| Casimir II the Just | |

|---|---|

| |

| High Duke of Poland | |

| Tenure | 1177–1191 1191–1194 |

| Predecessor | Mieszko III the Old |

| Successor | Leszek I the White |

| Duke of Masovia | |

| Tenure | 1186–1194 |

| Predecessor | Leszek |

| Successor | Leszek I the White |

| Born | 28 October 1138 |

| Died | 5 May 1194 (aged 55) Kraków |

| Burial | Wawel Cathedral, Kraków |

| Spouse | Helena of Znojmo |

| Issue more... | Adelaide Leszek I the White Konrad I of Masovia |

| House | Piast dynasty |

| Father | Bolesław III Wrymouth |

| Mother | Salomea of Berg |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Casimir II the Just (Polish: Kazimierz II Sprawiedliwy; 28 October 1138 – 5 May 1194) was a Lesser Polish Duke of Wiślica from 1166 to 1173, and of Sandomierz after 1173. He became ruler over the Polish Seniorate Province at Kraków and thereby High Duke of Poland in 1177; a position he held until his death, though interrupted once by his elder brother and predecessor Mieszko III the Old. In 1186 Casimir also inherited the Duchy of Masovia from his nephew Leszek, becoming the progenitor of the Masovian branch of the royal Piast dynasty, and great-grandfather of the later Polish king Władysław I the Elbow-high. The honorific title "the Just" was not contemporary and first appeared in the 16th century.

Early life

Casimir, the sixth but fourth surviving son of Bolesław III Wrymouth, Duke of Poland, by his second wife Salomea, daughter of Count Henry of Berg, was born in 1138, after his father's death but on the same day. [1] Consequently, he was not mentioned in his father's will, and thus left without any land.

During his first years, Casimir and his sister Agnes (born in 1137) lived with their mother Salomea in her widow land of Łęczyca. There, the young prince remained far away from the struggles of his brothers Bolesław IV the Curly and Mieszko III the Old with their older half-brother High Duke Władysław II, who tried to reunite all of Poland under his rule (contrary to his late father's testament) and was finally expelled in 1146.

Salomea of Berg had died in 1144. Casimir and Agnes were cared for by their elder brother Bolesław IV, who assumed the high ducal title two years later. Although under his tutelage the young prince could feel safe, he had no guarantee to receive part of the paternal inheritance in the future. When in 1151 he reached the proper age (age 13 at that time) to assume control over some of the lands of the family, he remained with nothing. Three years later (1157), his situation worsened as a result of the successful Polish campaign of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, who came to the aid of Władysław II and his sons. As a part of the treaty Bolesław IV had to conclude with Barbarossa, Casimir was sent to Germany as a hostage in order to secure the loyalty of his brother to the Emperor. The fate of Casimir at the Imperial Court is unknown. He returned to Poland certainly before 21 May 1161, because on that day he is mentioned in a document along with two of his brothers, Bolesław IV and Henry of Sandomierz.

Duke at Wiślica

In 1166, Casimir's brother Henry was killed in battle during a Prussian Crusade. He died without issue, and in his will he named Casimir the only heir of his Lesser Polish Duchy of Sandomierz. However, High Duke Bolesław IV decided to divide the duchy into three parts: the largest (which included the capital, Sandomierz) he gave to himself; a second unnamed portion he granted to Mieszko III the Old, and only the third part, the small district of Duke of Wiślica, was given to Casimir.

Angry and disappointed with the decision of the High Duke, Casimir rebelled against him, with the support of his brother Mieszko, the magnate Jaksa of Miechów, Sviatoslav son of Piotr Włostowic, Archbishop Jan of Gniezno, and Bishop Gedko of Kraków. Casimir also had the support of almost all of Lesser Poland. Quick actions by Bolesław IV stopped the rebellion, and in the end, Casimir was only able to retain Wiślica. In 1172, Mieszko III again rebelled against the High Duke, and tried to persuade his younger brother to join him. For unknown reasons, Casimir refused to participate this time.

Bolesław IV died in 1173 and according to the principle of agnatic seniority he was succeeded as High Duke by Mieszko III the Old, the oldest surviving brother. Mieszko decided to give the entire Sandomierz duchy to Casimir, and so Casimir finally assumed the ducal title that his late brother had usurped.

Revolt against Mieszko III the Old

The strong and dictatorial rule of the new High Duke caused a deep disaffection among the Lesser Polish nobility. This time a new revolt instigated in 1177 had a real chance of victory. The rebellion, apart from the magnates, counted upon the support of Gedko, Bishop of Kraków; Mieszko's eldest son Odon; Duke Bolesław I the Tall of Silesia, the son of former High Duke Władysław II; and Casimir. The reasons for his inclusion in this revolt, after being reconciled with Mieszko, are unknown.

The battle for new leadership took quite strange course: Mieszko III, completely surprised by the rebels in his Duchy of Greater Poland, withdrew to Poznań, where he stayed for almost two years enduring heavy fighting with his son Odon. Finally, he was defeated and was forced to escape. Duke Bolesław the Tall failed to conquer Kraków and the Seniorate Province, as he himself was stuck in an inner-Silesian conflict with his brother Mieszko I Tanglefoot and his own son Jarosław; soon defeated, he asked Casimir for help. After a successfully action in Silesia, Casimir marched to Kraków, which was quickly mastered. Casimir, now Duke of Kraków, decided to conclude a treaty under which Bolesław the Tall obtained full authority over Lower Silesia at Wrocław, and in return Casimir granted the Lesser Polish districts of Bytom, Oświęcim and Pszczyna to the then deposed Mieszko I Tanglefoot as a gift for Casimir's godson and namesake Casimir I of Opole, the only son of Mieszko I Tanglefoot.

High Duke of Poland

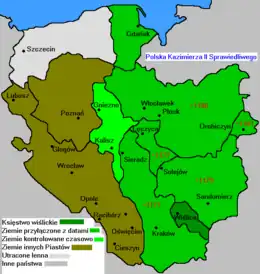

The 1177 rebellion against High Duke Mieszko III the Old was a complete success for Casimir, who not only conquered Kraków (including the districts of Sieradz and Łęczyca) obtaining the high ducal title, but also managed to extend his sovereignty as Polish monarch over Silesia (then divided between the three sons of Władysław II: Bolesław the Tall, Mieszko I Tanglefoot, and Konrad Spindleshanks, as well as Bolesław's son Jarosław of Opole), Greater Poland (ruled by Odon), and Masovia and Kuyavia (ruled by Duke Leszek, then a minor and under the tutelage of his mother and the voivode Żyrona, one of Casimir's followers). On the Baltic coast, Pomerelia (Gdańsk Pomerania) was ruled by Duke Sambor I as a Polish vassal.

Mieszko III the Old worked intensively for his return, however; at first in Bohemia and later in Germany and in the Duchy of Pomerania. In order to achieve his ambitions and give the hereditary right to the throne at Kraków (and with this the Seniorate Province) to his descendants, Casimir called an assembly of Polish nobles at Łęczyca in 1180. He granted privileges to both the nobility and the Church, lifting a tax on the profits of the clergy and relinquishing his rights over the lands of deceased bishops. By these acts, he won the acceptance of the principle of hereditary succession to Kraków, though it still would take more than a century to restore the Polish kingship.

However, in the first half of 1181 (and less than a year after the Łęczyca assembly), Mieszko III the Old, with the assistance of Duke Sambor's brother Mestwin I of Pomerelia, conquered the eastern Greater Polish lands of Gniezno and Kalisz and managed to persuade his son Odon to submit (according to some historians, Odon then received from his father the Greater Polish lands south of the Obra River). At the same time, Duke Leszek of Masovia decided to leave the influence of Casimir. He named Mieszko III the Old's son Mieszko the Younger as governor of Masovia and Kuyavia, and with this, made a tacit promise regarding the succession of these lands.

Foreign affairs

For unknown reasons, Casimir chose not to react to these events and decided only to secure his authority over Lesser Poland. A diplomatic meeting occurred in 1184 at the court of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa where Casimir, in order to block the actions of Mieszko III the Old and retain power as High Duke of Poland, swore allegiance to Barbarossa and paid him a large tribute.

The most important issues during the reign of Casimir, beside the conflicts with his brother Mieszko, were the diplomatic policies towards the neighbouring Russian principalities in the east. The first task before him as High Duke was to create bonds with the Rurik Grand Princes at Kiev, who were strongly associated with the previous High Dukes through their marriages to Kievan princesses (Bolesław IV the Curly with Viacheslava of Novgorod and Mieszko III the Old with Eudoxia of Kiev). For this purpose, in November 1178 Casimir arranged the marriage of his daughter with Prince Vsevolod IV of Kiev.[lower-alpha 1]

His first major intervention in Kievan Rus' affairs occurred in 1180, when the High Duke supported Vasylko, Prince of Shumsk and Drohiczyn (and son-in-law of the late Bolesław IV the Curly), and his nephew Leszek of Masovia in a dispute with Vladimir of Minsk for the region of Volhynia at Volodymyr. The war ended with the success of Vladimir, who conquered Volodymyr and Brest, while Vasylko held his ground at Drohiczyn.

However, this war did not definitively settle the matter of the rule at Brest, which had been granted as a fief to Prince Sviatoslav, Vasylko's cousin and Casimir's nephew (stepson of his sister Agnes). In 1182 a revolt broke out against Sviatoslav's rule, but thanks to Casimir's intervention, he was restored on the throne. Nevertheless, shortly afterwards Casimir saw that the situation was unstable, and so he finally decided to give the power to Sviatoslav's half-brother, Roman.

In 1187, Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl of Halych died, whereafter a long struggle for his succession began. Initially, the authority over the principality was taken by his younger illegitimate son, Oleg, but he was soon murdered by the boyars. Halych was then taken by Yaroslav's eldest son, Vladimirko. Vladimirko's reign was also far from stable, a situation used by Prince Roman of Brest, who, with the help of his uncle Casimir, deposed him and took full control over Halych.

The defeated Vladimirko fled to the Kingdom of Hungary under the protection of King Béla III (his relative; Vladimirko's paternal grandmother was a Hungarian princess), who decided to send his army to Halych. Roman escaped to Kraków and Vladimirko, as an act of revenge, invaded Lesser Poland. However, King Béla III soon decided to attach Halych to Hungary, and again deposed Vladimirko, replacing him as Prince of Halych with his own son, Andrew. The war continued for another two years, until Casimir restored Vladimirko's authority over Halych following instructions from Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, who had decided to help Vladimirko after he had declared himself to be his subject.

Internal politics

In 1186 Duke Leszek of Masovia died. Before his death the sickly duke decided to give all his lands to High Duke Casimir. Though Leszek had previously promised the inheritance to his elder uncle Mieszko III, his dictatorial proceedings caused Leszek to change his mind and decide in Casimir's favor. Shortly after Leszek's death however, Mieszko III occupied the lands of Kuyavia up to the Vistula River, and Casimir could only take possession over Masovia proper. Nevertheless, thanks to the Masovian inheritance, Casimir directly ruled over the major part of Poland.

The involvement of Casimir in the Russian affairs was used in 1191 by Mieszko III, who managed to take control over Wawel Castle at Kraków, seizing the high ducal title and the control over the Seniorate Province. Immediately, he declared Kraków an hereditary fief to his own descendants, implementing his son Mieszko the Younger as a governor. The conflict ended peacefully, as Casimir – upon his return from Russia – regained the capital without a fight, and Mieszko the Younger escaped to the side of his father.

The last goal of Casimir's reign was at the beginning of 1194, when he organized an expedition against the Baltic Yotvingians. The expedition ended with a full success, and Casimir had a triumphant return to Kraków. After a banquet was held to celebrate his return, Casimir died unexpectedly, on 5 May 1194. Some historians believed that he was poisoned. He was succeeded as High Duke by his eldest surviving son Leszek I the White, who like his father had to face the strong opposition from Mieszko III the Old. Casimir was probably buried at Wawel Cathedral.[1]

Casimir had planned to found a university in Kraków and already started to construct the building, but his sudden death balked his plans. The present-day Jagiellonian University was not established until 1364 by King Casimir III the Great as the second oldest in Central and Eastern Europe (after the Charles University in Prague).

Relations with the Church

During his reign, Casimir was very generous to the Church, especially with the Cistercians monasteries of Wąchock, Jędrzejów, Koprzywnica and Sulejów; with the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre of Miechów, Regular Canonry of Czerwińsk nad Wisłą and Trzemeszno and the Order of the Knights Hospitaller in Zagość. He also tried to expand the cult of Saint Florian, whose remains were brought to Kraków by Bishop Gedko.

Marriage and issue

Between 1160 and 1165 (but no later than 1166[2]), Casimir married with Helena (ca. 1140/42 – ca. 1202/06), daughter of Duke Conrad II of Znojmo, scion of a Moravian cadet branch of the Přemyslid dynasty. They had:

- Maria (renamed Anastasia after her marriage[lower-alpha 2]) (b. before 1167), married between 11 October and 24 December 1178 to Prince Vsevolod IV of Kiev.[3]

- Casimir (ca. 1162 – 2 February[4] or 1 March 1167), named after his father.

- Bolesław (ca. 1168/71 – 16 April 1182/83), probably named after his paternal grandfather Bolesław III Wrymouth, although it is possible that he was named in honour of his uncle Bolesław IV the Curly.[5] He died accidentally, after falling from a tree. He was probably buried at Wawel Cathedral.[6]

- Odon (1169/84 – died in infancy). He was probably named after either Odon of Poznań or Saint Odo of Cluny.[7][8]

- Adelaide (ca. 1177/84 – 8 December 1211), foundress of the convent of St. Jakob in Sandomierz.

- Leszek I the White (ca. 1184/85 – 24 November 1227)[9]

- Konrad (ca. 1187/88– 31 August 1247)[10]

Notes

- ↑ This daughter might have been named Maria, changing her name to Anastasia after the marriage. Through Maria's great-granddaughter Kunigunda of Slavonia, Casimir was a direct ancestor of the last Přemyslid Kings of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Emperors of the Luxembourg dynasty.

- ↑ This daughter might have been named Maria, changing her name to Anastasia after the marriage. Through Maria's great-granddaughter Kunigunda of Slavonia, Casimir was a direct ancestor of the last Přemyslid Kings of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Emperors of the Luxembourg dynasty.

References

- 1 2 Jasiński 2004, p. 265.

- ↑ Jasiński 2004, p. 267.

- ↑ Dobosz 2014, p. 267.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 247.

- ↑ Pelczar 2013, p. 62-64.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 23-25.

- ↑ Jasiński 2001, p. 30-32.

Bibliography

- Dobosz, Józef (2014). Kazimierz II Sprawiedliwy. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie. p. 267. ISBN 978-83-7177-893-3.

- Jasiński, K. (2001). Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich. Poznań–Wrocław.

- Jasiński, K. (2004). Rodowód pierwszych Piastów. Poznań.

- Pelczar, S. (2013). Władysław Odonic. Książę wielkopolski, wygnaniec i protektor Kościoła (ok. 1193-1239). Editorial Avalon, Kraków.