| Operation Arctic Fox | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Silver Fox | |||||||

A column from Panzerabteilung 40 during the advance on the Murmansk railway, 1941. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

XXXVI Corps: 9,463 men[2] III Corps: unknown[note] | Heavy casualties | ||||||

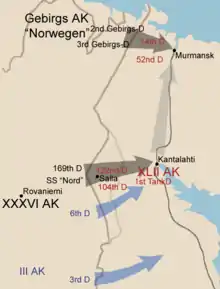

Operation Arctic Fox (German: Unternehmen Polarfuchs; Finnish: operaatio Napakettu; Russian: Кандалакшская операция)[a] was the codename given to a World War II campaign by German and Finnish forces against Soviet Northern Front defenses at Salla, Finland in July 1941. The operation was part of the larger Operation Silver Fox (Silberfuchs; Hopeakettu) which aimed to capture the vital port of Murmansk. Arctic Fox was conducted in parallel to Operation Platinum Fox (Platinfuchs; Platinakettu) in the far north of Lappland. The principal goal of Operation Arctic Fox was to capture the town of Salla and then to advance in the direction of Kandalaksha (Finnish: Kantalahti) to block the railway route to Murmansk.

As a joint operation by German and Finnish forces, it combined experienced Finnish arctic troops with relatively unsuitable German forces from Norway. They managed to capture Salla after fierce fighting, but the German troops were unable to overcome the old, pre-war Soviet border fortifications further east. The Finnish units were able to make better progress, and came to within 30 km (19 mi) of the Murmansk railway. Strong Soviet reinforcements prevented any further advance. Because of the escalating situation further south in Central Russia, the Germans were unwilling to assign more units to this theatre, calling an end to their offensive. With the Finns unwilling to continue the attack on their own, Arctic Fox ended in November 1941, when both sides dug in at their current positions.

Background

The German High Command (OKW) included Finland in its plan for its major offensive against the Soviet Union: Operation Barbarossa. A joint Finnish-German offensive named Operation Silver Fox was planned to support the Germany's main effort in central Russia. The goal of Silver Fox was to capture or disable the port of Murmansk, which was to be a major destination for Western Allied shipping aid to the Soviet Union, by executing a pincer attack against it.[3][4] The southern pincer of the attack was named Operation Arctic Fox and was launched from the Kemijärvi region of Central Finland against the defenses at Salla. [5]

Salla was occupied by the Soviets during the invasion of Finland in 1939. German XXXVI Corps, consisting of both German and Finnish troops, was the main German force of the operation. The corps was commanded by General Hans Feige and was subordinate to the Army of Norway which was commanded by Nikolaus von Falkenhorst. XXXVI Corps was supported by Finnish III Corps commanded by Hjalmar Siilasvuo.[3][6]

Planning and Preparation

Planning for the operation started in December 1940. Erich Buschenhagen, chief of staff of Army of Norway, visited Finland and drew up a plan which would determine Finland's role in the war, including the first draft of German-Finnish joint operations against the Soviet Union. On 8 December 1940 Hitler issued Directive No. 21, which detailed his plan for Operation Barbarossa as whole and included the targets for proposed German-Finnish cooperation. The detailed operational plan was created by Nikolaus von Falkenhorst with Army of Norway staff in January 1941.[7][8]

German units assigned to the operation were transported to the Arctic in successive operations Blue Fox 1 and Blue Fox 2. The 169th Division and Feige's headquarters were transported by ship and train to Rovaniemi. From there they joined Finnish forces and took position for the offensive under the guise of border exercises. The SS-Infantry Kampfgruppe Nord was created, consisting of the 6th and 7th Motorized SS Infantry Regiments, two artillery battalions, and one reconnaissance battalion. This unit was primarily an untrained police unit and unsuited for arctic warfare. During transit from Norway to Finland a transport ship caught fire and 110 soldiers died. [9] The unit was renamed the 6th SS Mountain Division Nord and was led by General Demelhuber. Two small Panzer units were attached to the force: Panzer-Abteilung 211 which used captured French tanks (Hotchkiss H39), and Panzer-Abteilung 40 which consisted mainly of Panzer I and Panzer II (and a small reinforcement of Panzer III) tanks.[10]

The goal of the operation was to take Salla, and then to proceed eastward along the railway to capture Kandalaksha, and to cut the Murmansk Railway line which connected Murmansk with Russia. To accomplish this, the German-Finnish forces advanced in two main groups: one led by the XXXVI Corps in the north, and one by the Finnish III Corps in the south. For XXXVI Corps part, the 169th Division advanced in a three-pronged, frontal attack against the defense line along the Tenniö River. Further south the Finnish 6th Division attempted a flanking operation into the Soviet rear from Kuusamo. They had to advance through difficult terrain to the northeast and capture the towns of Alakurtti and Kayraly (Kairala). Finnish III Corps was placed under the command of Army High Command Norway for the operation. There they would meet up with the German divisions. Both divisions were supported by the 6th SS Mountain Division that advanced in the centre along the Salla – Kandalaksha road in a frontal assault against the defensive line.[6][11][12]

Further south, the Finnish 3rd Division launched an attack, the goal being to cut the Murmansk supply-lines at Loukhi and Kem. For this the 3rd Division was split into two battlegroups. Group J advanced from south of Kuusamo to take Kestenga (Kiestinki), while Group F attacked from Suomussalmi to capture Ukhta.[6][11]

Aerial support for the offensive was provided by Luftflotte 5 and the Finnish Air Force. The Luftwaffe created a new headquarters for the operation and moved it into Finland. The Finnish air force fielded about 230 aircraft of various types. Luftflotte 5 assigned 60 planes to Silver Fox and used Junkers Ju 87, Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111 aircraft for ground support.[6][13][14]

The Soviets were less prepared. While they anticipated a German invasion, with possible Finnish support, Stalin did not expect an attack along the entire border so early. The border was heavily fortified, but Soviet leadership was unprepared for the German attack. The formation opposing Silver Fox was the Northern Front, consisting of the 7th and 14th Armies. They were commanded by Lieutenant-General Markian Popov. On 23 August 1941, the Northern Front was split up into the Karelian Front and the Leningrad Front, commanded by Valerian Frolov and Popov.[15] Frolov remained in command of the Karelian Front until 1 September, when he was promoted and replaced by Roman Panin. During the first weeks the Axis would have a numerical superiority, as the Soviets only had 150,000 men north of Lake Ladoga along the border.[16][17]

The Axis had air superiority as Soviet Karelia was protected by the 1st and 55th Mixed Air Divisions, totaling 273 aircraft, many outclassed by their enemy.[18] This situation was partly alleviated by the reinforcement of No. 151 Wing RAF on September 7, 1941 at Vaenga airfield. The Wing was tasked with providing Hawker Hurricane aircraft and training for the Russians, but also flew 365 sorties over the Murmansk area, accounting for 14 German aircraft kills.

Operation Arctic Fox

Start of the war

On September 1, 1940, Finland signed a treaty allowing the Germans to transit troops through Finland to Norway.[19] During German-Finnish negotiations the Finnish High Command offered its support to the German "venture", but the Finnish national parliament sanctioned military action against the Soviets only in case the Soviet Union attacked them first.[note][20] On 22 June Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, invading the Soviet Union. German aircraft used Finnish air bases, and the army launched Operation Reindeer which captured Petsamo. Simultaneously Finland remilitarized the neutral Åland Islands. Despite these actions the Finnish government insisted it was neutral, but the Soviet leadership already viewed Finland as Germany's ally. The Murmansk Oblast declared a state of emergency, mobilizing 50,000 soldiers and sailors. Conscripts and volunteers joined the newly formed 1st Polar Rifle Division, while sailors from the Northern Fleet enlisted in a marine infantry brigade. Civilians were also employed in the construction of four lines of fortifications, between Zapadnaya Litsa and Kola Bay. The Soviets proceeded to launch an air raid on 25 June, bombing all major Finnish cities and industrial centers including Helsinki, Turku and Lahti. During a night session, the Finnish parliament voted to go to war against the Soviet Union and Operation Arctic Fox would begin within a week.[21][22][23][24][25]

Capture of Salla and stalemate at Kayraly

Arctic Fox began at midnight 1 July 1941, when the Finnish 6th Division crossed the border. The 6th SS Mountain Division Nord and the 169th Division attacked the Soviets several hours later. Soviet positions were heavily fortified and manned by divisions from the Soviet 14th Army: the 122nd Rifle Division, the 104th Rifle Division, and the 1st Tank Division commanded by Valerian A. Frolov. In daylight, facing Soviet resistance, both divisions sustained heavy losses and the attack failed,[1][6][26] with SS Nord Division faring especially badly. The situation worsened the next day when, after a renewed assault, the Soviets counterattacked. SS Nord staff panicked and some of the division routed, forcing Feige and the XXXVI Corps command to intervene to restore order.[27]

This failure prompted the German command to rethink its strategy. To reinforce the troops and replace the losses, additional personnel were transferred from the 163rd Infantry Division based in Southern Finland. With a combined effort by all the German forces, extensive air-support by Luftflotte 5, as well as a supportive flanking attack by the Finnish 6th Division, they finally broke through the Soviet defenses on 6 July and captured Salla. A heavy Soviet counterattack drove them back out of the town but on 8 July, a general Soviet retreat of the 122nd Rifle Division allowed the German forces to recapture the town. The Soviet troops had to leave most of their artillery behind and in the heavy fighting some 50 Soviet tanks were destroyed.[11][28] In order not to lose momentum, the SS Division Nord pursued the 122nd Rifle Division toward Lampela, while the 169th Division turned east toward Kayraly. Meanwhile, the Finnish 6th Division was making good progress in its flanking manoeuvre to the east to circumvent Kayraly and Lape Apa.[29]

On 9 July, the 169th Division reached the town of Kayraly, but was thrown back by strong Soviet counterattacks. All three Soviet divisions now formed a formidable defense line around Kayraly, incorporating the adjacent lakes Apa and Kuola into their defense. The German advance stalled, facing difficulties with arctic forest fighting. At the same time the Soviets managed to bring additional reinforcements to replace their losses. On 16 July, Falkenhorst arrived at the XXXVI Corps' headquarters and pressured Feige to renew the offensive. Feige relented and on 27 and 29 July the corps made two additional attacks separately against the Soviets which led to nothing.[28][30] A stalemate had developed at the front line that the Germans could not break. Due to the grim situation, and mounting losses (5,500 men in just one month), AOK Norwegen finally ordered Feige to halt the offensive.[31]

Attack of the Finnish III Corps

While the German advance stalled, the Finnish 3rd Division of III Corps in the south was making good progress. The division's first opponent was the Soviet 54th Rifle Division of the Soviet 7th Army. Group F advanced very quickly through 64 km (40 mi) of rough terrain to the Vyonitsa River, where it encircled and destroyed several Soviet units from 10 to 19 July. Group J advanced to the strongly defended canal between Lake Pyaozero and Lake Topozero. Astonished by the rapid Finnish success, the AOK Norwegen now decided to support the Finnish advance by transferring parts of the SS Nord Division south and put them under Finnish command.[32][33]

Beginning on 30 July, the Finns succeeded in smuggling a battalion over the lakes, behind Soviet lines, which allowed them to flank and subsequently defeat the Soviets on the other side of the canal. On 7 August, the Finns captured Kestenga after fierce fighting. Reacting to the Finnish advance on the Murmansk railway, the Soviets transferred additional troops (the 88th Rifle Division as well as the independent Grivnik brigade) into the region. Soviet resistance now stiffened, leading to a stall of Group J's advance east of Kestenga.[32][33] While Group J had been embroiled in the battle around Kestenga, Group F was able to reach the outskirts of Ukhta. They broke through the defense line at the Yeldanka Lake, and were able to come within a few miles short of Ukhta proper. However, the new Soviet reinforcements prevented any further gains, and the Finnish attack stalled in this sector too.[34]

With the increasing Soviet resistance, a plan was made to concentrate on only one target. It was decided to halt the Ukhta-offensive and instead support the advance east of Kestenga in mid-August. This new drive was able to make some ground in the arctic no-man's land, but no decisive breakthrough could be achieved. The increasing Soviet activity also worried Siilasvuo, especially as Group F was now standing still in exposed terrain, open to a possible Soviet encirclement. To counter this, AOK Norwegen decided to bolster the Finnish forces for a final push to the east and the rest of the SS Nord division was moved south and put under Finnish command. Also parts of 6th Finnish Division were now moved south and returned to the Finnish III Corps for more reinforcements. Once the reorganisation had been completed, a new, final attack had to be launched by both Finnish battlegroups in October.[32][33][35]

Concurrently to these advances, a Finnish jaeger (jääkäri) battalion was inserted into the largely unoccupied 240 km (150 mi) area between the Murmansk and Kandalaksha directions of the advance and was able to cut the sole railway line connecting Kandalaksha with forward Soviet positions at the Nyam station. This meant that for two weeks the Soviet 122nd Rifle Division did not receive any supplies and had to live off its field dumps.[1]

Renewed attack in the centre toward the Murmansk Railway

During the successful advance by Finnish forces in the south, tensions between the headquarters of XXXVI Corps and AOK Norwegen rose. Feige naturally believed that his corps should lead the main effort against the Murmansk railway. However, instead of giving him the requested reinforcements to overcome the strong Soviet defenses and reach the goal of Kandalaksha, Falkenhorst was transferring more and more units south to bolster the Finnish III Corps' advance. While AOK Norwegen indeed saw the greatest chance of success within III Corps, nevertheless it ordered Feige to resume his offensive towards the east, leaving him in a very difficult situation.[36]

With no other choices left, Feige drew up a plan for another offensive. The thinly stretched forces of the 169th division had to split up to take over the defense line along the entire frontline between Kayrala and its adjacent lakes. The Finnish 6th Division would then be freed to undertake another massive flanking operation. Coming from the very south, they would circumvent the Soviet positions at Kayrala and thrust to a position east of it behind the Soviet lines at Lake Nurmi. The 169th Division would do the same, but from the north, resulting in a large pincer movement to trap the Soviets.[37] At the beginning of August 1941 this plan was launched with the Finnish 6th Division heading the renewed drive of the XXXVI Corps with the 169th Division following. The plan met with unexpected success. The attack completely surprised the Soviets and a large firefight developed around Kayraly. The German-Finnish force was able to encircle large parts of the Soviet 42nd Rifle Corps and its 104th Division. Although some units escaped, large Soviet formations were subsequently destroyed and the Soviets had to leave most of their equipment behind.[37][33][38] In the face of the new German thrust, the Soviets retreated to the Tuutsa River. They tried to establish a new defensive line around Alakurtti, but were unable to hold out against the pursuing Finnish-German units. After the Soviets lost Alakurtti they withdrew to the Voyta River where the old 1939 Soviet border fortifications were situated.[38][39]

On 6 September, XXXVI Corps launched a frontal assault against the Soviet fortifications but made only slow progress. XXXVI Corps attempted another flanking attack similar to Kayrela, with one German regiment trying to circumvent the Soviet defenses in the south. This time it did not work as well, and the German effort bogged down against heavy resistance. After days of fighting, the Germans were finally able to push behind the Voyta River only to be confronted by another even stronger Soviet defense line. The so-called VL or Verman Line stretched from Lake Verkhneye Verman to Lake Tolvand and included heavy Soviet pre-war fortifications.[40]

By this point XXXVI Corps had reached total exhaustion. With the transfer of the SS Division Nord to the south, and a return of the Finnish 6th Division to III Corps, Feige deemed any further advance in this sector impossible. With the Soviets bringing more reinforcements to the front every day, Feige requested more men if he was to start a new attack. Plans were made by AOK Norwegen for a resumption of the offensive, but the German High Command was unable to reinforce the Arctic theatre with additional units and AOK Norwegen could not send anything meaningful itself to aid Feige. Consequently, all offensive plans were scrapped. Due to the more spectacular gains at the main front in Central Russia during Operation Barbarossa, the OKW deemed the current situation acceptable and an end was ordered to the offensive operations of XXXVI Corps. This, combined with heavy German casualties, led to the attack finally being called off at the end of September.[38][39]

Final battles of III Corps and the end of the operation

While XXXVI Corps was struggling against the Soviets, III Corps' situation was not much better, despite reinforcements arriving from the transfers of XXXVI Corps to the south. Group F's new drive on Ukhta was immediately stopped in its tracks by recent reinforcements of the 88th Rifle Division. The Soviets now launched a heavy counterattack. The Finns, who were still reorganising with the recently arrived German units for a revived push to the east, were forced to retire. To counter the new threat AOK Norwegen now threw in everything it had available to bolster the Finnish front. New assignments included another regiment from XXXVI Corps as well as parts of the 14th Finnish Infantry Regiment pulled from Operation Platinum Fox, the German front in the far north. The new reinforcements helped to stabilise the front.[41]

Finally, on 30 October, the new long-planned offensive began, and after two days a Soviet regiment was encircled. Finnish General Hjalmar Siilasvuo proceeded to clear the perimeter with his troops. After the disappointing performance of the SS units under his command and the realization that he neither the Finnish nor the German high command is going to provide him with additional forces or substantial reinforcements, he slowed down the advance towards the east and instead concentrated on clearing and securing the area. Those mop-up operations were completed by 13 November. By that point the Finnish 3rd Division had killed 3,000 Soviet soldiers and captured 2,600.[32][33][42]

With the Germans mostly unable to operate and advance without the support of the experienced Finnish units, their hope now lay on a continuation of the attack led by the Finns themselves. These hopes were soon squashed. Field Marshal Carl Mannerheim, supreme commander of the Finnish forces, insisted on delaying further offensive operations, citing military and logistical reasons. On 17 November, Siilasvuo ordered an immediate stop to the Finnish III Corps' offensive, despite positive feedback from his field commanders that further ground could be taken. This sudden change in Finnish behaviour was, in some part, the result of diplomatic pressure by the United States and Britain.[note] Finland was no longer interested in spearheading such an offensive. With the Finnish refusal to be involved in further offensive operations, Arctic Fox came to an end in November and both sides dug in.[43][44]

Aftermath

Operation Arctic Fox did not meet its goals. During the operation the German and Finnish forces took Salla as well as Kestenga, but overall the operation failed in terms of its strategic intentions, as neither Murmansk nor the Murmansk railway at Kandalaksha were captured. The closest the German-Finnish force came to the Murmansk railway was east of Kestenga, where they were about 30 km (19 mi) away from it. The XXXVI Corps, especially its SS-component, was ill-trained and unprepared for arctic warfare and therefore made little progress while suffering heavy casualties. On the other hand, the Finnish units, especially the 6th Division of the III Finnish Corps, made good progress and inflicted heavy casualties on the Soviet forces.[43][44]

The failure of Arctic Fox had a significant impact on the course of the war in the east. Murmansk was a major base for the Soviet Northern Fleet and it was also together with Arkhangelsk the main destination for Allied aid shipped to the Soviet Union. British convoys had traveled to Murmansk since the summer at the onset of the war, but with the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, the influx of Western Allied aid increased massively. The United States enacted the Lend-Lease pact in which they vowed to supply the Soviet Union with large quantities amounts of food, oil, and war materiel. One quarter of this aid was delivered via Murmansk. This included large amounts of raw materials like aluminum as well as large quantities of military goods for the Soviet war effort, including 5,218 tanks, 7,411 aircraft, 4,932 anti-tank guns, 473 million rounds of ammunition and various sea vessels. Those supplies benefited the Soviets significantly and contributed to their continued resistance.[45][46][47]

For the remainder of the war the Arctic front remained stale. The German High Command did not regard it as an important theatre and therefore refrained from transferring the substantial reinforcements needed for a renewal of the offensive. The Finns likewise were not interested in continuing the offensive on their own as they did not want to antagonize the Western Allies further. In September 1944, following a series of devastating German defeats, the Finns sued for peace with the Soviet Union and had to give up all their territorial conquests. The Germans subsequently retreated from Central Finland to Petsamo and Norway. In October 1944, the Red Army conducted the Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation and achieved a decisive victory over the German forces in the Arctic by completely expelling them from Finland.[48][49]

Notes

- a Russian historiography commonly describes the fighting in this area as the Kandalaksha Operation.[25]

- b A mixed unit consisting of ad hoc drafted and volunteered sailors,[45] later renamed 186th Rifle Division. In November, it was transferred to the south of Murmansk when Operation Platinum Fox slowed down.[50]

- c The Finns suffered around 5,000 casualties during the course of the whole Silver Fox operation.[2]

- d The matter of when and why Finland prepared for war is still somewhat opaque. See: William Trotter A Frozen Hell Algonquin Books, 1991, p. 226

Despite exhaustive efforts by Finnish historians, it is so far proven impossible to pinpoint the exact date on which Finland was taken into confidence about Operation Barbarossa. The "paper trail" is tantalizing but leads only to dead ends and side paths, not to any benchmark conference or dates. Probably no formal agreements were necessary. The Finnish Generals who were privy to joint planning were mostly German trained and intimately familiar with the German way of waging war. There was also a certain amount of coyness on both sides. Joint operations were discussed, all during the spring of 1941, in purely hypothetical terms, and neither the Finns nor the Germans were entirely candid with one another as to their national aims and methods. In any case, the step from contingency planning to actual operations, when it came, was little more than a formality. Three days after the start of Barbarossa, Stalin handed the Finns a perfect excuse by launching some air raids. War was declared on June 25, 1941

- e See Gerhard Weinberg A World at Arms Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 271:

A political factor also restrained the Finns as they approached the border they had before the Russian attack of 1939. They came under increasing pressure from Britain and the United States to stop at the old border. There were element within Finland which favoured such a halt; and in their hour of peril in October–November 1941, the Soviet Union through the United States offered to return to that border if Finland made peace. The euphoria caused by the same German victories which produced this Soviet offer misled the Finns into disregarding it and continuing in the war for expansionist objectives in eastern Karelia and in the far north. The British thereupon declared war on Finland, while, in fear that the United States would do the same, refrained from even further offensives.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Shirokorad (2001), pp. 708–720.

- 1 2 Ziemke (1959), pp. 176, 184.

- 1 2 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 69.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Ueberschär (1998), pp. 945.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ueberschär (1998), pp. 945–946, 950.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 87.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 55, 89.

- 1 2 3 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 88.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), p. 180.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 131, 137–138.

- ↑ Shirokorad (2001), pp. 709–710.

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), pp. 47–48, 53.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 76–77.

- ↑ Inozemtzev (1975), pp. 4–10.

- ↑ Keegan, John The Second World War Penguin, 2005, p.136

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), p. 36 ""Following these negotiations, the Finnish national parliament decided to sanction military action against the Soviet Union, but only if the Red Army attacked first. Otherwise, Finland was to remain strictly neutral" AND "In June, the following demands for Finnish participation (in Operation Barbarossa) were presented: Finland would remain independent, Germany would have to attack first and Finland would only join the fighting after the Soviet Union had initiated the hostilities".

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), pp. 36, 39–41.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Inozemtzev (1975), pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Kiselev (1988), pp. 69–81.

- 1 2 Shirokorad (2001), pp. 710–713.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 89.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 159–161.

- 1 2 Ueberschär (1998), pp. 941–942.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), p. 163.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), p. 90.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 3 4 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 90–93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ueberschär (1998), pp. 950–951.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 168–170.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 170–171.

- 1 2 Ziemke (1959), pp. 171–172.

- 1 2 3 Ueberschär (1998), pp. 942–943, 951.

- 1 2 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 172–176.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), pp. 62–63.

- 1 2 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 93–97.

- 1 2 Ueberschär (1998), pp. 949–953.

- 1 2 Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 81–87.

- ↑ Ueberschär (1998), pp. 960–966.

- ↑ Nenye et al. (2016), p. 64.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), pp. 290–291, 303–310.

- ↑ Mann & Jörgensen (2002), pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Ziemke (1959), p. 181.

Bibliography

- Inozemtzev, Ivan (1975). Крылатые защитники Севера [Winged defenders of the North] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Kiselev, Aleksey (1988). Мурманск — город-герой [Murmansk — hero city] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Mann, Chris M.; Jörgensen, Christer (2002). Hitler's Arctic War. Hersham, UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0-7110-2899-0.

- Nenye, Vesa; Munter, Peter; Wirtanen, Tony; Birks, Chris (2016). Finland at War: The Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1526-2.

- Shirokorad, Alexander (2001). Северные войны России [Northern wars of Russia] (in Russian). Moscow: AST. ISBN 0-7110-2899-0. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Ueberschär, Gerd R. (1998). "Strategy and Policy in Northern Europe". In Boog, Horst; Förster, Jürgen; Hoffmann, Joachim; Klink, Ernst; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R. (eds.). The Attack on the Soviet Union. Vol. IV. Translated by McMurry, Dean S.; Osers, Ewald; Willmot, Louise. Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Military History Research Office (Germany) ). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 941–1020. ISBN 0-19-822886-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Ziemke, Earl F. (1959). The German Northern Theater of Operations 1940–1945 (PDF). United States Government Printing. ISBN 0-16-001996-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

Further reading

- Jowett, Philip S.; Snodgrass, Brent (2006). Finland at War 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-969-X.