| Capture of Montauban | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of the Somme, First World War | |||||||

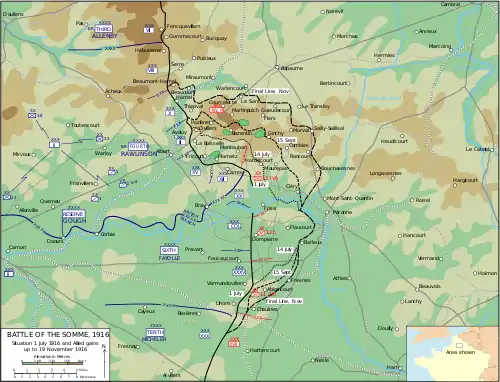

Battle of the Somme 1 July – 18 November 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sir Douglas Haig | Erich von Falkenhayn | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

30th Division 18th (Eastern) Division |

Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 6 Reserve Infantry Regiment 109 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,011 | 3,957 (incomplete) | ||||||

Montauban | |||||||

The Capture of Montauban (Monty-Bong to the British), took place on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, between the British Fourth Army and the French Sixth Army against the German 2nd Army, on the Western Front, during the First World War. Montauban is a commune in the Somme department in Picardy in northern France and lies on the D 64, between Guillemont to the east and Mametz to the west. To the north are Bazentin-le-Petit and Bazentin-le-Grand. Bernafay and Trônes woods are to the north-east and Maricourt lies to the south.

Military operations resumed in the area of Montauban in late September 1914 during the Race to the Sea, when the II Bavarian Corps and later the XIV Reserve Corps of the German 6th Army, attacked westwards down the Somme valley to reach Albert, Amiens and the sea. The attack was stopped just east of Albert by the French Second Army, which then attempted a reciprocal outflanking move further north and forced the 6th Army to fight a defensive battle as more troops were moved further north to attempt another advance around Arras, Lille and Lens.

On 1 July 1916, the German first defensive position ran south of the village, along the lower slopes of Montauban Spur. The junction of the British Fourth Army and XX Corps of the Sixth Army ran through Maricourt and to the east of Montauban. The 30th Division (XIII Corps) held the right of the corps area, next to the French 39th Division. Signs of an offensive by the British and French had been seen in May 1916 but German military intelligence anticipated an offensive against the Fricourt and Gommecourt spurs, with a possible supporting attack in between, rather than an attack further south around Montauban and the Somme river.

The 30th Division attacked behind a creeping barrage and captured its objectives of Montauban and the Montauban Ridge, inflicting many casualties on Bavarian Infantry Regiment 6, of the 10th Bavarian Division and Infantry Regiment 62 of the 12th Division. A German counter-attack in the early hours of 2 July was a costly failure. The 30th Division began operations against Bernafay and Trônes woods on 3 July. Montauban was recaptured by German troops on 25 March 1918 during Operation Michael, as the right flank units of the 17th (Northern) Division and the 1st Dismounted Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division retreated. The village was recaptured for the last time six months later on 26 August by the 18th (Eastern) Division, during the Second Battle of Bapaume.

Background

1914

On 25 September, during the Race to the Sea, a French attack north of the Somme against the II Bavarian Corps (General Karl von Martini (General)), forced a hurried withdrawal. As more Bavarian units arrived in the north, the 3rd Bavarian Division advanced along the north bank of the Somme, through Bouchavesnes, Leforest and Hardecourt until held up at Maricourt. The 4th Bavarian Division further to the north, defeated French Territorial divisions and then attacked westwards near Gueudecourt, towards Albert, through Sailly, Combles, Guillemont and Montauban. The village was captured on 28 September, against dug in French infantry and artillery of the northern corps of the French Second Army. Bavarian Reserve Infantry regiments 5 and 22, forced back the French 3rd Battalion, 69th Infantry Regiment and then attacked Maricourt. The Bavarian attack managed to advance half-way to Carnoy but was held up nearly 0.62 mi (1 km) short of Maricourt and the troops dug in after dark.[1]

The XIV Reserve Corps (Generalleutnant Hermann von Stein) attacked on 28 September, with the 26th Reserve Division and the 28th Reserve Division along the Roman road from Bapaume to Albert and Amiens, intending to reach the Ancre and then continue westwards along the Somme valley. The 28th Reserve Division advanced through Mametz close to Fricourt against scattered resistance from French infantry and cavalry. On 29 September, French counter-attacks at Fricourt almost succeeded; the German infantry were ordered to hold the village regardless of casualties and the French defence of Maricourt was equally effective. A lull followed and in October, both sides began to improve the ditches and shallow scrapes dug when the German advance had ended.[2]

In November 1914, the 28th Reserve Division was instructed to improve the fortifications in the divisional area, which included Montauban. Chalk spoil from digging was to be disguised by soil or turf, communication trenches should be deepened to 5 ft 7 in (1.7 m), trenches were to be lined by bricks and the overhead cover of dugouts and machine-gun nests was to be made thicker; sanitary conditions in the trenches were to be improved and trench junctions signposted. Units were to clarify their boundaries and survey the areas into which they could fire without endangering neighbouring units. Listening posts were to be equipped with bell pulls for warnings and linked by deeper communication trenches. Obstacles of barbed wire up to 3 ft 3 in (1 m) high, fencing and knife rests were to be kept ready to keep French patrols out of the trenches.[3] Attacks from 17 to 21 December by the 53rd Division were defeated, despite a chronic shortage of artillery ammunition, which led many appeals for fire support to go unanswered. On 21 December, artillery-fire was available to repulse an attack on the village, in which 1,200 French troops were captured and many more killed; a local truce was observed for the French to recover their wounded and dead but on Christmas Day there was no truce in the area.[4]

1915

In January 1915, General Erich von Falkenhayn the German Chief of the General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung, OHL), ordered a reconstruction of the defences which had been improvised when mobile warfare ended on the Western Front, late in 1914. Barbed wire obstacles were enlarged from one belt 5–10 yd (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two belts 30 yd (27 m) wide, about 15 yd (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) high. The front line had been increased from one trench line to a front position with three trenches 150–200 yd (140–180 m) apart, the first trench (Kampfgraben) occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) was kept for the bulk of the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet.[5]

Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yd (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strong points (the Stützpunktlinie) about 1,000 yd (910 m) behind the front line was also built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve position, renamed the second position, which was as well-built and wired as the front position. The second position was sited beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move guns forward before assaulting it.[6] The Second Army had fought the Battle of Hébuterne (7–13 June) on a 1.2 mi (1.9 km) front at Toutvent Farm, to the west of Serre, against a salient held by the 52nd Division and gained 3,000 ft (900 m) on a 1.2 mi (2 km) front, at a cost of 10,351 casualties, 1,760 being killed against a German loss of c. 4,000 men.[5]

1916

In February, following the Herbstschlacht (Autumn Battle; the dual Third Battle of Artois and the Second Battle of Champagne) in 1915, a third defensive position 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) back from the Stützpunktlinie was begun in February and was almost complete on the Somme front when the battle began. German artillery was organised in a series of sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors); each officer was expected to know the batteries covering his section of the front line and the batteries ready to engage fleeting targets. A telephone system was built, with lines buried 6 ft (1.8 m) deep for 5 mi (8.0 km) behind the front line, to connect the front line to the artillery. The Somme defences had two inherent weaknesses that the rebuilding had not remedied. The front trenches were on a forward slope, lined by white chalk from the subsoil and easily seen by ground observers. The defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front-trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stützpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,000 yd (1,800 m) and most troops within 1,000 yd (910 m) of the front line, accommodated in the new deep dugouts.[7]

The concentration of troops at the front line on a forward slope guaranteed that it would face the bulk of an artillery bombardment, directed by ground observers, on clearly marked lines.[7] Much of the new defence-building on the Somme began in the area north of Fricourt and work further south through Montauban to the river had not been completed by 1 July.[8] For nearly a year after the Battle of Hébuterne, the area became a backwater and the German divisions became known as the Sleeping Army. In May 1916, increased activity behind the British front line indicated that an offensive was being prepared.[9] On 10 and 19 July, the 28th Reserve Division repulsed attacks near Fricourt.[10] When Reserve Infantry Regiment 109 moved into the area of Mametz and Montauban in mid-June, the defences were seen to be poor and there had been far less fighting in the sector. Telephone connexions were inadequate and there had been little stocking of supplies and ammunition around the front line. By July, Reserve Infantry Regiment 23 had been brought up to Montauban, east of Reserve Infantry Regiment 109.[11]

Prelude

German preparations

In late May 1916, the 2nd Army (General der Infanterie Fritz von Below) on the Somme front was reinforced to eight divisions in line from Roye on the south bank north to Arras, with three divisions held in reserve. The Guard Corps (General der Infanterie Karl von Plettenberg) with three divisions took over from Gommecourt to Serre, which reduced the frontage of the XIV Reserve Corps from 30,000 to 20,000 yd (17 to 11 mi; 27 to 18 km), the 28th Reserve Division holding the line from Ovillers south to Maricourt. Recruit battalions of troops undergoing advanced training were moved closer to the front to occupy the second and third positions if needed; the 2nd Army had about 240 guns and howitzers, which were outnumbered 6:1 by the British artillery. In early June, the German defenders were confronted by British patrols but the front was mostly quiet until 20 June, when British heavy guns began to bombard the area behind the German front line, as far back as Bapaume, until 23 June.[12]

The German front line opposite XIII Corps had been developed into a front position with several lines of trenches linked by communication trenches and a new reserve line about 700–1,000 yd (640–910 m) further back, from Dublin Trench to Train Alley and Pommiers Trench; a communication trench known as Montauban Alley had been dug below the skyline, along the north facing (reverse slope) of Caterpillar Valley. A second position existed about 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) further back from Maurepas to Guillemont, Longueval and the Bazentin villages.[13] The third position was incomplete and the second position was not as elaborate as the defences to the north, the ground being mainly clay and soil, unlike the chalk characteristic of the terrain further north.[14] All available labour was absorbed in keeping the first position in repair during the preparatory bombardment. In the 12th Division area, the second position was a shallow trench and work had only begun on the third position.[15] The front position had been made more formidable, with the strong points of The Castle, along with Glatz and Pommiers redoubts, made by blocking trenches and encircling them with barbed wire. Montauban had been fortified and a trench dug around the south side.[13]

On the night of 28/29 June, Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 6 (BIR 6) of the 10th Bavarian Division was sent forward to relieve the troops on either side of Montauban, which had been reduced by the British and French preliminary bombardment to about thirty men. Many of the fortifications were found to have been demolished and only three shelters were relatively safe. The relief had been chaotic with vague orders and an unclear chain of command.[16][lower-alpha 1] BIR 6 took over from the north bank of the Somme to the road between Montauban and Carnoy, with the rest of the division in reserve near Bapaume or in the line near Thiepval. The 12th Division was in support, Infantry Regiment 63 opposite the French XX Corps and Infantry Regiment 62 behind Montauban. Reserve Infantry Regiment 109 of the 28th Reserve Division held the line from the Carnoy road, westwards to Mametz.[17] On the following night an attempt was made to relieve Reserve Infantry Regiment 109 with Infantry Regiment 23 of the 12th Division but the extent of British artillery-fire prevented more than 1+1⁄2 companies reaching the front line, the rest waiting at Montauban.[13] Most of the artillery and ammunition of the 12th and 28th Reserve divisions in the valley north of Montauban and Mametz was destroyed. Opposite the 30th Division, much of the garrison and most of the machine-guns had been destroyed by the bombardment.[15]

British preparations

Early in May 1916, preparations for the offensive quickened and long convoys of lorries and carts moved constantly on roads behind the front line. After dark, trains delivered ammunition and material was carried to the front line. New trenches were dug and sandbag revetments were constructed for gas cylinders. The woods behind the British front line filled with men and guns. The Germans were little able to impede the preparations due to lines of balloons, from which observers detected all daylight movement behind the German front line and directed heavy artillery-fire on it. British aircraft flew over the German lines unopposed, photographing German defences and lines of communication, bombing shelters and artillery emplacements and strafing parties of infantry and cavalry. When German observation balloons ascended, they were attacked by aircraft and shot down.[12]

The British XIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Walter Congreve) held the front line from Maricourt next to the French XX Corps, westwards to Carnoy. The front line was close to the bottom of the forward (south-facing) slope of a valley between the Maricourt and Montauban ridges and the German front line was further up the slope. Maricourt Ridge declines to the east into the Hardecourt Valley which contains the woods of Bois d'en Haut and Bois Favière. Beyond Montauban on the crest of the ridge lies Caterpillar Valley, beyond which are the Ginchy–Pozières ridges. A valley containing Carnoy divides into a northern branch with a pre-war light railway known as Railway Valley with a long tree plantation known as Talus Boisé (wooded embankment) along the eastern slope. The XIII Corps divisions had to ascend a long, low slope, which was almost flat on the 30th Division front, cut with depressions adjacent to the Carnoy and Mametz spurs and Railway Valley, which curved eastwards below Montauban.[18]

British plan

The XIII Corps plan for the 30th Division, issued on 15 June, was to capture Montauban on the first day; to the east of the village Nord Alley and Dublin Trench were to be captured to form a defensive flank to the French 39th Division at Dublin Redoubt. West of the village, the advance was to reach Montauban Alley and gain observation into Caterpillar Valley. The first objective was set at a German reserve line known as Dublin Trench and Pommiers Trench, about 1,000 yd (910 m) from the British front line. In the centre and on the left flank the advance was to continue to Montauban and the Montauban–Mametz Ridge and then the left flank was to advance a short distance, to improve the observation over German positions on the left.[19]

If the first phase succeeded and the attack further west captured Fricourt, XIII Corps was to wheel to the right by pivoting on Favière Wood and Dublin Redoubt. The third phase consisted of an eastwards advance via Bernafay and Trônes woods to the German second position from Falfemont Farm to Guillemont. When the plan was settled by Operation Order 14 on 23 June, the 30th Division dug a new front line trench about 150–200 yd (140–180 m) closer to the German front line and six communication trenches between Maricourt on the right and Talus Boisé (wooded slope) on the left at the boundary with the 18th (Eastern) Division.[20][19]

The infantry advance was to be assisted by a heavy artillery barrage which was to fall successively on German defensive lines and a field artillery barrage which was to creep forward.[21][lower-alpha 2] The short lifts of the creeping barrage were to reach points registered beforehand so that the advance of the barrage would fall on each length of trench obstructing the advance, each battery firing along a lane. Barrage lifts were determined by time-table, based on the assumption that delays in the infantry advance to wait for the barrage to move on, were preferable to the risk of it moving too fast and allowing German troops time to emerge from shelters and engage the infantry with small-arms fire. The British infantry were to keep as close to the creeping barrage as possible and six artillery lifts were synchronised with the stages of the infantry advance. The 9th (Scottish) Division in corps reserve, was to move forward to sheltered localities about 2 mi (3.2 km) behind the old front line.[21]

Two brigades of the 30th Division were to advance to the first objective, a line from Dublin Trench to Glatz Redoubt, in two stages by 8:28 a.m. The right-hand brigade was to stop at Casement Trench, which extended west from Dublin Redoubt and the brigade on the left was to reach Train Alley, 150 yd (140 m) west of Glatz Redoubt and to attack the redoubt. The third brigade was then to advance up Railway Valley and at 9:30 a.m. and pass through the leading brigades, to capture Montauban. On the left flank, the 18th (Eastern) Division was to advance parallel with the 30th Division. As the final objectives were reached, strong points were to be built by a Field Company section of the Royal Engineers (RE) and detachments from two pioneer battalions, which were attached to each brigade. Parties of infantry and machine-guns were to move forward to La Briqueterie, which had a chimney used by the Germans as an observation point and other areas useful for British artillery observation. Several batteries of field guns were to move forward to command ground between the new front line and the German second position and a box-barrage was to be fired around Montauban to deter a German counter-attack.[23]

Preparatory bombardment

On 20 June, British heavy artillery bombarded German communications behind the front line as far back as Bapaume and then continued intermittently until the evening of 22 June.[24][lower-alpha 3] At dawn on 24 June, a shrapnel barrage began on the German front position and villages nearby. At noon more accurate fire began and in the evening a light rain turned the German positions into mud. On 25 June, heavy artillery-fire predominated, smashing trenches and blocking dugouts, setting fire to supply dumps and causing large explosions in Montauban. Variations in the intensity of fire indicated likely areas to be attacked; the greatest weight of fire occurring at Mametz, Fricourt and Ovillers. During the night the German commanders prepared their defences around the villages and ordered the second line to be manned. After an overnight lull, the bombardment increased again on 26 June then suddenly stopped. The German garrisons took post, fired red rockets to call for artillery support and a German barrage began on no man's land.[25]

Later in the afternoon, huge mortar bombs began to fall, destroying shallower dug-outs and a super-heavy gun bombarded the main German strong-points, as smaller guns pulverised the villages close to the front line, from which civilians were hurriedly removed. German troops billeted in villages moved into the open to avoid the shelling and from 27 to 28 June, heavy rain added to the devastation, as the bombardment varied from steady accurate shelling to shell-storms and periods of quiet. At night British patrols moved about no man's land and on the 30th Division front found German trenches lightly held. Raiders, taken prisoner by the Germans, said that they were checking on the damage and searching for German survivors. On 27 June, a large explosion was seen in Montauban and two raids during the night found German trenches empty, while a third party found more Germans above ground than the night before. German interrogators gleaned information suggesting that the offensive would begin on either side of the Somme and Ancre rivers at 5:00 a.m. on 29 June.[25]

The German infantry stood to along with reinforcements but the bombardment resumed in the afternoon, rising in intensity to drumfire several times. Artillery-fire concentrated on small parts of the front and then lines of shells moved forward into the depth of the German defences. Periodic gas discharges and infantry probes continued; German sentries watching through periscopes were often able to warn the garrisons in time.[25] On 30 June, the bombardment repeated the earlier pattern, by when much of the German surface defences had been swept away, look-out shelters and observation posts were ruined and communication trenches had disappeared, particularly on the front of XIII Corps and XV Corps.[26] The headquarters of Reserve Infantry Regiment 23 was destroyed by a shell on 23 June and by 1 July, the systematic bombardment had cut the wire around Montauban, destroyed the German trenches and hit the German artillery in Caterpillar Valley. The infantry took cover in the deeper dug-outs or shallow support trenches.[27] On the night of 30 June/1 July, the bombardment fell on rear defences and communication trenches, then at dawn, British aircraft "filled the sky", captive balloons rose into the air at 6:30 a.m. and an unprecedented barrage began all along the German front until 7:30 a.m., when the bombardment abruptly stopped. The remaining German trench garrisons began to leave their shelters and set up machine-guns in the remains of trenches and in shell-holes, which proved difficult to spot and from which the occupants could face in any direction to engage an attacker.[28]

Battle

1 July

30th Division

At 7:22 a.m. a hurricane bombardment was fired by six Stokes mortar batteries, which had been placed in Russian saps opened during the night. Eight minutes later the 89th Brigade attacked on the right of the division, the two leading battalions advancing quickly across the 500 yd (460 m) of no man's land with slung rifles, in extended lines of companies, about 100 paces apart. The rearward companies advanced before time, to avoid a sparse German counter-barrage which began as soon as the infantry moved forward. The German wire was found to be well cut; German troops in the front line were caught below ground sheltering from the bombardment and 300 prisoners were taken, mostly from Infantry Regiment 62.[29]

After a pause the two battalions moved forward to Casement Trench and Alt Trench, taking prisoners from German's Wood on the way. After waiting for the standing barrage to lift the infantry advanced to the first objective at Dublin Trench, which was found empty at 8:30 a.m. as the 3rd Battalion of the French 153rd Infantry Regiment occupied Dublin Redoubt. Consolidation began, using the picks and shovels carried by the supporting battalions, with the left flank on Glatz Redoubt. The trench had been so badly damaged by the bombardment that some troops overshot and dug in 50–100 yd (46–91 m) forward by connecting shell-holes; three field artillery batteries moved forward near Maricourt.[29]

On the left, the 21st Brigade reached the German front line with few casualties and caught the Germans before they could emerge from their shelters. The two leading battalions advanced up the east side of Railway Valley close up to the creeping barrage, until just before Alt Trench, where they took the trench as the barrage lifted at 7:45 a.m. The left-hand battalion was caught by enfilade machine-gun fire, from the far side of Railway Alley, which caused many casualties and a supporting battalion was also engaged by machine-gun fire as it crossed no man's land and only a few men got across.[30][lower-alpha 4] Two mopping-up parties were sent westwards to engage German troops, who had got out of their dug-outs in time and begun counter-attacking eastwards. Thirty-one prisoners were taken and a large number of troops from Infantry Regiment 109 retreated through the artillery lines in Caterpillar Valley. The way was cleared for the left-hand battalion, which ran up Train Alley and overran the machine-gun nest. The advance of the brigade continued, reached Glatz Redoubt at 8:35 a.m. and gained touch with the 89th Brigade.[30]

The 90th Brigade had assembled west of Maricourt at 2:30 a.m. and at 8:30 a.m. the two leading battalions advanced in lines of companies, each company making lines of half-platoons which advanced in files, with the third battalion following closely. The battalions moved forward east of Talus Boisé (wooded slope) which was sheltered by Railway Valley and further on, the infantry was protected by a smoke screen along Dublin Trench, raised by the leading brigades. As soon as the advance began it was bombarded by German artillery but with little effect because of the state of the ground, which smothered shell explosions and the formation adopted for the advance. A German machine-gunner behind the former German front line trench near Breslau Alley caused many casualties to the brigade, having already engaged the 18th (Eastern) Division but the troops reached Train Alley fifteen minutes early and waited for the bombardment to lift, during which the machine-gun nest on the left flank was located and silenced by a Lewis gun crew. The barrage lifted and the front wave rushed forward. A smoke barrage screened the advance forward of Glatz Redoubt, which reduced visibility in Montauban and Caterpillar valley to 2 to 3 yd (1.8 to 2.7 m). The trench around Montauban was empty and the infantry who entered at 10:05 a.m. found the village deserted, except for a fox.[32]

The British troops moved through the village, followed up by the second line and as the smoke screen dispersed around 11:00 a.m. the second objective in Montauban Alley beyond the village was entered and another hundred prisoners were taken. Across the valley beyond, hundreds of German troops were seen retreating along the road to Bazentin-le-Grand and quickly brought under artillery-fire by forward artillery observers. Troops of the 16th Manchester Regiment (16th Manchesters) rushed German field artillery positions in Caterpillar Valley, forced back the crews of Field Artillery Regiment 21, after the German infantry had fallen back through the gun positions and captured three guns. The German artillerymen were machine-gunned from Montauban and strafed by aircraft from 150 ft (46 m) above as they retired but they returned during the night and recovered three guns. The British began to consolidate the captured positions and a hot meal was brought forward. After 1:45 p.m. German artillery-fire on the village from the north and east caused many casualties.[33]

By noon, reports had reached German headquarters that British troops were in Bernafay and Trônes woods but with so few troops available, no counter-attack could be contemplated. Cooks and clerks were mobilised with recruit companies to occupy the second position.[15] At 11:30 a.m. the British heavy artillery began to bombard La Briqueterie and at 12:30 p.m., a company of the 20th King's Liverpool Regiment of the 89th Brigade advanced from Dublin Trench behind a creeping barrage. A party of bombers moved up Nord Alley from Glatz Redoubt to block the retreat of the garrison. No resistance was met until the far side was reached where a machine-gun was silenced. The commander of Infantry Regiment 62 and three staff officers were captured. The 12th Reserve Division near Cambrai, received orders from the XIV Reserve Corps headquarters at 1:35 p.m., to move up to Rancourt and Bouchavesnes, about 6–7 mi (9.7–11.3 km) from Montauban. At 1:30 p.m. the division was ordered to attack the Montauban–Mametz ridge during the night but by midnight the foremost units had only reached the second position.[34]

Air operations

9 Squadron Royal Flying Corps (RFC) flew over XIII Corps and an observer watched the troops of the 30th Division advance to a line from Dublin Trench to Glatz Redoubt, at 8:30 a.m. Another aircraft arrived at 10:00 a.m. and the crew saw the reflectors sewn onto the small packs of the infantry glinting, as they advanced from Glatz Redoubt along Train Alley towards Montauban. The crew saw a German field artillery battery setting up in Bernafay Wood and attacked the gunners with machine-gun fire, from an altitude of 700 ft (210 m).[35]

The flyers saw German troops in trenches to the east of the wood and engaged them with the machine-gun. As the crew flew back, they saw the 16th Manchester enter Montauban and troops of the 18th (Eastern) Division coming up on the left, flying low over the ridge to wave at the infantry. By 11:15 a.m. flashes from the reflectors were seen along the northern fringe of Montauban and a sketch was drawn for the infantry headquarters, showing the extent of the advance onto Montauban Ridge. Balloon observers and the crews of artillery-observation aircraft spent the day spotting German artillery and directing counter-battery fire onto them, although the quantity of shell-bursts was so great that only approximate corrections could be given.[35]

18th (Eastern) Division

_Division_WW1.svg.png.webp)

The 18th (Eastern) Division was to attack with all three brigades, up the Carnoy Spur and the south end of the Mametz Spur on the left of the XIII Corps area, to the first objective along Train Alley and Pommiers Trench. After a pause, the brigades were to advance to a second objective at Montauban Alley, from Montauban west to Pommiers Redoubt, which was on a commanding position along the Montauban–Mametz road, an advance of 2,000 yd (1,800 m). A third objective was set another 400 yd (370 m) forward on the left flank, to capture part of the Montauban Spur overlooking Caterpillar Wood. The bombardment plan of the division was similar to that of the 30th Division, except for the advance to the second and third positions, which was to be covered by a shrapnel bombardment, moving forward slowly at a rate of 100 yd (91 m) in three minutes, until beyond the final objective. Arrangements were made with XV Corps to bombard the length of Pommiers Trench from the left flank.[23]

Strong points were to be built by a Field Company Royal Engineers and detachments from two pioneer battalions attached to each brigade. The division was to raid Caterpillar Wood and prevent the withdrawal of German artillery from the valley.[23] Mine warfare had been conducted by both sides during May, which left a devastated area in front of Carnoy near the Carnoy–Montauban road of about 150 yd (140 m), which had prompted the Germans to fill the front trench with barbed wire and obstacles, then retire to the support line, except for some fortified craters. The 55th and 53rd brigades were to pass either side, while the 55th Brigade cleared the area, with a large flamethrower at the end of a Russian sap. As part of the Mines on the first day of the Somme, a 5,000 lb (2.2 long tons; 2.3 t) mine was sprung at 7:27 a.m. under a German salient at Kasino Point and a 500 lb (230 kg) mine was blown on the extreme left flank, intended to collapse German dugouts and destroy machine-gun nests.[36] (In 1971, Martin Middlebrook wrote that the Kasino Point Salient was between Mametz, Carnoy and Montauban and the mine planted there was one of seven large mines that were due to be detonated on 1 July.)[37]

During tunnelling, the British broke into a German dugout but were able to cover it up before the breach was noticed.[38] (In 1932 James Edmonds wrote that this incident occurred during the digging of Russian saps rather than the Kasino Point mine.)[39] Though the mines on the British front were to be blown at 7:28 a.m., the Kasino Point mine was late because the officer in charge hesitated when he saw that British troops near Kasino Point had left their trenches and begun to advance across no man's land. The German machine-gunners at the point opened fire and inflicted many casualties; the officer detonated the mine which instead of exploding upwards, sent debris outwards over a wide area, causing casualties among at least four British battalions, as well as obliterating several German machine-gun nests. A witness wrote later,

I looked left to see if my men were keeping a straight line. I saw a sight I shall never forget. A giant fountain, rising from our line of men, about 100 yards from me. Still on the move I stared at this, not realizing what it was. It rose, a great column nearly as high as Nelson's Column, then slowly toppled over. Before I could think, I saw huge slabs of earth and chalk thudding down, some with flames attached, onto the troops as they advanced.

but the late detonation surprised and demoralised the Germans, whose fire diminished and the British swept over the German front trenches, making it the most successful mine detonation of 1 July.[41] Several casualties were suffered by the battalion nearest to the Kasino Point mine. The three brigades had advanced from repaired trenches and taped lines, rather than from new jumping-off trenches to disguise the imminence of the attack.[36]

The infantry advanced behind a creeping barrage over no man's land, which was about 200 yd (180 m) wide. Troops of Reserve Infantry Regiment 109 (RIR 109) and Infantry Regiment 23 (IR 23) had garrisoned the area but on the day, most prisoners were from Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 6 (BRIR 6), due to the number of casualties inflicted by the preparatory bombardment. On the east side of the crater area, some German soldiers had survived the bombardment but those in the west end had been swamped by a flame projector and killed. Machine gunners in the crater area were able to fire along no man's land into the left of the 55th Brigade battalions on the right flank, which caused many casualties, confusion and delay. The Germans opposite had time to man the support trench and strong points further back and when the creeping barrage moved on, about 300 German troops engaged the attackers with small-arms fire. By 8:37 a.m. the right-hand battalion had become pinned down in the German support line, blocked by The Warren to the front and the machine-guns in the crater field on the left.[42]

Just after 9:00 a.m., the advance of the 30th Division on the right into Glatz Redoubt and Train Alley, threatened the retreat of the Germans opposite the 55th Brigade and some began to drift back towards Montauban; the right-hand battalion of the 55th Brigade was able to get forward towards Train Alley but no further. The left-hand battalion was still short of Breslau Support Trench. The 53rd Brigade in the centre had advanced west of the Carnoy road, assisted by the flame projector which killed the Germans on the west side of the Carnoy crater field and the mine under Kasino Point, which had destroyed a machine-gun post and demoralised the survivors, some of whom surrendered immediately. The leading battalions crossed the front and support lines easily, except on the right flank, where Germans in The Castle and in Back Trench behind the front line caused a short delay before The Castle was captured. The left-hand battalion by-passed Back Trench and attacked Pommiers Trench, the intermediate line on Montauban Ridge. Three German machine-guns had survived the bombardment and stopped the advance until a party of bombers moved up Popoff Lane and silenced one of the machine-gun crews with hand grenades and by 7:50 a.m. Pommiers Trench was captured and consolidation began. Troops in The Loop at the right of Pommiers Trench held out and caused many casualties. Bombing parties tried to get close but found the trenches blocked and a Stokes mortar crew which was sent forward towards Pommiers Redoubt also found the approaches blocked.[43]

The 54th Brigade on the left advanced up the south side of Mametz Spur between the craters of the two mines and crossed the German front and support trenches, until a machine-gun at The Triangle caused many casualties in the right-hand battalion, before being rushed. The left-hand battalion moved so fast over Mametz Spur that it reached Pommiers Trench before the standing barrage lifted and had to wait until 7:50 a.m. to occupy the trench. Bombing parties had pushed ahead of the main force and taken Black Alley, which led to Pommiers Trench. Preparations began for the 53rd and 54th brigades to advance over the ridge to the second objective of Pommiers Redoubt, Maple Trench and Beetle Alley. On the extreme right the division was close to the first objective and on the left had reached it but in the centre, most of the 53rd Brigade was held up in front of Breslau Support Trench and the troops near The Loop were still pinned down. The attack on Pommiers Redoubt, a battalion headquarters of RIR 109 began at 8:30 a.m. with a battalion each from the 53rd and 54th brigades. The redoubt was on the flat top of the Montauban Spur and had not been extensively bombarded and as the infantry advanced behind a creeping barrage against massed machine-gun and rifle fire, the attacks broke down in front of the German wire.[44]

An outflanking attempt was made from the west, British troops got into Maple Trench and fired along the south face of the redoubt, where the German infantry had their heads and shoulders above the parapet. During the surprise, most of the two attacking battalions had infiltrated towards the east side and got into the redoubt through gaps in the wire. After fighting hand-to-hand fight for an hour, the garrison was overwhelmed and Maple Trench was also captured. Both sides lost many casualties and the creping bombardment had advanced far beyond. Despite the left of the 53rd Brigade not having come level and the 91st Brigade of the 7th Division to the left being delayed, the advance continued to Beetle Alley just beyond the creeping barrage and the British bombed their way in at 10:15 a.m. The Germans in the trench and Montauban Alley resisted attempts to move eastwards and an inconclusive bombing fight began, ending the advance of the 53rd and 54th brigades. Further east, the 55th Brigade advance had just begun, despite the plan requiring the north face of Montauban Ridge to have been reached by 10:00 a.m. The right flank was short of Train Alley, the centre was stuck near the German front trench and the objective had been reached on the left flank. At 9:30 a.m. a clearing party managed to overrun the Germans at the Carnoy craters but the defenders of Breslau Support Trench and The Loop held on.[45]

The reserve battalion of the 55th Brigade went forward spontaneously against continuous small-arms fire from The Loop but two companies were shielded by the Carnoy Spur and advanced to the battalion held up below Train Alley. The companies on the left arrived later; both battalions reached the Montauban road by noon, seen by the crew of a contact patrol aircraft. The British advances on the flanks threatened the retreat of the Germans in Breslau Support and The Loop and many of the survivors began to retire. By 10:00 a.m., an attack along the communication trenches nearby had occupied the area and taken 90 prisoners from RIR 109 and IR 62. The attackers got into the west end of Train Alley and on the west side of the area, about sixty Germans in The Loop surrendered at 10:20 a.m. The last German post in Back Trench near Breslau Alley held out until 152 Germans, mostly from BRIR 6 surrendered at 2:00 p.m. The remaining British troops in the area, were able to advance to the Montauban–Mametz road by 3:00 p.m. and then take part of Montauban Alley at 5:15 p.m. after a mortar bombardment, at which the German survivors retreated into Caterpillar Wood.[46]

Troops which had captured Pommiers Redoubt bombed along Pommiers Trench for 400 yd (370 m) to White Trench by 3:30 p.m. and were joined by the troops who had moved along Loop Trench after the fall of The Loop at 5:40 p.m., despite German snipers using automatic rifles to stop any movement over the ground. Both parties then occupied the last length of Montauban Alley, which completed the capture of the second objective of the 18th (Eastern) Division. Parties began to move along Caterpillar Trench close to Caterpillar Wood and build trench blocks and advanced parties were established at the third objective which overlooked Caterpillar Wood, with the right flank in touch with the 55th Brigade west of Montauban. In the 54th Brigade area, two battalions worked forward to the third objective at White Trench on the north face of Montauban Ridge by 4:00 p.m. and dug in, as supporting battalions began to consolidate the captured ground and repair destroyed German trenches. Field artillery moved forward to Carnoy and two battalions of the 9th (Scottish) Division were attached to the 18th (Eastern) Division to carry stores and help dig new strong points.[47]

2 July

The 12th Reserve Division began to arrive from Cambrai during the afternoon of 1 July. By the afternoon the survivors of the 28th Reserve Division and BRIR 6 of the 10th Bavarian Division, had withdrawn to the Braunestellung (second position) from Guillemont to Longueval and Bazentin le Grand. Bernafay and Trônes woods were left undefended and the only German reserve was Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16, between Longueval and Flers. The 12th Reserve Division was rushed forward at 9:00 a.m. and marched to the area between Combles and Ginchy, where it was put under the command of the 28th Reserve Division and ordered to recapture Montauban and Favières Wood.[48] Overnight, Below ordered the garrison of Fricourt to withdraw.[49] During the night, news arrived at the 2nd Army headquarters that Thiepval had been held and that Schwaben-Feste had been recaptured.[50]

Reserve Infantry Regiment 51 (RIR 51) was ordered to advance south of the Bapaume–Albert road past Combles to enter the north-eastern corner of Montauban. In the centre, RIR 38 was to recapture Bois Favières and RIR 23 was to attack between Curlu and Maurepas, the first troops to cross the Maurepas–Ginchy road from 7:00–8:00 p.m. When RIR 51 reached Guillemont, two battalions of Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16 (BIR 16) between Waterlot Farm and Longueval were to advance southwards towards Montauban Alley, Montauban and Pommiers Redoubt; RIR 51 was to recapture Dublin Redoubt, La Briqueterie and Montauban. The eastern side of the salient formed at Montauban and the ridge was threatened by the attack but it took until midnight for the reinforcements to reach the Maurepas–Ginchy road and it was dawn before the infantry passed either side of Bernafay Wood. BIR 16 stumbled into a British outpost north of Montauban in the dark, the alarm was raised and a British SOS barrage fell on the area, forcing the Germans back into Caterpillar Valley. To the south, RIR 51 arrived at La Briqueterie in an exhausted and disorganised condition, looking like "a mass of drunken men", who were forced back by machine-gun fire. French troops repulsed the other two regiments and took several prisoners.[51]

The attack had been made from 3:00 to 4:00 a.m. on a front of 4 mi (6.4 km), with exhausted troops who suffered many casualties; the survivors were withdrawn to Grunestellung, an intermediate line about 1,000 yd (910 m) in front of the second position, between Maurepas and Guillemont.[51] A new defensive front was established behind Montauban, from Maurepas northwards to Bazentin-le-Petit Wood. It was not possible for the Germans to counter-attack again on 2 July, because the 10th Bavarian Division had been used to reinforce the most threatened sectors and to join the failed counter-attack. The 185th Division had occupied the new line and also provided reinforcements, the 11th Reserve Division would not arrive until 3 July and the 3rd Guard, 183rd and 5th divisions, were the only reserves close to the Somme front. On the morning of 2 July, the 30th Division artillery tried to set Bernafay Wood alight with 500 thermite shells; later on patrols found many dead German soldiers in the wood and took 18 prisoners, from RIR 51. Consolidation continued along with reconnaissance and artillery registration, the front being quiet, except for a German bombardment of Montauban area.[52]

Aftermath

Analysis

Oberst (Colonel) Leibrock, commander of BRIR 6, had been taken prisoner and after the war wrote that the regiment had not been placed under the command of the 28th Reserve Division and the 12th Division until the British–French preparatory bombardment had begun. There had been a lack of material to build dug outs and obstacles and the work could not be done in daylight. The regiment had been split, battalions assigned elsewhere and companies had been used piecemeal as reinforcements. On 1 July, the commander lost telephone communication with most of the regiment and had no control over the supply of food and ammunition. Leibrock wrote that it would have been better to move the regiment into line as a unit and move neighbouring units sideways. The infantry had fought a determined defensive battle and had been overwhelmed. In 2005, Jack Sheldon wrote that the 2nd Army had lost the initiative on the Somme during the preliminary bombardment, rather than on 1 July and that the defence of the area south of the Albert–Bapaume road was conducted in an atmosphere of crisis, in which units were thrown into battle to plug gaps rather than as formed units, which increased German loses.[53]

The success of the 30th Division was ascribed to the efficiency of the artillery support and the infantry training before the attack, particularly in open warfare and "mopping-up", to prevent parties of Germans emerging in overrun ground, engaging the troops ahead and preventing supporting and reserve units from following up. Feints had induced German artillery to return fire and disclose the ground on which the guns were ranged, which was traversed quickly.[54] The Germans had been defeated on a 1,500 yd (1,400 m) front and pushed back for 2,000 yd (1,800 m) for a loss of 501 prisoners and three field guns. By noon the 30th Division was established on Montauban Ridge and had observation into Caterpillar Valley. The 18th (Eastern) Division on the left had yet to come up but on the right, the French 39th Division was ready to advance again. The 30th Division had suffered relatively few casualties and the 9th (Scottish) Division was ready but the disastrous consequences of the British attacks further north led to the division being ordered to wait on the 18th (Eastern) Division. Patrols went forward and found Bernafay Wood nearly empty but before the attack, it had been stressed that the division must prepare to defend Montauban against German counter-attacks which were considered inevitable. Consolidation went on all night and four communication trenches were dug across no man's land. By 6:00 p.m. the Maricourt–Montauban road had been repaired to a point 200 yd (180 m) short of the old German front line.[55]

Casualties

The 30th Division suffered 3,011 casualties, the 18th (Eastern) Division 3,115. RIR 109 suffered 2,147 casualties and BRIR 6 1,810. The Bavarian Official History recorded that BRIR 6 suffered 3,000 casualties, only 500 men surviving, most in units which had not been engaged; only a few stragglers turned up the next morning.[56] In 2013, Ralph Whitehead wrote that BRIR 6 suffered 1,761 casualties on 1 July, the second worst loss after RIR 109. IR 62 fought near Montauban and had 737 casualties.[57]

Subsequent operations

July 1916

At 9:00 p.m. on 3 July, the 30th Division occupied Bernafay Wood, suffering only six casualties and capturing seventeen prisoners, three field guns and three machine-guns. Patrols probed eastwards, discovered that Trônes Wood was defended by machine-gun detachments and withdrew. Reports from the advanced troops of the divisions of XIII Corps and XV Corps, indicated that they were pursuing a beaten enemy. A combined attack by XX Corps and XIII Corps on 7 July, was postponed for 24 hours, because of a German counter-attack on Favières Wood in the French area. The British attack began on 8 July at 8:00 a.m., when a battalion advanced eastwards from Bernafay Wood and reached a small rise, where fire from German machine-guns and two field guns caused many casualties and stopped the advance, except for a bombing attack along Trônes Alley. A charge across the open was made by the survivors, who reached the wood and disappeared.[58]

The French 39th Division attacked at 10:05 a.m. and took the south end of Maltz Horn Trench, as a battalion of the 30th Division attacked from La Briqueterie and took the north end. A second attack from Bernafay Wood at 1:00 p.m. reached the south-eastern edge of Trônes Wood, despite many casualties and dug in facing north. The 30th Division attacked again at 3;00 a.m. on 9 July, after a forty-minute bombardment; the 90th Brigade on the right advanced from La Briqueterie up a sunken road, rushed Maltz Horn Farm and then bombed up Maltz Horn Trench to the Guillemont track.[59] An attack from Bernafay Wood intended for the same time was delayed, after the battalion lost direction in the rain and a gas bombardment, not advancing from the wood until 6:00 a.m. The move into Trônes Wood was nearly unopposed, the battalion reached the eastern fringe at 8:00 a.m. and sent patrols northwards. A German heavy artillery bombardment began at 12:30 p.m. from an arc between Maurepas to Bazentin-le-Grand and as a counter-attack loomed, the British withdrew at 3:00 p.m. to Bernafay Wood. The German counter-attack by the II Battalion, IR 182 from the fresh 123rd Division and parts of RIR 38 and RIR 51, was pressed from Maltz Horn Farm to the north end of the wood and reached the wood north of the Guillemont track.[60]

A British advance north from La Briqueterie at 6:40 p.m. reached the south end of the wood and dug in 60 yd (55 m) from the south-western edge. Patrols moving north in the wood found few Germans but had great difficulty getting through the undergrowth and fallen trees. At 4:00 a.m. on 10 July, the British advanced in groups of twenty, many getting lost but some reaching the northern tip of the wood, reporting it empty of Germans. To the west, bombing parties took part of Longueval Alley and more fighting occurred at Central Trench in the wood, as German troops advanced again from Guillemont, took several patrols prisoner as they occupied the wood and established posts on the western edge. By 8:00 a.m. on 10 July, all but the south-eastern part of the wood had fallen to the German counter-attack; a lull occurred as the 30th Division relieved the 90th Brigade with the 89th Brigade. The remaining British troops were withdrawn and at 2:40 a.m., a huge British bombardment fell on the wood, followed by an attack up Maltz Horn Trench at 3:27 a.m., which killed fifty German soldiers but failed to reach the objective at a strong point, after the troops mistook a fork in the trench for it.[61]

A second battalion advanced north-eastwards, veered from the eastern edge to the south-eastern fringe and tried to work northwards but was stopped by fire from the strong point. The left of the battalion entered the wood further north, took thirty prisoners and occupied part of the eastern edge, as German troops in the wood from I Battalion, RIR 106, II Battalion, IR 182 and III Battalion, RIR 51, skirmished with patrols and received reinforcements from Guillemont. Around noon more German reinforcements occupied the north end of the wood and at 6:00 p.m. the British artillery fired a barrage between Trônes Wood and Guillemont after a report from the French was received of a counter-attack by RIR 106. The German attack was cancelled but some German troops managed to get across to the wood and reinforce the garrison, as part of a British battalion advanced from the south, retook the south-eastern edge and dug in.[62] On 12 July, a new trench was dug from the east side of the wood and linked with those on the western fringe, being completed by dawn on 13 July. German attempts at 8:30 p.m. to advance into the wood were defeated by French and British artillery-fire. Rawlinson ordered XIII Corps to take the wood "at all costs" and the 30th Division, having lost 2,300 men from 7 July, was withdrawn and replaced by the 18th (Eastern) Division, the 55th Brigade taking over in the wood and trenches nearby.[63]

1918

Montauban was lost on 25 March 1918, during the retreat of the 17th (Northern) Division and the 1st Dismounted Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division during Operation Michael, the German spring offensive.[64] In the afternoon, air reconnaissance saw that the British defence of the line from Montauban and Ervillers was collapsing and the RFC squadrons in the area, made a maximum effort to disrupt the German advance.[65] The village was recaptured for the last time on 26 August, by the 18th (Eastern) Division, during the Second Battle of Bapaume.[66]

Notes

- ↑ The 8th Company had taken post near Train Alley (Kleinbahnmulde) and found itself in the path of the 30th Division; all were killed or captured and by the end of 1 July the regiment had suffered 1,809 casualties.[17]

- ↑ The official historian, James Edmonds, wrote that this was the first use of the term "creep".[22]

- ↑ The XIII Corps heavy artillery comprised three heavy artillery groups and four French mortar batteries, with howitzers: two 12-inch, eight 9.2-inch, four 8-inch, twenty-four 6-inch; guns: two 6-inch, sixteen 60-pounder, four 4.7-inch; mortars: sixteen 240 mm, which gave a heavy gun or howitzer for 47 yd (43 m) of front and a field gun or howitzer for each 17 yd (16 m)[24]

- ↑ "The Warren", a strong point opposite the 18th (Eastern) Division, had been built forward of the reserve line, from which the garrison could fire eastwards into the 30th Division area.[31]

Footnotes

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 19, 22, 24, 26, 28; Edmonds 1926, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 26, 28, 33.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Philpott 2009, p. 34; Sheldon 2006, pp. 49–50, 53.

- 1 2 Whitehead 2013, pp. 253–271.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 Wynne 1976, pp. 100–103.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, p. 160.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, p. 57.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 199.

- ↑ Duffy 2007, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 Rogers 2010, pp. 57–58.

- 1 2 3 Edmonds 1993a, p. 321.

- ↑ Jones 2018, pp. 287–288.

- 1 2 3 Edmonds 1993a, p. 344.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 130, 161–162.

- 1 2 Sheldon 2006, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 320–321.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993b, pp. 182–183.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, p. 322.

- 1 2 3 Edmonds 1993a, pp. 323–324.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, p. 324.

- 1 2 3 Rogers 2010, pp. 58–61.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, pp. 60–61; Edmonds 1993a, p. 307.

- ↑ Duffy 2007, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, pp. 61–64.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, pp. 326–327.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, pp. 327–328.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, p. 328.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 334–335.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 335–336.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 336–337, 344–345.

- 1 2 Jones 2002, pp. 213–214.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993a, p. 329.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1971, p. 82.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1971, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, p. 325.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1971, p. 126.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1971, pp. 127, 282.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 331–332.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 332–333.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 333, 338.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 338–340.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 340–341.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ Miles 1992, p. 26.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 179–180.

- 1 2 Rogers 2010, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 26–27, 5.

- ↑ Sheldon 2006, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, p. 341.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993a, pp. 320–345.

- ↑ Whitehead 2013, p. 460.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 17–23.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Miles 1992, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Edmonds 1995, pp. 473–474; Hilliard Atteridge 2003, pp. 339–342.

- ↑ Jones 2002a, p. 319.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, pp. 291–292, 299–300; Nichols 2004, pp. 376–377.

References

- Duffy, C. (2007) [2006]. Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993a) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (facs. repr. Imperial War Museum, London Department of Printed books & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993b) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme Appendices. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (facs. repr. Imperial War Museum, London Department of Printed books & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-226-5.

- Edmonds, J. E.; et al. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-219-7.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September: The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-191-6.

- Hilliard Atteridge, A. (2003) [1929]. History of the 17th (Northern) Division (repr. Naval & Military Press ed.). London: R. Maclehose. ISBN 978-1-84342-581-6.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. II. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. Vol. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Jones, H. A. (2002a) [1934]. The War in the Air Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. IV (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-415-4. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Jones, S. (2018). "XIII Corps and the Attack at Montauban, 1 July 1916". In Jones, S. (ed.). At All Costs: The British Army on the Western Front 1916. Wolverhampton Military Studies (No. 30). Warwick: Helion. pp. 270–292. ISBN 978-1-912174-88-1.

- Middlebrook, M. (1971). The First Day on the Somme. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-139071-0.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: 2nd July 1916 to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-901627-76-6.

- Nichols, G. H. F. (2004) [1922]. The 18th (Eastern) Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Blackwood. ISBN 978-1-84342-866-4.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013). The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, 1 July 1916. Vol. II. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-12-0.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Further reading

- Beach, J. (2005) [2004]. British Intelligence and the German Army 1914–1918 (PhD). London University. OCLC 500051492. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Brown, I. M. (1996). The Evolution of the British Army's Logistical and Administrative Infrastructure and its Influence on GHQ's Operational and Strategic Decision-Making on the Western Front, 1914–1918 (Thesis). London: King's College London (University of London). ISBN 978-0-275-95894-7. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10694-7.

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (PhD). London: London University. OCLC 59484941. uk.bl.ethos.367588. Retrieved 17 August 2015.