| Wentworth Woodhouse | |

|---|---|

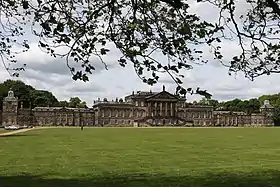

East front of Wentworth Woodhouse (May 2015) | |

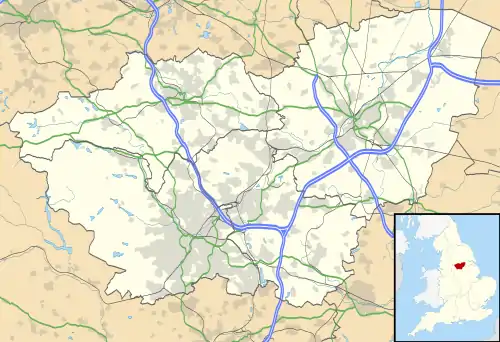

Location within South Yorkshire | |

| General information | |

| Status | Under restoration |

| Type | Stately home |

| Architectural style |

|

| Location | Wentworth, South Yorkshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°28′27″N 1°24′17″W / 53.47417°N 1.40472°W |

| Owner | Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 5 |

| Floor area | 250,000 sq ft (23,000 sq m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | More than 300 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 29 April 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1132769[1] |

| Designated | 1 June 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1001163[2] |

Wentworth Woodhouse is a Grade I listed country house in the village of Wentworth, in the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, England. It is currently owned by the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust.[3] The building has more than 300 rooms, with 250,000 square feet (23,000 m2) of floorspace,[4] including 124,600 square feet (11,580 m2) of living area. It covers an area of more than 2.5 acres (1.0 ha), and is surrounded by a 180-acre (73 ha) park, and an estate of 15,000 acres (6,100 ha).

The original Jacobean house was rebuilt by Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Marquess of Rockingham (1693–1750), and vastly expanded by his son, the 2nd Marquess, who was twice Prime Minister, and who established Wentworth Woodhouse as a Whig centre of influence.[5] In the 18th century, the house was inherited by the Earls Fitzwilliam and the family of the last earl owned it until 1989. It now belongs to the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust and is undergoing restoration.

History

The English Baroque, brick-built, western range of Wentworth Woodhouse was begun in 1725 by Thomas Watson-Wentworth, (after 1728 Lord Malton)[6] after he inherited it from his father in 1723. It replaced the Jacobean structure that was once the home of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, whom Charles I sacrificed in 1641 to appease Parliament. The builder to whom Wentworth's grandson turned for a plan for the grand scheme that he intended[7] was a local builder and country architect, Ralph Tunnicliffe,[8] who had a practice in Derbyshire and South Yorkshire. Tunnicliffe was pleased enough with this culmination of his provincial practice to issue an engraving signed "R. Tunniclif, architectus"[9] which must date before 1734, as it is dedicated to Baron Malton, Watson-Wentworth's earlier title.[9] However the Baroque style was disliked by Whigs, and the new house was not admired. In c. 1734, before the West Front was finished, Wentworth's grandson Thomas Watson-Wentworth commissioned Henry Flitcroft to build the East Front "extension", in fact a new and much larger house, facing the other way, southeastward. The model they settled on was Colen Campbell's Wanstead House, illustrated in Vitruvius Britannicus in 1715.

That same year the rebuilding was already well underway. In a letter from the amateur architect Sir Thomas Robinson of Rokeby to his father-in-law Lord Carlisle of 6 June 1734, Sir Thomas reports that he found the garden front "finished" and that a start had been made on the main front: "when finished 'twill be a stupendous fabric, infinitely superior to anything we have now in England", and he adds "The whole finishing will be entirely submitted to Lord Burlington, and I know of no subject's house in Europe will have 7 such magnificent rooms so finely proportioned as these will be."[10] In the 20th century, Nikolaus Pevsner would agree,[11] but the mention of the architect-earl Burlington, arbiter of architectural taste, boded ill for the provincial surveyor-builder, Tunnicliffe. It is doubtless to Burlington's intervention that about this time, before the West Front was finished, the Earl of Malton, as he had now become, commissioned Henry Flitcroft to revise Tunnicliffe's plan there and build the East Front range. Flitcroft was Burlington's professional architectural amanuensis— "Burlington Harry" as he was called; he had prepared for the engravers the designs of Inigo Jones published by Burlington and William Kent in 1727, and in fact Kent was also called in for confabulation over Wentworth Woodhouse, mediated by Sir Thomas Robinson,[12] though in the event the pedestrian Flitcroft was not unseated and continued to provide designs for the house over the following decade: he revised and enlarged Tunnicliffe's provincial Baroque West Front and added wings, as well as temples and other structures in the park. Contemporary engravings of the grand public East Front give Flitcroft as architect. Flitcroft, right-hand man of the architectural dilettanti and fully occupied as well at the Royal Board of Works, could not constantly be on-site, however: Francis Bickerton, surveyor and builder of York, paid bills in 1738 and 1743.

The grand East Front is the more often illustrated. The West front, the "garden front" that Sir Thomas Robinson found to be finished in 1734, is the private front that looked onto a giardino segreto between the house front and the walled kitchen garden, intended for family enjoyment rather than social and political ambitions expressed in the East Front.[13] Most remnants of it were redesigned in the 19th century.[14]

Wentworth Woodhouse was inherited by Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, briefly Prime Minister in 1765–66 and again in 1782. He received Benjamin Franklin here in 1771. The architect he employed at the house was John Carr of York, who added an extra storey to parts of the East Front and provided the porticoes to the matching wings, each the equivalent of a moderately grand country house. James "Athenian" Stuart contributed designs for panels in the Pillared Hall.[15] The Whistlejacket Room was named for George Stubbs' portrait that hung in it of Whistlejacket, one of the most famous racehorses of all time.[16] The additions were completed in 1772. The second Marquess envisaged a sculpture gallery at the house, which never came to fruition; four marbles by Joseph Nollekens were carried out to his commission, in expectation of the gallery; the Diana, signed and dated 1778, is now at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Juno, Venus and Minerva, grouped with a Roman antique marble of Paris, are at the J. Paul Getty Museum.[17] Wentworth Woodhouse, with all its contents, subsequently passed to the family of the Marquess's sister, the Earls Fitzwilliam.

Royal visit of 1912

King George V and Queen Mary visited South Yorkshire from 8 to 12 July 1912 and stayed at Wentworth Woodhouse for four days. The house party consisted of a large number of guests, including: Dr Cosmo Gordon Lang, the then-Archbishop of York; the Earl of Harewood and his Countess; the Marchioness of Londonderry; the Marquess of Zetland and Lady Zetland; the Earl of Scarborough and Lady Scarborough; the Earl of Rosse and Lady Rosse; Admiral Lord Charles Beresford and Lady Mina Beresford; Mr Walter Long and Lady Doreen Long; and Lord Helmsley and Lady Helmsley.[18]

The royal visit concluded on the evening of 11 July with a torchlight tattoo by miners, and a musical programme by members of the Sheffield Musical Union and the Wentworth Choral Society. A crowd of 25,000 gathered on the lawn to witness the King and Queen on the balcony of the portico, from which the King gave a speech.[19]

Intelligence connection in the Second World War

During the Second World War, the house served as Training Depot and Headquarters of the Intelligence Corps,[20][21][22] although by 1945 conditions for trainee intelligence soldiers had deteriorated so far that questions were asked in the House of Commons.[23] Some of the training involved motorcycle dispatch rider skills, as Intelligence Corps personnel often used motorcycles. The grounds of the house and surrounding road network were used as motorcycle training areas.[24]

Lease to Lady Mabel College

The Ministry of Health attempted to requisition the house as "housing for homeless industrial families". To prevent this, the 7th Earl attempted to donate the house to the National Trust, but the Trust declined to take it. In the end, Lady Mabel Fitzwilliam, sister of the 7th Earl and a local alderman, brokered a deal whereby the West Riding County Council leased most of the house for an educational establishment, leaving forty rooms as a family apartment.[25] Thus, from 1949 to 1979, the house was home to the Lady Mabel College of Physical Education, which trained female physical education teachers. The college later merged with Sheffield City Polytechnic (now Sheffield Hallam University), which eventually gave up the lease in 1988 as a result of high maintenance costs.[26]

Sheffield City Polytechnic

The period 1979 to 1988 saw students from Sheffield City Polytechnic (now Sheffield Hallam University) based at Wentworth Woodhouse. Two departments, Physical Education and Geography and Environmental Studies, were based on site. The main house housed student accommodation and a dining room and kitchens for lunch and dinner for students living on site. Four separate blocks of modern student accommodation were built in the grounds of the deer park. The Stable Block became the centre of student life, housing offices, lecture rooms, laboratories, squash courts, a swimming pool, and a student bar.

Sale by Fitzwilliam family

By 1989, Wentworth Woodhouse was in a poor state of repair. With the polytechnic no longer a tenant, and with the family no longer requiring the house, the family trustees decided to sell it and the 70 acres (28 ha) surrounding it, but retained the Wentworth Estate's 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) of land. The house was bought by locally born businessman Wensley Grosvenor Haydon-Baillie, who started a programme of restoration, but a business failure saw it repossessed by a Swiss bank and put back on the market in 1998.[27] Clifford Newbold (July 1926 – April 2015),[28] an architect from Highgate, bought it for something over £1.5 million.[29] Newbold progressed with a programme of renovation and restoration, as described in Country Life magazine dated 17 and 24 February 2010.[30] The surrounding parkland is owned by the Wentworth Estates.

In 2014, the house was informally offered for sale by Newbold, with no price specified, but a figure of around £7 million was thought to be sought according to The Times. The house was reported to need works of around £40 million.[31] Following Newbold's death, the house was advertised for sale in May 2015 via Savills with an asking price of £8 million.[32] In February 2016, it was sold to the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust (WWPT) for £7 million after a potential sale to the Hong Kong-based Lake House Group fell through.[33]

On 23 November 2016, in the United Kingdom Chancellor's budget statement of November 2016, it was announced that the Trust was to receive a grant of £7.6 million for restoration work;[34] the Chancellor Philip Hammond noted a claim that the property had been Jane Austen's inspiration for Pemberley in her novel Pride and Prejudice.[35][36] It was thought that there might have been a connection to the house because Austen uses the name Fitzwilliam in her novel, but following the Chancellor's Autumn Statement the Jane Austen Society dismissed the likelihood, given the absence of any evidence that she had visited the estate.[37][32]

Welcoming the grant, Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg dismissed a widely circulated meme claiming that his family benefited from it.[38]

As of 2022, the National Trust was working in partnership with the WWPT to support their ambitions for the site as a visitor attraction; the Trust does not own the property.[39]

Coal mining on the estate

In April 1946, on the orders of Manny Shinwell (the then Labour Party's Minister of Fuel and Power), a "column of lorries and heavy plant machinery" arrived at Wentworth. The objective was the mining of a large part of the estate close to the house for coal. This was an area where the prolific Barnsley seam was within 100 feet (30 m) of the surface and the area in front of the Baroque West wing of the house became the largest open-cast mining site in Britain at that time: 132,000 tons of coal were removed solely from the gardens.[40] Ostensibly the coal was desperately needed in Britain's austere post-war economy to fuel the railways, but the decision has been widely seen as useful cover for an act of class-war spite against the coal-owning aristocracy. A survey by Sheffield University, commissioned by the 8th Earl Fitzwilliam, found the coal to be "very poor stuff" and "not worth the getting"; this contrasted with Shinwell's assertion that it was "exceptionally good-quality."[41]

Minister Shinwell, seemingly intent on the destruction of "the privileged rich", decreed that the mining would continue right up to Wentworth Woodhouse. What followed saw the mining of 99 acres (40 ha) of lawns and woods, the renowned formal gardens and the show-piece pink shale driveway (a by-product of the family's collieries). Ancient trees were uprooted and the debris of earth and rubble was piled 50 ft (15 m) high in front of the family's living quarters.[41]

Local opinion supported the earl. Joe Hall, President of the Yorkshire Area of the National Union of Mineworkers, said that the "miners in this area will go to almost any length rather than see Wentworth Woodhouse destroyed. To many mining communities it is sacred ground". In an industry known for harsh treatment of workers, the Fitzwilliams were respected employers known for treating their employees well. The Yorkshire branch later threatened a strike over the Labour government's plans for Wentworth, and Joe Hall wrote personally to Clement Attlee in a futile attempt to stop the mining.[41] This spontaneous local activism, founded on the genuine popularity of the Fitzwilliam family among locals, was dismissed in Whitehall as "intrigue" sponsored by the earl.[42]

The open-cast mining moved into the fields to the west of the house and continued into the early 1950s. The mined areas took many years to return to a natural state; much of the woodland and the formal gardens were not replaced. The current owners of the property allege that mining operations near the house caused substantial structural damage to the building due to subsidence,[43] and lodged a claim in 2012 of £100 million for remedial works against the Coal Authority.[44] The claim was heard by the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) in April 2016. In its decision dated 4 October 2016 the Tribunal found that the damage claimed for was not caused by mining subsidence.[45]

Two sets of death duties in the 1940s, and the nationalisation of the Fitzwilliam coal mines, greatly reduced the wealth of the family, and most of the contents of the house were dispersed in auction sales in 1948, 1986, and 1998. In the Christies sale of 1948, Rinaldo conquered by Love for Armida by Anthony van Dyck raised 4,600 Guineas[46] (equivalent to £186,849 in 2021).[47] Many items still remain in the family, with many works lent to museums by the "Trustees of the Fitzwilliam Estates".

Architecture

.JPG.webp)

Wentworth Woodhouse comprises two joined houses, forming west and east fronts. The original house, now the west front, with the garden range facing northwest towards the village, was built of brick with stone details. The east front of unsurpassed length is credibly said to have been built[48] as the result of a rivalry with the Stainborough branch of the Wentworth family, which inherited Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford's minor title of Baron Raby, but not his estates (including the notable series of Strafford portraits by Anthony van Dyck and Daniel Mytens), which went to Watson who added Wentworth to his surname. The Stainborough Wentworths, for whom the Strafford earldom was revived, lived at nearby Wentworth Castle, which was purchased in 1708 in a competitive spirit and strenuously rebuilt in a magnificent manner.

Park

Having finished the course of alterations in the hands of John Carr, Lord Fitzwilliam turned in 1790 to the most prominent landscape gardener,[49] Humphry Repton, for whom this was the season's most ambitious project, one that he would describe in detail while the memory was still fresh, in Some Observations of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803). A terrace centred on the main block effected a transition between the house and the rolling grazing land. Four obelisks stood on the bowling green, dwarfed by the scale of the house;[50] Repton re-sited them. Though the parkland had accumulated numerous eye-catchers and features (see below), Repton found there were few trees, the house being surrounded by "coarse grass and boulders"[51] which Repton also removed, before the large-scale earth-moving operations began, effected by men with shovels and donkey-carts, to reshape the lumpy ground into smooth swells. Two large pools, visible from the East Front and the approach drive, were excavated into a serpentine shape. Some of Flitcroft's outbuildings were demolished, though not Carr's handsome stable court (1768), entered through a pedimented Tuscan arch. Many trees were planted.

Follies and garden buildings

The grounds (and surrounding area) contain a number of follies and other garden structures, many with associations in the arena of 18th-century Whig politics. They include:

- Hoober Stand. A tapering pyramid with a hexagonal lantern, named for the ancient wood in which it was erected. It is 98 feet (30 m) high and was built to Flitcroft's design in 1747–48 to commemorate the defeat of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, in which Lord Malton and his surviving son took part; his defensive efforts for the Hanoverian Whig establishment were rewarded with the Lord Lieutenancy of Yorkshire and the title Marquess of Rockingham: thus the monument indirectly reflects the greater glory of the family. The tower, which surveys the surrounding landscape like a watchtower, is open to the public on Sunday afternoons throughout the summer.

- Keppel's Column. A 115 ft (35 m) Tuscan column built to commemorate the acquittal of the court-martialed Admiral Keppel, a close friend of Rockingham. Its entasis visibly bulges owing to an adjustment in its height, made when funding problems reduced the height. It was designed by John Carr.

- The Rockingham Mausoleum. A three-storey building 90 ft (27 m) high, situated in woodland, where only the top level is visible over the treetops. It was commissioned in 1783 by the Earl Fitzwilliam as a memorial to the late first Marquess of Rockingham; it was designed by John Carr, whose first design, for an obelisk, was rejected, in favour of an adaptation of the Roman Cenotaph of the Julii at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, near Arles.[52] The ground floor is an enclosed hall containing a statue of the former prime minister by Joseph Nollekens, plus busts of his eight closest friends. The first floor is an open colonnade with Corinthian columns surrounding the (empty) sarcophagus. The top storey is a Roman-style cupola. Like Hoober Stand, the Mausoleum is open on summer Sunday afternoons.

- Needle's Eye. A 46-foot (14 m) high, sandstone block pyramid with an ornamental urn on the top and a tall Gothic ogee arch through the middle, which straddles a disused roadway. It was built in the 18th century allegedly to win a bet after the second Marquess claimed he could drive a coach and horses through the eye of a needle.

- Bear Pit. Accessible if patronising the nearby Garden centre. Built on two levels with a spiral stair. The outer doorway (about 1630) is part of the architecture of the original house. At the end of the garden is a grotto guarded by two life-sized statues of Roman soldiers.

- Camellia House. The Camellia House, dating mainly from the early 19th century though with late 18th century elements, was built to contain the family's camellia collection.[53] In 2022 plant experts identified a number of rare varieties of the plant, with the oldest dating back to 1792.[54]

"Doric Lodge" in the grounds

"Doric Lodge" in the grounds The Needle's Eye

The Needle's Eye The Rockingham Mausoleum

The Rockingham Mausoleum Doorway to the Bear Pit

Doorway to the Bear Pit Statue

Statue

Listing designations

Many of the structures built by the Rockingham family on and around the Wentworth Woodhouse estate are listed by Historic England. Buildings are listed at one of three grades, I, II* and II, for their architectural and/or historical importance. The house,[55] the stable block[56] and the Rockingham Mausoleum are listed Grade I.[57] Seven structures are listed at Grade II*; the Camellia House,[58] the Needle's Eye,[59] the gateway into the South Court of the house,[60] Keppel's Column,[61] the Hoober Stand[62] and the Ionic[63] and Doric Temples.[64] The park itself is also listed at Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England.[65] Structures listed at Grade II include: the run of lampstands on the east front of the house;[66] the Octagon,[67] North,[68] Mausoleum,[69] Peacock[70] and Doric lodges,[71] together with the gates at the Doric Lodge;[72] a number of farm buildings including a dovecote and a duck house;[73][74][75][76][77][78] water features including two bridges,[79][80] a causeway,[81] a cascade[82] and two fountains in pools;[83][84] three ranges of walls;[85][86][87] the Bear Pit[88] and two adjacent statues of Roman soldiers;[89][90] a garden house,[91] a milestone,[92] a pair of gate piers[93] a Ha-ha[94] and an array of garden statuary including four sets of urns;[95][96][97][98] a pair of vases[99] and the bases of two sundials, the sundials themselves having been removed.[100][101]

Publication

The 2011 BBC series entitled The Country House Revealed was accompanied by a full-length illustrated companion book, published by the BBC, which featured a dedicated chapter on Wentworth Woodhouse (Chapter Four). The six chapters of the book corresponded to the six episodes of the television series.[102]

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in South Yorkshire

- Listed buildings in Wentworth, South Yorkshire

- The Country House Revealed, Wentworth House was featured in Dan Cruickshank's show exploring houses not open to the public and the families that built them.

References

- ↑ Historic England. "Wentworth Woodhouse (1132769)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Historic England. "Wentworth Woodhouse (1001163)". Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ↑ "Wentworth Woodhouse – now open for house tours, garden tours soon". Wentworth Woodhouse. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Visiting Britain's Largest and Smallest Houses by Various Travel Authors on Creators.com – A Syndicate Of Talent".

- ↑ M. J. Charlesworth, "The Wentworths: Family and Political Rivalry in the English Landscape Garden" Garden History 14.2 (Autumn 1986):120–137) passim.

- ↑ Baron Malton, as he then was; he was subsequently created Earl of Malton (1734) and Marquess of Rockingham (1746).

- ↑ The first block constructed already included a ground-floor gallery 130 feet (40 m) long (Charlesworth 1986:126).

- ↑ Ralph Tunnicliffe (c. 1688–1736) appears in several churchwardens' accounts for rebuilding and alterations to churches; just before his involvement at Wentworth Woodhouse, he had been making alterations at Wortley Hall, West Yorkshire, for Edward Wortley Montagu (Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840 3rd ed. [Yale University Press] 1995, s.v. "Tunnicliffe, Ralph"); Wortley Montagu was a prominent Whig politician who moved in the same circles as Lord Malton: an obelisk honouring his wife, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu stands in the rival Wentworth parkland, Wentworth Castle.

- 1 2 Colvin 1995, s.v "Tunnicliffe, Ralph".

- ↑ Quoted in Michael I. Wilson, William Kent, Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685–1748 1984:166f.

- ↑ Pevsner, "The interiors of Wentworth Woodhouse are of a quite exceptional value... The suite along the E front from the Whistlejacket Room at the SE to the library at the NE end is not easily matched anywhere in England" (Yorkshire: The West Riding [Buildings of England] 1967:546).

- ↑ Sir Thomas Robinson in another letter to Carlisle, enclosing Kent's engraved design for the Treasury Buildings in Whitehall,"'tis some satisfaction to me, as a Yorkshireman (and as I was entrusted by Lord Malton in negotiating the agreement between him and Mr. Kent), to reflect that the architect of this beautiful building [the Treasury] is from henceforward to conduct and finish his Lordship's" (quoted in Wilson 1984:166). No intervention by Kent in Flitcroft's project at Wentworth Woodhouse has been detected by historians, however.

- ↑ "as this theatre of politics unfolded over the next half-century it was commemorated by the protagonists in stone, Charlesworth remarked (1986:129).

- ↑ Charlesworth 1986:127.

- ↑ His portraits of William III and George II, commissioned by Rockingham, have not been traced: Martin Hopkinson, "A Portrait by James 'Athenian' Stuart" The Burlington Magazine 132 No. 1052 (November 1990:794–795) p. 794.

- ↑ Dated c. 1768–70 by Ellis K. Waterhouse, "Lord Fitzwilliam's Sporting Pictures by Stubbs" The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 88 No. 521 (August 1946:197, 199).

- ↑ Paul Williamson, "Acquisitions of Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986–1991: Supplement" The Burlington Magazine 133 No. 1065 (December 1991:876–880) p. 879, fig. xi.

- ↑ "Society and Court News". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. 9 July 1912. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ ""My Friends." The King's Speech to His Subjects. Wentworth Spectacle". Sheffield Evening Telegraph. Sheffield. 12 July 1912. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ "British Military History". www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "BBC – WW2 People's War – My War in Two Armies: Part 9 of 10 – Call-up to the British Army". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Bijl, Nick Van Der (2013). Sharing the Secret: The History of the Intelligence Corps 1940–2010. Pen and Sword. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781473833180. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "Intelligence Corps Depot, Rotherham". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 18 December 1945. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "DEAR SERGEANT OR THE STORY OF ROUGH RIDING MOTORCYCLING COURSE | Yorkshire Film Archive". www.yorkshirefilmarchive.com. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Bailey 2007: 397–402.

- ↑ Bailey 2007: 449.

- ↑ Bailey 2007:451.

- ↑ Rotherham Advertiser, 6 May 2015

- ↑ English Country Houses News: Wentworth Woodhouse

- ↑ "Future PLC – Content and Brand Licensing. Stock photos, stock images and image library". www.futurecontenthub.com. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ The Times, 1 November 2014

- 1 2 "Where would Mr Darcy live now? Jane Austen's 'Pemberley' is on sale". The Telegraph. 17 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ "Wentworth Woodhouse sold to conservation group for £7m". BBC News. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Pidd, Helen (24 November 2016). "Why did the chancellor stump up £7.6m for Wentworth Woodhouse?". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ "Wentworth Woodhouse awarded £7.6m in Autumn Statement". BBC News. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Elliott, Larry (23 November 2016). "Autumn statement more Fifty Shades of Grey than Pride and Prejudice". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "'No evidence' Jane Austen ever went to stately home mentioned in autumn statement". The Guardian. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Moorcraft, Bethan (26 April 2017). "Jacob Rees-Mogg meme claiming MP profits from £7.6m Wentworth Woodhouse job deemed 'nonsense'". Bath Chronicle. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ "Visit Wentworth Woodhouse". National Trust. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ↑ Hyams 1971:149.

- 1 2 3 The Sunday Times Magazine, 11 February 2007 p. 23

- ↑ Catherine Bailey, Black Diamonds: The Rise and Fall of an English Dynasty, (London: Penguin) 2007:393. ISBN 0-670-91542-4

- ↑ "Stately home owners claim £100 million as house sinks into ground". The Telegraph. 26 February 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ "£100m Claim for Owners of Wentworth Woodhouse Stately Home". Salmon Assessors Ltd. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber) [2016], decision ref. 0432 (LC)

- ↑ "Vandyck fetches 4,600 Guineas Services". Gloucestershire Echo. 11 June 1948. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ Charlesworth 1986:120–137 passim.

- ↑ The grander term "landscape architect" was a coinage of the late 19th century.

- ↑ Horace Walpole had thought they looked like tenpins.

- ↑ Repton 1803, quoted by Edward Hyams, Capability Brown and Humphrey Repron, 1971:148f.

- ↑ Noted by Charlesworth 1986:135.

- ↑ Historic England. "Camellia House (Grade II*) (1286162)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ↑ Brown, Mark (4 January 2022). "'Quite incredible': some of the world's rarest camellias discovered in Yorkshire". The Guardian.

- ↑ Historic England. "Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade I) (1132769)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Stable Block and Riding School (Grade I) (1203779)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Rockingham Mausoleum including obelisks and railed enclosure (Grade I) (1286386)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Camellia House (Grade II*) (1286162)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Needle's Eye (Grade II*) (1314588)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gateway of South Court, Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade II*) (1193422)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Keppel's Column (Grade II*) (1314632)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Hoober Stand (Grade II*) (1132812)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ionic Temple (Grade II*) (1132730)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Doric Temple (Grade II*) (1193160)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Park and Gardens at Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade II*) (1001163)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Set of six Lamp Standards to east front of Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade II) (1193326)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Octagon Lodge (Grade II) (1192947)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "North Lodge (Grade II) (1132758)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Mausoleum Lodge (Grade II) (1132759)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Peacock Lodge (Grade II) (1286252)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Doric Lodge (Grade II) (1193037)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gates at Doric Lodge (Grade II) (1132761)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "T-shaped range of buildings adjoining stable block (Grade II) (1281512)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Duck House at Home Farm (Grade II) (1314604)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Farm building at Home Farm (Grade II) (1132756)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Farm building with Dovecote at Home Farm (Grade II) (1132757)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Barn at Home Farm (Grade II) (1286402)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Powerhouse adjacent to Home Farm (Grade II) (1314605)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Morley Bridge (Grade II) (1193254)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Bridge and weir at west end of Morley Pond (Grade II) (1132725)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Causeway between Dog Kennel Pond and Morley Pond (Grade II) (1314608)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Cascade (Grade II) (1192814)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Fountain and pool south of Camellia House (Grade II) (1132731)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Fountain and lining to pool in centre of stable block Quadrangle (Grade II) (1240983)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Circular Wall to garden north west of north pavilion of Wentworth Woodhouse (East Front) (Grade II) (1240948)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Perimeter Wall to Wentworth Garden Centre (Grade II) (1132760)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "South Terrace Retaining Wall including parapet and gateway (Grade II) (1286155)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Bear Pit west of Camellia House (Grade II) (1314630)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Statue of Roman Soldier north of Bear Pit (Grade II) (1260764)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Statue of Roman Soldier north of Bear Pit (Grade II) (1203776)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Garden House north of Doric Temple (Grade II) (1314607)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Milestone north west of Mausoleum Lodge (Grade II) (1132810)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Pair of Gate Piers north east of north pavilion of Wentworth Woodhouse (East Front) (Grade II) (1203778)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ha Ha forming northern boundary of the gardens on the west front of Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade II) (1240957)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Group of 6 Garden Urns Flanking Main Steps to Wentworth Woodhouse (West Front) (Grade II) (1132770)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Pair of Cast Iron Urns at south end of Wentworth Woodhouse (West Front) (Grade II) (1132771)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Pair of Cast Iron Urns at north end of Wentworth Woodhouse (West Front) (Grade II) (1286192)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Group of 6 Garden Urns in front of Wentworth Woodhouse (West Front) (Grade II) (1314609)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Pair of Ornamental Vases flanking main avenue to the west front of Wentworth Woodhouse (Grade II) (1203777)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Sundial Base at eastern end of South Terrace (Grade II) (1132772)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Historic England. "Sundial Base at mid point of South Terrace (Grade II) (1193441)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Beckett, Matthew (30 May 2011). "The Country House Revealed – Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire". The Country Seat. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

External links

- Official website

- Rayment, Tim (11 February 2007). "The Mansion of Mystery and Malice – Times Online". The Times. London.

- Wentworth Woodhouse entry from The DiCamillo Companion to British & Irish Country Houses

- Wentworth Village — Wentworth Woodhouse

- "What fate awaits Wentworth Woodhouse?". April 1999.

- Satellite view of Wentworth Woodhouse house and stables