| Western Desert | |

|---|---|

| Wati | |

| Native to | Australia |

| Region | Desert areas of Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory |

| Ethnicity | Western Desert cultural bloc |

Native speakers | 7,400 (2006 census)[1] |

Pama–Nyungan

| |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Western Desert Sign Language Manjiljarra Sign Language Ngada Sign Language | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:ktd – Kokata (Kukarta)kux – Kukatjampj – Martu Wangkantj – Ngaanyatjarrapti – Pintiini (Wangkatja)piu – Pintupi-Luritjapjt – Pitjantjatjaratjp – Tjupanykdd – Yankunytjatjara |

| Glottolog | wati1241 Wati |

| AIATSIS[1] | A80 |

| ELP | Kukatja |

| Pintiini[4] | |

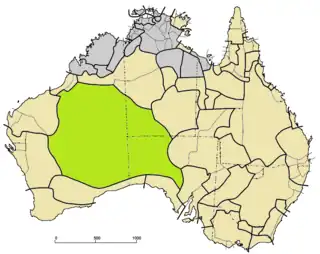

Wati languages (green) among Pama–Nyungan (tan) | |

The Western Desert language, or Wati, is a dialect cluster of Australian Aboriginal languages in the Pama–Nyungan family.

The name Wati tends to be used when considering the various varieties to be distinct languages, Western Desert when considering them dialects of a single language, or Wati as Wanman plus the Western Desert cluster.

Location and list of communities

The speakers of the various dialects of the Western Desert Language traditionally lived across much of the desert areas of Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Most Western Desert people live in communities on or close to their traditional lands, although some now live in one of the towns fringing the desert area such as Kalgoorlie, Laverton, Alice Springs, Port Augusta, Meekatharra, Halls Creek and Fitzroy Crossing.

The following is a partial list of Western Desert communities:

- Kintore, Northern Territory

- Docker River, Northern Territory

- Ernabella, South Australia

- Amata, South Australia

- Fregon, South Australia

- Pipalyatjara, South Australia

- Kalka, South Australia

- Warburton, Western Australia

- Kiwirrkurra, Western Australia

- Balgo, Western Australia

- Aputula, Northern Territory (also known as Finke)

- Imanpa, Northern Territory (also known as Mount Ebenezer)

- Mutitjulu, Northern Territory

- Jigalong, Western Australia

Dialect continuum

The Western Desert Language consists of a network of closely related dialects; the names of some of these have become quite well known (such as Pitjantjatjara) and they are often referred to as "languages".[5] As the whole group of dialects that constitutes the language does not have its own name it is usually referred to as the Western Desert Language. WDL speakers referring to the overall language use various terms including wangka ("language") or wangka yuti ("clear speech"). For native speakers, the language is mutually intelligible across its entire range.

Dialects

Following are some of the named varieties of the Western Desert Language, with their approximate locations. Starred names are listed as separate languages in Bowern (2011 [2012]).

- Antakarinya (Antakirinya)* – north-east of SA

- Kartutjarra* – Kartudjara people, near Jigalong, WA

- Kukatja* (Ŋatatara) – Yumu and Gugadja people, near Balgo, WA (see also below - 2 with same name)

- Kokatha* – Kokatha Mula people, central SA

- Luritja – Kukatja/Loritja people, central Australia

- Manyjilyjarra (Manjiljarra)* – Mandjildjara (and Mandjindja?) people, near Jigalong

- Martu Wangka – Jigalong Community

- Ngaanyatjarra* – near Warburton, WA

- Ngaatjatjarra – near Warburton, WA

- Ngalia/Ngaliya (Ooldean) – Salt Lake districts in Western (or Great Victoria) Desert northwest of Ooldea (spoken by the Ngalia people[6])

- Pintupi* – Kintore (Northern Territory) and further west.

- Pintupi Luritja – Papunya and Kintore region, NT

- Pitjantjatjara* – North-west of SA

- Putijarra* – Putijarra people, south of Jigalong, WA

- Titjikala Luritja* – Titjikala, around Maryvale and Finke, NT

- Tjupany* – Madoidja people/region?

- Wangkatjunga (Wangkajunga)* – south of Christmas Creek, WA (part of Martu Wangka?)

- Watha – east of Meekatharra, WA

- Wawula – Wardal people? Madoidja people?, south-east of Meekatharra

- Wonggayi – Pindiini/Wangkatha people, Kalgoorlie to Cosmo Newberry and Wiluna region, W.A

- Yankunytjatjara* – north-west of SA

- Yulparirra (Yulparija)* – north of Jigalong

Other names associated with Western Desert though they may not be distinct varieties include Dargudi (Targudi), Djalgandi (Djalgadjara), Kiyajarra (Giyadjara, Keiadjara), Nakako, Nana (Nganawongka), Waljen, Wirdinya, and perhaps Mudalga.

The Nyiyaparli language is no longer classified as Wati.

There is considerable variation across this region given the size of the area.

Kukatja

As of 2019, scientists from the University of Queensland have been undertaking a research project on the Kukatja language in Balgo, the local lingua franca which is fluently spoken "by residents of all ages and across at least seven tribal groups". Researchers are recording conversations and mapping the language, believing that Kukatja could provide clues to how languages are spread around the world. Dr Luis Miguel Rojas Berscia believes that the mission, as in other places such as the Amazon and West Africa could be the common thread, bringing different ethnic groups together in isolated spots. Berscia, along with Balgo woman Melissa Sunfly and other residents, is working on developing a dictionary of the language and a teacher's guide, before English is taken up more widely by the younger generation.[7]

As of 2020, AIATSIS distinguishes two Western Desert dialects with the same name: A68: Kukatja[8] and C7: Kukatja.[9]

Language

Status

The Western Desert Language has thousands of speakers, making it one of the strongest indigenous Australian languages. The language is still being transmitted to children and has substantial amounts of literature, particularly in the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara dialects in South Australia where there was formerly a long-running bilingual program.

Phonology

In the following tables of the WDL sound system, symbols in ⟨angle brackets⟩ give a typical practical orthography used by many WDL communities. Further details of orthographies in use in different areas are given below. Phonetic values in IPA are shown in [square brackets].

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ iː ⟨ii⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ uː ⟨uu⟩ |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ aː ⟨aa⟩ | |

The Western Desert Language has the common (for Australia) three-vowel system with a length distinction creating a total of six possible vowels.

Consonants

| Peripheral | Laminal | Apical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Velar | Palatal | Alveolar | Retroflex | |

| Plosive | p ⟨p⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | c ⟨tj⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | ʈ ⟨rt⟩ |

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ɲ ⟨ny⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɳ ⟨rn⟩ |

| Trill | r ⟨rr⟩ | ||||

| Lateral | ʎ ⟨ly⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | ɭ ⟨rl⟩ | ||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | ɻ ⟨r⟩ | ||

As shown in the chart, the WDL distinguishes five positions of articulation, and has oral and nasal occlusives at each position. The stops have no phonemic voice distinction but display voiced and unvoiced allophones; stops are usually unvoiced at the beginning of a word, and voiced elsewhere. In both positions, they are usually unaspirated. There are no fricative consonants.

Orthography

While the dialects of the WDL have very similar phonologies there are several different orthographies in use, resulting from the preferences of the different early researchers as well as the fact that the WDL region extends into three states (Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory), with each having its own history of language research and educational policy.

Sign language

Most of the peoples of central Australia have (or at one point had) signed forms of their languages. Among the Western Desert peoples, sign language has been reported specifically for Kardutjara and Yurira Watjalku,[10] Ngaatjatjarra (Ngada),[11] and Manjiljarra. Signed Kardutjara and Yurira Watjalku are known to have been well-developed, though it is not clear from records that signed Ngada and Manjiljarra were.[12]

References

- 1 2 A80 Western Desert at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ C2 Ngalia at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge University Press. p. xxxvii.

- ↑ Endangered Languages Project data for Pintiini.

- ↑ "Pitjantjatjara language, alphabet and pronunciation". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ↑ C2 Ngalia at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ Bamford, Matt (28 December 2019). "Researchers map ancient language in West Australian outback". ABC News (ABC Kimberley). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ A68 Kukatja at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ C7 Kukatja at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ↑ Miller, Wick R. (1978). A report on the sign language of the Western Desert (Australia). Reprinted in Aboriginal sign languages of the Americas and Australia. New York: Plenum Press, 1978, vol. 2, pp. 435–440.

- ↑ C.P. Mountford (1938) "Gesture language of the Ngada tribe of the Warburton Ranges, Western Australia", Oceania 9: 152–155. Reprinted in Aboriginal sign languages of the Americas and Australia. New York: Plenum Press, 1978, vol. 2, pp. 393–396.

- ↑ Kendon, A. (1988) Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goddard, C. 1985. A Grammar of Yankunytjatjara. Alice Springs: IAD.

- Rose, David (2001), The Western Desert Code: an Australian cryptogrammar, Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, ISBN 085883-437-5