| Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Clay |

| Created | c. 1000 BC |

| Discovered | 2008 Beit Shemesh, Jerusalem, Israel |

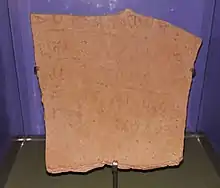

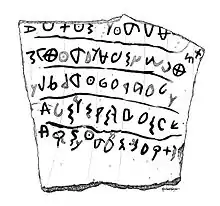

The Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon is a 15-by-16.5-centimetre (5.9 in × 6.5 in) ostracon (a trapezoid-shaped potsherd) with five lines of text,[1] discovered in Building II, Room B, in Area B of the excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa in 2008.[2] Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said the inscription was the longest Proto-Canaanite text ever found.[3] Carbon-14 dating of 4 olive pips found in the same context with the ostracon and pottery analysis offer a date of Iron Age IIA c. 3,000 years ago (late 11th/early 10th century BCE).[4]

In 2010, the ostracon was placed on display in the Iron Age gallery of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[5]

Epigraphic evaluations of the text

- Misgav, Garfinkel, and Ganor

The editio princeps of the inscription was published by Haggai Misgav, Yosef Garfinkel, and Saar Ganor in the 2009 Khirbet Qeiyafa excavation volume.[2] They proposed the following reading of the ostracon:

- 1 ʾ l t ʿ š [ ] w ʿ b d ʾ t

- 2 š p ṭ [?] b w ʾ l m [ ] b/ʾ l(?) ṭ

- 3 g/b/ʾ? [l?] b ʿ l? l g? ...

- 4 ʾ[ ] m w n q m? y ḥ/s d m l k p/g

- 5 ʾ/s? r/q m/ṣ/n ʿ b/ʾ d/š? ṣ? w/m/n d/g r t

While they did not offer a translation, they did suggest on the basis of a few extant lexemes that the inscription was the earliest example of Hebrew writing.[2]

- Yardeni

In the same volume, Ada Yadeni contributed an analysis of the ostracon. She proposed slightly different readings from Misgav, Garfinkel, and Ganor, though she also did not offer a translation:[6]

- 1 ʾltʿš ?] : wʿbdʾ[?] :

- 2 špṭ [?]b[?] wʾlm[?] špṭ y.

- 3 g[?]r[?]bʿll...m[?]ky

- 4 ʾ[?]m.nqmybdmlk

- 5 ḥrm[?].šk.grt.

- Galil

In a lengthy 2009 article, Gershon Galil of Haifa University proposed an expansive reading of the ostracon with translation:[7]

- 1 ʾl tʿs wʿbd ʾ[t] ...

- 2 špṭ [ʿ]b[d] wʿlm[n] špṭ yt[m]

- 3 [w]gr [r]b ʿll rb [d]l w

- 4 ʾ[l]mn šqm ybd mlk

- 5 ʿ[b]yn [w]ʿbd šk gr t[mk]

- 1 you shall not do [it], but worship (the god) [El]

- 2 Judge the sla[ve] and the wid[ow] / Judge the orph[an]

- 3 [and] the stranger. [Pl]ead for the infant / plead for the po[or and]

- 4 the widow. Rehabilitate [the poor] at the hands of the king

- 5 Protect the po[or and] the slave / [supp]ort the stranger.

Galil claimed that the language of the inscription is Hebrew and that 8 out of 18 words written on the inscription are exclusively biblical.[8]

On January 10, 2010, the University of Haifa issued a controversial press release claiming decipherment of the text and that it contained a social statement relating to slaves, widows and orphans. According to this interpretation, the text "uses verbs that were characteristic of Hebrew, such as ‘śh (עשה) ("did") and ‘bd (עבד) ("worked"), which were rarely used in other regional languages. Particular words that appear in the text, such as almanah ("widow") are specific to Hebrew and are written differently in other local languages. The content itself, it is argued, was also unfamiliar to all the cultures in the region other than that of Hebrew society. It was further maintained that the present inscription yielded social elements similar to those found in the biblical prophecies, markedly different from those current in other cultures, which write of the glorification of the gods and taking care of their physical needs."[1][5]

- Puech

In 2010, Émile Puech of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française proposed a reading of the ostracon with an accompanying translation:[9]

- 1 ʾl tʿšq wʿbd ʾ[l] ... [b]zh

- 2 špṭ wbk ʾlm[n] špṭ

- 3 bgr wbʿll qṣm yḥd

- 4 ʾ[d]m wšrm ysd mlk

- 5 ḥrm (ššm?) ʿbdm mdrt

- 1 Do not oppress, and serve God … despoiled him/her

- 2 The judge and the widow wept; he had the power

- 3 over the resident alien and the child, he eliminated them together

- 4 The men and the chiefs/officers have established a king

- 5 He marked 60 [?] servants among the communities/habitations/generations

Peuch considered the language to be Canaanite or Hebrew without Philistine influence.[10] He understood the ostracon to be a locally written copy of a message from the capital informing a local official of the ascent of Saul to the throne.[11]

- Millard

In the following year, Alan Millard contributed a restricted reading of the inscription, suggesting that it may be a list of names:[12]

- 1 ʾ l t ʿ š ? / w ʿ b d ʾ ? /

- 2 š p ṭ b ? ʾ l m ? š? p ṭ x x

- 3 ? g r x b ʿ l l x x x x x

- 4 ʾ x m w n q m y b d m l k x

- 5 ʾ/ḥ? r? m ʿ b? x š? k? g? r? t x

- 1 Ellat-ʿash and ʿEbed-ʾX

- 2 Shaphaṭ x x x x Shaphaṭ

- 3 x Ger? Baʿal-? x x x x x

- 4 ?? and Naqmay? Bodmilk

- 5 [Too Fragmentary]

Millard believes the inscription could have been written in any number of languages, including Hebrew, Canaanite, Phoenician, or Moabite. He believes that it most likely consists of a list of names written by someone unfamiliar with writing alphabetic.[12]

- Demsky

In 2012, Aaron Demsky of Bar-Ilan University contributed his reading of the ostracon: [13]

- 1 ʾ l t ʿ š [..] ʿ b d ʾ l(?)

- 2 špṭ b n? ʾ l m ? š? p? ṭ

- 3 gr ..... bʿl

- 4 ʾ [ ] m.w š? r? m.y b ʿ/d m l k

- 5 ḥ q s ʿ ..... g? r? t

Demsky argued that the inscription was a scribal exercise, perhaps written vertically, containing little more than indefinite nouns. He argued that no words in the inscription can be definitely identified as Hebrew.[13]

- Donnelly-Lewis

In a 2022 article in the Bulletin of ASOR, Brian Donnelly-Lewis proposed a near-complete reading of the text based on several unpublished multi-spectral images of the ostracon:[14]

- 1 ʾltʿštr ʿbd ʾḥ

- 2 špṭ | bd ʾlm tšpṭh z

- 3 spr db ʿl qṣr [ ]

- 4 ʾqm wyqmy bd mlk .

- 5 ʾqm [ ]y hdrt .

- 1 ʾElatʿaštar, servant of ʾḤ-

- 2 -ŠPṬ | By the gods may you judge him who

- 3 has recounted a false report about the harvest [<. In> the gate],

- 4 I will appear, since he summoned me by (the authority) of the king.

- 5 I will appear (in court) [and] you will rule in favor of my [case].

Donnelly-Lewis proposes that the language of the inscription is Hebrew on the basis of the morphology of the word "db" in line three.[14] He additionally interprets the inscription to be a record of a legal summons.[14]

Language and interpretation

As detailed above, several scholars suggest that the inscription contains a continuous text and that the language of the inscription can be identified as Hebrew (e.g. Misgav, Puech, Galil, and Donnelly-Lewis). Several others, however, argue that no distinct linguistic markers can be identified and that the inscription is probably just a list, either of names or of simple nouns (e.g. Millard, Demsky, and Rollston). Several studies of the later sort should be mentioned here. A 2011 article by Christopher Rollston presents his reflections on the inscription, including comments pertaining to its script and the possibility of identifying the language. [15] Rollston disputes the claim that the language is Hebrew, arguing that the words alleged to be indicative of Hebrew are either general Semitic terms, appearing in languages other than Hebrew, or simply do not appear in the inscription.[15] Using a computer-assisted approach, Levy and Pluquet give several readings for suggesting a list of personal names.[16] Finally, Matthieu Richelle in a 2015 article, proposed a few new readings in the first two lines, presenting an interpretation that these lines may contain exclusively personal names. [17]

Additional notes

The direction of writing and orientation of the letters have been two unresolved issues relating to the inscription. Many have taken the direction of writing to be left-to-right, though Rollston, Demsky, and Donnelly-Lewis all consider that the inscription could have been written vertically. The orientation of the letters, however, remains an issue of some curiosity. Brian Colless proposes that the different orientations of letters on the ostracon, such as three orientations of aleph, are intentional and represent differences in pronunciation.[18]

References

- 1 2 "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". University of Haifa. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Misgav, Haggai; Garfinkel, Yosef; Ganor, Saar (2009). "The Ostracon". In Garfinkel, Yosef; Ganor, Saar (eds.). Khirbet Qeiyafa, Vol. 1: Excavation Report 2007–2008. Jerusalem. pp. 243–257. ISBN 978-965-221-077-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "'Oldest Hebrew script' is found". BBC News. October 30, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Earliest known Hebrew text unearthed at 3,000 year old Judean fortress, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 30 Oct 2008. Accessed 18 February 2022.

- 1 2 "Qeiyafa Ostracon Chronicle". Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological Project. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ↑ Yardeni, Ada (2009). "Further Observation on the Ostracon". In Garfinkel, Yosef; Ganor, Saar (eds.). Khirbet Qeiyafa, Vol. 1: Excavation Report 2007–2008. Jerusalem. pp. 259–360. ISBN 978-965-221-077-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Gershon, Galil (2009). "The Hebrew Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa/Neṭaʿim: Script, Language, Literature, and History". Ugarit-Forschungen. 41: 193–242.

- ↑ "The keys to the kingdom". Haaretz.com. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ Émile Puech (2010). "l'ostracon de Khirbet Qeyafa et les débuts de la royauté en Israël". Revue Biblique. 117 (2): 162–184.

- ↑ Émile Puech (2010). "l'ostracon de Khirbet Qeyafa et les débuts de la royauté en Israël". Revue Biblique. 117 (2): 162–184.

On a affaire au premier document de quelque longueur, en langue cananéenne ou hébraïque, bien daté et de quelque importance pour l'histoire de la langue, de l'orthographe et pour l'histoire en général, sans une quelconque influence philistine.

- ↑ Leval, Gerard (2012). "Ancient Inscription Refers to Birth of Israelite Monarchy." Biblical Archaeology Review. May/June 2012, 41-43, 70.

- 1 2 Alan Millard (2011). "The ostracon from the days of David found at Khirbet Qeiyafa". Tyndale Bulletin. 62 (1): 1–14.

- 1 2 Demsky, Aaron (2012). "An Iron Age IIA Alphabetic Writing Exercise from Khirbet Qeiyafa". Israel Exploration Journal. 62: 186–199.

- 1 2 3 Donnelly-Lewis, Brian (2022). "The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon: A New Collation Based on Multispectral Images, with Translation and Commentary". Bulletin of ASOR. 388: 181–210.

- 1 2 Rollston, Christopher (June 2011). "The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon: Methodological Musings and Caveats". Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. 38 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1179/033443511x12931017059387. S2CID 153359230.

- ↑ Eythan Levy and Frédérik Pluquet (2007). "Computer experiments on the Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon". Digital Scholarship in the Humanities: fqw028. doi:10.1093/llc/fqw028.

- ↑ Richelle, Matthieu (2015). "Quelques nouvelles lectures sur l'ostracon de Khirbet Qeiyafa". Semitica. 57: 147–162.

- ↑ "The Lost Link - The Alphabet in the Hands of the Early Israelites". ASOR. 1 Feb 2014. Retrieved 28 Aug 2022.