Kingdom of Kosala कोसल राज्य | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 7th century BCE[1]–c. 5th century BCE | |||||||||

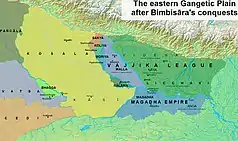

Kosala and its neighboring kingdoms. | |||||||||

.png.webp) Kosala and other Mahajanapada in the Post Vedic period. | |||||||||

| Capital | Ayodhya and Shravasti of Uttar Kosala | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Historical Vedic religion Jainism Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• ? | Ikshvaku (first) | ||||||||

• c. 5th century BCE | Sumitra (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 7th century BCE[1] | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 5th century BCE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India Nepal | ||||||||

Kosala (Sanskrit: कोसल), sometimes referred as "Uttara Kosala" transl. "Northern Kosala"[2]) was one of the sixteen great realms of ancient India.[3][4] It emerged as a small state during the Late Vedic period[5][6] and became (along with Magadha) one of the earliest states to transition from a lineage-based society to a monarchy.[7] By the 6th century BCE, it had consolidated into one of the four great powers of ancient northern India, along with Magadha, Vatsa, and Avanti.[3][8]

Kosala belonged to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture (c. 700–300 BCE)[1] and was culturally distinct from the Painted Grey Ware culture of the neighboring Kuru-Panchala region, following independent development toward urbanisation and the use of iron.[9] The presence of the lineage of Ikshavaku—described as a raja in the Ṛgveda and an ancient hero in the Atharvaveda[10]—to which Rama, Mahavira, and the Buddha are all thought to have belonged—characterized the Kosalan realm.[11][12]

One of India's two great epics, Ramayana is set in the "Kosala-Videha" realm in which the Kosalan prince Rama marries the Videhan princess Sita.

After a series of wars with neighbouring kingdoms, it was finally defeated and absorbed into the Magadha kingdom in the 5th century BCE. After the collapse of the Maurya Empire and before the expansion of the Kushan Empire, Kosala was ruled by the Deva dynasty, the Datta dynasty, and the Mitra dynasty.

Location

Geography

Kosala was bounded by the Gomti River in the west, Sarpika River in the south, Sadanira in the east which separated it from Videha, and the Nepal Hills in the north. It encompassed the territories of the Shakyans, Mallakas, Koliyas, Kālāmas and Moriyas at its peak. It roughly corresponds to modern-day Awadh region in India.[13]

Cities and towns

The Kosala region had three major cities, Ayodhya, Saketa and Shravasti, and a number of minor towns as Setavya, Ukattha,[14] Dandakappa, Nalakapana and Pankadha.[15] According to the Puranas and the Ramayana epic, Ayodhya was the capital of Kosala during the reign of Ikshvaku and his descendants.[16] Shravasti is recorded as the capital of Kosala during the Mahajanapada period (6th–5th centuries BCE),[17] but post-Maurya (2nd–1st centuries BCE) kings issued their coins from Ayodhya.

Culture

Kosala belonged to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture (c. 700–300 BCE),[1] which was preceded by the Black and red ware culture (c. 1450–1200 BCE until c. 700–500 BCE). The Central Gangetic Plain was the earliest area for rice cultivation in South Asia, and entered the Iron Age around 700 BCE.[1] According to Geoffrey Samuel, following Tim Hopkins, the Central Gangetic Plain was culturally distinct from the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Vedic Aryans of Kuru-Pancala west of it, and saw an independent development toward urbanisation and the use of iron.[9]

Religion

Kosala was situated at the crossroads of Vedic heartland of Kuru-Panchala and Greater Magadhan culture.[18] According to Alexander Wynne, Kosala-Videha culture was at the center of unorthodox Vedic traditions, ascetic and speculative traditions, possibly reaching back to the late Ṛgveda.[19] Kosala-Videha culture is thought to be the home of the Śukla school of the Yajurveda.[20]

According to Michael Witzel and Joel Brenton, the Kāṇva school of Vedic traditions (and in turn the first Upanishad i.e, Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad) was based in Kosala during the middle and late Vedic periods.[21] Kosala had a significant presence of the muni tradition,[22] which included Buddhists, Jains, Ajivikas, Naga, Yakṣa, and tree worshipers as well as Vedic munis.[23][24] The muni tradition emphasized on "practicing yoga, meditation, renunciation and wandering mendicancy" as contrasted to the ṛṣis who "recited prayers, conducted homa, and led a householder lifestyle".[23]

According to Samuel, there is "extensive iconographical evidence for a religion of fertility and auspiciousness".[25] According to Hopkins, the region was marked by a

...world of female powers, natural transformation, sacred earth and sacred places, blood sacrifices, and ritualists who accepted pollution on behalf of their community.[25]

Buddhism

Kosala had a particularly strong connection to the Buddha's life. Buddha introduced himself to the king of Magadha in the Suttanipata as a Kosalan.[26] In the Majjhima Nikāya too, king Prasenajit refers to Buddha as a Kosalan.[27] He spent much of his time teaching in Śrāvastī, especially in the Jetavana monastery.[28] According to Samuels, early Buddhism was not a protest against an already established Vedic-Brahmanical system, which developed in Kuru-Pancala realm, but an opposition against the growing influence of this Vedic-Brahmanical system, and the superior position granted to Brahmins in it.[29]

Religious textual references

In Buddhist and Jain texts

Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism taught in Kosala. A Buddhist text, the Majjhima Nikaya mentions Buddha as a Kosalan, which indicates that Kosala may have subjugated the Shakya clan, which the Buddha is traditionally believed to have belonged to.[31]

In Vedic Literature

Kosala is not mentioned in the early Vedic literature, but appears as a region in the later Vedic texts of the Shatapatha Brahmana (7th-6th centuries BCE,[32] final version 300 BCE[33]) and the Kalpasutras (6th-century BCE).[34]

In Puranas

In the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas the ruling family of the Kosala kingdom was the Ikshvaku dynasty, which was descended from king Ikshvaku.[35] The Puranas give lists of kings of the Ikshvaku dynasty from Ikshvaku to Prasenajit (Pali: Pasenadi).[36] According to the Ramayana, Rama ruled the Kosala kingdom from his capital, Ayodhya.[37]

History

Pre-Mauryan

Koshala's first capital of Shravasti was barely settled by the 6th century BCE, but there is the beginnings of a mud fort. By 500 BCE, Vedic people had spread to Koshala. [38]

By the 5th century BCE under the reign of King Mahakosala, the neighboring Kingdom of Kashi had been conquered.[39] Mahakosala's daughter was the first wife of King Bimbisara of Magadha. As a dowry, Bimbisara received a Kashi village that had a revenue of 100,000. This marriage temporarily eased tensions between Koshala and Magadha.[38]

By the time of Mahākosala's son Pasenadi, Kosala had become the suzerain of the Kālāma tribal republic,[40] and Pasenadi's realm maintained friendly relations with the powerful Licchavi tribe which lived to the east of his kingdom.[41]

During Pasenadi's reign, a Mallaka named Bandhula who had received education in Takṣaśilā, had offered his services as a general to the Kauśalya king so as to maintain the good relations between the Mallakas and Kosala. Later, Bandhula, along with his wife Mallikā, violated the Abhiseka-Pokkharaṇī sacred tank of the Licchavikas, which resulted in armed hostilities between the Kauśalya and the Licchavikas. Bandhula was later treacherously murdered along with his sons by Pasenadi. In retaliation, some Mallakas helped Pasenadi's son Viḍūḍabha usurp the throne of Kosala to avenge the death of Bandhula, after which Pasenadi fled from Kosala and died in front of the gates of the Māgadhī capital of Rājagaha.[42]

At some point during his reign, Viḍūḍabha fully annexed the Kālāmas. That the Kālāmas did not request a share of the Buddha's relics after his death was possibly because they had lost their independence by then.[40]

Shortly after the Buddha's death, the Viḍūḍabha invaded the Sakya and Koliya republics, seeking to conquer their territories because they had once been part of Kosala. Viḍūḍabha finally triumphed over the Sakyas and Koliyas and annexed their state after a long war with massive loss of lives on both sides. Details of this war were exaggerated by later Buddhist accounts, which claimed that Viḍūḍabha's invasion was in retaliation for having given in marriage to his father the slave girl who became Viḍūḍabha's mother, and that he exterminated the Sakyas. In actuality, Viḍūḍabha's invasion of Sakya might instead have had similar motivations to the Māgadhī king Ajātasattu's conquest of the Vajjika League because he was the son of a Vajjika princess and was therefore interested in the territory of his mother's homeland. The result of the Kauśalya invasion was that the Sakyas and Koliyas were absorbed into Viḍūḍabha's kingdom.[43][44]

The massive life losses incurred by Kosala during its conquest of Sakya weakened it significantly enough that it was itself was soon annexed by its eastern neighbour, the kingdom of Magadha, and Viḍūḍabha was defeated and killed by the Māgadhī king Ajātasattu.[43]

Under the reign of Mahapadma Nanda of Magadha, Koshala rebelled but the rebellion was put down.[38]

Under Mauryan rule

It is assumed that during the Mauryan reign, Kosala was administratively under the viceroy at Kaushambi.[45] The Sohgaura copper plate inscription, probably issued during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya deals with a famine in Shravasti and the relief measures to be adopted by the officials.[46] The Yuga Purana section of the Garga Samhita mentions about the Yavana (Indo-Greek) invasion and subsequent occupation of Saket during the reign of the last Maurya ruler Brihadratha.[47]

Post-Mauryan period

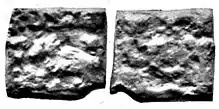

Kashi coin, 400-300 BCE.

Kashi coin, 400-300 BCE.

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

The names of a number of rulers of Kosala of the post-Maurya period are known from the square copper coins issued by them, mostly found at Ayodhya.[48] The rulers, forming the Deva dynasty, are: Muladeva, Vayudeva, Vishakhadeva, Dhanadeva, Naradatta, Jyesthadatta and Shivadatta. There is no way to know whether king Muladeva of the coins is identifiable with Muladeva, murderer of the Shunga ruler Vasumitra or not (though a historian, Jagannath has tried to do so).[49] King Dhanadeva of the coins is identified with king Dhanadeva (1st century BCE) of Ayodhya inscription. In this Sanskrit inscription, King Kaushikiputra Dhanadeva mentions about setting a ketana (flag-staff) in memory of his father, Phalgudeva. In this inscription he claimed himself as the sixth in descent from Pushyamitra Shunga. Dhanadeva issued both cast and die-struck coins and both the types have a bull on obverse.[50][51]

Other local rulers whose coins were found in Kosala include: a group of rulers whose name ends in "-mitra" is also known from their coins: Satyamitra, Aryamitra, Vijayamitra and Devamitra, sometimes called the "Late Mitra dynasty of Kosala".[52] Other rulers known from their coins are: Kumudasena, Ajavarman and Sanghamitra.[53]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Samuel 2010, p. 50.

- ↑ Hira Lal 1986, p. 161 footnote.

- 1 2 "Kosala | ancient kingdom, India | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

Kosala rose in political importance early in the 6th century BCE to become one of the 16 states dominant in northern India. It annexed the powerful kingdom of Kashi. About 500 BCE, during the reign of King Prasenajit (Pasenadi), it was regarded as one of the four powers of the north—perhaps the dominant power.

- ↑ Mahajan 1960, p. 230.

- ↑ Samuel 2010, p. 61–63.

- ↑ Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, 97–265.

- ↑ Thapar (2013:260) - Interestingly, in the transition from lineage-based societies to states, it is Magadha and Kosala which emerge among the earlier states that move towards kingdoms.

- ↑ Vikas Nain, "Second Urbanization in the Chronology of Indian History", International Journal of Academic Research and Development 3 (2) (March 2018), pp. 538–542 "Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced into four major ones by 500/400 BCE, by the time of Gautama Buddha. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha."

- 1 2 Samuel 2010, p. 50-51.

- ↑ Thapar (2013:138) - There is a single reference in the Ṛgveda to Ikṣvāku as a rājā, and the Atharvaveda refers to him as an ancient hero.

- ↑ Thapar (2013:287) - Manu’s eldest son, Ikṣvāku, the progenitor of the Sūryavaṃśa, had three sons, two of whom were important and established themselves at Kosala and Videha, contiguous territories in the middle Ganges plain and important to the narrative of the Rāmāyaṇa. The rulers of Kosala and Videha are therefore of collateral lines.

- ↑ Peter Scharf. Ramopakhyana – The Story of Rama in the Mahabharata: A Sanskrit Independent-Study Reader. Routledge, 2014. p. 559.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, pp. 77–79, 99

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, p. 89.

- ↑ Law 1973, p. 132.

- ↑ Pargiter 1972, p. 257.

- ↑ Samuel 2010, p. 71.

- ↑ Bausch (2015:28) - Kosala thrived on the edge of both the Vedic world and Greater Magadha, where it formed an important center during the lifetimes of the Vedic sage Yājñavalkya as well as Sakyamuni Buddha.

- ↑ Wynne, A. (2011). "Review of Johannes Bronkhorst. Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India." Buddhism commissioned by David Arnold.

- ↑ Johnson, W. J. (2009), "Kosala-Videha", A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0, retrieved 11 June 2023

- ↑ Bausch (2015:19)

- ↑ Bausch (2015:1-2,28) After Janaka, when the Vajjis surpassed the Videhas, Kosala emerged as a major center of political power and muni religious activity.

- 1 2 Bausch (2018:30)

- ↑ Samuel 2010, p. 48.

- 1 2 Samuel 2010, p. 61.

- ↑ Bausch (2018:28-29) - According to the Suttanipāta, Gotama Buddha’s hometown was located in the region of Kosala, what is today eastern Uttar Pradesh. In the Pabbajjāsutta (Sn 3.1), Gotama Buddha explains his personal background to Magadhan King Bimbisāra, telling him that he hails from a country in Kosala.

- ↑ Bausch (2018:29) - In an account given in the Majjhimanikāya, King Pasenadi of Kosala calls the Buddha a Kosalan.

- ↑ Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2017), "Kośala", The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780190681159.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3, retrieved 11 June 2023

- ↑ Samuel 2010, p. 100.

- ↑ Marshall p.59

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, pp. 88–9

- ↑ "Early Indian history: Linguistic and textual parametres." in The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, edited by G. Erdosy (1995), p. 136

- ↑ The Satapatha Brahmana. Sacred Books of the East, Vols. 12, 26, 24, 37, 47, translated by Julius Eggeling [published between 1882 and 1900]

- ↑ Law 1926, pp. 34–85

- ↑ Sastri 1988, p. 17.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, pp. 89–90

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, pp. 68–70

- 1 2 3 Sharma, R. S. (2005). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-0-19-908786-0.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri 1972, p. 138

- 1 2 Sharma 1968, p. 231-236.

- ↑ Sharma 1968, p. 121.

- ↑ Sharma 1968, p. 178-180.

- 1 2 Sharma 1968, p. 182-206.

- ↑ Sharma 1968, p. 207-217.

- ↑ Mahajan 1960, p. 318

- ↑ Thapar 2001, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Lahiri 1974, pp. 21–4

- ↑ Bhandare (2006)

- ↑ Lahiri 1974, p. 141n

- ↑ Bhandare 2006, pp. 77–8, 87–8

- ↑ Falk 2006, p. 149

- ↑ Proceedings - Indian History Congress - Volume 1 - Page 74

- ↑ Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (3 November 1968). "Papers on the Date of Kaniṣka: Submitted to the Conference on the Date of Kaniṣka, London, 20-22 April 1960". Brill Archive – via Google Books.

Sources

- Thapar, Romila (2013). The Past Before Us: Historical Traditions of Early North India (1 ed.). Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72523-2.

- Hira Lal (1986) [1933]. "The Extent and Capital of Daksina Kosala". Indian Antiquary. Swati. 62.

- Bhandare, S. (2006), Numismatic Overview of the Maurya-Gupta Interlude in P. Olivelle (ed.), Between the Empires: Society in India 200 BCE to 400 CE, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-568935-6.

- Falk, H. (2006), The Tidal Waves of Indian History in P. Olivelle (ed.), Between the Empires: Society in India 200 BCE to 400 CE, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-568935-6

- Lahiri, B. (1974), Indigenous States of Northern India (Circa 300 B.C. to 200 A.D.), Calcutta: University of Calcutta

- Law, B. C. (1973), Tribes in Ancient India, Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

- Law, B.C. (1926), Ancient Indian Tribes, Lahore: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 9781406751802

- Mahajan, V.D. (1960), Ancient India, New Delhi: S. Chand, ISBN 81-219-0887-6

- Pargiter, F.E. (1972), Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Raychaudhuri, H.C. (1972), Political History of Ancient India, Calcutta: University of Calcutta

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, pp. 61–63.

- Thapar, R. (2001), Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta, ed. (1988) [1967], Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0465-1

- Sharma, J. P. (1968). Republics in Ancient India, C. 1500 B.C.-500 B.C. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-02015-3.

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9

- Kosambi, D.D. (1952), Ancient Kosala and Magadha, Bombay Branch Royal Asiatic Society

- Bausch, L. M. (2015), Kosalan Philosophy in the" Kānva Śatapatha Brāhmana" and the "Suttanipāta", University of California, Berkeley

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007), Greater Magadha, BRILL, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004157194.i-416, ISBN 978-90-474-1965-5

- Bausch, Lauren M. (2018). "The Kāṇva Brāhmanas and Buddhists in Kosala". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 41. doi:10.2143/JIABS.41.0.3285738.