| Kangnido map (1402) | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 혼일강리역대국도지도 |

| Hanja | 混一疆理歷代國都之圖 |

| Revised Romanization | Honil Gangni Yeokdae Gukdo Ji Do |

| McCune–Reischauer | Honil Kangni Yŏktae Kukto Chi To |

| Short name | |

| Hangul | 강리도 |

| Hanja | 疆理圖 |

| Revised Romanization | Gangnido |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kangnido |

The Honil Gangni Yeokdae Gukdo Ji Do ("Map of Integrated Lands and Regions of Historical Countries and Capitals (of China)"[1]), often abbreviated as Kangnido, is a world map completed by the Korean scholars Kwon Kun and Yi Hoe in 1402, during the Joseon dynasty.[2]

It is notably the oldest extant Korean world map,[1] with two known copies that are both currently located in Japan. It is also one of the oldest surviving world maps from East Asia, along with the Chinese Da Ming Hunyi Tu (ca. 1398), which the Kangido is theorized to share at least one source with.[3] Both were revised after their production, making their original form uncertain. Still, the surviving copies of the Kangnido can be used to infer the original content of the Chinese map.

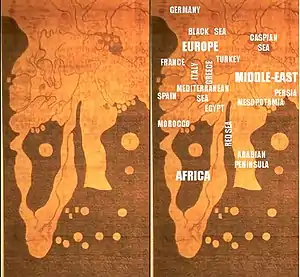

As a world map, it reflects the geographic knowledge of China during the Mongol Empire when geographical information about Western countries became available via Islamic geographers.[4] It depicts the general form of the Old World, from Africa and Europe in the west to Japan in the east.[5] Although, overall, it is less geographically accurate than its Chinese cousin, notably in its depiction of rivers and small islands. It does feature some improvements (particularly the depictions of Korea, Japan, and Africa).

Manuscripts

Only two copies of the map are known today. Both have been preserved in Japan and show later modifications.

The map currently in Ryūkoku University (hereafter, Ryūkoku copy) has gathered scholarly attention since the early 20th century. It is 158 cm by 163 cm, painted on silk. It is presumed that the Ryūkoku copy was created in Korea but it is not clear when the copy was brought to Japan. One claims that it was purchased by Ōtani Kōzui and others assume that it was obtained during the invasion of Korea (1592–1598) and given to the West Honganji temple by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[6] It contains some place names of Korea that are newer than 1402, suggesting that the Ryūkoku copy was partially modified from the 1402 original around the 1470s and 1480s.[7]

Another copy (Honkōji copy[8]) was discovered in the Honkōji temple of Shimabara, Nagasaki in 1988. It is 220 cm by 280 cm, much larger than the Ryūkoku copy, and painted on paper. It seems that the Honkōji copy was created in Japan during the Edo period.[9] The place names of Korea suggest that it was revised around the 1560s.[10]

There are two copies of maps in Japan that are related to the map. One (Honmyōji copy) housed in the Honmyōji temple of Kumamoto is known as the "Map of the Great Ming" (大明國地圖). The other (Tenri copy) at Tenri University has no title and is tentatively called by a similar name (大明國圖).[11] They are considered to be later adaptations of the original. The most important change is that place names of China are updated to those of the Ming dynasty while the original showed administrative divisions of the Mongol Yuan dynasty.

Based on a legend of the temple, it has been assumed naively that the Honmyōji copy was given to Katō Kiyomasa, the ruler of Kumamoto, by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in preparation for the Korean campaigns. However, the Seonjo Sillok of Korea reports that in 1593 the son of a Korean official who had surrendered to Katō copied and offered map(s) of China and Korea to him. This may refer to the extant Honmyōji map.[12]

Sources and contents

The Ryūkoku and Honkōji copies contain Gwon Geun's (權近) preface at the bottom. The preface is also recorded in his anthology named Yangchon Seonsaeng Munjip (陽村先生文集). According to Gwon, the map was based on the following four maps:

- the world map named Shengjiao Guangbei Tu (聲教廣被圖) by Li Zemin (李澤民)

- the historical map of China named Hunyi Jiangli Tu (混一疆理圖) by Qingjun (清浚)

- an unnamed map of Korea

- an unnamed map of Japan

In the fourth year of the Jianwen era (1402), Korean officials named Kim Sa-hyeong (金士衡) and Yi Mu (李茂), and later Yi Hoe (李薈), analyzed the two Chinese maps and combined these two maps into a single map. They thought that Li Zemin's map did not properly depict the region east to the Liao River (Liaodong) and Korea, they added the enlarged Korea, and also appended a map of Japan, premised about a similar map that was introduced to Korea from Japan in 1402.[2]

Li Zemin's world map

Li Zemin's world map is lost, and little is known about the creator Li Zemin. The Kangnido is a key map for reconstructing the content of Li's world map. Other extant maps considered to be based on Li's map are:

- a pair of maps named Dongnan Haiyi Tu (東南海夷圖) and Xinan Haiyi Tu (西南海夷圖),[13] which is recorded in the Guang Yu Tu (廣與圖) (1555) by Luo Hongxian (羅洪先), and

- the Da Ming Hun Yi Tu (circa 1389).[14]

There are possible literary references to Li's world map. An important clue is provided by Wu Sidao's (烏斯道) anthology titled Chuncaozhai Ji (春草齋集), where Wu stated that he had merged a map named Guanglun Tu (廣輪圖) and Li Rulin's (李汝霖) Shengjiao Beihua Tu (聲教被化圖). Although his own map is not known today, Wu seems to have referred to Li's map concerned because the Shengjiao Beihua Tu would be an alias for Shengjiao Guangbei Tu (聲教廣被圖) and Rulin appears to be Li Zemin's courtesy name. Wu stated that Li's map was newer than the Guanglun Tu (circa 1360). Based on place names on the map, earlier studies presumed that the source map had been created around 1319 and revised sometime between 1329 and 1338. However, Wu suggests that Li's map was created sometime after 1360. Most importantly, Korea's attempt to merge Chinese maps had at least one precedent in the Mongol era.[15]

As a world map, the Kangnido depicts the general form of the Old World, from Africa and Europe in the west to Japan in the east although the western portion is much smaller than its actual size. It contains the cartographic knowledge of Afro-Eurasia that cannot be found in China in the pre-Mongol period. Place names presented on the map suggest that the western portion of the map reflects roughly the situation of the early 14th century.[16] In the East, geographic information about the West was not updated in the post-Mongol period until Europeans such as Matteo Ricci brought Western knowledge.

Place names based on traditional Chinese knowledge and Islamic knowledge coexist separately. Their boundary line can be drawn from Besh Baliq to Delhi. Names based on Chinese geography were placed to the north and east of Besh Baliq even if they are actually located to the west. For example, the Talas River, a historic site for the Tang dynasty, was placed to the northeast of Besh Baliq although its actual direction is northwest. Similarly, India and Tibet are based on traditional Chinese knowledge, mainly gained by Buddhist pilgrimage up to the Tang dynasty. To the west of the "old" India, contemporary place names of India such as Delhi, Badaun and Duwayjir~Duwayqir (Persianized form of Devagiri) are shown. This suggests that information was acquired via the Ilkhanate.[17]

Western Turkestan, Persia, Arabia, Egypt and Anatolia are quite clearly delineated. These areas are depicted in great detail while place names are sparsely distributed in northwestern Eurasia. They correspond to the territories of Ilkhanate and the rival Golden Horde respectively, reinforcing Ilkhanate as the main source of information.[18]

There are about 35 African place names. The knowledge of the contour of Africa predates the European explorations of Vasco da Gama. In particular, the southern tip of Africa is quite clearly depicted, as well as a river which may correspond to the Orange River in Southern Africa. To the north of the African continent, beyond the unexplored "black" central mass, a pagoda is represented for the lighthouse of Alexandria, and the Arab word "Misr" for Cairo (al-Qāhira) and Mogadishu (Maqdashaw) are shown among others.[19] The Mediterranean forms a clear shape but is not blackened unlike other sea areas. The Maghreb and the Iberian peninsula are depicted in detail while Genoa and Venice are omitted. There are over 100 names for the European countries alone,[20] including "Alumangia" for the Latin word Alemania (Germany).

Historical map of China

The Hunyi Jiangli Tu by Zen monk Qingjun (1328–1392) was one of historical maps that were popular among Chinese literati. It showed historical capitals of Chinese dynasties in addition to contemporary place names. For example, it shows the capital of Yao, the legendary sage-emperor.

It followed Chinese tradition in that it was a map of China, not the world. But contrary to Song period maps which reflected limited Chinese knowledge on geography, it incorporated information on Mongolia and Southeast Asia. It also provided information of sea routes, for example, the sea route from Zayton to Hormuz via Java and Ma'bar (There remain traces on the Honmyōji and Tenri copies).[21]

Although Qingjun's map is lost, a modified edition of the map is contained in the Shuidong Riji (水東日記) by the Ming period book collector Ye Sheng (葉盛) (1420–1474) under the name of Guanglun Jiangli Tu (廣輪疆理圖). Ye Sheng also recorded Yan Jie's (嚴節) colophon to the map (1452). According to Yan, the Guanglun Jiangli Tu was created in 1360. The extant map was modified, probably by Yan Jie, to catch up with contemporary Ming place names. The original map covered place names of the Mongol Yuan dynasty.[22] Also, Yan Jie's map suggests that the western end of Qingjun's map was around Hotan.[23]

One may notice that the name of Qingjun's map Hunyi Jiangli Tu (混一疆理圖) bears a striking resemblance to that of the Kangnido, Hunyi Jiangli Lidai Guodu Zhi Tu (混一疆理歷代國都之圖) in Chinese. Actually, it is a combination of phrases common during the Mongol era. There were many preceding Chinese maps with similar titles, including the "Yu Gong Jiuzhou Lidai Diwang Guodu Dili Tu" (禹貢九州歷代帝王國都地理圖; Map of Capitals of Historical Emperors and Kings in the Nine Provinces of the Yu Gong).[24]

Map of Korea

Although Gwon Geun did not clarify which map was utilized for Korea, it is usually identified as Yi Hoe's Paldodo (八道圖). But the original condition of the Korean portion is unclear because even the oldest Ryūkoku copy reflects the administrative situation as late as around 1470.

Gwon Geun wrote that Li Zemin's map had many gaps and omissions concerning Korea. It is not clear how Korea was depicted on Li's map since Korea is out of the range of the extant derivative (southern half of the original).[25] The modified version of Qingjun's map provides a relatively proper shape of Korea though place names presented there are those of the preceding Goryeo dynasty.[26]

Note that, according to Gwon Geun, Korea was intentionally oversized (for practical reasons).

Map of Japan

The two original Chinese maps portray Japan as a set of three islands that lie from east to west. They would be influenced by the legend of Xu Fu. According to the Records of the Grand Historian, Xu Fu claimed that there were three divine mountains in the sea and went to one of the mountain-islands, which were later believed to be Japan.[27]

Japan is shown in better shape on the Ryūkoku copy than on traditional Chinese maps, but is rotated by 90 degrees. This drew attention from scholars and some even associated it with the controversy over the location of Yamataikoku, but the other three copies suggest that it is merely exceptional.[28]

Since information on Japan differs considerably among the four copies, the original condition is unreconstructible. The Honkōji copy resembles maps in the Haedong Jegukgi (1471), suggesting that information was regularly updated.[29]

The original source map, which Gwon Geun did not cite, either is usually identified as the one obtained in Japan supposedly in 1401 by Bak Donji (朴敦之), based on an article of the Sejong Sillok (the 10th month of 1438). However, Bak stayed in Japan from 1397 to 1399 as an envoy to the Ōuchi family of western Japan and therefore was not there in 1401. Japanese scholar Miya Noriko believes that the date was intentionally altered for political reasons (see below).[30]

Importance in Korea

This map originated from a historical setting of the Mongol Empire, which connected the western Islamic world with the Chinese sphere. The Mongol Empire demonstrated the conquest of the world by publishing treatises on geography and world maps. Their attempt enabled the integration of Islamic science and traditional Chinese knowledge. Note that the Chinese source maps were of "consumer use." In other words, they were not created by the empire for itself. It is presumed that the Mongol government gathered much more detailed information that was not disclosed to the public.[31]

The Chinese source maps were created by and circulated among literati of southern China, especially those in Qingyuan-lu (Ningbo). Qingjun, who was from neighboring Taizhou, created the historical map of Hunyi Jiangli Tu when he stayed in Qingyuan. Wu Sidao, who left an important bibliographic clue, was also from Qingyuan. In addition, Qingyuan-lu was one of the most important seaports from which the sea routes were extended to Fuzhou and Guangzhou, and Southeast Asia, Japan and Korea.

It is possible that these maps were available in Korea during the Mongol era. Korea, at the time under the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), was closely integrated into the Mongol Empire as a quda (son-in-law) state.[32] One supporting fact is recorded in the Goryeo-sa: Na Heung-yu (羅興儒) created a historical map based on maps of China and Korea and dedicated it to King Gongmin (r. 1352–1374).[33] Note that Gwon Geun served to the king as bichigechi (secretary).

Earlier studies presumed that the two Chinese source maps had been obtained during Kim Sa-hyeong's diplomatic trip to Ming China in 1399 although there is no literary evidence for his acquisition. It is more plausible that these maps came to Korea in different times since Gwon Geun's preface implies that Korean officials picked out the two maps for their excellency from among various sources, maybe including Wu Sidao's combined map.[34]

Japanese scholar Miya Noriko presumes that the year 1402 was a landmark for the reigning King Taejong of the newly founded Joseon dynasty. After a bloody succession struggle, Taejong ascended to the throne in 1400. In 1401, he was officially recognized as King of Joseon by the Chinese Emperor for the first time in the dynasty's history. In the 6th month of 1402, Yi Hoe's map of Korea was offered in a ceremony to celebrate his birthday. Then the project to combine it with Chinese and Japanese maps reportedly started in the summer (4th–6th months). This would be of symbolic significance in demonstrating royal power. This hypothesis also explains the factual error about the map of Japan. It was during the reigns of Taejo (1st king) and Jeongjong (2nd) that the map was obtained in Japan, but the date was altered to Taejong's reign.

Oddly enough, the Annals of Joseon Dynasty never mentions the map although it was obviously a national project. Another interesting fact is that this map uses the Ming Chinese era name Jianwen. After the Jianwen Emperor lost to Zhu Di in a civil war, the new emperor banned the use of the era name Jianwen in the 10th month of 1402. Thus the map should have used the era name Hongwu, not Jianwen. However, the era name Jianwen can be found even on the later Ryūkoku and Honkōji copies. This suggests that the Kangnido was never disclosed to the Chinese.[35]

This map demonstrates the cartographic stagnation in the post-Mongol era. The maps of common use were transformed into a symbol of national prestige and overshadowed by secrecy. As the extant copies show, Korean officials regularly updated the map by conducting land surveys and collecting maps from surrounding countries. Geographic information about the West was, however, not updated until the introduction of European knowledge in the 16–17th centuries.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Kenneth R. Robinson Choson Korea in the Ryukoku Kangnido in Imago Mundi, Vol. 59 No. 2 (June 2007) pp. 177–192, via Ingenta Connect.

- 1 2 Cartography of Korea, pgs. 235–345, Gari Ledyard al., (Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin, Madison), The History of Cartography, Volume Two, Book Two, Cartography in Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies, 1994, The University of Chicago Press, J. B. Harley and David Woodward ed., (Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI / Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI), pgs. slip cover, 243–247, ISBN 0-226-31637-8.

- ↑ 明代的古地图 (Ming Cartography), Cartography, GEOG1150, 2013, Qiming Zhou et. al., (Department of Geography, Hong Kong Baptist University), Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China, retrieved 27 Jan 2013; "Cartography". Archived from the original on 2007-09-07. Retrieved 2008-03-16..

- ↑ (Miya 2006; Miya 2007)

- ↑ Angelo Cattaneo Europe on late Medieval and early Renaissance world maps, International BIMCC Conference (Nov 2007)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:598–599,650)

- ↑ (Aoyama 1938:111–112; Aoyama 1939:149–152; Robinson 2007)

- ↑ The title of the Honkōji copy is written in seal script and difficult to read. Some earlier studies read "混一疆理歷代國都地圖." See (Miya 2006:601).

- ↑ (Miya 2006:599)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:14)

- ↑ Unno Kazutaka 海野一隆 (1957). "Tenri toshokan shozō Daimin koku zu ni tsuite" 天理図書館所蔵大明国図について. Memoirs of the Osaka University of the Liberal Arts and Education. A, Humanistic Science (in Japanese) (6): 60–67.

- ↑ (Miya 2006:600–601)

- ↑ (Takahashi 1963:92–93; Miya 2006:509–511)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:511–512)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:514–517)

- ↑ (Sugiyama 2007:80)

- ↑ (Sugiyama 2007:57–61,66-67)

- ↑ (Sugiyama 2007:61–66,67-68)

- ↑ (Sugiyama 2007:62–63)

- ↑ Peter Jackson, "The Mongols and the West", Pearson Education Limited (2005) ISBN 0-582-36896-0, p.330

- ↑ (Miya 2006:498–503)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:489–498)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:30)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:151–160)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:69–70)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:49–50)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:49–50,69-70)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:591–592; Miya 2007:237–240)

- ↑ (Miya 2007:241–242)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:588–590)

- ↑ (Miya 2006)

- ↑ Morihira Masahiko 森平雅彦 (1998). "Kōrai ō ika no kisoteki kōsatsu: Daigen urusu no ichi bunken seiryoku to shite no Kōrai ōke" 高麗王位下の基礎的考察--大元ウルスの一分権勢力としての高麗王家 [A Fundamental Study of Gao-li Wang Wei-xia: The Koryŏ Royal House as One Part of Dai-ön Yeke Mongɣol Ulus]. Chōsen shi kenkyūkai ronbunshū 朝鮮史研究会論文集 (in Japanese) (36): 55–87.

- ↑ (Miya 2006:583–584)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:516–517,580-583)

- ↑ (Miya 2006:586,596)

References

- Aoyama Sadao 青山定雄 (1938). "gendai no chizu ni tsuite" 元代の地圖について [On the map in the age of the Yüan Dynasty]. Tōhō Gakuhō 東方學報 (in Japanese) (8): 103–152.

- Aoyama Sadao 青山定雄 (1939). "Ri chō ni okeru ni san no Chōsen zenzu ni tsuite" 李朝に於ける二三の朝鮮全圖について. Tōhō Gakuhō 東方學報 (in Japanese) (9): 143–171.

- Miya Noriko 宮紀子 (2007). Mongoru teikoku ga unda sekaizu (in Japanese).

{{cite book}}:|script-journal=ignored (help) - Miya Noriko 宮紀子 (2006). "Kon'itsu Kyōri Rekidai Kokuto no Zu" e no michi" 「混一疆理歴代国都之図」への道. Mongoru jidai no shuppan bunka (in Japanese). pp. 487–651.

{{cite book}}:|script-journal=ignored (help) - Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3.

- Sugiyama Masaaki 杉山正明 (2007). "Tōzai no sekaizu ga kataru jinrui saisho no daichihei" 東西の世界図が語る人類最初の大地平. In Fujii Jōji 藤井讓治; Sugiyama Masaaki 杉山正明; Kinda Akihiro 金田章裕 (eds.). Daichi no shōzō: Ezu, chizu ga kataru sekai 大地の肖像: 絵図・地図が語る世界 (in Japanese). pp. 54–83.

- Takahashi Tadasi 高橋正 (1963). "Tōzen seru chūsei Islāmu sekaizu" 東漸せる中世イスラーム世界図. Ryūkoku Daigaku Ronshū 龍谷大学論集 (in Japanese) (374): 77–95.