| Kannemeyeriiforms Temporal range: Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

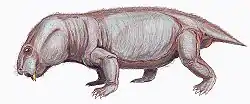

| Restoration of Stahleckeria potens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Infraorder: | †Dicynodontoidea |

| Clade: | †Kannemeyeriiformes von Huene, 1948 |

| Subgroups | |

Kannemeyeriiformes is a group of large-bodied Triassic dicynodonts. As a clade, Kannemeyeriiformes has been defined to include the species Kannemeyeria simocephalus and all dicynodonts more closely related to it than to the species Lystrosaurus murrayi.

Evolutionary history

Despite being the most species-rich group of dicynodonts in the Triassic Period, kannemeyeriiforms exhibit much less diversity in terms of their anatomy and ecological roles than the dicynodonts from the Permian Period.

Lystrosauridae is thought to be the most closely related group (sister taxon) to Kannemeyeriiformes, and since the earliest lystrosaurids are known from the Late Permian, the divergence of these two groups must have occurred at least as far back as this time, implying that a long ghost lineage must exist.[1] Although no kannemeyeriiforms have been found in the Late Permian yet, the recent discovery of Sungeodon helps fill a gap in the early fossil record of the group by showing that kannemeyeriiforms diversified right after the Permian-Triassic extinction event.[2]

Classification

Four families have been included in the group: Kannemeyeriidae, Shansiodontidae, Stahleckeriidae, and Dinodontosauridae.[3] Occasionally some of these families are not recognized, with most kannemeyeriiforms being placed in Kannemeyeriidae.[4] Recent phylogenetic analyses suggest that these families represent similar body plans or morphotypes rather than true evolutionary groupings.[1]

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from Szczygielski & Sulej (2023):[5]

| Kannemeyeriiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 Kammerer, C. F.; Fröbisch, J. R.; Angielczyk, K. D. (2013). Farke, Andrew A (ed.). "On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e64203. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864203K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064203. PMC 3669350. PMID 23741307.

- ↑ Maisch, M. W.; Matzke, A. T. (2014). "Sungeodon kimkraemerae n. gen. n. sp., the oldest kannemeyeriiform (Therapsida, Dicynodontia) and its implications for the early diversification of large herbivores after the P/T boundary". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 272: 1. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0394. edit

- ↑ Zavattieri, A. M.; Arcucci, A. B. (2007). "Edad y posición estratigráfica de los tetrápodos del cerro Bayo de Potrerillos (Triásico), Mendoza, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 44: 133–142. ISSN 1851-8044.

- ↑ Surkov, M.V.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "Head kinematics and feeding adaptations of the Permian and Triassic dicynodonts". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1120–1129. Bibcode:2008JVPal..28.1120S. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1120. S2CID 85792653.

- ↑ Szczygielski, T.; Sulej, T. (2023). "Woznikella triradiata n. gen., n. sp. – a new kannemeyeriiform dicynodont from the Late Triassic of northern Pangea and the global distribution of Triassic dicynodonts". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 22 (16): 279–406. doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2023v22a16.