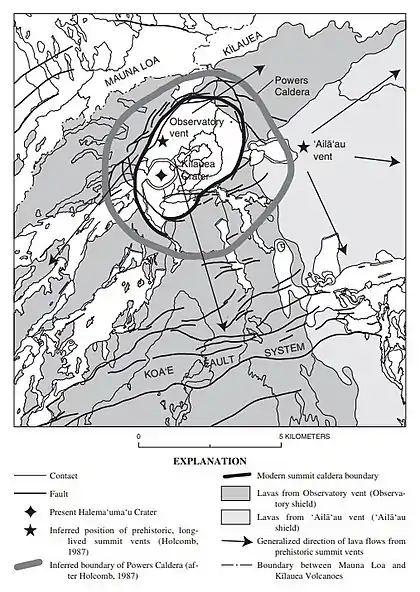

The Koa’e Fault Zone or Koa’e Fault System (pronounced coe-wah-hee) is a series of fault scarps connecting the East and Southwest Rift Zones on Kilauea Volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii. The fault zone intersects the East Rift near the Pauahi Crater and extends nearly 12 km (7.5 mi) in an east-northeast direction towards the westernmost boundary near Mauna Iki and the Southwest Rift Zone. Boundaries of the Koa’e Fault Zone also cover 2 km (1.2 mi) in a north-south orientation along the 12 km (7.5 mi) length. It is believed that the fault zone has been active for tens of thousands of years. The area is infrequently visited by park patrons due to the lack of eruptive activity and closure of certain areas to the general public.

Features

The Koa’e Fault Zone contains numerous thrust fault scarps and ground cracks that are slowly moving towards the Pacific Ocean. The area is covered with pahoehoe lava flows dated between 700 and 500 years old. The exact number of lava flows in this region is debatable. Numerous exposed scarps have very poor distinctions between various lava flows due to weathering of the basalt. Because Kilauea has erupted explosively in the past, the Koa’e Fault Zone is also covered with tephra deposits. The stratigraphy of the sediments contains many clues to the eruptive history of Kilauea Volcano.

- A layer of scoria overlies the basaltic lava flows. The age of these deposits has been determined to be roughly 400 years old. Groundwater penetration into Kilauea most likely created a steam explosion followed by an eruption of these tephra deposits.

- Above the scoria is a layer of orange ash roughly 3 cm (1.2 in) thick. The fined grained texture of the ash also suggests an explosive style of eruption sometime after the tephra was deposited. Biologists believe that this layer of ash served as a soil horizon for native and invasive plants to colonize the area.

- The top layer is a sandy material which is also the product of an explosive eruption.

In order to get a stratigraphy like this, a large eruption with tephra reaching the jet stream is required, suggesting that energetic pyroclastic eruptions have occurred in the past, making Kilauea significantly more hazardous than once thought.

Fault scarps in the Koa’e Fault Zone create a Horst and Graben type of terrain. Some of the scarps (called “pali” in native Hawaiian) face northwards, towards the summit of Kilauea Volcano and Halemaʻumaʻu Crater. This is unusual because the scarps usually face in the direction of flow. Monitoring data of the fault zone has revealed that at the Pacific Ocean, the land mass is moving at a rate of 2.5 cm (0.98 in) per year. In the upper regions of the fault zone, the crust is moving at a rate of 8 cm (3.1 in) annually. This vast difference in movement rates has over time created numerous antiforms in the region.

Kulanaokuaiki Pali is the southernmost fault in the Koa’e Fault Zone. During a period of intense earthquakes in December 1965, Kulanaokuaiki Pali was vertically displaced by more than 2.4 m (7.9 ft) meters. The region has been intensively studied since then. Displacements in other parts of the Koa’e Fault Zone based on historical data suggest that movements as great as 15 m (49 ft) have occurred.

Mechanics

The Koa’e Fault Zone is one of the most active fault zones in the entire world. Some scientists have interpreted the Koa’e Fault System as a break away structure as a direct result from the southward displacement of the southern flank of Kilauea. Movement along the Koa’e Fault Zone is being caused by slow slip displacement along basal detachment faults between 5-9 km at depth at about 25 cm per year. This slipping motion is caused by gravitational forces acting on the massive weight of the volcano as well as magmatic activity, which increases temperature and pore pressure, and decreases friction along the fault plane. Movement along the fault plane results in accumulating stress that can often be released by the forceful injection of magmatic dikes into the East and Southwest Rift Zones resulting in earthquakes.[1]

Along the Koa’e Fault Zone, there was a Mw 7.7 earthquake in 1975, and a Mw 7.2 earthquake in 2018. Though it is impossible to predict when large scale earthquakes will occur, researchers suggest that it could take another 25-30 years for enough stress to accumulate along the fault zone to cause another Mw >7 earthquake to occur.

Bathymetric contouring of the seafloor off the south coast of the Big Island, have revealed that massive landslides have occurred in Kilauea's past, most likely as the result of rifting and catastrophic collapse.

References

- ↑ Chen, Kejie; Smith, Jonathan D.; Avouac, Jean‐Philippe; Liu, Zhen; Song, Y. Tony; Gualandi, Adriano (2019-03-16). "Triggering of the Mw 7.2 Hawaii Earthquake of 4 May 2018 by a Dike Intrusion". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (5): 2503–2510. doi:10.1029/2018GL081428. ISSN 0094-8276.

Chen, K., Smith, J. D., Avouac, J.P.,Liu, Z., Song, Y. T., & Gualandi, A., (2019). Triggering of the Mw 7.2 Hawaii earthquake of 4 May 2018 by a dike intrusion. Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 2503–2510. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL081428

- Geological Field Guide: Kilauea Volcano. Revised edition. Claremont, CA: Hawai'i Natural History Association, 2002. 131–135. Print.

- "Measuring Ground Movements in the Koa`e Fault System." USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO). 7th Apr. 2003. Web. 06 Oct. 2010. <http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/2003/03_04_03.html>.

- Bush, Tom A., and Donald Swanson. "Field Guide to the Hawai'i Island Field Guide." Koa'e Fault Zone Hike. Koa'e Fault Zone. 10th Sept. 2009. Lecture.

- Swanson, Donald A., Richard S. Fiske, Timothy R. Rose, Duane E. Champion, and John P. McGeehin. "Sign In — Geological Society of America Bulletin." Geological Society of America Bulletin. May 2009. Web. 06 Oct. 2010. <http://gsabulletin.gsapubs.org/content/121/5-6/712.full>.