Poltava

Полтава | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) %252C_%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0._%D0%A4%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE_%D0%B2_%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%85_%D1%83%D0%BA%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%97%D0%BD%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%83.jpg.webp)  Top left: Poltava Regional Museum, Top right: Poltava Holy Cross Monastery, Center: The Round Square, Bottom left: The White Arbor, Bottom right: Assumption Cathedral | |

Flag  Coat of arms Logo | |

Poltava Location of Poltava in Poltava Oblast.  Poltava Poltava (Ukraine) | |

| Coordinates: 49°35′22″N 34°33′05″E / 49.58944°N 34.55139°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Founded | 8991 |

| Raions | 3 raions (districts)

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 103 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 279,593 |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 36000—36499 |

| Area code | +380-532(2) |

| Licence plate | CK, BI |

| Sister cities | Filderstadt, Ostfildern, Veliko Tarnovo, Lublin, Nice |

| Website | rada-poltava |

| 1 The previously believed foundation date was 1174. | |

Poltava (UK: /pɒlˈtɑːvə/,[1] US: /pəlˈ-/;[2][3] Ukrainian: Полтава, IPA: [polˈtɑwɐ]) is a city located on the Vorskla River in central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Poltava Oblast as well as Poltava Raion within the oblast. It also hosts the administration of Poltava urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[4] Poltava has a population of 279,593 (2022 estimate).[5]

History

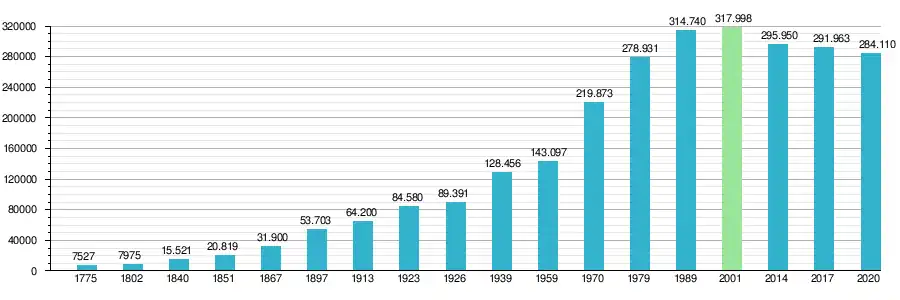

It is still unknown when Poltava was founded, although the town was not attested before 1174. However, for reasons unknown, municipal authorities chose to celebrate the city's 1100th anniversary in 1999. The settlement is indeed an old one, as archeologists unearthed an ancient Paleolithic dwelling, as well as Scythian remains, within the city limits.

Middle Ages

The present name of the city is traditionally connected to the settlement Ltava, which is mentioned in the Hypatian Chronicle in 1174.[6][7] According to the chronicle, on Saint Peter's Day (12 July) of 1182, Igor Sviatoslavich, chasing hordes of the Cuman khans Konchak and Kobiak, crossed the Vorskla River near Ltava and moved towards Pereiaslav), where Igor's army was victorious over the Cumans.[6] During the Mongol invasion of Rus' in 1238–39, many cities of the middle Dnipro region were destroyed, possibly including Ltava.[6]

In the mid-14th century the region was part of the Duchy of Kyiv, which was a vassal of the Algirdas' Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[6] According to the Russian historian Aleksandr Shennikov, the region around modern Poltava was a Cuman Duchy belonging to Mansur, who was a son of Mamai.[8] Shennikov also claims that the Mansur Duchy joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as an associated state rather than a vassal state, and that the city of Poltava already existed at that time.[8] In 1399, Mansur's army assisted the Grand Ducal Lithuanian Army in the battle of the Vorskla River. According to legend, after the battle, the Cossack Mamay helped Vytautas to escape death.[8]

The city is mentioned for the first time under the name of Poltava no later than 1430.[6] Supposedly, in 1430 the Lithuanian duke Vytautas gave the city, along with Glinsk (today a village near the city of Romny) and Glinitsa, to Murza Olexa (Loxada Mansurxanovich), who moved to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Golden Horde.[6] In 1430 Murza Olexa was baptized as Alexander Glinsky, who was a progenitor of the Glinsky family.[6] According to Shenninkov, Alexander Glinsky must have been baptized in 1390 by Cyprian, Metropolitan of Kyiv, who had just regained his title of Metropolitan of Kyiv and all Russia (rather than the Metropolitan of Russia Minor and Lithuania). On 6 March 1390 Cyprian permanently moved to Muscovy.[8]

In 1482, Poltava was razed by the Crimean Khan Mengli I Giray.[6]

Early modern period

In 1537 Ografena Vasylivna Glinska (Baibuza) passed Poltava to her son-in-law Mykhailo Ivanovych Hrybunov-Baibuza.[6]

After the Union of Lublin in 1569, the territory around Poltava became part of the Crown of Poland. In 1630 Poltava was passed to a Polish magnate, Bartholomew Obalkowski.[6] In 1641 it changed ownership again, to Alexander Koniecpolski.[6] In 1646 Poltava became part of Wiśniowiecki Ordynatsia (a large Wiśniowiecki estate in Left-bank Ukraine centered in Lubny), governed by the Ruthenian-Polish magnate Jeremi Wiśniowiecki (1612–51).[6]

In 1648, the city became the base of a distinguished regiment of Ukrainian Cossacks, and served as a Cossack stronghold during the Khmelnytsky Uprising.[6] In 1650, to commemorate a victory of the Cossack Host over the Polish army at the Poltavka River, the Metropolitan of Kyiv, Sylvester Kossov, ordered the establishment of the monastery of the Exaltation of the Cross in Poltava. The project was financed by a number of prominent local residents, including Martyn Pushkar, Ivan Iskra, Ivan Kramar and many others.[6]

During the 1654 Pereyaslav Council, the Poltava city delegates pledged their allegiance to the Czar of Muscovy, after which stolnik Andrei Spasitelev arrived in Poltava and recorded 1,335 residents who had pledged their allegiance.[6] In 1658 Poltava became a center of anti-government revolt led by Martyn Pushkar, who contested the legitimacy of Ivan Vyhovsky's election to the post of Hetman of Zaporizhian Host.[6] The uprising was extinguished with the help of Crimean Tatars.[6]

On the issue boyar Vasily Borisovich Sheremetev wrote to Alexei Mikhailovich on 8 June 1658: "... the Cherkas [Cossack] city of Poltava is ravaged and burned to the ground and only if the Great Sovereign orders to rebuilt on the Tatar Sokma (pathway) of Bakeyev Route and protect many his sovereign cities from Tatar visits. And if the Great Sovereign allows to place a voivode in the city and rebuilt the city until the fall that in Plotava Cherkasy [Cossacks] and residents built their houses and stock-piled their food".[6] With the signing of the 1667 truce of Andrusovo, the city was finally subjected to the Tsardom of Muscovy, while remaining part of the Cossack Hetmanate.

The city suffered from the Great Turkish War when in 1695 Petro Ivanenko led an anti-Muscovite uprising with the help of Crimean Tatars, who ravaged the local monastery.[6] The same year the Poltava Regiment actively participated in the Azov campaigns which resulted in the taking of the Turkish fortress of Kyzy-Kermen (today the city of Beryslav, Kherson Oblast).[6] On 8 July (New Style) or 27 June (Old Style) 1709 the Battle of Poltava took place near the city during the Great Northern War. The battle ended in a decisive victory of Peter I of Russia over the Swedish forces and had great historical importance for the Russians.[6] In 1710 there was a plague in the city and its surrounding area.[6] In the mid-18th century the Kolomak Woods near Poltava became a base of haidamaks (Cossack paramilitary bands).[6]

By 1770, Poltava had several brick factories, a regimental doctor, and a pharmacy; that same year the city conducted four fairs.[6] In 1775 it became a city of Novorossiysk Governorate, guarded by the 8th Company of the Dnieper Pike Regiment headquartered in Kobeliaky.[6] In 1775 Poltava's Monastery of the Exaltation of the Cross (Russian: Крестовоздвиженский монастырь, Krestovozdvizhensky Monastyr) became the seat of bishops of the newly created Eparchy (Diocese) of Slaviansk and Kherson. This large new diocese included the lands of the Novorossiya Governorate and the Azov Governorate north of the Black Sea.[9][10]

Since much of that area had only recently been seized from the Ottoman Empire by Russia, and a large number of Orthodox Greek settlers had been invited to settle in the region, the imperial government selected a renowned Greek scholar, Eugenios Voulgaris, to preside over the new diocese. After his retirement in 1779, he was replaced by another Greek theologian, Nikephoros Theotokis.[9][10]

In 1779 the city established the Poltava county school, which became its first secular educational institution.[6] In 1787 Catherine the Great stopped in Poltava on the way from Crimea, escorted by Grigori Potemkin, Alexander Suvorov and Mikhail Kutuzov.[6] In Poltava, on 7 June 1787, before another Russo-Turkish War, Potemkin received his title "Prince of Taurida", while Suvorov received a snuffbox with monogram.[6] In 1802 the city became the seat of the newly established Poltava Governorate.[6] The city's population in 1802 consisted of some 8,000 residents.[6] That same year Poltava opened a government-funded hospital of 20 beds.[6]

19th century

.jpg.webp)

On 2 February 1808, the Poltava Male Gymnasium was established.[6] On 20 June 1808 some 54 families of craftsmen were invited to the city from German principalities and settled in the newly established German Sloboda neighborhood with about 50 clay-made houses.[6] In 1810 there were 8,328 people living in Poltava;[6] that same year, the city's first theater was built.[6] In August 1812, on orders of Little Russia Governor General Lobanov-Rostovsky, the famed Ukrainian writer and statesman Ivan Kotlyarevsky formed the 5th Poltava Cavalry Cossack Regiment.[6]

By 1860, Poltava had around 30,000 inhabitants, a district school, a gymnasium, an Institute for Noble Maidens, a spiritual academy, a cadet corps, a library and a number of schools. In 1870 a railway station was opened, leading to rapid economic growth in the region. However, by 1914 the Population of Poltava (around 60,000) was mostly working in small enterprises. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Poltava became an important cultural centre, where many representatives of Ukrainian national revival were active.

20th century

During the events of 1917–1920, Poltava was under the rule of a number of governments, including the Central Rada, Hetmanate, Ukrainian People's Republic, White Movement and Bolsheviks. From 1918 to 1919 there was Occupation of Poltava by the Bolsheviks. After becoming a part of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Poltava experienced accelerated industrial growth, and its population increased to 130,000 by 1939.

In World War II, the Nazi Wehrmacht occupied Poltava from 18 September 1941 until 23 September 1943, when it was retaken during the Chernigov-Poltava Strategic Offensive of the Battle of the Dnieper. During the Nazi occupation the Jewish population (9.9% of the total population in 1939) was imprisoned in a ghetto before being murdered during mass executions perpetrated by an Einsatzgruppe and buried in mass graves in the area.[11]

By the summer of 1944, the United States Army Air Forces conducted a number of shuttle bombing raids against Nazi Germany under the name of Operation Frantic. Poltava Air Base, as well as Myrhorod Air Base, were used as eastern locations for landing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers involved in those operations.

The post-war restoration of Poltava continued in the 1950s and 1960s. The city became an important centre of military education in the Soviet Union, where missile and communications officers were prepared, and was also home to a Soviet Air Force division of heavy bombers.

Until 18 July 2020, Poltava was designated as a city of oblast significance and did not belong to Poltava Raion even though it was the center of the raion. As part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Poltava Oblast to four, the city was merged into Poltava Raion.[12][13]

Population

Language

Distribution of the population by native language according to the 2001 census:[14]

| Language | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 85.39% |

| Russian | 14.06% |

| other/undecided | 0.55% |

According to a survey conducted by the International Republican Institute in April-May 2023, 75 % of the city's population spoke Ukrainian at home, and 12 % spoke Russian.[15]

Geography

Climate

Poltava has a warm-summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with four distinct seasons, it is one of the coldest cities in Ukraine. The annual precipitation is fairly evenly distributed, with the highest concentration in summer, and which falls as snow in winter.[16][17][18]

| Climate data for Poltava (1991–2020, extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.2 (95.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26.0) |

−29.1 (−20.4) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−21.5 (−6.7) |

−28.6 (−19.5) |

−32.2 (−26.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.7 (1.64) |

34.6 (1.36) |

37.5 (1.48) |

39.3 (1.55) |

53.0 (2.09) |

72.7 (2.86) |

69.0 (2.72) |

42.9 (1.69) |

54.1 (2.13) |

50.7 (2.00) |

45.2 (1.78) |

41.8 (1.65) |

582.5 (22.93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.6 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 9.0 | 7.7 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 90.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.9 | 82.5 | 76.4 | 64.8 | 61.3 | 67.2 | 66.7 | 63.1 | 70.5 | 77.4 | 85.9 | 86.6 | 74.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68 | 76 | 132 | 183 | 266 | 293 | 301 | 285 | 215 | 144 | 59 | 42 | 2,064 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (humidity and precipitation 1981–2010; sun 1961–1990)[20][21] | |||||||||||||

Government and subdivisions

Poltava is the administrative center of the Poltava Oblast (province) as well as of the Poltava Raion housed within the city. However, Poltava is a city of oblast subordinance, thus being subject directly to the oblast authorities rather to the raion administration housed in the city itself.

Poltava's government consists of the 50-member Poltava City Council (Ukrainian: Полтавська Міська рада) which is headed by the Secretary (currently Oleksandr Kozub). The city's current mayor is Oleksandr Mamay, who was sworn in on 4 November 2010 after being elected with more than 61 percent of the vote.[22] In 2015 he was re-elected as a candidate of Conscience of Ukraine with 62.9% in a second round of Mayoral election.[23]

The territory of Poltava is divided into 3 administrative raions (districts):[24]

- Shevchenkivsky Raion,[25][26] to the south-west with an area of 2077 hectares and a population of 147,600 in 2005. It is a largely residential area and includes the city centre.

- Kyivsky Raion,[27] is the largest by area, comprising 5437 hectares, or 52.8% of the city total situated in the north and north-west. Its census in 2005 was 111,900. This district has a large industrial zone.

- Podilsky Raion,[28] to the east and south-east, in the valley of the Vorskla river, with an area of 2988 hectares and a population of 53,700 in 2005.

The village of Rozsoshentsi, Scherbani, Tereshky, Kopyly and Suprunivka are officially considered to be outside the city, but constitute part of the Poltava agglomeration.

Culture

The centre of the old city is a semicircular Neoclassical square with the Tuscan column of cast iron (1805–11), commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Poltava and featuring 18 Swedish cannons captured in that battle. As Peter the Great celebrated his victory in the Saviour church, this 17th-century wooden shrine was carefully preserved to this day. The five-domed city cathedral, dedicated to the Exaltation of the Cross, is a superb monument of Cossack Baroque, built between 1699 and 1709. As a whole, the cathedral presents a unity which even the Neoclassical belltower has failed to mar. Another frothy Baroque church, dedicated to the Dormition of the Theotokos, was destroyed in 1934 and rebuilt in the 1990s.

A minor planet 2983 Poltava discovered in 1981 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named after the city.[29]

Sports

The most popular sport is football (soccer). Two professional football teams are based in the city: Vorskla Poltava in the Ukrainian Premier League and FC Poltava in the Second League. There are 3 stadiums in Poltava: Butovsky Vorskla Stadium (main city stadium), Dynamo Stadium are situated in the city centre and Lokomotiv Stadium which is situated in Podil district.

Notable people

- Marie Bashkirtseff (1858–1884) Parisian painter and diarist.[30]

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (1884–1963) historian, longest-serving President of Israel from 1952 to 1963.

- Hanka Bielicka (1915–2006) a Polish singer and actress, known by the name Hanna

- Oleksandr Bilash (1931–2003) composer of lyric songs, ballads, operas, operettas and oratorios

- Sofya Bogomolets (1856–1892) a Russian revolutionary and political prisoner.

- Boris Brasol (1885-1963), lawyer and literary critic and a White Russian immigrant to the United States.

- Moura Budberg (1892–1974), a Russian adventuress and suspected double agent of OGPU & MI6.

- Nat Carr (1886–1944) an American character actor of the silent and early talking picture eras.

- Gregori Chmara (1878–1970) a stage and film actor whose career spanned six decades.

- Marusia Churai (1625–1653) a semi-mythical Ukrainian Baroque composer, poet, and singer.

- Andriy Danylko (born 1973) stage name Verka Serduchka; a Ukrainian comedian, actor, and singer.

- Sam Dreben (1878–1925), a highly decorated soldier in the US Army and a mercenary

- Vladimir Gajdarov (1893–1978) a Russian film actor and star of Russian and German silent cinema.

- Yuliy Ganf (1898–1973) a graphic artist, caricaturist, illustrator and poster designer.

- Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), a novelist, short story writer and playwright.[31]

- Alexander Gurwitsch (1874–1954) biologist and medical scientist; originated Morphogenetic field theory

- Oksana Ivanenko (1906-1997) – Ukrainian children's writer and translator

- Vladimir Ivashko (1932-1994), politician, acting General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Philip Jaffe (1895–1980) a left-wing American businessman, editor and author.

- Ernst Jedliczka (1855–1904) a Russian-German pianist, piano pedagogue, and music critic.

- Mykola Karpov (1929–2003), Ukrainian playwright.

- Dmitri Kessel (1902–1995), photojournalist, Life magazine 1944–1972 and war correspondent

- Vera Kholodnaya (1893–1919) an actress of the early Imperial Russian cinema.

- Yuri Kondratyuk (1897–1942), astronautics and spaceflight pioneer; foresaw reaching the Moon

- Ivan Kotliarevsky (1769–1838) a Ukrainian writer, poet and playwright and social activist

- Anatoly Lunacharsky (1875–1933) Russian Marxist revolutionary; Bolshevik Soviet people's Commissar

- Anton Makarenko (1888–1939), educator, social worker and writer and top educational theorist

- Yuri Levitin (1912–1993) a Soviet Russian composer of classical music.

- Mykola Lysenko (1842–1912) composer, pianist, conductor; founder first Ukrainian classical music school

- Patriarch Mstyslav (1898–1993), Ukrainian Orthodox Church hierarch

- Matvei Muranov (1873–1959) a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician and statesman.

- Panas Myrny (1849-1920) a Ukrainian prose writer and playwright

- Jensen Noen (born 1987) a Los Angeles-based filmmaker, cinematographer and writer.

- Oleksiy Onyschenko (born 1933) a philosopher, academic and culture theorist

- Mikhail Ostrogradsky (1801–1862), a Ukrainian mathematician, mechanic and physicist

- Olena Pchilka (1849–1930), a Ukrainian publisher, writer, ethnographer and civil activist.

- Ivan Paskevich (1782-1856), Ukrainian military leader in Imperial Russian service.[32]

- Symon Petliura (1879–1926) a Ukrainian politician, journalist and military leader of Ukraine's struggle for independence following the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917.

- Zhanna Prokhorenko (1940–2011) a Soviet and Russian actress

- Sasha Putrya (1977–1989) Ukrainian artist, died aged 11 from leukemia.

- Svitlana Pyrkalo (born 1976) a London-based writer, journalist and former BBC radio producer

- Boris Schwanwitsch (1889–1957) a Russian entomologist who specialised in Lepidoptera.

- Moshe Zvi Segal (1904–1985), rabbi and activist in Israeli organizations, including Etzel and Lechi.

- Bert Shefter (1902–1999) a film composer who worked primarily in America.

- Avraham Shlonsky (1900–1973), Israeli poet and editor

- Hryhorii Skovoroda (1722–1794) a Ukrainian poet, philosopher and composer

- Ivan Steshenko (1873–1918), a Ukrainian civic and political activist, writer and Govt. minister.

- Maria Tarnowska (1877–1949), femme fatale, famously convicted of murder in Venice in 1910.

- Elias Tcherikower (1881–1943), a Jewish historian of Judaism and the Jewish people.

- Alina Treiger (born 1979) the first female rabbi to be ordained in Germany since WWII.

- Yelena Ubiyvovk (1918–1942) a partisan and leader of a Komsomol cell during WWII.

- Paisius Velichkovsky (1722–1794), Eastern Orthodox monk and theologian, promoted staretsdom

- Nikolai Yaroshenko (1846–1898) a Ukrainian painter of portraits, genre paintings and drawings.

Sport

- Leonid Bartenyev (1933–2021) a 100 metre team silver medallist at the 1956 and 1960 Summer Olympics

- Sergei Diyev (born 1958) a Russian football manager and former player with over 600 club caps

- Serhiy Konovalov (born 1972) a football coach and former footballer with 270 club caps and 22 for Ukraine

- Oleksandr Melaschenko (born 1978) a football striker with over 320 club caps and 16 for Ukraine

- Ruslan Rotan (born 1981) a former professional footballer with 382 club caps and 100 for Ukraine; now manager of the Ukraine national under-21 football team

- Ivan Shariy (born 1957) is a former Soviet and Ukrainian footballer with over 500 club caps

Economy and infrastructure

Transportation

Poltava's transportation infrastructure consists of two major train stations with railway links to Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kremenchuk. Poltava's Kyiv line is electrified and is used by the Poltava Express. The electrification of the Poltava-Kharkiv line was completed in August 2008.[33]

The Avtovokzal serves as the city's intercity bus station. Buses for local municipal routes depart from "AC-2" (autostation No. 2 – along Shevchenko street) and "AC-3" (Zinkivska street). Local municipal routes are parked along the Taras Shevchenko Street. Marshrutka minibuses serve areas where regular bus access is unavailable; however, they are privately owned and cost more per ride. In addition, a 10-route trolleybus network of 72.6 kilometres (45.1 mi) runs throughout the city. On the routes of the city go more than 50 units of trolleybuses.

Poltava is also served by an International Airport, situated outside the city limits near the village of Ivashky. The international highway M03, linking Poltava with Kyiv and Kharkiv, passes through the southern outskirts of the city. There is also a regional highway P-17 crossing Poltava and linking it with Kremenchuk and Sumy.[34]

Education

Poltava has always been one of the most important science and education centres in Ukraine. Major universities and institutions of higher education include the following:

- Poltava National Pedagogical University Archived 2 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine named after V. G. Korolenko

- National University "Yuri Kondratyuk Poltava Polytechnic"

- Poltava Agrarian State Academy

- Poltava State Medical University

- Poltava University of Economics and Trade

- Poltava Military Institute of Connections

- Poltava Law Institute of Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University Archived 14 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Poltava branch of the State Academy of Statistics, region and audit to the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine

Astronomy

- Poltava gravimetric observatory (PGO) is situated a bit north from city centre (27–29 Miasoyedov St.). Its main work directions are measurements of Earth rotation, latitude variations (applying zenith stars observations, lunar occultation observations and other)

- Observational station of PGO in rural area, some 20 km east along the M03-E40 highway. Radiotelescope URAN-2 (Ukrainian: УРАН-2) is situated there too.

Twin towns – sister cities

Poltava is twinned with:

Gallery

Building of the Noble Assembly

Building of the Noble Assembly State administrative building (Russian Empire)

State administrative building (Russian Empire) Church of the Savior

Church of the Savior Poltava Theatre of Music and Drama

Poltava Theatre of Music and Drama Merchant Ginzburg's "Grand Hotel"

Merchant Ginzburg's "Grand Hotel" Obelisk at the Ivan Kotlyarevsky's burial

Obelisk at the Ivan Kotlyarevsky's burial Moorish-styled mansion of Bakhmatsky

Moorish-styled mansion of Bakhmatsky Exaltation of the Cross nunnery

Exaltation of the Cross nunnery.JPG.webp) Traditional Ukrainian well, krynytsia (Kotlyarevsky's estate)

Traditional Ukrainian well, krynytsia (Kotlyarevsky's estate) Former Regional Administration building

Former Regional Administration building Former Institute of Noble Maidens (today - National Technical University)

Former Institute of Noble Maidens (today - National Technical University)%252C.jpg.webp) Mass burial of 1345 Russian soldiers (perished at the Battle of Poltava)

Mass burial of 1345 Russian soldiers (perished at the Battle of Poltava) Main pedestrian street of Poltava

Main pedestrian street of Poltava State security office

State security office Round square in central Poltava

Round square in central Poltava

References

- ↑ "Poltava". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ↑ "Poltava". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ↑ "Poltava". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ↑ "Полтавская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- ↑ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Poltava: chronicles of the most important events. "History of Poltava" website.

- ↑ Antipovich, G., Buryak, Voloskov, V., others. Poltava: a book for tourists. Ed.2. "Prapor". Kharkiv, 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 Duchy of the Mamai's descendants. Zarusskiy.org. 29 June 2008

- 1 2 Евгений Булгарис (Eugenios Voulgaris's biography) (in Russian)

- 1 2 Никифор Феотоки (Nikephoros Theotoki's biography) (in Russian)

- ↑ "The Untold Stories. The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR". yadvashem.org. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України. 17 July 2020.

- ↑ https://socialdata.org.ua/projects/mova-2001/

- ↑ "Municipal Survey 2023" (PDF). ratinggroup.ua. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ↑ "Poltava, Ukraine Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ "Climate in Poltava, Ukraine". Worlddata.info. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ "Climate Poltava Oblast: Temperature, climate graph, Climate table for Poltava Oblast - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Погода и Климат – Климат Полтава [Weather and Climate – The Climate of Poltava] (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ↑ "Poltava Climate Normals 1961–1990". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ "Oleksandr Mamay won at the elections for the mayor of Poltava" (in Ukrainian). Dzerkalo Tyzhnya. 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Mamai reelected as Poltava mayor – election commission, Interfax-Ukraine (16 November 2015)

- ↑ "Poltavska Oblast, city of Poltava (raion councils of the cities)" (in Ukrainian). Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ "Official resource" (in Ukrainian). Oktiabrskyi Raion Council of Poltava. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ "Information of the Oktiabrskyi Raion of Poltava" (in Ukrainian). Poltava City Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ "Information of the Kyivskyi Raion of Poltava" (in Ukrainian). Poltava City Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ "Information of the Leninskyi Raion of Poltava" (in Ukrainian). Poltava City Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 246. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ↑ Karageorgevitch, Bojidar (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). p. 466.

- ↑ Shedden-Ralston, William Ralston (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). pp. 190–191.

- ↑ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 883–884.

- ↑ "Poltava-Kharkiv rail line" (in Russian). Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ↑ Poltava – Plan. Kyiv Army-Cartographic Fabric.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 13–14.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). p. 13.

- "Official website" (in Ukrainian). Poltava City Council. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- "News" (in Ukrainian). Poltava Oblast State Administration. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- "Poltava Istoricheskaya5" (in Russian). poltavahistory.inf.ua.

- "Main" (in Russian). Transport of Poltava (unofficial project). Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- "Photos of Poltava" (in Russian).

- The murder of the Jews of Poltava during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.