Right image: at the top, detail of the Virgin's mantle hem in Antonio Vivarini's Saint Louis de Toulouse, 1450. At the bottom, detail of Virgin's mantle hem in Jacopo Bellini's Virgin of Humility, 1440. Louvre Museum.

Pseudo-Kufic, or Kufesque, also sometimes pseudo-Arabic,[1] is a style of decoration used during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance,[2] consisting of imitations of the Arabic Kufic script, or sometimes Arabic cursive script, made in a non-Arabic context: "Imitations of Arabic in European art are often described as pseudo-Kufic, borrowing the term for an Arabic script that emphasizes straight and angular strokes, and is most commonly used in Islamic architectural decoration".[3] Pseudo-Kufic appears especially often in Renaissance art in depictions of people from the Holy Land, particularly the Virgin Mary. It is an example of Islamic influences on Western art.

Early examples

Abbasid Dinar for comparison:

.JPG.webp)

Some of the first imitations of the Kufic script go back to the 8th century when the English King Offa (r. 757–796) produced gold coins imitating Islamic dinars. These coins were copies of an Abbasid dinar struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur, with "Offa Rex" centred on the reverse. It is clear that the moneyer had no understanding of Arabic as the Arabic text contains many errors. The coin may have been produced in order to trade with Al-Andalus; or it may be part of the annual payment of 365 mancuses that Offa promised to Rome.[4]

In Medieval southern Italy (in merchant cities such as Amalfi and Salerno) from the mid-10th century, imitations of Arabic coins, called tarì, were widespread but only used illegible pseudo-Kufic script.[5][6][7]

Medieval Iberia was especially rich in architectural decorations featuring both pseudo-Kufic and pseudo-Arabic designs,[2] largely because of the presence of Islamic states on the peninsula. The Iglesia de San Román (consecrated in 1221) in Toledo included both (real) Latin and pseudo-Arabic (i.e., not Kufic style) inscriptions as decorative elements. The additions of Pedro I of Castile and León to the Alcazar of Seville (mid-14th century) bear pseudo-Kufic design elements reminiscent of the Alhambra in Granada, and the metal facade of the main doors to the Cathedral of Seville (completed 1506) include arabesque and pseudo-Kufic design elements. Such decorative elements addressed both social realities and aesthetic tastes: The presence of many Arabized Christians in many of these otherwise Christian states, and a general appreciation among the Christian aristocracy for Islamic high culture of the time.

Examples are known of the incorporation of Kufic script and Islamic-inspired colourful diamond-shaped designs such as a 13th French Limoges enamel ciborium at the British Museum.[8] The band in pseudo-Kufic script "was a recurrent ornamental feature in Limoges and had long been adopted in Aquitaine".[9]

Pseudo-Arabic (i.e. not Kufic style) surrounding an interior window of the Church of San Román, Toledo, Spain (c. 1221)

Pseudo-Arabic (i.e. not Kufic style) surrounding an interior window of the Church of San Román, Toledo, Spain (c. 1221).jpg.webp) Decoration from a wall in the Alcázar of Seville (c. 1350), showing a band of pseudo-Kufic decoration meant to mimic decorations in the Alhambra

Decoration from a wall in the Alcázar of Seville (c. 1350), showing a band of pseudo-Kufic decoration meant to mimic decorations in the Alhambra.jpg.webp) Part of the metal facade on the main door to the Cathedral of Seville (c. 1500), showing both arabesque and pseudo-Kufic design elements

Part of the metal facade on the main door to the Cathedral of Seville (c. 1500), showing both arabesque and pseudo-Kufic design elements

Renaissance painting

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Numerous instances of pseudo-Kufic are known from European art from around the 10th to the 15th century. Pseudo-Kufic inscriptions were often used as decorative bands in the architecture of Byzantine Greece from the mid 11th century to mid-12th century, and in decorative bands around religious scenes in French and German wall paintings from the mid-12th to mid-13th century, as well as in contemporary manuscript illuminations.[10] Pseudo-Kufic would also be used as writing or as decorative elements in textiles, religious halos or frames.[11] Many are visible in the paintings of Giotto (c. 1267 – 1337).[3]

From 1300 to 1600, according to Rosamond Mack, the Italian imitations of Arabic script tend to rely on cursive Arabic rather than Kufic, and therefore should better be designated by the more generalist term of "pseudo-Arabic".[3] The habit of representing gilt halos decorated with pseudo-Kufic script seems to have disappeared in 1350, but was revived around 1420 with the work of painters such as Gentile da Fabriano, who was probably responding to artistic influence in Florence, or Masaccio, who was influenced by Gentile, although his own script was "jagged and clumsy", as well as Giovanni Toscani or Fra Angelico, in a more Gothic style.[12]

From around 1450, northern Italian artists also started to incorporate pseudo-Islamic decorative devices in their paintings. Francesco Squarcione started the trend in 1455, and he was soon followed by his main pupil, Andrea Mantegna. In the 1456–1459 San Zeno Altarpiece, Mantegna combines pseudo-Islamic script in halos and garment hems (see detail), to depiction of Mamluk book-bindings in the hand of San Zeno (see detail), and even to a Turkish carpet at the feet of the Virgin Mary (see detail).[13]

The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic or pseudo-Arabic in Medieval or early Renaissance painting is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13-14th century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them:[14] "In Renaissance art, pseudo-Kufic script was used to decorate the costumes of Old Testament heroes like David".[15] Another reason might be that artist wished to express a cultural universality for the Christian faith, by blending together various written languages, at a time when the church had strong international ambitions.[16]

Pseudo-Hebrew is also sometimes seen,[17] as in the mosaic at the back of the abse in Marco Marziale's Circumcision, which does not use actual Hebrew characters.[18] It was especially common in German works.

Finally pseudo-Arabic elements became rare after the second decade of the 16th century.[19] According to Rosamond Mack: "The Eastern scripts, garments, and halos disappeared when the Italians viewed the Early Christian era in an antique Roman context."[19]

Pseudo-Kufic on the veil of the Virgin, Ugolino di Nerio, c. 1315–1320

Pseudo-Kufic on the veil of the Virgin, Ugolino di Nerio, c. 1315–1320 Pseudo-Kufic mantle hem, in Paolo Veneziano's Virgin Mary and Child, 1358. Louvre Museum

Pseudo-Kufic mantle hem, in Paolo Veneziano's Virgin Mary and Child, 1358. Louvre Museum Pseudo-Arabic script in the Virgin Mary's halo, detail of Adoration of the Magi (1423) by Gentile da Fabriano. The script is further divided by rosettes like those on Mamluk dishes.[20]

Pseudo-Arabic script in the Virgin Mary's halo, detail of Adoration of the Magi (1423) by Gentile da Fabriano. The script is further divided by rosettes like those on Mamluk dishes.[20]

Pseudo-Arabic on the Christ Child's blanket, by Gentile da Fabriano[22]

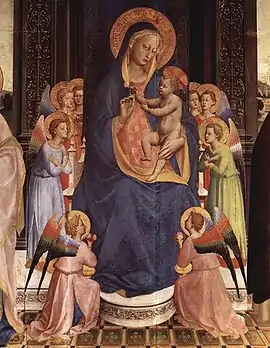

Pseudo-Arabic on the Christ Child's blanket, by Gentile da Fabriano[22] Virgin with a Gothicizing pseudo-Arabic halo, by Fra Angelico (c. 1428–1430)

Virgin with a Gothicizing pseudo-Arabic halo, by Fra Angelico (c. 1428–1430) The Virgin Mary in Andrea Mantegna's San Zeno Altarpiece combines pseudo-Arabic halos and garment hems, with a Turkish carpet at her feet (c. 1456–1459).

The Virgin Mary in Andrea Mantegna's San Zeno Altarpiece combines pseudo-Arabic halos and garment hems, with a Turkish carpet at her feet (c. 1456–1459).

Gallery

Pseudo-Kufic on garments in Henri Bellechose's Le Retable de Saint Denis, c. 1415–1416

Pseudo-Kufic on garments in Henri Bellechose's Le Retable de Saint Denis, c. 1415–1416 Virgin of Humility, adored by a prince of the House of Este by Jacopo Bellini, 1440, with pseudo-Kufic mantle hem, but halo in Roman script. Louvre Museum

Virgin of Humility, adored by a prince of the House of Este by Jacopo Bellini, 1440, with pseudo-Kufic mantle hem, but halo in Roman script. Louvre Museum Pseudo-Kufic halo, in Antonio Vivarini's Saint Louis de Toulouse, 1450. Louvre Museum

Pseudo-Kufic halo, in Antonio Vivarini's Saint Louis de Toulouse, 1450. Louvre Museum Pseudo-Kufic hem in Giovanni Bellini's Le Christ Bénissant, c. 1465–1470. Louvre Museum

Pseudo-Kufic hem in Giovanni Bellini's Le Christ Bénissant, c. 1465–1470. Louvre Museum Early-16th-century Andalusian dish with pseudo-Arabic script around the edge, excavated in London. Museum of London

Early-16th-century Andalusian dish with pseudo-Arabic script around the edge, excavated in London. Museum of London

Pseudo-Hebrew

.jpg.webp) Pseudo-Hebrew script on the bustier of Jan van Scorel's Maria Magdalena, 1530

Pseudo-Hebrew script on the bustier of Jan van Scorel's Maria Magdalena, 1530

See also

Notes

- ↑ Robbert Woltering (2011), "Pseudo-Arabic", in Lutz Edzard and Rudolf de Jong (eds.), Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics (Brill), consulted online on 14 October 2023.

- 1 2 Encyclopaedia Britannica. Beautiful Gibberish: Fake Arabic in Medieval and Renaissance Art

- 1 2 3 Mack, p.51

- ↑ Medieval European Coinage by Philip Grierson p.330

- ↑ Cardini, p.26

- ↑ Grierson, p.3

- ↑ Matthew, p.240

- ↑ British Museum exhibit

- 1 2 Louvre museum notice Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mack, p.68

- ↑ "Beautiful Gibberish: Fake Arabic in Medieval and Renaissance Art". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ↑ Mack, p.64-66

- ↑ Mack, p.67

- ↑ Mack, p.52, p.69

- ↑ Freider. p.84

- ↑ "Perhaps they marked the imagery of a universal faith, an artistic intention consistent with the Church's contemporary international program." Mack, p.69

- ↑ Mack, p. 62

- ↑ National Gallery, image Archived 2009-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Mack, p.71

- ↑ Mack, p.65-66

- ↑ Mack, p.66

- ↑ Mack, p.61-62

References

- Braden K. Frieder Chivalry & the perfect prince: tournaments, art, and armor at the Spanish Habsburg court Truman State University, 2008 ISBN 1-931112-69-X, ISBN 978-1-931112-69-7

- Cardini, Franco. Europe and Islam. Blackwell Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-0-631-22637-6

- Grierson, Philip Medieval European Coinage Cambridge University Press, 2007 ISBN 0-521-03177-X, ISBN 978-0-521-03177-6

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-1

- Matthew, Donald, The Norman kingdom of Sicily Cambridge University Press, 1992 ISBN 978-0-521-26911-7