Mehmed | |

|---|---|

| |

| Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office 15 September 1656 – 31 October 1661 | |

| Monarch | Mehmed IV |

| Preceded by | Boynuyaralı Mehmed Pasha |

| Succeeded by | Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed Pasha |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1575 Roshnik, Sanjak of Avlona (now Albania) |

| Died | 31 October 1661 (aged 85-86) Edirne, Ottoman Empire |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Spouse | Ayşe Hatun |

| Relations | Köprülüzade Numan Pasha (grandson) Amcazade Köprülü Hüseyin Pasha (nephew) Kara Mustafa Pasha (son-in-law) Abaza Siyavuş Pasha (son-in-law) |

| Children | Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha Köprülüzade Fazıl Mustafa Pasha |

| Family | Köprülü family |

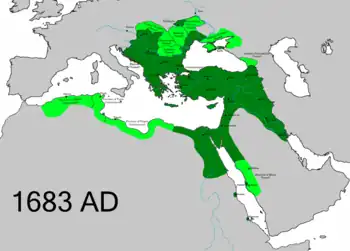

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha (Ottoman Turkish: كپرولی محمد پاشا, Turkish: Köprülü Mehmet Paşa, pronounced [ˈcœp.ɾy.ly mehˈmet paˈʃa]; Albanian: Mehmed Pashë Kypriljoti or Qyprilliu, also called Mehmed Pashá Rojniku; c. 1575, Roshnik,– 31 October 1661, Edirne) was Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire and founding patriarch of the Köprülü political dynasty, a family of viziers, warriors, and statesmen who dominated the administration of the Ottoman Empire during the last half of the 17th century, an era known as the Köprülü era.[1] He helped rebuild the power of the empire by rooting out corruption and reorganizing the Ottoman army. As he introduced these changes, Köprülü also expanded the borders of the empire, defeating the Cossacks, the Hungarians, and most impressively, the Venetians. Köprülü's effectiveness was matched by his reputation.[2]

Biography

Early life

He was born in the village of Rudnik in the Sanjak of Berat, Albania to Albanian parents.[3] He entered the sultan's service as a devşirme youth and was trained in the palace school.[4] Köprülü began as a kitchen boy in the imperial kitchen before transferring to the imperial treasury and then the offices of the palace chamberlain. Other officials reportedly found it difficult to work with Köprülü, and he was transferred to the sipahi (cavalry) corps in the provinces.[2]

Rise through the imperial service

He was first stationed in the town of Köprü in northern Turkey, which was later named Vezirköprü in his honour. He quickly rose in rank, keeping the name Köprülü, meaning from Köprü. Köprülü's former mentor, Hüsrev Pasha, rose in the imperial service and promoted Köprülü to increasingly important offices.[4] When Hüsrev was assassinated, however, Köprülü built up his own following. He eventually held important offices as head of the market police in Constantinople, supervisor of the Imperial Arsenal, chief of the Sipahi corps (mirahor), and head of the corps armorers. Köprülü managed to attach himself to powerful men and somehow survived their falls without being destroyed himself. Köprülü continued to hold important offices. He eventually rose to the rank of pasha and was appointed the beylerbey (provincial governor) of the Trebizond Eyalet in 1644.[2] Mehmed Pasha's early rise was facilitated by his participation in patronage networks with other Albanians in the Ottoman administration. His main patron was the Albanian Grand Vizier Kemankeş Kara Mustafa Pasha who secured Köprülü Mehmed's appointment as mirahor.[5]

Later he was to rule the provinces of Eğri in 1647, of Karaman in 1648, and of Anatolia in 1650. He served as vizier of the divan for one week in 1652 before being dismissed due to the constant power struggle within the palace.[4] Over the years, Köprülü had cultivated many friendships at the sultan's court, especially with the Queen Mother Turhan Hatice Sultan, mother of the minor sultan Mehmed IV.[2]

In 1656, the political situation in Ottoman Empire was critical. The war in Crete against the Venetians was still continuing. The Ottoman Navy under Kapudan Pasha (grand admiral) Kenan Pasha, in May 1656, was defeated by the Venetian and Maltese navy at the Battle of Dardanelles (1656) and the Venetian navy continued the blockade of the Çanakkale Straits cutting the Ottoman army in Crete from Constantinople, the state capital. There was a political plot to unseat the reigning Sultan Mehmed IV led by important viziers including the Grand Mufti (Şeyhülislam) Hocazade Mesut Efendi. This plot was discovered, and the plotters were executed or exiled. The Mother Sultana Turhan Hatice conducted consultations and the most favored candidate for the post of Grand Vizier came out as the old and retired but experienced Köprülü Mehmed Pasha. Mehmed Efendi, the chief of scribes, and the chief architect convinced the sultan that only Köprülü Mehmed Pasha could avert disaster.[2]

Grand Vizier

Köprülü was called to Istanbul, where he accepted the position of Grand Vizier on 14 September 1656. He spoke to Valide Sultan on his appointment as Grand Vizier and told his terms and she accepted. [4] As a condition of his acceptance, Köprülü demanded that the sultan decree only what Köprülü approved, allow him to make all the appointments and dismissals, refrain from giving the right to execute things to another person, and refuse to hear or accept any malicious stories that might be spread about him. He was given extraordinary powers and political rule without interference, even from the highest authority of the Sultan. Of course, he gave reports on governance to Turhan Sultan, and in many administrative matters she supported him. Thus, historians saw her and him as the mainstay of the Ottoman state.[2]

Köprülü had acquired the reputation of being an honest and able administrator, but he was 80 years old when he assumed office. In order to prevent the Valide Sultan or any other person from the harem from exercising power in their affairs, he proposed to confirm and declare the sultan's adulthood. As the Grand Vizier, his first task was to advise Sultan Mehmed IV to conduct a life of hunts and traveling around the Balkans and to reside in the old capital of Edirne, thus stopping his direct political involvement in the management of the state. On 4 January 1657, the household cavalry Sipahi troops in Constantinople started a rebellion and this was cruelly suppressed by Köprülü Mehmed Pasha with the help of Janissary troops. The Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople was proven to be in treasonous contacts with the enemies of Ottoman state and Köprülü Mehmed Pasha approved of his execution.

Rivals and unfriendly religious leaders were banished or executed. The support of the Janissaries was obtained once he was secure in his office. Köprülü centralized power in the empire, reviving traditional Ottoman methods of governing.[2] He ordered those who were suspected of abusing their positions or who proved to be corrupt to be removed or executed.[2] Those who failed at their tasks were punished severely, and unsuccessful military commanders often paid the supreme price. When Grand Admiral Topal Mehmed Pasha failed to break the Venetian blockade of the Dardanelles on 17 July 1657, Köprülü executed him and his principal officers on the spot. When rivals complained to Mehmed IV about the Grand Vizier's methods, Köprülü resigned, complaining that the Sultan had violated their agreement. Mehmed immediately asked Köprülü to return as Grand Vizier, because his methods showed such success at restoring Ottoman power. The Sultan gave the Grand Vizier the absolute authority over the life and property of the Ottoman government and people and assured him that anyone who opposed him for any purpose could be executed for disobeying the order.[2]

War with Venice

(Pieter_Casteleyn%252C_1657).jpg.webp)

Since the resurgence of the Republic of Venice was the immediate crisis that had prompted Köprülü's appointment as grand vizier, it was important that he demonstrate his effectiveness as a leader against the Venetians. He started on a military expeditions against the Venetian blockade of Dardanelles Straits. The Ottoman navy had a victory against Venice in the Battle of the Dardanelles on 19 July 1657. This allowed Ottomans to regain some of the Aegean islands, including Bozcaada and Limni (15 November) and to open the sea-supply routes to the Ottoman Army still conducting the sieges of Crete.[2]

War with Transylvania and the Habsburgs

In 1658 he conducted a successful campaign in Transylvania. In Transylvania, Prince George II Rákóczi renounced his erstwhile allegiance to the sultan. He attempted to make his state into a major power, allying himself with other Protestant princes in an attempt to conquer Hungary and Poland. While Rákóczi invaded Poland in 1657, however, Köprülü sent the Crimean Tatars to attack Transylvania. They forced Rákóczi to retreat from Poland, but he refused to resume his obedience to the sultan. In response, in 1658, Köprülü himself led a large Ottoman army into Transylvania. This force defeated Rákóczi and forced him to flee to Habsburg lands.[2] War with Habsburgs continued, but Ottoman control over Transylvania was confirmed in a temporary peace. He also annexed Yanova (Jenö) on 1 August 1660 and Várad on 27 August. By annexing more territory in Hungary, he intended to directly threaten the Austrian capital Vienna.

Revolt of Abaza Hasan Pasha

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha's campaign against Transylvania was cut short by the large-scale revolt of several eastern provincial governors under the leadership of Abaza Hasan Pasha, then the governor of Aleppo. The rebels opposed Köprülü Mehmed's violent purges of the military and demanded that he be killed. However, Sultan Mehmed IV remained steadfast in his support for Köprülü and dispatched an army against the rebels under the command of Murtaza Pasha, who was then guarding the Safavid frontier. Despite assembling a force of 30,000 men and defeating Murtaza Pasha in battle, the harsh winter and fading morale eventually forced the rebels to capitulate. Abaza Hasan's revolt was finally brought to an end in February 1659 with the assassination of all the rebel commanders in Aleppo, despite promises that they would be spared.[7]

Ayazmakapi Fire

In July 1660 there was a big fire in Istanbul (the Ayazmakapi Fire) causing great damage to persons and buildings, leading later to a food scarcity and plague. Köprülü Mehmed Pasha became personally involved in the reconstruction affairs. The honesty and integrity in conducting state affairs by Köprülü Mehmed Pasha is shown by an episode in this task.[8] The burnt-out Jewish quarters from the Ayazmakapi Fire were decided to be compulsorily purchased by the state.

Death and legacy

Despite Köprülü's advanced age, he continued to display energy until the end of his life. When he fell mortally ill in 1661, the sultan came to his bedside. Köprülü convinced him to appoint his son, Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed Pasha, as the next grand vizier. He also allegedly advised the sultan never to take advice from a woman, never to appoint a minister who was too wealthy, to always keep the treasury full, and to always keep the army on the move.[2]

Köprülü died on 31 October 1661. He left behind a well-tuned administrative machine, having restored to the Ottoman Empire its reputation for military aggressiveness and its former prestige and power internally and externally.[2] Köprülü Mehmed's victories in Transylvania would push the Ottoman border closer to Austria.[2]

Family

While stationed in Köprü in Anatolia, he married Ayşe Hatun (Hanım), daughter of Yusuf Ağa, a notable originally from Kayacık, a village of Havza in Amasya. Yusuf Ağa was a voyvoda (tax-farmer)[9] who built a bridge in Kadegra, that thus became Köprü, from which the family name of Mehmed (who was originally stationed there, and where he was sanjak-bey)[10] was taken.[10] Together they had a number of children, the best known of whom being Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha.[10]

See also

References

- N. Sakaoğlu (1999), Bu Mülkün Sultanları, İstanbul: Oğlak.

- ↑ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923. Basic Books. pp. 253–4. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Alexander Mikaberidze (22 July 2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World. ISBN 978-1-59884-337-8. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Server Rifat İskit (1960). Resemli-haritalı mufassal Osmanlı tarihi. İskit Yayını. p. 2067.

- 1 2 3 4 Gabor Agoston, Bruce Alan Masters (21 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Wasiucionek 2016, p. 111.

- ↑ Alexander Mikaberidze (22 July 2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 487–. ISBN 978-1-59884-337-8.

- ↑ Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923. Basic Books. pp. 257–62. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- ↑ Sakaoglu, 281

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi; Bruce McGowan; Sevket Pamuk (2011). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 671. ISBN 978-0-521-57455-6.

- 1 2 3 Kenan, Seyfi; Aksin Somel, Selçuk (2021). Dimensions of Transformation in the Ottoman Empire from the Late Medieval Age to Modernity: In Memory of Metin Kunt. Brill. p. 73. ISBN 978-90-04-44235-1.

daughter of a certain Yusuf Ağa, a notable originally from the Kayacik (village) of Havza (town) at Amasya. Yusuf Ağa was the voyvod[a] of Kadegra, a district of Amasya, where Mehmed was sancakbey in 1634, kadegra was named Köprü [from which the Köprülü get their name] after a bridge that Yusuf Ağa constructed

Bibliography

- Wasiucionek, Michal (2016). Politics and Watermelons: Cross-Border Political Networks in the Polish-Moldavian-Ottoman Context in the Seventeenth Century (PDF) (Thesis). European University Institute.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

.svg.png.webp)