| Korean–Jurchen border conflicts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

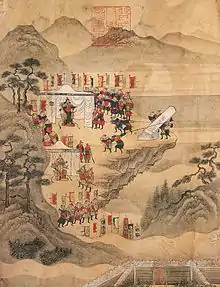

A historical painting depicting the scene of Yun Gwan of Goryeo conquering the Jurchens and erecting a monument to mark the border. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Goryeo[1] Joseon |

Jurchens Jin dynasty Later Jin dynasty | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Yun Gwan Kim Jong-seo |

Wuyashu Amin | ||||||||

The Korean–Jurchen border conflicts were a series of conflicts from the 10th century to the 17th century between the Korean states of Goryeo and Joseon and the Jurchen people.

Background

In 993, the land between the border of Liao and Goryeo was occupied by troublesome Jurchen tribes, but the Goryeo diplomat Seo Hui was able to negotiate with Liao and obtain that land up to the Yalu River, citing that in the past it belonged to Goguryeo, the predecessor to Goryeo.[2][3]

Both Balhae remnants and miscellaneous tribal peoples like Jurchens lived in the area between the Yalu and Daedong rivers which was targeted for annexation by Goryeo.[4]

Goryeo period

The Jurchens in the Yalu River region were tributaries of Goryeo since the reign of Wang Geon, who called upon them during the wars of the Later Three Kingdoms period, but the Jurchens switched allegiance between Liao and Goryeo multiple times, taking advantage of the tension between the two nations; posing a potential threat to Goryeo's border security, the Jurchens offered tribute to the Goryeo court, expecting lavish gifts in return, which was the custom of the sinospheric order at the time.[5]

Joseon period

The Joseon Koreans tried to deal with the Jurchens by using both forceful means and incentives. Sometimes the military was dispatched, in tandem with appeasement with titles and degrees, and allowing them to sell furs for Joseon crops to make up for Jurchens' lack of food. Starting with Lee Ji-ran's recommendation and example, attempts were started to acculturate Jurchens by having Koreans marry them to integrate them into Korea. Despite the tributary relations and gifting and acculturating, many Jurchen tribes were submissive one year and rebellious the next.[6][7] By the 1400s, the Ming Yongle Emperor was determined to wrest the Jurchens out of Korean influence and have China dominate them instead.[8][9]

A key Jurchen leader named Mengtemu (Möngke Temür), chief of the Odoli Jurchens, who had always claimed he had been a servant of the Taejo of Joseon since Taejo's days as a border general of Goryeo, and even following him (Taejo Lee Seong-gye) to his wars, because he fed Mengtemu's family and provided land for him to live during his impoverished youth. Mengtemu was asked by Joseon to reject Ming's overtures, but was unsuccessful since Mengtemu folded and submitted to the Ming in 1412.[10][11][12][13]

Joseon under Sejong the Great engaged in military campaigns against the Jurchen and after defeating the Odoli, Maolian and Udige clans, Joseon managed to take control of Hamgyong. This shaped the modern borders of Korea around 1450, when several border forts were established in the region.[14]

Aftermath

Nurhaci, who was originally a vassalage to the Ming dynasty,[15] made efforts to unify the Jurchen tribes including the Jianzhou, Haixi and Wild Jurchens.[16] He offered the Ming dynasty to sent Jianzhou Jurchen troops into Korea to fight against the Japanese forces during the Japanese invasions of Korea in the 1590s. The Ming dynasty was still fully recognized by Nurhaci as his overlord since he did not send this message to Joseon and only to the Ming. Nurhaci's offer to fight against the Japanese was denied due to misgivings from the Koreans,[17] but the Ming awarded Nurhaci the title of dragon-tiger general (龍虎將軍) along with another Jurchen leader.[18]

Nurhaci later established the Later Jin dynasty and openly renounced Ming overlordship with the Seven Grievances in 1618.[19] A 30,000-strong Jurchen force led by Nurhaci's nephew Amin overran Joseon's defenses during the Later Jin invasion of Joseon in 1627. The Jurchens pushed Joseon to adopt "brotherly relations" with the Later Jin through a treaty. In 1636, Nurhaci's son and Qing emperor Hong Taiji dispatched a punitive expedition to Joseon because Injo of Joseon persisted in his anti-Jurchen (anti-Manchu) policies. Having been defeated, Joseon was compelled to sever ties with the Ming and instead recognized the Qing as suzerain according to the imperial Chinese tributary system.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Hyŏn-hŭi Yi; Sŏng-su Pak; Nae-hyŏn Yun (2005). New history of Korea. Jimoondang. p. 288. ISBN 978-89-88095-85-0.

- ↑ Yun 1998, p.64: "By the end of the negotiation, Sô Hûi had ... ostensibly for the purpose of securing safe diplomatic passage, obtained an explicit Khitan consent to incorporate the land between the Ch’ôngch’ôn and Amnok Rivers into Koryô territory."

- ↑ “自契丹东京至我安北府数百里之地,皆为生女真所据。光宗取之,筑嘉州、松城等城,今契丹之来,其志不过取 北二城,其声言取高勾丽旧地者,实恐我也”(高丽史)

- ↑ Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (25 November 1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ↑ Breuker 2010, pp. 220-221. "The Jurchen settlements in the Amnok River region had been tributaries of Koryŏ since the establishment of the dynasty, when T'aejo Wang Kŏn heavily relied on a large segment of Jurchen cavalry to defeat the armies of Later Paekche. The position and status of these Jurchen is hard to determine using the framework of the Koryŏ and Liao states as reference, since the Jurchen leaders generally took care to steer a middle course between Koryŏ and Liao, changing sides or absconding whenever that was deemed the best course. As mentioned above, Koryŏ and Liao competed quite fiercely to obtain the allegiance of the Jurchen settlers who in the absence of large armies effectively controlled much of the frontier area outside the Koryŏ and Liao fortifications. These Jurchen communities were expert in handling the tension between Liao and Koryŏ, playing out divide-and-rule policies backed up by threats of border violence. It seems that the relationship between the semi-nomadic Jurchen and their peninsular neighbours bore much resemblance to the relationship between Chinese states and their nomad neighbours, as described by Thomas Barfield."

- ↑ Seth 2006, p. 138.

- ↑ Seth 2010, p. 144.

- ↑ Zhang 2008 Archived 2014-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, p. 29.

- ↑ John W. Dardess (2012). Ming China, 1368-1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-4422-0490-4.

- ↑ Goodrich 1976, p. 1066.

- ↑ Peterson 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Twitchett 1998, pp. 286-287.

- ↑ Zhang 2008 Archived 2014-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, p. 30.

- ↑ Haywood, John; Jotischky, Andrew; McGlynn, Sean (1998). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492. Barnes & Noble. p. 3.24. ISBN 978-0-7607-1976-3.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part 1, by Denis C. Twitchett, John K. Fairbank, p. 29

- ↑ Jae-eun Kang (2006). The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism. Homa & Sekey Books. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-1-931907-37-8.

- ↑ Seonmin Kim (19 September 2017). Ginseng and Borderland: Territorial Boundaries and Political Relations Between Qing China and Choson Korea, 1636-1912. Univ of California Press. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-0-520-29599-5.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part 1, by Denis C. Twitchett, John K. Fairbank, p. 30

- ↑ Huiyun Feng (2020). China's Challenges and International Order Transition. University of Michigan Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780472131761.

- ↑ World History. EDTECH. 2018. p. 75. ISBN 9781839472800.

Sources

- History of Goryeo

- Breuker, Remco E. (2010), Establishing a Pluralist Society in Medieval Korea, 918-1170: History, Ideology and Identity in the Koryŏ Dynasty, vol. 1 of Brill's Korean Studies Library, Leiden, South Holland: Brill, pp. 220-221, ISBN 978-9004183254

- Association for Asian Studies. Ming Biographical History Project Committee (1976), Goodrich, Luther Carrington (ed.), Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Columbia University Press, p. 1066, ISBN 023103833X

- Peterson, Willard J., ed. (2002), The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Pt. 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13, 31, ISBN 0-521-24334-3

- Robinson, Kenneth R.. 1992. "From Raiders to Traders: Border Security and Border Control in Early Chosŏn, 1392—1450". Korean Studies 16. University of Hawai'i Press: 94–115. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23720024.

- Seth, Michael J. (2006), A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period Through the Nineteenth Century, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 138, ISBN 978-0-7425-4005-7

- Seth, Michael J. (16 October 2010), A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, p. 144, ISBN 978-0-7425-6717-7

- Rossabi, Morris (1998), "The Ming and Inner Asia", in Denis C. Twitchett; Frederick W. Mote (eds.), The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Pt. 2, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 221–71, ISBN 0521243335

- Yun, Peter I. (1998). Rethinking the Tribute System: Korean States and northeast Asian Interstate Relations, 600-1600 (Ph.D. thesis). University of California, Los Angeles. ISBN 9780599031203..

- Zhang Feng (2008), "Traditional East Asian Structure from the Perspective of Sino-Korean Relations", International Relations Department The London School of Economics and Political Science: 29, 30, archived from the original on 20 April 2014, retrieved 18 April 2014,

Paper presented to ISA's 49th Annual Convention, San Francisco, March 26–29, 2008

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)