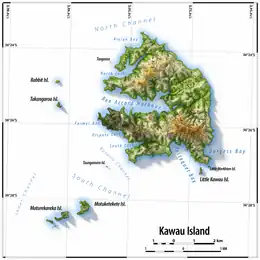

Map of Kawau Island | |

Kawau Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°25′24″S 174°50′50″E / 36.4232163°S 174.8472404°E |

| Length | 8 km (5 mi) |

| Width | 5 km (3.1 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 182 m (597 ft) |

| Highest point | Grey Heights |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 90 (June 2023)[1] |

Kawau Island is in the Hauraki Gulf, close to the north-eastern coast of the North Island of New Zealand. At its closest point it lies 1.4 km (0.87 mi) off the coast of the Northland Peninsula, just south of Tāwharanui Peninsula, and about 8 km (5.0 mi) by sea journey from Sandspit Wharf, and shelters Kawau Bay to the north-east of Warkworth. It is 40 km (25 mi) north of Auckland. Mansion House in the Kawau Island Historic Reserve is an important historic tourist attraction. Almost every property on the Island relies on direct access to the sea. There are only two short roads serving settlements at Schoolhouse Bay and South Cove, and most residents have private wharves for access to their front door steps.

The island is named after the Māori word for the shag (cormorant) bird.[2]

A regular ferry service operates to the island from Sandspit Wharf on the mainland, as do water taxi services.[3]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

The island is 8 by 5 km (5.0 by 3.1 mi) at its longest axes, and is almost bisected by the long inlet of Bon Accord Harbour which is geologically a "drowned valley".[3] The sheltered location of the bay has made it a favourite stop for yachts for more than a century.[2] The island is formed primarily by greywacke rocks an small lava flows, which formed on the seafloor before the island was uplifted by tectonic forces. Many of these lava flows were associated with hydrothermal springs, which precipitated metal sulfides and minerals rich in iron, manganese and copper.[4]

Approximately 17,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum when sea levels were over 100 metres lower than present day levels, Kawau Island was landlocked to the North Island, and surrounded by a vast coastal plain where the Hauraki Gulf exists today. Sea levels began to rise 7,000 years ago, after which Kawau became an island separated from the rest of New Zealand.[5]

History

Kawau, though providing little arable land, was well-favoured by Māori for its beautiful surrounding waters, with battles over the island common from the 17th century on.[2] Traditional stories involve the ancestor Toi-te-huatahi naming the island Te Kawau Tu Maro, meaning the shag (cormorant) standing watch.[4] Kawau was occupied for generations by Tāmaki Māori tribes including Te Kawerau and Ngāi Tai. A defensive pā, Momona, is found on the island, located in the south-west along the ridge close to modern-day Mansion House.[4]

Entrepreneurs from New South Wales purchased the island in 1840, and shortly afterwards James Forbes Beattie formed the Kawau Company, intending to mine copper on the island.[6] Miners from Falmouth, Cornwall were brought over for the operation, later joined by smelters from Wales, once it was discovered that unsmelted ore was a fire hazard for ships, and an ore smelting operation was begun on the island.[6] A rival company, funded by Frederick Whitaker and Theophilus Heale, was granted land immediately outside of the Kawau Company's land grant, giving them control of the wharf. The rival company created shafts underneath the Kawau Company's land, which led to a confrontation when miners from the Kawau Company broke into the rival company's heading.[6] In 1846 the rival company's grant was rejected, and the Kawau Company took full possession of the mines in 1848.[6] In 1844/45 the island produced about 7,000 pounds of copper, which was about a third of Auckland's exports for that year. The island was bought a few years later by Sir George Grey, Governor of New Zealand, in 1862 as a private retreat. Grey extended the original copper mine manager's house (built 1845) to create the Mansion House, which still stands, and made the surrounding land into a botanical and zoological park, importing many plants and animals.[2] The house changed hands several times after Grey, and decayed increasingly, but has been restored and furnished to its state in the period of Governor Grey and is now in public ownership in the Kawau Island Historic Reserve, administered by the New Zealand Department of Conservation.[2] The reserve is public land and covers 10% of the Island, and includes the old copper mine, believed to be the site of New Zealand's first underground metalliferous mining venture (1844).[3][7][8] The ruins of the mine's pumphouse are registered as a Category I heritage structure.[9]

The island is home to kiwi and two-thirds of the entire population of North Island weka. Among the animals that Grey introduced were five species of wallabies, as well as kookaburra.[4] Three of the six introduced wallaby species remain and do considerable damage to the native vegetation,[2] thus harming the habitat for these flightless birds and other native fauna. The wallabies destroy all emerging seedlings which means that the present native trees are the last generation. The usual understorey forest species are absent due to wallaby browsing and in many cases the ground is bare. Possums, also introduced by Grey, destroy mature native trees. The result has been a considerable loss of biodiversity, with bird numbers plummeting due to loss of both food supply and habitat. Even the surrounding marine environment has been severely compromised by silt carried from the bare ground by rainwater.

Grey's wallaby introduction however had some minor indirect benefit in the early 2000s, when species from the island were introduced into Australia's Innes National Park to boost genetic diversity.[2]

Pohutukawa Trust New Zealand

Pohutukawa Trust New Zealand was founded in 1992 by Ray Weaver and other private landowners who own 90% of the island, "to rehabilitate the native flora and fauna of Kawau Island".[10][11] Until then it was considered hopeless to reverse the considerable ecological damage caused by the introduced animal and plant species, and Kawau was said to be of historical rather than botanical importance. The Trust is a registered Charity and has run continuously since its beginnings in 1992. The Pohutukawa Trust was chaired until his death in 2015 by Ray Weaver, and is now chaired by his brother Carl. The Trust's plan is to eradicate all introduced animal pests including wallabies and possums, eradicate certain weed species and control others, and enable sustainable land uses in a restored ecological setting of native flora and fauna. The ongoing programme is funded by donations and sponsors. Possum numbers have already been greatly reduced and kept at very low numbers since 1985 through sustained control, saving the coastal pohutukawa tree, a New Zealand icon. The response to pest control work has been increasing native bird numbers, including increased kiwi calls, brown teal, kaka, kererū, and bellbirds.

After assisting with capturing all of the rare brushtail rock wallabies that could economically be recovered from the private land for relocation to a successful captive breeding programme established by Waterfall Springs Conservation Association in Wahroonga, Australia, Pohutukawa Trust New Zealand is now humanely eradicating the remaining wallabies from the island, to enable ecological restoration (mainly by natural regeneration).[12] As at 2019 four wallaby species, Tammar wallaby, Parma wallaby, Bush-tailed rock-wallaby and Swamp wallaby, all continue to threaten the native species on the island.[13]

An inventory of remaining indigenous plants and forest fragments on the island was compiled in 1996 and is being progressively enhanced to define the remnant resource still available for restoration, and several rare indigenous plant species have been discovered during the process.

Other animal pests the Trust intends to eradicate in stages as resources enable include stoats, feral cats, and ship rats. Exotic plants unpalatable to the wallabies have become serious invasive weeds on the island, and the Trust's plans include eradication or control of these also as part of the ecological restoration process.

The serious threat of possums to New Zealand's indigenous forest was first identified on Kawau by Weaver in 1955. Since then possums have become a major animal pest in New Zealand, compromising both forest health and the country's primary industries. Governor Grey introduced possums to Kawau in 1868-69. The first liberation in New Zealand is believed to have been by Captain Howell at Riverton in the South Island in 1837.

The Pohutukawa Trust New Zealand received a Green Ribbon Award from the Ministry for the Environment in 2003 "for outstanding leadership and commitment to environmental protection".

Department of Conservation controlled land

About 10% of the island is under the control of the Department of Conservation, which tries to keep the protected areas free of invasive pests and animals.[14] As at 2002, Kawau Island was home to the largest island population of North Island weka.[15]

Demographics

Kawau Island is in an SA1 statistical area which covers 21.57 km2 (8.33 sq mi)[16] and includes Motuora, Moturekareka Island, Motuketekete Island, Takangaroa Island and Rabbit Island, all of which are uninhabited. It had an estimated population of 90 as of June 2023,[1] with a population density of 4.2 people per km2. The SA1 area is part of the larger Gulf Islands statistical area.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 81 | — |

| 2013 | 78 | −0.54% |

| 2018 | 81 | +0.76% |

| Source: [17] | ||

The SA1 statistical area had a population of 81 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 3 people (3.8%) since the 2013 census, and unchanged since the 2006 census. There were 45 households, comprising 42 males and 42 females, giving a sex ratio of 1.0 males per female. The median age was 60.3 years (compared with 37.4 years nationally), with 6 people (7.4%) aged under 15 years, 3 (3.7%) aged 15 to 29, 45 (55.6%) aged 30 to 64, and 30 (37.0%) aged 65 or older.

Ethnicities were 96.3% European/Pākehā and 7.4% Māori. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.

Although some people chose not to answer the census's question about religious affiliation, 48.1% had no religion, 37.0% were Christian and 3.7% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 18 (24.0%) people had a bachelor's or higher degree, and 18 (24.0%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $24,600, compared with $31,800 nationally. 12 people (16.0%) earned over $70,000 compared to 17.2% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 24 (32.0%) people were employed full-time and 21 (28.0%) were part-time.[17]

Gulf Islands

The statistical area of Gulf Islands also includes Rangitoto Island, Motutapu Island, Browns Island, Motuihe Island and Rakino Island, but Kawau Island has the majority of the population. Gulf Islands covers 66.11 km2 (25.53 sq mi)[16] and had an estimated population of 130 as of June 2023,[18] with a population density of 2.0 people per km2.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 141 | — |

| 2013 | 120 | −2.28% |

| 2018 | 111 | −1.55% |

| Source: [19] | ||

Gulf Islands had a population of 111 at the 2018 New Zealand census, a decrease of 9 people (−7.5%) since the 2013 census, and a decrease of 30 people (−21.3%) since the 2006 census. There were 63 households, comprising 57 males and 54 females, giving a sex ratio of 1.06 males per female. The median age was 61.3 years (compared with 37.4 years nationally), with 6 people (5.4%) aged under 15 years, 3 (2.7%) aged 15 to 29, 63 (56.8%) aged 30 to 64, and 42 (37.8%) aged 65 or older.

Ethnicities were 94.6% European/Pākehā, 8.1% Māori, and 2.7% other ethnicities. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.

The percentage of people born overseas was 16.2, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people chose not to answer the census's question about religious affiliation, 48.6% had no religion, 37.8% were Christian and 2.7% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 30 (28.6%) people had a bachelor's or higher degree, and 21 (20.0%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $25,200, compared with $31,800 nationally. 18 people (17.1%) earned over $70,000 compared to 17.2% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 33 (31.4%) people were employed full-time, 24 (22.9%) were part-time, and 3 (2.9%) were unemployed.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 October 2023. (regional councils); "Subnational population estimates (TA, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 October 2023. (territorial authorities); "Subnational population estimates (urban rural), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 October 2023. (urban areas)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, Part 2". Inset to The New Zealand Herald. 3 March 2010. p. 12.

- 1 2 3 "Kawau Island: General Information". Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Cameron, Ewen; Hayward, Bruce; Murdoch, Graeme (2008). A Field Guide to Auckland: Exploring the Region's Natural and Historical Heritage (Revised ed.). Random House New Zealand. p. 296-297. ISBN 978-1-86962-1513.

- ↑ "Estuary origins". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Duder, John (2011). "Kawau Mining". In La Roche, John (ed.). Evolving Auckland: The City's Engineering Heritage. Wily Publications. pp. 278–280. ISBN 9781927167038.

- ↑ "Historic Kawau Island". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Copper smelter, Kawau Island". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Pumphouse Ruins". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Pohutukawa Trust New Zealand

- ↑ "Kawau Island wallabies". www.doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ Beston, Anne (7 December 2003). "Rare Kawau wallabies keep Aussie trappers on the hop". NZ Herald. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ J P Aley; J C Russell (December 2019). "A survey of environmental and pest management attitudes on inhabited Hauraki Gulf islands" (PDF). Science for Conservation. Department of Conservation. 336: 51. ISSN 1173-2946. Wikidata Q110606364.

- ↑ "Dog owner prosecuted over weka killing". The New Zealand Herald. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ W B Shaw; R. J. Pierce (July 2002). "Management of North Island weka and wallabies on Kawau Island" (PDF). DOC Science Internal Series. Department of Conservation. 54: 27. ISSN 1175-6519. Wikidata Q110606750. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2020.

- 1 2 "ArcGIS Web Application". statsnz.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. 7001352.

- ↑ "Population estimate tables - NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- 1 2 "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Gulf Islands (114300). 2018 Census place summary: Gulf Islands

Further reading

- Bolitho, Hector. The Island of Kawau; a record descriptive and historical, Whitcombe & Tombs, 1919.

- Russell, Roslyn (October 2001). "His island home : Sir George Grey's development of Kawau Island". National Library of Australia News. XII (1): 3–6. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.