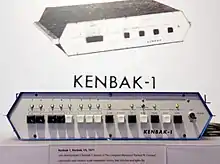

A Kenbak-1 at the Computer History Museum | |

| Developer | John Blankenbaker |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Kenbak Corporation |

| Type | Personal computer |

| Release date | 1971 |

| Introductory price | US$750 (equivalent to $5,420 in 2022) |

| Discontinued | 1973 |

| Units sold | 44[1] |

| Memory | 256 bytes of memory |

The Kenbak-1 is considered by the Computer History Museum,[2] the Computer Museum of America[3] and the American Computer Museum[4] to be the world's first "personal computer",[5] invented by John Blankenbaker (born 1929) of Kenbak Corporation in 1970 and first sold in early 1971.[6] Less than 50 machines were ever built, using Bud Industries enclosures as a housing.[1] The system first sold for US$750.[7] Today, only 14 machines are known to exist worldwide,[8][9] in the hands of various collectors and museums. Production of the Kenbak-1 stopped in 1973,[10] as Kenbak failed and was taken over by CTI Education Products, Inc. CTI rebranded the inventory and renamed it the 5050, though sales remained elusive.[11]

Since the Kenbak-1 was invented before the first microprocessor, the machine didn't have a one-chip CPU but was instead based purely on small-scale integration TTL chips.[12] The 8-bit machine offered 256 bytes of memory,[13] implemented on Intel's type 1404A silicon gate MOS shift registers.[14] The clock signal period was 1 microsecond (equivalent to a clock speed of 1 MHz), but the program speed averaged below 1,000 instructions per second due the many clock cycles needed for each operation and slow access to serial memory.[12]

The machine was programmed in pure machine code using an array of buttons and switches. Output consisted of a row of lights.

Internally, the Kenbak-1 has a serial computer architecture, processing one bit at a time.[15][16]

Technical description

Registers

| 07 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 02 | 01 | 00 | (bit position) |

| Main registers | ||||||||

| A | A | |||||||

| B | B | |||||||

| X | X (Index) | |||||||

| P | Program Counter | |||||||

| Flags | ||||||||

| 000000 | C | O | A flags | |||||

| 000000 | C | O | B flags | |||||

| 000000 | C | O | X flags | |||||

| Input/Output | ||||||||

| Output | Lights | |||||||

| Input | Switches | |||||||

The Kenbak-1 has a total of nine registers. All are memory mapped. It has three general-purpose registers: A, B and X. Register A is the implicit destination of some operations. Register X is also known as the index register and turns the direct and indirect modes into indexed direct and indexed indirect modes. It also has program counter, called Register P, three "overflow and carry" registers for A, B and X, respectively, as well as an Input Register and an Output Register.[17]

Addressing modes

Add, Subtract, Load, Store, Load Compliment, And, and Or instructions operate between a register and another operand using five addressing modes:

- Immediate (operand is in second byte of instruction)

- Memory (second byte of instruction is the address of the operand)

- Indirect (second byte of instruction is the address of the address of the operand)

- Indexed (second byte of instruction is added to X to form the address of the operand)

- Indirect Indexed (second byte of instruction points to a location which is added to X to form the address of the operand)

Instruction table

The instructions are encoded in 8 bits, with a possible second byte providing an immediate value or address. Some instructions have multiple possible encodings.[17]

| Opcode matrix for the Kenbak-1 instruction set | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High octal digits | Low octal digit | |||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||||||||||

| 00 | HALT | SFTR A1 | SET 0 b0 XXX | ADD A #XXX | ADD A XXX | ADD A (XXX) | ADD A XXX, X | ADD A (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 01 | HALT | SFTR A2 | SET 0 b1 XXX | SUB A #XXX | SUB A XXX | SUB A (XXX) | SUB A XXX, X | SUB A (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 02 | HALT | SFTR A3 | SET 0 b2 XXX | LOAD A #XXX | LOAD A XXX | LOAD A (XXX) | LOAD A XXX, X | LOAD A (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 03 | HALT | SFTR A4 | SET 0 b3 XXX | STORE A #XXX | STORE A XXX | STORE A (XXX) | STORE A XXX, X | STORE A (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 04 | HALT | SFTR B1 | SET 0 b4 XXX | JPD A ≠0 XXX | JPD A =0 XXX | JPD A <0 XXX | JPD A ≥0 XXX | JPD A >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 05 | HALT | SFTR B2 | SET 0 b5 XXX | JPI A ≠0 XXX | JPI A =0 XXX | JPI A <0 XXX | JPI A ≥0 XXX | JPI A >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 06 | HALT | SFTR B3 | SET 0 b6 XXX | JMD A ≠0 XXX | JMD A =0 XXX | JMD A <0 XXX | JMD A ≥0 XXX | JMD A >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 07 | HALT | SFTR B4 | SET 0 b7 XXX | JMI A ≠0 XXX | JMI A =0 XXX | JMI A <0 XXX | JMI A ≥0 | JMI A >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 10 | HALT | ROTR A1 | SET 1 b0 XXX | ADD B #XXX | ADD B XXX | ADD B (XXX) | ADD B XXX, X | ADD B (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 11 | HALT | ROTR A2 | SET 1 b1 XXX | SUB B #XXX | SUB B XXX | SUB B (XXX) | SUB B XXX. X | SUB B (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 12 | HALT | ROTR A3 | SET 1 b2 XXX | LOAD B #XXX | LOAD B XXX | LOAD B (XXX) | LOAD B XXX, X | LOAD B (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 13 | HALT | ROTR A4 | SET 1 b3 XXX | STORE B #XXX | STORE B XXX | STORE B (XXX) | STORE B XXX, X | STORE B (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 14 | HALT | ROTR B1 | SET 1 b4 XXX | JPD B ≠0 XXX | JPD B =0 XXX | JPD B <0 XXX | JPD B ≥0 XXX | JPD B >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 15 | HALT | ROTR B2 | SET 1 b5 XXX | JPI B ≠0 XXX | JPI B =0 XXX | JPI B <0 XXX | JPI B ≥0 XXX | JPI B >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 16 | HALT | ROTR B3 | SET 1 b6 XXX | JMD B ≠0 XXX | JMD B =0 XXX | JMD B <0 XXX | JMD B ≥0 XXX | JMD B >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 17 | HALT | ROTR B4 | SET 1 b7 XXX | JMI B ≠0 XXX | JMI B =0 XXX | JMI B <0 XXX | JMI B ≥0 XXX | JMI B >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 20 | NOOP | SFTL A1 | SKP 0 b0 XXX | ADD X #XXX | ADD X XXX | ADD X (XXX) | ADD X XXX, X | ADD X (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 21 | NOOP | SFTL A2 | SKP 0 b1 XXX | SUB X #XXX | SUB X XXX | SUB X (XXX) | SUB X XXX. X | SUB X (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 22 | NOOP | SFTL A3 | SKP 0 b2 XXX | LOAD X #XXX | LOAD X XXX | LOAD X (XXX) | LOAD X (XXX) | LOAD X (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 23 | NOOP | SFTL A4 | SKP 0 b3 XXX | STORE X #XXX | STORE X XXX | STORE X (XXX) | STORE X XXX, X | STORE X (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 24 | NOOP | SFTL B1 | SKP 0 b4 XXX | JPD X ≠0 XXX | JPD X =0 XXX | JPD X <0 XXX | JPD X ≥0 XXX, X | JPD X >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 25 | NOOP | SFTL B2 | SKP 0 b5 XXX | JPI X ≠0 XXX | JPI X =0 XXX | JPI X <0 XXX | JPI X ≥0 XXX | JPI X >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 26 | NOOP | SFTL B3 | SKP 0 b6 XXX | JMD X ≠0 XXX | JMD X =0 XXX | JMD X <0 XXX | JMD X ≥0 XXX | JMD X >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 27 | NOOP | SFTL B4 | SKP 0 b7 XXX | JMI X ≠0 XXX | JMI X =0 XXX | JMI X <0 XXX | JMI X ≥0 XXX | JMI X >0 XXX | ||||||||||

| 30 | NOOP | ROTL A1 | SKP 1 b0 XXX | OR #XXX | OR XXX | OR (XXX) | OR XXX, X | OR (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 31 | NOOP | ROTL A2 | SKP 1 b1 XXX | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||||

| 32 | NOOP | ROTL A3 | SKP 1 b2 XXX | AND #XXX | AND XXX | AND (XXX) | AND XXX, X | AND (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 33 | NOOP | ROTL A4 | SKP 1 b3 XXX | LNEG #XXX | LNEG XXX | LNEG (XXX) | LNEG XXX. X | LNEG (XXX), X | ||||||||||

| 34 | NOOP | ROTL B1 | SKP 1 b4 XXX | JPD UNC XXX | JPD UNC XXX | JPD UNC XXX | JPD UNC XXX | JPD UNC XXX | ||||||||||

| 35 | NOOP | ROTL B2 | SKP 1 b5 XXX | JPI UNC XXX | JPI UNC XXX | JPI UNC XXX | JPI UNC XXX | JPI UNC XXX | ||||||||||

| 36 | NOOP | ROTL B3 | SKP 1 b6 XXX | JMD UNC XXX | JMD UNC XXX | JMD UNC XXX | JMD UNC XXX | JMD UNC XXX | ||||||||||

| 37 | NOOP | ROTL B4 | SKP 1 b7 XXX | JMI UNC XXX | JMI UNC XXX | JMI UNC XXX | JMI UNC XXX | JMI UNC XXX | ||||||||||

See also

- Datapoint 2200, a contemporary machine with alphanumeric screen and keyboard, suitable to run non-trivial application programs

- Mark-8, designed by graduate student Jonathan A. Titus and announced as a "loose kit" in the July 1974 issue of Radio-Electronics magazine

- Altair 8800, a very popular 1975 microcomputer that provided the inspiration for starting Microsoft

- Gigatron TTL, a 21st-century implementation of a computer using small-scale integration parts

References

- 1 2 "Oral History of John Blankenbaker" (PDF). Computer History Museum. June 14, 2007.

- ↑ "What was the First PC?". Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ "PastExibits LINK - History of the PC". Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ↑ "The George R. Stibitz Computer Pioneer Award". Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ↑ "Timeline of Computer History". Computer History Museum. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ BBC News, November 6, 2015

- ↑ "Kenbak-1 The Training Computer". Computerworld. November 17, 1971. p. 43. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ↑ "List of Extant Kenbak-1 Computers". Kenbak.com. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ "Kenbak-1". Computer Museum of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ↑ p. 52, "The First Personal Computer", Popular Mechanics, January 2000.

- ↑ Robert R Nielsen, Snr (2005). "Inside the Kenbak-1". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 Erik Klein. "Kenbak Computer Company Kenbak-1". Old-computers.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ↑ Bill Wilson (6 November 2015). "The man who made 'the world's first personal computer'". BBC News.

- ↑ "Technical".

- ↑ "Kenbak Theory of Operation Manual". p. 16.

- ↑ "Official Kenbak-1 Reproduction Kit".

- 1 2 "Programming Reference Manual KENBAK-l Computer"

External links

- Kenbak.com Comprehensive Kenbak-1 history and technical information

- KENBAK-1 Computer Article

- KENBAK-1 Computer – Official Kenbak-1 website at www.kenbak-1.info

- Kenbak-1 Emulator – Kenbak-1 Emulator download

- Kenbak 1 – Images and information at www.vintage-computer.com

- Kenbak documentation at bitsavers.org