| King of Akkad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Sargon |

| Last monarch | Shu-turul |

| Formation | c. 2334 BC |

| Abolition | c. 2154 BC 530 BC (King of Sumer and Akkad) |

| Appointer | Divine right, hereditary |

The king of Akkad (Akkadian: šar māt Akkadi, lit. 'king of the land of Akkad'[1]) was the ruler of the city of Akkad and its empire, in ancient Mesopotamia. In the 3rd millennium BC, from the reign of Sargon of Akkad to the reign of his great-grandson Shar-Kali-Sharri, the Akkadian Empire represented the dominant power in Mesopotamia and the first known great empire.

The empire would rapidly collapse following the rule of its first five kings, owing to internal instability and foreign invasion, probably resulting in Mesopotamia re-fracturing into independent city-states, but the power that Akkad had briefly exerted ensured that its prestige and legacy would be claimed by monarchs for centuries to come. Ur-Nammu of Ur, who founded the Neo-Sumerian Empire and reunified most of Mesopotamia, created the title "King of Sumer and Akkad" which would be used until the days of the Achaemenid Empire.

History

Although Sargon of Akkad is often referred to as the "founder" of Akkad, the city itself probably existed before his rule; a pre-Sargonic inscription refers to it by name and the name "Akkad" itself is not actually of the Akkadian language of Sargon and his successors.[2][3] Sargon's reign does however mark the transition of Akkad from a city-state into the first known great empire, with the Akkadian king ruling all Mesopotamia. His rise to power began with the defeat of the Sumerian king Lugal-zage-si, who had ruled Lower Mesopotamia from Uruk, and the conquest of his empire.[4] Through military campaigns, Sargon subjugated regions as far west as the Mediterranean and as far north as Assyria, which he boasted of in his inscriptions.[5]

Sargon's successors consolidated his vast realm and continued expanding the borders of the Akkadian Empire. Sargon's grandson and the fourth king of Akkad, Naram-Sin, brought the empire to its greatest extent and assumed a new title to illustrate his great power, King of the Four Quarters, which referenced the entire world. He was also the first king in Mesopotamia to be deified in his lifetime, being addressed as "the god of Akkad".[6][7]

Although at least seven kings would rule Akkad after him, the Akkadian Empire quickly collapsed after Naram-Sin's reign and prominent central authority under a single king would not be restored in Mesopotamia until the rise of the Neo-Sumerian Empire. It's likely that the region reverted to local governance under kings of city-states in the time between the two empires.[8] A major cause of this collapse was the invasion of Mesopotamia by a people referred to as the Gutians, who would be defeated and driven away by the founder of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, Ur-Nammu.

Kings of Akkad

Sargonic dynasty (c. 2334 – 2193 BC)

| # | Depiction | King | Reign (Middle Chronology) | Succession | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Sargon 𒈗𒁺 Šarru-ukīn |

c. 2334–2279 BC (55 years) |

Founder of the Akkadian Empire |

|

| 2 |  |

Rimush 𒌷𒈬𒍑 Ri-mu-uš |

c. 2279–2270 BC (9 years) |

Son of Sargon of Akkad | |

| 3 |  |

Manishtushu 𒈠𒀭𒅖𒌅𒋢 Ma-an-ish-tu-su |

c. 2270–2255 BC (15 years) |

Brother of Rimush, son of Sargon of Akkad |

|

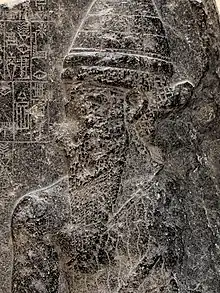

| 4 | .jpg.webp) |

Naram-Sin 𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 Na-ra-am Sîn |

c. 2254–2218 BC (36 years) |

Son of Manishtushu |

|

| 5 |  |

Shar-Kali-Sharri 𒊬𒂵𒉌 𒈗𒌷 Šar-ka-li-šar-ri |

c. 2217–2193 BC (24 years) |

Son of Naram-Sin |

|

Akkadian interregnum (c. 2193 – 2189 BC)

| # | King | Reign (Middle Chronology) | Succession | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Igigi 𒄿𒄀𒄀 I-gi-gi |

c. 2193–2192 BC (1 year) |

Uncertain succession, anarchy following the Guti invasion |

|

| 7 | Imi 𒄿𒈪 I-mi |

c. 2192–2191 BC (1 year) |

Uncertain succession, anarchy following the Guti invasion | |

| 8 | Nanum 𒈾𒉡𒌝 Na-nu-um |

c. 2191–2190 BC (1 year) |

Uncertain succession, anarchy following the Guti invasion | |

| 9 | Ilulu 𒅋𒇽 Ilu-lu |

c. 2190–2189 BC (1 year) |

Uncertain succession, anarchy following the Guti invasion |

|

Final kings of Akkad (c. 2189 – 2154 BC)

The final kings to rule Akkad, Dudu and Shu-turul are assumed to have been related to the original ruling dynasty and as such are often regarded as members of the Sargonic dynasty.[9]

| # | King | Reign (Middle Chronology) | Succession | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Dudu 𒁺𒁺 Du-du |

c. 2189–2168 BC (21 years) |

Uncertain succession, anarchy following the Guti invasion, possibly the son of Shar-Kali-Sharri | |

| 11 | Shu-turul 𒋗𒉣𒇬𒍌 Šu-ṭur-ul |

c. 2168–2154 BC (15 years) |

Son of Dudu |

King of Sumer and Akkad

Although Akkad and what remained of its empire was destroyed, its power and prominence led to rulers of later Mesopotamian empires wishing to claim its prestige and legacy for themselves. Ur-Nammu, who founded the Neo-Sumerian Empire in the aftermath of the Gutian rule of Mesopotamia assumed the title "King of Sumer and Akkad". Although the title was meant to justify his rule over both southern (Sumer) and northern (Akkad) Mesopotamia, it also clearly connected Ur-Nammu to the old Akkadian kings,[10] who may have been against linking Sumer and Akkad in such a fashion even though they had ruled both regions.[11]

Ur-Nammu's title would endure for more than 1,500 years. It was assumed by Hammurabi, founder of the Old Babylonian Empire, and used by Babylonian kings up until the 8th century BC.[12] It was also prominently used in the Middle and Neo-Assyrian Empires[12] and in the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[1] For Assyrian kings, "King of Sumer and Akkad" was used as a marker of their control of Babylon (which was in the South, e.g. Sumer) and only those Assyrian kings who actually controlled Babylon used the title in their inscriptions.[12]

The final king to assume the title of "King of Sumer and Akkad" was Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire, who reigned from 559 to 530 BC. In the Cyrus Cylinder, written in Akkadian cuneiform script following Cyrus's conquest of Babylon, he assumed several traditional Mesopotamian royal titles, most of which were not used by his successors.[13]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Da Riva 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Wall-Romana, Christophe (1990). "An Areal Location of Agade". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 205–245. doi:10.1086/373442. JSTOR 546244. S2CID 161165836.

- ↑ Foster, Benjamin R. (2013), "Akkad (Agade)", in Bagnall, Roger S. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Chicago: Blackwell, pp. 266–267, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah01005, ISBN 9781444338386

- ↑ Stiebing Jr, H. William (2009). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Pearson Longman; University of New Orleans. p. 69.

- ↑ Dalley proposes that these sources may have originally referred to Sargon II of the Assyria rather than Sargon of Akkad. Stephanie Dalley, "Babylon as a Name for Other Cities Including Nineveh", in Proceedings of the 51st Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Oriental Institute SAOC 62, pp. 25–33, 2005

- ↑ Stiebing Jr, H.William. Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. (Pearson Longman; University of New Orleans, 2009), p.74

- ↑ Piotr Michalowski, "The Mortal Kings of Ur: A Short Century of Divine Rule in Ancient Mesopotamia", Oriental Institute Seminars 4, pp. 33–45, The Oriental Institute, 2008, ISBN 1-885923-55-4

- ↑ Zettler (2003), pp. 24–25. "Moreover, the Dynasty of Akkade's fall did not lead to social collapse, but the re-emergence of the normative political organization. The southern cities reasserted their independence, and if we know little about the period between the death of Sharkalisharri and the accession of Urnamma, it may be due more to accidents of discovery than because of widespread 'collapse.' The extensive French excavations at Tello produced relevant remains dating right through the period."

- ↑ De Mieroop 2004, p. 67.

- ↑ Maeda 1981, p. 5.

- ↑ Hallo 1980, p. 192.

- 1 2 3 Porter 1994, p. 79.

- ↑ New Cyrus Cylinder Translation.

Cited bibliography

- Da Riva, Rocío (2013). The Inscriptions of Nabopolassar, Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1614515876.

- De Mieroop, Marc Van (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405149112.

- Hallo, William W. (1980). "Royal Titles from the Mesopotamian Periphery". Anatolian Studies. 30: 189–195. doi:10.2307/3642789. JSTOR 3642789. S2CID 163327812.

- Maeda, Tohru (1981). ""King of Kish" in Pre-Sargonic Sumer". Orient. 17: 1–17. doi:10.5356/orient1960.17.1.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1994). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871692085.

- Zettler, Richard L. (2003). "Reconstructing the World of Ancient Mesopotamia: Divided Beginnings and Holistic History". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 46 (1): 3–45. doi:10.1163/156852003763504320. JSTOR 3632803.

Websites

- "British Museum - The Cyrus Cylinder". www.britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Farrokh, Kaveh. "A New Translation of the Cyrus Cylinder by the British Museum". kavehfarrokh.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.