| Judeo-Tunisian Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Beit Shemesh, Jerusalem District, Israel[1] Houmt Souk, Djerba, Tunisia[2] Tunis, Tunisia[3] Gabes, Tunisia[4] |

Native speakers | 11,000 (2011–2018)[5] |

| Arabic script[1] Hebrew alphabet[1][6] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ajt (retired); subsumed in aeb (Tunisian Arabic) |

| Glottolog | jude1263 |

| ELP | Judeo-Tunisian Arabic |

Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, also known as Judeo-Tunisian, is a variety of Tunisian Arabic mainly spoken by Jews living or formerly living in Tunisia.[6] Speakers are older adults, and the younger generation has only a passive knowledge of the language.[1]

The vast majority of Tunisian Jews have relocated to Israel and have shifted to Hebrew as their home language.[3][7] Those in France typically use French as their primary language, while the few still left in Tunisia tend to use either French or Tunisian Arabic in their everyday lives.[3][7]

Judeo-Tunisian Arabic is one of the Judeo-Arabic languages, a collection of Arabic dialects spoken by Jews living or formerly living in the Arab world.[6]

History

Before 1901

A Jewish community existed in what is today Tunisia even prior to Roman rule in Africa.[8] After the Arabic conquest of North Africa, this community began to use Arabic for their daily communication.[3] They had adopted the pre-Hilalian dialect of Tunisian Arabic as their own dialect.[3] As Jewish communities tend to be close-knit and isolated from the other ethnic and religious communities of their countries,[6] their dialect spread to their coreligionists all over the country[2][9] and had not been in contact with the languages of the communities that invaded Tunisia in the middle age.[3][10] The primary language contact with regard to Judeo-Tunisian Arabic came from the languages of Jewish communities that fled to Tunisia as a result of persecution like Judeo-Spanish.[8] This explains why Judeo-Tunisian Arabic lacks influence from the dialects of the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, and has developed several phonological and lexical particularities that distinguish it from Tunisian Arabic.[10][11][12] This also explains why Judeo-Tunisian words are generally less removed from their etymological origin than Tunisian words.[13]

The most famous author in Judeo-Arabic is Nissim B. Ya‘aqov b. Nissim ibn Shahin of Kairouan (990-1062). An influential rabbinical personality of his time, Nissim of Kairouan wrote a collection of folks stories intended for moral encouragement, at the request of his father-in-law on the loss of his son. Nissim wrote "An Elegant Compilation concerning Relief after Adversity" (Al-Faraj ba‘d al-shidda)[14] first in an elevated Judeo-Arabic style following Sa‘adia Gaon's coding and spelling conventions and later translated the work into Hebrew.[15]

The first Judeo-Arabic printing house opens in Tunis in 1860. A year after, the 1856 Fundamental Pact is translated and printed in Judeo-Arabic (in 1861[16] before its translation into Hebrew in 1862).

After 1901

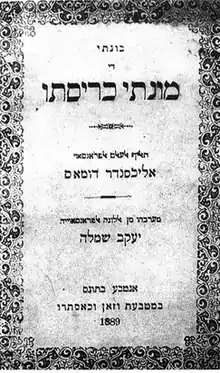

In 1901, Judeo-Tunisian became one of the main spoken Arabic dialects of Tunisia, with thousands of speakers.[8] Linguists noted the unique character of this dialect, and subjected it to study.[8] Among the people studying Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, Daniel Hagege[17] listed a significant amount of Judeo-Tunisian Arabic newspapers from the early 1900s in his essay The Circulation of Tunisian Judeo-Arabic Books.[18] in 1903, David Aydan prints in Judeo-Arabic "Vidu-i bel arbi", a translation of the ritual text recited by the community on Yom Kippur's eve. The text is printed in Djerba, a significant point to mention as many works published by the Tunisian Jewish community in Hebrew are printed in Livorno, Italy.[19] Educated leaders within the Tunisian Jewish community like ceramic merchant Jacob Chemla translated several works into Judeo-Tunisian, including The Count of Monte Cristo.

However, its emergence has significantly declined since 1948 due to the creation of Israel.[8] In fact, the Jewish community of Tunisia has either chosen to leave or was forced to leave Tunisia and immigrate to France or Israel.[3][7] Nowadays, the language is largely extinct throughout most of Tunisia, even if it is still used by the small Jewish communities in Tunis, Gabes and Djerba,[2][3][4] and most of the Jewish communities that have left Tunisia have chosen to change their language of communication to the main language of their current country.[3]

Current situation

Language vitality: Judeo-Tunisian Arabic is believed to be vulnerable with only 500 speakers in Tunisia[20] and with about 45,000 speakers in Israel[21]

Language variations: In Tunisia, geography plays a huge role in how Judeo-Tunisian Arabic varies between speakers.[22] In fact, Tunisian Judeo-Arabic can vary depending on the region in which it is spoken.[22] Accordingly, the main dialects of Judeo-Tunisian Arabic are:[22]

- The dialect of the North of Tunisia (Mainly spoken in Tunis)

- The dialect of the South of Tunisia (Mainly Spoken in Gabes)

- The dialect of the islands off the coast of the country (Mainly spoken in Djerba)

In addition, Judeo-Tunisian can vary within the same region based on the town in which it is spoken.[22]

Distinctives from Tunisian Arabic

Like all other Judeo-Arabic languages, Judeo-Tunisian Arabic does not seem to be very different from the Arabic dialect from which it derives, Tunisian Arabic.[3][6][23][24][25]

- Phonology: There are three main differences between Tunisian Arabic phonology and Judeo-Tunisian Arabic phonology:

- Substitution of phonemes: Unlike most dialects of Tunisian Arabic, Judeo-Tunisian Arabic has merged Tunisian Arabic's glottal [ʔ] and [h] into [∅],[3][8] Interdental [ð] and [θ] have respectively been merged with [d] and [t],[3][8] Ḍah and Ḍād have been merged as [dˤ] and not as [ðˤ],[3][8] Prehilalian /aw/ and /ay/ diphthongs have been kept[3][8] (except in Gabes[26]), and [χ] and [ʁ] have been respectively substituted by [x] and [ɣ].[3][8] This is mainly explained by the difference between the language contact submitted by Jewish communities in Tunisia and the one submitted by other Tunisian people.[8]

- Sibilant conversion:

- [ʃ] and [ʒ] are realized as [sˤ] and [zˤ] if there is an emphatic consonant or [q] later in the word (however in Gabes this change takes effect if [ʃ] and [ʒ] are either before or after an emphatic consonant or [q]).[4] For example, راجل rājil (meaning man) is pronounced in Gabes dialect of Judeo-Tunisian Arabic as /rˤa:zˤel/ and حجرة ḥajra (meaning stone) is pronounced in all Judeo-Tunisian dialects as /ħazˤrˤa/.[4]

- [ʃ] and [ʒ] are realized as [s] and [z] if there is an [r] later in the word (Not applicable to the dialect of Gabes).[4] For example, جربة jirba (meaning Djerba) is pronounced in all Judeo-Tunisian dialects except the one of Gabes as /zerba/.[4]

- Chibilant conversion: Unlike in the other Judeo-Arabic languages of the Maghreb,[27] [sˤ], [s] and [z] are realized as [ʃ], [ʃ] and [ʒ] in several situations.[4]

- [sˤ] is realized as [ʃ] if there is not another emphatic consonant or a [q] within the word (only applicable to Gabes dialect) or if this [sˤ] is directly followed by a [d].[26] For example, صدر ṣdir (meaning chest) is pronounced as /ʃder/[26] and صف ṣaff (meaning queue) is pronounced in Gabes dialect of Judeo-Tunisian Arabic as /ʃaff/.

- [s] and [z] are respectively realized as [ʃ] and [ʒ] if there is no emphatic consonant, no [q] and no [r] later in the word (In Gabes, this change takes effect if there is no [q] and no emphatic consonant within the word). For example, زبدة zibda (meaning butter) is pronounced as /ʒebda/.[4]

- Emphasis of [s] and [z]: Further than the possible conversion of [s] and [z] by [sˤ] and [zˤ] due to the phenomenon of the assimilation of adjacent consonants (also existing in Tunisian Arabic),[23] [s] and [z] are also realized as [sˤ] and [zˤ] if there is an emphatic consonant or [q] later in the word (however in Gabes this change takes effect if [ʃ] and [ʒ] are either before or after an emphatic consonant or [q]).[4] For example, سوق sūq (meaning market) is pronounced in Judeo-Tunisian Arabic as /sˤu:q/.[4]

- [q] and [g] phonemes: Unlike the Northwestern, Southeastern and Southwestern dialects of Tunisian Arabic, Judeo-Tunisian Arabic does not systematically substitute Classical Arabic [q] by [g].[27] Also, the [g] phoneme existing in Tunis, Sahil and Sfax dialects of Tunisian Arabic is rarely maintained[28] and is mostly substituted by a [q] in Judeo-Tunisian.[3] For example, بقرة (cow) is pronounced as /bagra/ in Tunis, Sahil and Sfax dialects of Tunisian Arabic and as /baqra/ in Judeo-Tunisian.[3]

- Morphology: The morphology is quite the same as the one of Tunisian Arabic.[3][6][23] However:

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic sometimes uses some particular morphological structures such as typical clitics like qa- that is used to denote the progressivity of a given action.[3][29] For example, qayākil means he is eating.

- Unlike Tunisian Arabic, Judeo-Tunisian Arabic is characterized by its extensive use of the passive form.[3][10]

- The informal lack of subject-verb agreement found in Tunisian and in Modern Standard Arabic does not exist in Judeo-Tunisian Arabic. For example, we say ed-dyār tebnēu الديار تبناوا and not ed-dyār tebnēt الديار تبنات (The houses were built).[30]

- Vocabulary: There are some differences between the vocabulary of Tunisian Arabic and the one of Judeo-Tunisian Arabic. Effectively:

- Unlike Tunisian Arabic, Judeo-Tunisian Arabic has a Hebrew adstratum.[2][6][31] In fact, Cohen said that almost 5 percent of the Judeo-Tunisian words are from Hebrew origin.[27] Furthermore, Judeo-Tunisian has acquired several specific words that do not exist in Tunisian like Ladino from language contact with Judaeo-Romance languages.[27][32]

- Unlike most of the Tunisian Arabic dialect and as it is Pre-Hilalian, Judeo-Tunisian kept Pre-Hilalian vocabulary usage patterns.[33] For example, rā را is used instead of šūf شوف (commonly used in Tunisian) to mean "to see".[33]

- Unlike the Tunis dialect of Tunisian Arabic,[11] Judeo-Tunisian Arabic is also known for the profusion of diminutives.[11] For example:

References

- 1 2 3 4 Raymond G. Gordon Jr., ed. 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 15th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- 1 2 3 4 (in Hebrew) Henschke, J. (1991). Hebrew elements in the Spoken Arabic of Djerba. Massorot, 5-6, 77-118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 (in French) Cohen, D. (1975). Le parler arabe des Juifs de Tunis: Étude linguistique. La Haye: Mouton.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sumikazu, Yoda. ""Sifflant" and "Chuintant" in the Arabic Dialect of the Jews of Gabes (south Tunisia)". Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik. 46: 21. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Judeo-Tunisian Arabic at Ethnologue (23rd ed., 2020)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (in French) Bar-Asher, M. (1996). La recherche sur les parlers judéo-arabes modernes du Maghreb: état de la question. Histoire épistémologie langage, 18(1), 167-177.

- 1 2 3 Bassiouney, R. (2009). Arabic sociolinguistics. Edinburgh University Press, pp. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Leddy-Cecere, T. A. (2010). Contact, Restructuring, and Decreolization: The Case of Tunisian Arabic. University of Pennsylvania, pp. 47-71.

- ↑ (in French) Saada, L. (1956). Introduction à l'étude du parler arabe des juifs de Sousse.

- 1 2 3 (in French) Vanhove, M. (1998). De quelques traits préhilaliens en maltais. Peuplement et Arabisation au Maghreb Occidental (Dialectologie et Histoire), 97-108.

- 1 2 3 4 5 (in French) Cohen, D. (1970). Les deux parlers arabes de Tunis. Notes de phonologie comparee. In his Etudes de linguistique semitique et arabe, 150(7).

- ↑ (in French) Caubet, D. (2000). Questionnaire de dialectologie du Maghreb (d'après les travaux de W. Marçais, M. Cohen, GS Colin, J. Cantineau, D. Cohen, Ph. Marçais, S. Lévy, etc.). Estudios de dialectología norteafricana y andalusí, EDNA, (5), 73-90.

- ↑ Aslanov, C. (2016). Remnants of Maghrebi Judeo-Arabic among French-born Jews of North-African Descent. Journal of Jewish Languages, 4(1), 69-84.

- ↑ Schippers, A (2012). "Stories about women in the collections of Nissim ibn Shāhīn, Petrus Alphonsi, and Yosef ibn Zabāra, and their relation to medieval European narratives - Frankfurter Judaistische Beiträge" (PDF). pure.uva.nl.

- ↑ Tobi, Yosef Yuval (2007). "L'ouverture de la littérature judéo-arabe tunisienne à la littérature arabo-musulmane - in "Entre orient et occident" p 255-275". www.cairn.info.

- ↑ Fontaine, Jean (1999). Histoire de la littérature tunisienne du XIII siècle à l'indépendance. Chap XXième siècle, textes en judéo-arabe et hébreu. Tunis, Tunisia: Cérès Editions. p. 229. ISBN 9973-19-404-7.

- ↑ Malul, Chen (7 September 2020). "The Story of Daniel Hagège: Judeo-Arabic Author and Documenter of Tunisian Jewry". blog.nli.org.il/.

- ↑ Tobi, Joseph (2014). Judeo-Arabic Literature In Tunisia, 1850-1950. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. pp. 241–320. ISBN 978-0-8143-2871-2.

- ↑ Fontaine, Jean (1999). Histoire de la littérature tunisienne du XIIIième siècle à l'indépendance. Chap XXième siècle, textes en judéo-arabe et en hébreu. Tunis, Tunisia: Cérès Editions. p. 230. ISBN 9973-19-404-7.

- ↑ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". Unesco.org. UNESCO. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Arabic, Judeo-Tunisian". Ethologue Languages of the World. Ethnologue. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Henshke, Yehudit (2010). "Different Hebrew Traditions: Mapping Regional Distinctions in the Hebrew Component of Spoken Tunisian Judeo-Arabic". Studies in the History and Culture of North African Jewry: 109. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Talmoudi, Fathi (1979) The Arabic Dialect of Sûsa (Tunisia). Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- ↑ Hammet, Sandra (2014). "Irregular verbs in Maltese and Their Counterparts in The Tunisian and Moroccan Dialects" (PDF). Romano-Arabica. 14: 193–210. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Arevalo, Tania Marica Garcia (2014). "The General Linguistic Features of Modern Judeo-Arabic Dialects in the Maghreb". Zutot. 11: 54–56. doi:10.1163/18750214-12341266.

- 1 2 3 Sumikazu, Yoda. ""Sifflant" and "Chuintant" in the Arabic Dialect of the Jews of Gabes (south Tunisia)". Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik. 46: 16. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Cohen, D. (1981). Remarques historiques et sociolinguistiques sur les parlers arabes des juifs maghrébins. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1981(30), 91-106.

- ↑ Cohen, D. (1973). Variantes, variétés dialectales et contacts linguistiques en domaine arabe. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris, 68(1), 233.

- ↑ Cuvalay, M. (1991). The expression of durativity in Arabic. The Arabist, Budapest studies in Arabic, 3-4, 146.

- ↑ (in French) Taieb, J., & Sayah, M. (2003). Remarques sur le parler judéo-arabe de Tunis. Diasporas Histoire et Sociétés, n° 2, Langues dépaysées. Presses Universitaires de Mirail, pp. 58.

- ↑ Chetrit, J. (2014). Judeo-Arabic Dialects in North Africa as Communal Languages: Lects, Polylects, and Sociolects. Journal of Jewish Languages, 2(2), 202-232.

- ↑ (in French) Dufour, Y. R. (1998). La langue parlée des Tunes. modia.org. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- 1 2 (in French) Cohen, D. (1962). Koinè, langues communes et dialectes arabes. Arabica, 9(2), 122.

Further reading

- Garcia Arévalo, T. M. (2014). The General Linguistic Features of Modern Judeo-Arabic Dialects in the Maghreb. Zutot, 11(1), 49–56. doi:10.1163/18750214-12341266.

- Bar-Asher, M., &. Fraade, S. D. (2010). Studies in the history and culture of North African Jewry. In Proceedings of the symposium at Yale. New Haven: Program in Judaic Studies, Yale.

- Sumikazu, Y., & Yoda, S. (2006). " Sifflant" and" chuintant" in the Arabic dialect of the Jews of Gabes (south Tunisia). Zeitschrift für arabische Linguistik, (46), 7-25.

- Tobi, Y., & Tobi, T. (2014). Judeo-Arabic Literature in Tunisia, 1850-1950. Detroit, MI: Wayne State UP. ISBN 978-0-8143-2871-2.

- Hammett, S. (2014). Irregular verbs in Maltese and their counterparts in the Tunisian and Morccan dialects. Romano-Arabica, 14, 193–210.

- (in French) Saada, L. (1969). Le parler arabe des Juifs de Sousse (Doctoral dissertation, PhD thesis, University of Paris).

- (in French) Cohen, D. (1975). Le parler arabe des Juifs de Tunis: Étude linguistique. La Haye: Mouton.

- (in French) Cohen, D. (1970). Les deux parlers arabes de Tunis. Études de linguistique sémitique et arabe, 150–171.

External links

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic in Endangered Languages Project

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic in Ethnologue

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic in Glottolog

- Judeo-Tunisian Arabic in Joshua Project