Juan Álvarez | |

|---|---|

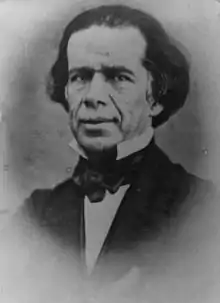

Portrait made by an unknown artist, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Historia | |

| 24th President of Mexico | |

| In office 4 October – 11 December 1855 | |

| Preceded by | Rómulo Díaz de la Vega |

| Succeeded by | Ignacio Comonfort |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 January 1790 Atoyac, New Spain |

| Died | 21 August 1867 (aged 77) La Providencia, Guerrero |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Liberal |

Juan Nepomuceno Álvarez Hurtado de Luna, generally known as Juan Álvarez, (27 January 1790 – 21 August 1867) was a general, long-time caudillo (regional leader) in southern Mexico, and president of Mexico for two months in 1855, following the liberals' ouster of Antonio López de Santa Anna. His presidency inaugurated the pivotal era of La Reforma.

Álvarez had risen to power in the Tierra Caliente, in southern Mexico with the support of indigenous peasants whose lands he protected. He fought along with heroes of the insurgency, José María Morelos and Vicente Guerrero in the War of Independence and went on to fight in all the major wars of his day, from the "Pastry War", to the Mexican–American War, and the War of the Reform to the war against the Second French Intervention. A liberal reformer, a republican and a federalist, he was the leader of a revolution in support of the Plan de Ayutla in 1854, which led to the deposition of Santa Anna from power and the beginning of the political era in Mexico's history known as the Liberal Reform. According to historian Peter Guardino: "Álvarez was most important as a champion of the incorporation of Mexico's peasant masses into the polity of [Mexico] ... advocating universal male suffrage and municipal autonomy."[1]

Early life

Juan Álvarez was born in the town of Santa Maria de la Concepcion Atoyac on 27 January 1790. His parents were Antonio Álvarez from Santiago Galicia and Rafaela Hurtado from Acapulco. He was educated in Mexico City under the direction of Ignacio Aviles, whom Álvarez later entrusted the education of his first son with.

He took part in the Mexican War of Independence when it first broke out in 1810, joining the forces of José María Morelos as part of the second battalion of the Guadalupe Regiment on 17 November 1810, and being promoted to sergeant the following month. He was promoted to colonel less than a year afterward. One of the first important tasks entrusted to him by Morelos was making a trip to Zacatula amidst great risk. He gained Morelos' trust enough to be a part of his personal escort, and on 11 January took part in the rout of the Spanish General Francisco Paris.[2]

He was the head of the company sent by Morelos to accept the surrender of the Fort of San Diego, during which he became a victim of perfidy as the Spanish commander of the fort allowed Álvarez' forces to get close to the fort before firing upon them. Most of Álvarez' men died and Álvarez himself was injured in both legs, but was saved by the soldier Diego Eugenio Salas who carried him to safety despite being injured himself.[3]

Amidst the fighting he lost his home and his wealth which amounted to thirty-five pesos, and he had to live off of the land, but he kept the fight against the Spaniards and earned the nom du guerre Gallego. In 1821, he joined the Agustin de Iturbide's Trigarantine Army, and led a siege of Acapulco with three hundred men until finally taking possession of the port on 15 October. After independence was won, he asked the government for permission to retire but it was denied, and instead was tasked with commanding the Acapulco fortress.

First Mexican Republic

At the end of 1822 when Vicente Guerrero and Nicolás Bravo proclaimed against the First Mexican Empire, Álvarez joined them, and upon the adoption of the Constitution of 1824, he joined the moderate republican party. He was opposed to the Plan of Jalapa which sought to overthrow president Vicente Guerrero, and fought for him, though President Guerrero was eventually overthrown.[4]

He fought against the conservative revolt against the liberal administration of Valentín Gómez Farías in May, 1833, and once Gómez Farías had been overthrown by Santa Anna, Álvarez raised up the south against him, but his movement failed and he was sentenced to be banished, a sentence that was later commuted for peacefully diffusing another revolt in Acapulco.[5]

Centralist Republic of Mexico

He offered his services to the government against the French during the Pastry War of 1838, and having taken part in the revolt against Anastasio Bustamante in 1841, the triumphant Santa Anna promoted Álvarez to division general. He suppressed Indian uprisings in the mountains of Chilapa and the Tierra Caliente, insurgencies which tended to take on the characteristics of ethnic conflicts.[6]

He fought in the Mexican-American War though he played no notable role. During the conflict he was made commandant general of Puebla and harassed the American occupiers. He contributed to the establishment of the State of Guerrero in the south of the country and was its first governor. He fought against the Plan of Jalisco which overthrew President Mariano Arista and paved the way for the return of Santa Anna in 1853.

Plan of Ayutla

Álvarez was opposed to Santa Anna's subsequent dictatorship and on 20 February 1854, proclaimed a revolt against the government.[7] The dissident colonel Florencio Villareal on 1 March, proclaimed a revolutionary program in the town of Ayutla, Guerrero. A preamble set forth grievances against the dictatorship, and was followed by nine articles. 1. Santa Anna and his officers were stripped of authority in the name of the people. 2. After a majority of the nation had accepted the plan the revolutionary commander in chief was to convoke an assembly of representatives from each state and territory to choose an interim government. 3. The interim president was granted sufficient authority to carry out the tasks of government and protect national sovereignty. 4. The states who accepted the plan were to form new government while the indissolubility of the republic as a whole was emphasized. 5. The interim president was to convoke a congress. 6. Trade and military affairs were to be adequately administered. 7. Conscription and passport laws were to be abolished. 8. Opponents of the plan were to be treated as threats to national independence. 9. Placed at the head of the movement Nicolas Bravo, Tomas Moreno and Juan Álvarez.[8] The plan was ratified at Acapulco with a few amendments, including a provision allowing changes to be made in accordance with the national will, and Álvarez was chosen as head of the movement.[9]

Santa Anna took fierce measures against the insurgency including the confiscation of property belonging to the revolutionists, the burning of hostile towns, and the execution of revolutionary commanders taken in arms.[10] Santa Anna personally led his troops against Acapulco but failed to take the city, and was forced to retreat back to Mexico City.[11] He continued the struggle, but the revolution continued to spread and by August, 1855 Santa Anna abdicated. His successor at the capital, Martín Carrera attempted to be a compromise candidate and began carrying out clauses of the Ayutla Plan, but Álvarez and the rest of the leaders did not trust him, viewing him as holdover from the Santa Anna regime, and an effort to dilute or coopt the revolution. After a month of failing to come to any agreement, Carrera resigned and the administrative responsibilities of government were handed over to the commander of the Mexico City garrison Rómulo Díaz de la Vega who supported the Plan of Ayutla, and awaited the arrival of Juan Álvarez.

Álvarez and his army reached Chilpancingo on 8 September 1855. Meanwhile, his lieutenant Ignacio Comonfort was at Lagos attempted to convince other, independent revolutionary leaders to recognize the leadership of Álvarez. This was achieved, and Álvarez continued his march towards Iguala intending to stay some time in Cuernavaca. At Iguala on 24 September 1855, in accordance with Article 2 of the Aytula Plan, he issued a decree appointing one representative from each state and territory and summoned them to assemble at Cuernavaca on 4 October to elect an interim president. The representatives assembled accordingly with ex liberal president Valentín Gómez Farías as the assembly president, and future president of Mexico Benito Juárez as one of the secretaries. On the same day they elected Álvarez to the position of president.[12]

Presidency

The president proceeded to form a cabinet and chose one of the commanders during the Aytula Plan, Ignacio Comonfort as Minister of War. Melchor Ocampo was made Minister of Relations, Guillermo Prieto was made Minister of the Treasury, and Benito Juarez of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs. Miguel Lerdo de Tejada was made Minister of Development.[13]

The first measure of the administration was the framing of an organic statue to serve as an interim constitution. Álvarez needed to strengthen the powers of the federal government and alleviate Mexico's chronic financial crisis. The president decreed that in the event of a vacancy in the executive office it ought to be filled by the council of state. On 15 October he also granted an amnesty to all military deserters, of which there had been many due to Santa Anna's conscription measures.[14] On 16 October, a call was made for a congress to assemble at Dolores Hidalgo in February 1856, to organize the nation under the republican, democratic, and representative form, based upon a decree dating back to the Bases of Tacubaya in 1841. The congress would eventually meet on schedule though Álvarez would have stepped down from the presidency before then.[15]

Due to the disorders which had flowed from militarism throughout Mexican history, the idea began to be floated in the cabinet of dissolving the military and starting over, Ocampo and Juarez being in favor while Comonfort being against wishing instead to reform the military class but not destroy it. This was just one example of the divisions that existed within the cabinet and Comonfort was publicly perceived as being more moderate than the rest of his fellow ministers.[16] Continuing clashes within the cabinet led to the resignation of the radical Ocampo in 7 December, and his office was handed over to Miguel Maria Arrioja.[17]

Meanwhile, there was a constitutional disorder throughout the republic. The new local governments which had been created by Article 4 of the Aytula Plan were now assuming virtual complete sovereignty over their territories, and the federal government took strict measures against this trend, forbidding the military governors, the commandant generals from interfering in treasury matters or seizing the funds of custom houses.[18] Álvarez, who had meanwhile been governing from Cuernavaca now moved himself and his troops to Mexico City. The alleged brutality of his troops known as 'pintos' (the mottled ones), caused distrust and alarm, and led to rumors that Álvarez was going to be overthrown in favor of Comonfort.[19]

Inauguration of La Reforma

Álvarez' cabinet which had included the progressive state governors Benito Juarez and Melchor Ocampo, and the poet Guillermo Prieto represented a new generation of liberals that had grown up since independence, and intended to pass unprecedented reforms during a period which began with the Álvarez administration and would eventually come to be known as La Reforma. The reforms would culminate in the Constitution of 1857, and open conflict with the opponents of the measures which would not entirely end until 1867.

They began with the Ley Juarez, which stripped the Mexican clergy of their independent legal privileges (fueros) which they had hereunto enjoyed under canon and civil law. The Ley Juarez was prefaced by the cause celebre of Father Javier Miranda. On 20 November 1855, the former conservative minister, Father Miranda was arrested in his home at Puebla. He was then transported to Mexico City where he was held at the barracks of San Hipolito.[20] This was technically illegal as the government could not at the time imprison a priest without collaboration from church authorities. The conservative press was outraged, and even the liberal press criticized the arrest as arbitrary and advocated for Miranda to be tried and for the government to explain its motives in arresting him.[21] The bishop of Puebla protested to the government, but to no avail. The only response of the government was to transport Miranda to the fortress of San Juan de Ullua in Veracruz Harbor. It was suspected that the arrest was due to Miranda's political views.[22]

The Ley Juarez was passed on 22 November 1855. Ecclesiastical tribunals were stripped of their ability to judge civil law cases. They were allowed to continue judging clergy in the cases of canon law.[23] With Father Miranda's case in mind, conservatives accused this measure as a means of passing severe anti-clerical laws, arresting priests on the slightest pretext, and then judging them in civil courts.[24] Opponents of the measure accused government deputies of hypocrisy for claiming to support equality before the law while maintaining their own immunity.[25]

The Archbishop protested against the measure and suggested that the question of the ecclesiastical fuero should be submitted to the pope, a suggestion which was rejected by the government. The conservative generals Santa Anna and Blanco were officially stripped of their charges and the liberals Degollado and Moreno were commissioned as generals. Comonfort was now threatening to resign and only keep the office of general in chief. Álvarez directed his secretaries to lay before him proposals on how to proceed, he also directed his council to prepare a draft of the organic statute. Meanwhile, the conservatives began to favor the moderate Comonfort for the presidency.[26]

Resignation

Álvarez seriously considered stepping down from the presidency and handing it over to Comonfort, but the latter's enemies urged Álvarez to stay in office. On 4 December, Álvarez summoned a meeting of the most prominent members of the liberal party for advice on how to proceed. He wavered on the matter and on the following day accepted the resignation of his entire ministry and summoned Luis de la Rosa in organizing another. The portfolios would remain empty for the rest of Álvarez' presidency.[27]

In Guanajuato, Manuel Doblado pronounced against the government of Juan Álvarez on 6 December, holding up the moderate Ignacio Comonfort as the new president. His proclamation accused Álvarez of attacking religion, the one thing that bound Mexicans together.[28] This would prove to be redundant, as before news of the revolt even reached the capital, the elderly President Álvarez who was not enjoying administrative tasks or the climate of Mexico City, decided to step down, and he announced as such on 8 December.[29] Álvarez met with Comonfort and officially transferred the presidency to him on 11 December.[30]

Later life

Álvarez left the capital on 18 December, with a military escort and headed to Guerrero where he fought against uprisings opposed to the Comonfort administration. He continued to fight for the liberal cause during the Reform War having the southern states as his base of operations. During the Second French intervention which began in 1861, he counseled President Juarez to keep the struggle alive, and Juarez gave orders for his Eastern forces to obey Álvarez in case they lost contact with the central government. He lived long enough to see the retreat of the French in 1866 and the fall of the Second Mexican Empire in June 1867. Álvarez died the same year on 21 August.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ Peter Guardino, "Juan Álvarez" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 73. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 477.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 478.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 478.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 478.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 478.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 647.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 648–649.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 648–649.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 651.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 652.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 665.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 667.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 667.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 668.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 667.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 669.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 669.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 669.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 119.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 120.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 120.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 127.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 127.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 128.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 671.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 672.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 130.

- ↑ Zamacois, Niceto (1881). Historia de Mexico Tomo XIV (in Spanish). JF Parres. p. 132.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. p. 673.

- ↑ Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 484.

Further reading

- Bushnell, Clyde G. "The Military and Political Career of Juan Álvarez, 1790-1867". PhD dissertation, University of Texas 1958.

- Guardino, Peter. "Juan Álvarez" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, p. 73. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- (in Spanish) De la Cueva, Mariano, ed. et al., Plan de Ayutla. Mexico 1954.

- (in Spanish) Díaz Díaz, Fernando. Caudillos y caciques: Antonio López de Santa Anna y Juan Álvarez. 1952.

- (in Spanish) García Puron, Manuel (1984). México y sus gobernantes, Vol. 2. Mexico City: Joaquín Porrúa.

- (in Spanish) Muñoz y Pérez, Daniel. El general don Juan Álvarez. 1959.

- (in Spanish) Orozco Linares, Fernando (1985). Gobernantes de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial. ISBN 968-38-0260-5.

External links

- Biographical details at Letras Libres (in Spanish).

.png.webp)