area encompassed by these three mountaintop flats – all south of FS Rt 19 – was known locally and collectively as Huckleberry Plain.[5])

To the northeast, DSW is bordered by the Bear Rocks Preserve, owned by The Nature Conservancy. The surrounding area was recently added to the wilderness and is known as Dolly Sods North (the high sods). North of Dolly Sods North (and just outside the present DSW) is an area known as Dobbins Slashings—a sub-arctic bog forming the headwaters of Red Creek on Cabin Mountain. Dobbins Slashings has also been proposed for wilderness preservation. In the Canaan Valley to the west, the DSW is adjoined by the 16,000-acre (65 km2) Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge. Almost all of DSW is in the southeast corner of Tucker County with only very small sections extending into Randolph and Grant Counties.

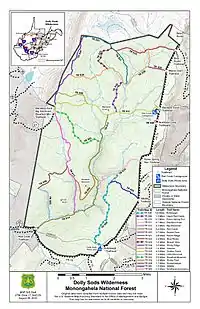

Trails

There are some 47 miles (76 km) of hiking trails within the DSW (see below), many situated along the courses of abandoned railroad grades and old logging roads. The premier viewpoint within the wilderness, affording a vista of the entire Red Creek drainage, is at a set of rocky crags known as Lion's Head Rock. It is reached by an almost three-mile climb from the nearest road. The last quarter mile is an eight-foot-wide bench (an old railroad grade) in the side of an otherwise steep slope. Like the cliffs constituting the eastern edge of the DSW at Rohrbaugh Plains, Lion's Head Rock consists of a mixture of sandstone and conglomerate. The Northland Loop Trail is a 0.3 mile interpretive trail just south of Red Creek Campground on FS Rt 75 which accesses Alder Run Bog a typical, and much studied, northern bog or southern muskeg.[6]

History

Pre-logging

The Dolly Sods area was first encountered by Europeans when Peter Jefferson, Thomas Lewis and others surveyed in 1746 to find the limits of Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron's land grant from the British Crown. The famous Fairfax Line grazes the northern margin of the wilderness near Bear Rocks. This area was generally avoided as too difficult to traverse until the late 19th century. David Hunter Strother wrote an early and somewhat breathless travelogue of the area, published in Harper's Monthly magazine in 1852:

In Randolph County, Virginia, is a tract of country containing from seven to nine hundred square miles, entirely uninhabited, and so savage and inaccessible that it has rarely been penetrated even by the most adventurous. The settlers on its borders speak of it with a sort of dread, and regard it as an ill-omened region, filled with bears, panthers, impassable laurel-brakes, and dangerous precipices. Stories are told of hunters having ventured too far, becoming entangled, and perishing in its intricate labyrinths. The desire of daring the unknown dangers of this mysterious region, stimulated a party of gentlemen . . . to undertake it in June, 1851. They did actually penetrate the country as far as the Falls of the Blackwater, and returned with marvelous accounts of its savage grandeur, and the quantities of game and fish to be found there.

The name Dolly Sods derives from the family name of Johann Dahle (1749–1847), a German immigrant who settled nearby. Such early settlers utilized the natural open fields on mountainsides known as "sods". Logged out and burned over areas produced additional good grass cover for grazing sheep and cattle. (Repeated burning, however, killed the grass and left only bracken fern, which was useless as fodder.) Locals changed the spelling of Dahle to "Dolly," and thus one such area became known as Dolly Sods. The Dahle family eventually moved on, leaving behind only the Americanized version of their name.

Local historian Hu Maxwell described the Dolly Sods area in the Wheeling Intelligencer in 1886: "The top of the mountain is flat, except here and there rugged ridges and huge promontories of rocks rising above the level of the plains, and giving the scene an appearance of distance and mystery that must be witnessed before it can be understood".[7]

Johann Dahle (John Dolly) was born on 6 September 1749 in Hesse, Germany, and came to America as a Hessian soldier in the service of the British army, then fighting against General George Washington's Continental Army. Serving under General Cornwallis, he was captured at Yorktown (1781), the battle which effectively ended the war, and was imprisoned for a time at Winchester, Virginia. In the 1780s he settled on the west side of North Fork Mountain in what later became Pendleton County. (A family tradition maintains that he was advised by Washington himself to remain in Virginia.) There he purchased land, married (for a second time) and began a family (9 children in all). He was a farmer and a miller and went by the nicknames of "Cornyackle" and "Barleycorn". Eventually the family land holdings in Pendleton and the surrounding area grew to several hundred acres which may have included what later became known as scenic "Dolly Sods". It is said that Dolly and his descendants grazed their cattle and sheep in these high grassland patches. Certainly they harvested blueberries at the southern end of the flats known as Rohrbaugh Plains. John Dolly continued to live in his adopted home until his death, at nearly 100 years of age, in August 1847. He left many descendants, none of whom remain, however, near the old homestead.[8]

Logging era

The area surrounding Dolly Sods was formerly described as the best spruce-hemlock-black cherry forest in the world, with some enormous trees up to 12 feet in diameter. The huge spruce and hemlock became accessible in 1884 when the West Virginia Central and Pittsburgh Railroad, a predecessor of the Western Maryland Railway, first arrived at nearby Davis, from a junction with the B&O Railroad at Piedmont. In 1899, the Parsons Pulp and Lumber Company (PPLC) established a sawmill at Dobbin on the North Branch Potomac River in Grant County. In 1902, the PPLC installed a new band saw mill on the main stem of Red Creek. The lumber boom town of Laneville soon sprang up around it with a population that peaked at over 300 people.[9]Shay locomotives climbed the temporary railroads into the mountains and backcountry logging camps sprang up throughout the Sods, clearing away the virgin forest to feed the hungry mills. Teams of draft horses dragged all the commercial timber to the nearest tracks. When the timber was exhausted in the sector around one camp, the rails were taken up and reused elsewhere. It was into the mill at Laneville that most of the timber of the southern two thirds of the Sods disappeared.

Unfortunately, however, the humus covering the ground dried up when the protective tree cover was removed. Sparks from the locomotives, saw mills and logger's warming fires easily ignited this humus layer and the extensive slash – wood too small to be marketable, such as branches and tree crowns – left behind by loggers. Fires repeatedly ravaged the area in the 1910s, scorching everything right down to the underlying rocks. All insects, worms, salamanders, mice and other burrowing forms of life perished and the area became a desert. The destruction was extraordinary.[10] The complete clearcut of this ecologically fragile area, followed by extensive wildfires and overgrazing, exacerbated by the ecological stresses of the elevation, have prevented quick regeneration of the forest which has taken decades to recover. The Monongahela National Forest was created in 1915, largely motivated by a desire to mitigate the sort of wholesale destruction that had swept over the Sods. In 1916 most of Dolly Sods was purchased by the federal government for the MNF from the Bridges Estate. Mineral rights remained in private ownership.[11]

The Laneville mill closed in 1920 after almost all the timber had been cut and the local population dwindled. The last timber was felled in the Dolly Sods area in 1924. A particularly ferocious fire raged in late July 1930 in the northernmost Red Creek and southernmost Stony River watersheds (along the Grant/Tucker County line). This conflagration – known as the Dobbin Slashings Fire – consumed 24,800 acres (100 km2) and killed many trees left alone as non-commercial by the loggers. An eerie landscape persisted here for years, with the stumps of these trees perched high upon jumbles of boulders.

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps made some modest attempts to remediate the damage to Dolly Sods by re-planting stands of red spruce there.

Army use and cleanup

In 1943 and '44, as part of the West Virginia Maneuver Area, the U.S. Army used the area as a practice artillery and mortar range and maneuver area before troops were sent to Europe to fight in World War II; with Cabin Mountain and Blackbird Knob serving as designated targets.

In 1997, a work crew extensively surveyed trail locations and known campsites for shells.[12] Workers made 32,594 excavations along the trails and discovered and detonated 14 live mortar shells, most along the Fisher Spring Run Trail. All were exploded on site. Two others were inert. They also found numerous railroad spikes, iron tools and horseshoes left over from logging days. Off-trail searches proved to be impossible,[13] so some of the artillery and mortar shells (60 mm and 81 mm rounds) shot into the area likely still remain there. (See this link for a photo of two shells found in July 2006.)

Threat and recovery

Dolly Sods became popular with recreationalists and conservationists in the mid-1960s at which time political agitation began to set it aside as a preserve. Local farmers also ceased allowing their livestock to graze here at this time.

Nevertheless, the area was threatened by at least four potential developments:

- sub-divisions for summer homes on Cabin Mountain,

- as a route for a proposed federal expressway (Corridor H) linking Washington, DC with the highlands,

- strip-mining of as many as six coal seams, which was already occurring within 3.5 miles of the Sods in the north and

- flooding by a huge reservoir as part of the proposed Davis Power Project just to the west.

An ad hoc committee of stakeholders was convened by the MNF in Spring 1969. It advised that a scenic or botanical area should be set aside in the North Fork Red Creek area. In October 1970, the Forest superintendent announced the creation of 10,200-acre (41 km2) "Dolly Sods Scenic Area".

The Nature Conservancy played a major role in preserving the area. By 1972, it had purchased the coal rights under the future federal wilderness (15,558 acres (63 km2) of the Sods and Roaring Plains, itself now a designated Wilderness) for $15 million. Dolly Sods finally became a federally designated wilderness area in 1975 which resulted in greatly increased numbers of visitors. The area had only an estimated 500 visitors in 1965; by 1997 there were 7,499 registered (and many more unregistered) users annually.

In the 1970s and '80s, it was not possible to propose Dolly Sods North for wilderness classification as it was all privately owned – by the Western Maryland Railway Company and the Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO) – and was largely outside the proclamation boundary of the MNF. Public acquisition could not go forward as the companies long refused to consider selling. In 1993, however, the Nature Conservancy paid another $6 million to acquire 6,168 acres (25 km2) in Dolly Sods North (of the total of 7,215 acres (29 km2)) from the then-owner, the Texas-based Quintana Corporation. This land was then donated to the Forest Service.[14] Most recently, the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009 added 7,156 acres (29 km2) of Dolly Sods North to the original 10,215 acres (41 km2) of the Wilderness to make the present total of 17,371 acres (70 km2).[4]

Climate and weather

The climate of Dolly Sods is classified as humid continental, similar to portions of Canada. Daily weather can vary greatly with large extremes in temperature occurring dangerously fast. Fog can form/roll in extremely quickly, dropping visibility to dangerous, disorienting near-zero conditions. Access roads can quickly become blocked by dense fog, downed trees from high wind, and snow/snow drifts.

Summers are cool and wet. At 4,000 feet (1,220 m), the average afternoon maximum is around 70 °F (21 °C) and the average morning minimum is in the 50s (10-15 °C). Thunderstorms are frequent during the warmer months. Frosts and freezes can occur any month of the year. Winters are typically cold, windy, and snowy. Minimum temperatures can drop to -30 °F (-34 °C). The average seasonal snowfall is estimated to be around 150 inches (381 cm). In exceptionally snowy winters, large drifts of up to 20 ft (7 m) can form, lasting in sheltered locations into May. Due to high elevation, frequently located at cloud level, spectacular rime ice is frequently seen totally coating the forest in pure white.

Despite the overall vigorous winter, the relative southern location (39th North parallel) allows for occasional intrusions of warmer, well above freezing air from the Gulf of Mexico. Thus, rain can occur during even the coldest winter months. During one of the snowiest winters in history (2009–10), about 275 inches (700 cm) of snow is estimated to have fallen above 4,000 feet (1,220 m).

This section of the Allegheny Front is one of the windiest spots east of the Mississippi. The effect of these winds can be seen in the flag-form red spruce trees; their branches grow mostly on one side (east), away from the prevailing west winds. Because of the drying influence of the winds, stunted branches are produced on the west side of the tree above the protective shrub layer. Stunted branches on the east side give the trees a twisted appearance. Where spruce are protected by a shrub layer, luxuriant webs of branches extend for a radius of a dozen feet, giving a mat-like look to vegetation.[15]

Ecology

Flora

Dolly Sods is well known for its open expanses of sphagnum bog, heath shrubs and scattered and stunted red spruce – all creating impressions of areas much farther north. Many plant communities are indeed similar to those of sea-level eastern Canada. But the ecosystems within the Sods are remarkably varied. In recent decades, the many stages of ecologic succession throughout the Sods have made the region one of enduring interest to botanists.

Sods (grass balds)

The local term "sods" is a traditional name referring to several high-elevation meadows in the High Alleghenies. The term is virtually synonymous with the "grass bald" of the southern Appalachians. These grassy areas on mountain slopes or summits apparently existed by the scores in the mid-Appalachian region when first discovered . According to botanist Earl L. Core, "The silvery sheen of the grass, against the dark green background of the spruce, attracted the attention of the early settlers.... The dominant grass is Allegheny flyback (Danthonia compressa), a grass so light in weight that it would "fly back" against the scythe of the mower".[16] The origin of these grassy tracts has been the subject of wide-ranging speculation. Core favored a multi-factorial explanation involving a "bald-susceptible zone" present at mountain summits where various causes (extreme weather, fires, etc.) initially wiped out trees followed by succession by grasses that was so competitive with the new tree seedlings that the cleared areas persist for a much longer period than at lower elevations.

Heath barrens (huckleberry plains)

The extensive views across the tundra-like windswept open meadows in the northern section of Dolly Sods are reminiscent of Alaskan landscapes. "Heath barrens" is a botanical term, but the traditional local name for these unusual expanses was "huckleberry plains". These upper reaches have been extensively colonized by various Ericaceae (heaths): blueberry and cranberry (Vaccinium), huckleberry (Gaylussacia), rose azalea (Rhododendron prinophyllum) and rosebay rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum), mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), teaberry (or wintergreen, Gaultheria), and Allegheny menziesia (Rhododendron pilosum). Members of Rosaceae (the rose family) also abound: chokeberry, mountain ash, serviceberry, and pin cherry (Prunus pensylvanica). Boulder fields left by the denuding topsoil fires of 80 years ago are extensive here.

Sphagnum glades (cranberry bogs)

These spruce-edged sphagnum bogs are found in the upper sections of Red Creek and its tributaries, often in association with thickets of speckled alder. There are similar areas throughout the High Alleghenies, most famously the Cranberry Glades. The largest one at Dolly Sods is about a mile long and half a mile wide. The thick carpet of sphagnum moss and the polytrichum moss hummocks also sustain cotton grass, round leaf sundew and the lichen known as reindeer moss. In addition to the spruce, the bog margins are frequented by ferns, sedges and the occasional balsam fir. The three-toothed cinquefoil (Sibbaldiopsis tridentata) is often abundant and orchids – for example the pink lady's slipper – are sometimes seen.[17]

Hardwood forests

The more southerly section of the Dolly Sods Wilderness includes maturing spruce copses, rhododendron thickets, northern hardwoods on the ridges and cove hardwoods in the deep tributaries of Red Creek. All of the original old-growth forest was removed a century ago, followed by fires that burned, then smoldered, for months. Much of the deep topsoil was lost forever. Today, there are patches of recovering native red spruce forest plus twisted yellow birch, sugar and red maple, eastern hemlock, and black cherry. American beech, pine and hickory can also be found. The wild onion known as the ramp (Allium tricoccum) is also present in the deeper forests.

Fauna

The larger megafauna which once inhabited the High Alleghenies – elk, bison, mountain lion – were all exterminated during the 19th century. They survived longer in this area, however, than in other parts of the eastern United States. Because of the high altitude the climate is cool and some animals are more similar to ones found about 1,600 miles (2,600 km) farther north in Canada. Many species found here are near their southernmost range. For example, the snowshoe hare found in Dolly Sods is usually found in Canada and Alaska and is adapted to snow conditions, with its large, hairy feet which allow it to run on the snow surface.

Beaver – which were restored to the state after a period of extirpation – continually create and refurbish their beaver ponds in these high elevation watersheds. Other animals that may be encountered include red and gray foxes, bobcats, black bears, groundhog, timber rattlers, wild turkey, and grouse. White-tailed deer, also once eliminated from the region, were reintroduced in the 1930s and are now abundant. Currently, the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources is considering an elk restoration program in Dolly Sods and other areas.[18] The Cheat Mountain salamander, listed since 1989 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as threatened, is also present.

Recreation

Camping is allowed in Dolly Sods, but visitors are cautioned to "leave no trace". All off-road motorized vehicles and any cutting of live vegetation or camping near roads (aside from Red Creek Campground) are forbidden. Hunting and fishing within state law are permitted. Dolly Sods is particularly popular during mid-summer with people who go there to pick blueberries and huckleberries. From May through late June, extensive and spectacular displays of mountain laurel in flower may be viewed. Due to severe winter weather, FS Rt 75, flanking the eastern side of Dolly Sods, is typically closed to vehicles from January 1 to April 15.

There is an extensive network of hiking trails in the Wilderness totalling 47 miles. Some follow old logging railroad grades, and occasionally you see some remnants of railroad ties and metal equipment. Because USGS and USFS maps of the trails have been inaccurate, a 2004 mapping site provides good maps based on GPS data. Trails include:

- Dolly Sods

- Wildlife Trail

- Rohrbaugh Plains Trail

- Red Creek Trail

- Fisher Spring Run Trail

- Big Stonecoal Trail

- Little Stonecoal Trail

- Dunkebarger Trail

- Rocky Ridge Trail

- Breathed Mountain Trail

- Dolly Sods North

- Beaver View Trail

- Blackbird Knob Trail

- Bear Rocks Trail

- Raven Ridge Trail

- Dobbin Grade Trail

- Upper Red Creek Trail

- Flatrock–Roaring Plains

- South Prong Trail

- Boars Nest Trail

- Roaring Plains Trail

- Flatrock Run Trail

The Spruce Knob–Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area is adjacent to Dolly Sods–Flatrock–Roaring Plains on the east and the south.

Gallery

Red Creek near its confluence with Fisher Spring Run

Red Creek near its confluence with Fisher Spring Run View looking east from the Allegheny Front near Bear Rocks

View looking east from the Allegheny Front near Bear Rocks Backpackers embarking

Backpackers embarking Wetlands at Dolly Sods

Wetlands at Dolly Sods One of many extensive exposed rock fields at the sods

One of many extensive exposed rock fields at the sods Bracken undergrowth

Bracken undergrowth Trail sign in Dolly Sods North

Trail sign in Dolly Sods North Mountain laurel

Mountain laurel Fall foliage

Fall foliage Sundew in the sods

Sundew in the sods On Fisher Spring Run Trail

On Fisher Spring Run Trail A branch of Red Creek

A branch of Red Creek Bazzania trilobata on rocks in Tsuga canadensis forest at the sods

Bazzania trilobata on rocks in Tsuga canadensis forest at the sods Blackbird Knob trail becomes impassable due to a flash flood on Red Creek

Blackbird Knob trail becomes impassable due to a flash flood on Red Creek Ferns in autumn, October 2023

Ferns in autumn, October 2023

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Dolly Sods Wilderness". Protected Planet. IUCN. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Dolly Sods Wilderness". Monongahela National Forest. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ↑ Wilderness Committee, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, The Dolly Sods Area – 32,000 Acres in and Adjacent to the Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia, 4th edition; Revised Sept 1973, pg 7.

- 1 2 "Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009". Library of Congress. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ↑ Brooks, Maurice (1965), The Appalachians (Series: The Naturalist's America), Illustrated by Lois Darling and Lo Brooks, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, pp 187-188.

- ↑ Gibson, Joan R. (1970). "The Flora of Alder Run Bog, Tucker County, West Virginia". Castanea. 35 (2): 81–98. JSTOR 4032484.

- ↑ Quoted in Core, Earl L. (1973), "Allegheny Flyback at Dahle Sods", Charleston Gazette-Mail, 29 July; Reprinted in the same author's 1975 book The Wondrous Year: West Virginia Through the Seasons, Grantsville, West Virginia: Seneca Books, pg 91.

- ↑ Imhoff, Ernest F (1998), "Land of Spruce and Mortar Shells", The Baltimore Sun: Sun Journal, March 17 issue. Dolly and his wife are buried at Dolly Hills, near Mouth of Seneca, in Pendleton, County, West Virginia (Landis-Dolly Cemetery #50, Pendleton County. Grave Register II.).

- ↑ Wilderness Committee, Op. cit., pg 5.

- ↑ More than one-tenth of the area of the state of West Virginia was burned over in this way, including one-fifth of the forest areas.

- ↑ Wilderness Committee, Op. cit., pg 7.

- ↑ On 3 December 1951, 17-year-old Wally Dean and a companion chanced upon a mortar round while hiking in the Sods. Upon dropping it, Dean was blown into a tree and suffered nine shrapnel wounds to his legs. This necessitated the surgical placement of metal wires and plates. In 1997, Dean, by then an environmental projects engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, directed the cleanup of some of the treacherous rounds.

- ↑ Imhoff, Op. cit.

- ↑ de Hart, Allen and Bruce Sundquist (2006), Monongahela National Forest Hiking Guide, 8th edition, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, Charleston, West Virginia, pg 124.

- ↑ West Virginia Renewable Resources Unique Areas Series 813

- ↑ Core, Earl L. (1974), The Monongalia Story: A Bicentennial History, Vol. I: Prelude, Parsons, W. Va.: McClain Printing Co., pp 55-56.

- ↑ Brooks, Op. cit., pp 187-188.

- ↑ McCoy, John. "Elk on the way?". wvgazette.com.

Other sources

- Brooks, Maurice, "Remarkable Dolly Sods" (1969–70), Outdoor West Virginia [Title changed to Wonderful West Virginia, 1970]; Nov 1969, pp 10–13; Jan 1970, pp 10–13; Feb 1970, pp 10–13.

- Hall, George A. (1985), "The Birds of the Dolly Sods Area Sortie, 1984", The Redstart, Wheeling, West Virginia, October issue.

- Hutton, Eugene E. (1988), "Periglacial Features of Dolly Sods,", The Redstart, Wheeling, West Virginia, July issue.

- Hutton, Eugene E. (1985), "Plant Description of Dolly Sods,", The Redstart, Wheeling, West Virginia, October issue.

- Keating, Steve (2010), A Dolly Sods North - Blackwater Companion: A Guide to Hiking Through the History, Geology and Ecology of the Region; Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing.

- O'Neil, L. Peat (1998), "Wonder in the Tundra. W. Va.'s Dolly Sods is a wilderness worth a look", The Washington Post, September 16, p D-9.

- Pyle, Ann H. (1985), "Ferns and Fern Allies at Dolly Sods,", The Redstart, Wheeling, West Virginia, October issue.

- Venable, Norma Jean (1996), Dolly Sods, West Virginia Renewable Resources Unique Areas Series 813, West Virginia University Extension Service, Morgantown, West Virginia.

- U.S. Forest Service (1988), Dolly Sods Wilderness and Surrounding Area, pamphlet.

External links

- Dolly Sods Wilderness at the U.S. Forest Service

- Dolly Sods at American Byways

- Dolly Sods Forest Walk at Forests of the Central Appalachian Project

- Dolly Sods at Wilderness

- Webcam of Dolly Sods Wilderness