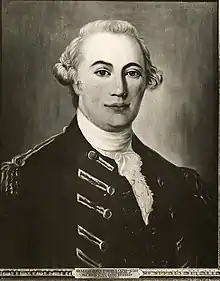

John Forbes | |

|---|---|

Brigadier General John Forbes 1707-1759 | |

| Born | 5 September 1707 Dunfermline, Scotland |

| Died | 11 March 1759 (aged 51) Philadelphia, British America |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1735–1759 |

| Rank | Brigadier-general |

| Unit | 17th Foot 1757-1759 |

| Battles/wars | War of the Austrian Succession Dettingen (1743) Fontenoy (1745) Lauffeld (1747) French and Indian War Louisbourg Expedition (1757) Fort Duquesne (1758) |

| Relations | Duncan Forbes, Lord President |

John Forbes (5 September 1707 – 11 March 1759) was a Scottish professional soldier who served in the British Army from 1729 until his death in 1759.

During the 1754 to 1763 French and Indian War, he commanded the 1758 Forbes Expedition that occupied the French outpost of Fort Duquesne, now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This required the construction of a military trail known as the Forbes Road, which became an important route for settlement of the Western United States.

Forbes died in Philadelphia and was buried in the chancel of Christ Church.

Life

John Forbes was born in Dunfermline on 5 September 1707, youngest child of Colonel John Forbes, 1658–1707, who died several months before his birth, and Elizabeth Graham, daughter of an Edinburgh merchant. His uncle, Duncan Forbes (1644-1704), was a prominent supporter of William of Orange and obtained his brother John an army commission.[1]

In 1701, Colonel Forbes purchased Pittencrieff Park, near Dunfermline, and it was here John grew up. He had five elder sisters, of whom little is known, and two older brothers; Arthur (1703-1757), who inherited the estate, and Hugh (1704-1760), who became a lawyer.[2] All three of the Forbes brothers had problems with money; John borrowed large sums to pursue his military career, while Arthur ruined himself expanding Pittencrief, which was sold after his death.[3]

Forbes married Anna Donald and had a daughter Anna.

Career

%252C_by_follower_of_Jean-Baptiste_van_Loo.jpg.webp)

The Forbes family were prominent civic leaders in Inverness, who supported the succession of George I in 1714 and were political allies of the Campbell Dukes of Argyll. John's cousin Duncan Forbes of Culloden, (1685-1747), became senior Scottish legal officer in 1737 and played a key role in suppressing the 1745 Jacobite Rising. These personal connections were essential; like many contemporaries, John was also a Freemason, another of the informal networks needed for a successful public career in this period.[4]

Educated locally in Dunfermline, Forbes is thought to have studied medicine at Edinburgh University.[5] In September 1729, he was appointed surgeon in the Royal Scots Greys, [lower-alpha 1] then based in Scotland. He remained with the regiment for the next 28 years but gave up his medical post in 1735, when he was commissioned as a cornet.[6]

The long period of peace from 1713 to 1739 meant limited opportunities for promotion, while the commission purchase system worked against those like Forbes with little money.[lower-alpha 2] It was not until April 1742 he was promoted lieutenant, shortly before the regiment was posted to the Austrian Netherlands to fight in the War of the Austrian Succession.[7] Forbes became aide-de-camp to James Campbell of Lawers, (1690-1745), colonel of the Scots Greys and commander of the Allied cavalry. He fought at Dettingen in June 1743 and in September 1744, purchased a commission as captain.[8]

At Fontenoy in May 1745, Campbell sent Forbes with instructions to Brigadier General Ingoldsby on the Allied right, ordering him to attack a French redoubt whose fire was impeding their advance. One shot badly wounded Sir James, who was carried from the field; Forbes stayed with him after the Allies retreated and was taken prisoner. He was soon exchanged but Campbell died a few days later and Forbes' letters display genuine grief at his death.[9]

Many viewed Fontenoy as a 'defeat snatched from the jaws of victory', and in the recriminations that followed, Ingoldsby was court-martialled. The grounds were his failure to comply with three separate orders to attack the French position, given by Campbell, Cumberland, the Allied commander, and Ligonier. Ingoldsby claimed he received conflicting instructions and attempted to blame Forbes, who testified at his trial. While he had some justification, any confusion was caused by Cumberland, not Forbes; in any case, this was not considered an adequate excuse and Ingoldsby was forced to resign.[10]

For reasons that are unclear, unlike many who fought at Fontenoy Forbes did not benefit from Cumberland's patronage, although he was appointed aide to the elderly Earl of Stair, (1673-1747), Campbell's successor as colonel of the Scots Greys. Some units were sent to Britain in October to put down the 1745 Rising, but not the cavalry, since transporting horses by sea was considered impractical during the winter months. Stair was military commander of Southern Britain and Forbes may have served there for a short period but contrary to legend, he was not present at Culloden.[11] Instead, he returned to Flanders in December 1745 as Deputy Quartermaster-General and was a major when the war ended in 1748.[12]

Forbes spent the next few years on garrison duty in different parts of Britain and in November 1750, purchased a commission as Lieutenant-Colonel of the Scots Greys.[13] To do so, he borrowed £5,000 but with limited opportunities for further advancement, his debts became an increasingly large problem.[14]

The Forbes Expedition

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle set up a commission to resolve territorial disputes between British and French colonies in North America, including the Ohio Country, French Acadia and Nova Scotia. Neither side was willing to make concessions, which led to the 1754-1763 French and Indian War; in 1755, an expedition under General Braddock to capture Fort Duquesne ended in a disastrous defeat.[15]

When the global conflict known as the Seven Years' War began in 1756, James Campbell's nephew, the Earl of Loudoun, was appointed Commander-in-Chief, North America and Governor General of Virginia. In early 1757, Forbes was in Southern England, training a 'light company' of the Scots Greys for attacks on the French coast.[16] In March, he was promoted colonel of the 17th Foot, part of a force of 5,400 sent to Novia Scotia for an attempt on Louisbourg.[17]

Following the failure of the 1757 Louisbourg Expedition, Forbes was promoted Brigadier general in December 1757 and given command of another attack on Fort Duquesne. His force contained 1,400 regulars, 400 from the Royal American Regiment, commanded by the experienced Swiss mercenary, Lt-Colonel Henry Bouquet, along with 1,000 Scots who made up Montgomerie's Highlanders. There were also 5,000 provincial militia from Virginia and Pennsylvania, commanded by George Washington, who had carried messages to Fort Le Boeuf in 1753, and accompanied Braddock in 1755.[18]

Forbes decided to build a new road from the Pennsylvania frontier, since it required fewer river crossings than that used by Braddock, which followed a trail cut in 1752 by the Virginia-based Ohio Company. The decision led to protests from his Virginian officers, many of whom were investors in the company, including two of Washington's brothers.[19]

As a compromise, Forbes agreed to improve Braddock's original road, but use the route through Pennsylvania. A base was established at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and a trail cut through the Allegheny Mountains, which became the Forbes Road. Already severely ill, Forbes had to be carried in a litter and relied heavily on Bouquet, who commanded the advance guard. Construction of the road and bases such as Fort Ligonier was supervised by Lt-Colonel John St Clair, who proved to be incompetent and required Forbes to do much of the work, despite his poor health.[20]

A less appreciated aspect of Forbes' leadership was in building relationships with local Native Americans, who previously refused to co-operate with the British. These efforts were bolstered by the capture of Fort Frontenac in August, increasing British prestige, while the loss of French traders severely impacted the local economy.[21] This methodical approach was jeopardised by the Battle of Fort Duquesne, on 15 September 1758, when a column under Major James Grant advanced too far ahead of the main body and suffered over 300 casualties. Forbes decided to suspend operations but on 26 October, 13 Ohio Valley tribes signed the Treaty of Easton with Pennsylvania and New Jersey.[22]

After the loss of their local allies, the French abandoned Fort Duquesne and the British took possession on 25 November. Forbes ordered the construction of Fort Pitt, named after British Secretary of State Pitt the Elder. He also established a settlement between the rivers, the site of modern Pittsburgh.[23] His health rapidly declined during the campaign; described as a 'wasting disease', this is thought to have been stomach cancer, combined with severe dysentery.

On 3 December 1758, he left Colonel Hugh Mercer in command and returned to Philadelphia, where he died on 11 March 1759 and was buried with full military honours. His final correspondence with Lord Amherst, the new commander in North America, included the recommendation he make his relationship with Native Americans a priority and 'not to think lightly of them or their friendship.'[24] [lower-alpha 3]

Legacy

Forbes Field, now demolished but which formerly served as the home field for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Pittsburgh Steelers and the Pitt Panthers football team, was named after John Forbes. Forbes Field was America's first all-steel and concrete baseball stadium. Forbes Avenue, one of the city of Pittsburgh's principal boulevards, runs from the Monongahela river in Downtown Pittsburgh to Frick Park and the start of the eastern suburbs. It is named in his honor and roughly follows his colonial road.[25] John Forbes Lane in Kanpur running from British India Corporation to Huddard High School is named in his memory.

Footnotes

- ↑ Officially known as the 2nd Dragoons

- ↑ Ability to pay was one factor; length of service determined first right of refusal, while purchases had to be approved by senior officers

- ↑ During the Pontiac Rebellion in 1763, Fort Pitt suffered an outbreak of smallpox; Amherst and Bouquet discussed giving infected blankets to the local tribes

References

- ↑ Du Toit 2004, p. Online.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 3.

- ↑ "Pittencrieff House". Castles of Scotland. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 4.

- ↑ Waddell 2005, p. ANB Online.

- ↑ "Kensington, George R., et al., "George the Second..." Docketed: " John Forbes Surgeon for the Royal Regiment of North British Dragoons "". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ↑ Grant 1972, p. 9.

- ↑ "Peteghem, George Wade, et al., "George Wade Esqr. Field Marshal..." 1744 September 24"". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Skrine 1906, pp. 233.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 56.

- ↑ "Court at St. James's, George R, et al., "George the Second..." Docketed: " John Forbes, Esqr: Major to the Royal Regiment of North British Dragoons "". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ↑ "Court at St. James's, George R. "George the Second..." Docketed: " John Forbes, Esqr: Lieutenant Colonel to the Earl of Rothes's Regiment of North British Dragoons " 1750 November 29". University of Virginia. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 71.

- ↑ Royle 2016, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 76.

- ↑ Oliphant 2015, p. 81.

- ↑ Royle 2016, p. 205.

- ↑ Toner 1897, p. 190.

- ↑ Cubbison 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Royle 2016, p. 206.

- ↑ Royle 2016, p. 207.

- ↑ Lorant 1999, p. 103.

- ↑ Royle 2016, p. 208.

- ↑ Gershman, Michael (1993). Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-61212-8..

Sources

- Cubbison, Douglas (2010). The British Defeat of the French in Pennsylvania, 1758: A Military History of the Forbes Campaign Against Fort Duquesne. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786447398.

- Du Toit, Alexandre (2004). "Forbes, Duncan (b. in or after 1643, d. 1704)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9821. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Grant, Charles (1972). Royal Scots Greys (Men-at-Arms). illustrated by Michael Youens. Osprey. ISBN 978-0850450590.

- Lloyd, EM (2004). "Forbes, John (1707-1759)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9837. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lorant, Stefan (1999). Pittsburgh, The Story of an American City. Larsen's Outdoor Publishing. ISBN 978-0967410302.

- Oliphant, John (2015). John Forbes: Scotland, Flanders and the Seven Years' War, 1707-1759. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1472511188.

- Royle, Trevor (2016). Culloden; Scotland's Last Battle and the Forging of the British Empire. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408704011.

- Skrine, Francis Henry (1906). Fontenoy and Great Britain's Share in the War of the Austrian Succession 1741–48 (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-0260413550.

- Charles M. Stotz, Outposts of the War for Empire: The French and English in Western Pennsylvania: Their Armies, Their Forts, Their People, 1749-1764 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985).

- Toner, JM (1897). "Washington in the Forbes Expedition of 1758". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 1: 185–213. JSTOR 40066707.</ref>

- Waddell, Louis M (2005). Forbes, John (1707-1759) (Online ed.). ANB Online. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0100293.

- Louis M. Waddell and Bruce D. Bomberger, The French and Indian War in Pennsylvania:Fortification and Struggle During the War for Empire (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1996).

External links

- "John Forbes 1707-1759". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Kensington, George R., et al., "George the Second..." Docketed: " John Forbes Surgeon for the Royal Regiment of North British Dragoons "". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Court at St. James's, George R, et al., "George the Second..." Docketed: " John Forbes, Esqr:, Deputy Quarter Master General" 1745 December 24". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Pittencrieff House". Castles of Scotland. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online