| Zapotec Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

Cocijo God, Lambityeco, Oaxaca | ||

| Name: | Lambityeco Archaeological Site | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | Tlacolula, Oaxaca | |

| Region | Mesoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 16°58′18″N 96°29′31″W / 16.97167°N 96.49194°W | |

| Culture | Zapotec | |

| Language | Zapotec | |

| Chronology | 700 BCE to 750 CE | |

| Period | Mesoamerican Classical - Postclassical | |

| Apogee | 600 - 750 CE | |

| INAH Web Page | Lambityeco Archaeological Site | |

Lambityeco is a small archaeological site about three kilometers west of the city of Tlacolula de Matamoros in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. It is located just off Highway 190 about 25 km (16 mi) east from the city of Oaxaca en route to Mitla. The site has been securely dated to the Late Classical Period.[1]

The Lambityeco name has several possible origins: from zapoteco "Yehui" that translates as Guava River. From "Lambi" corrupted zapoteco of the Spanish word "alambique or still" and of zapoteco "Pityec" that would translate as mound, hence the name would mean "the still mound"

Some claim that Lambityeco is a zapoteco word that means "Hollow Hill" This last interpretation seems to be accepted, considering that this site was a salt producer, as much during prehispanic times as in relatively recent times, since records show that as late as 1940 salt was still produced in this zone.

This process was made by running water through the region dirt, obtaining salt water; this water was boiled in pots to obtain salt after evaporating the water. It is confirmed that this city was a salt production center and that it provided up to 90% of the salt consumed in the valley between 600 and 700 AD. The salt was extracted from dirt in the southern part of the site.

Lambityeco is a small part of the larger site known as Yeguih, which according to another version it is the Zapotec word for "small hill". The two main structures at Lambityeco are Mound 190 and Mound 195. Mound 190 is an elite residence with the entrance flanked by two imposing Cocijo masks, the Zapotec rain god.[2]

The site dates to the Late Classic and Early Postclassic.[3]

Lambityeco was part of a zapoteco settlement from the late classic and early Postclassical period in the Oaxaca valley. The extraordinary artistic quality shown in the various urns, engraved bones and mural paintings in tombs as well as by decorated architectonic elements with mosaics in stucco is remarkable.[3]

Background

The state of Oaxaca is best known for native ancestral cultures. The most numerous and best known are the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, but there are sixteen that are officially recognized. These cultures have survived better to the present than most others in Mexico due to the state's rugged and isolating terrain.

The name of the state comes from the name of its capital city, Oaxaca. This name comes from the Nahuatl word "Huaxyacac",[4] which refers to a tree called a "guaje" (Leucaena leucocephala), found in area around the capital city. The name was originally applied to the Valley of Oaxaca by Nahuatl speaking Aztecs.[5]

Most of what is known about pre-historic Oaxaca comes from archeological work in the Central Valleys region. Evidence of human habitation dating back to about 11,000 years BCE has been found in the Guilá Naquitz cave near the town of Mitla. This area was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2010 in recognition for the "earliest known evidence of domesticated plants in the continent, while corn cob fragments from the same cave are said to be the earliest documented evidence for the domestication of maize." More finds of nomadic peoples date back to about 5000 BCE, with some evidence of the beginning of agriculture. By 2000 BCE, agriculture had been established in the Central Valleys region of the state, with sedentary villages.[6] The diet developed around this time would remain until the Spanish Conquest, consisting primarily of harvested corn, beans, chocolate, tomatoes, chili peppers, squash and gourds. Meat was generally hunted and included tepescuintle, turkey, deer, peccary, armadillo and iguana.[7]

The oldest known major settlements, such as Yanhuitlán and Laguna Zope are located in this area as well. The latter settlement is known for its small figures called "pretty women" or "baby face." Between 1200 and 900 BCE, pottery was being produced in the area as well. This pottery has been linked with similar work done in La Victoria, Guatemala. Other important settlements from the same time period include Tierras Largas, San José Mogote and Guadalupe, whose ceramics show Olmec influence.[6] The major native language family, Oto-Manguean, is thought to have been spoken in northern Oaxaca around 4400 BCE and to have evolved into nine distinct branches by 1500 BCE.[7]

The Zapotecs were the earliest to gain dominance over the Central Valleys region.[7] The first major dominion was centered in Monte Albán, which flourished from 500 BCE until 750 CE.[8]

At its height, Monte Albán was home to some 25,000 people and was the capital city of the Zapotec nation.[7] It remained a secondary center of power for the Zapotecs until the Mixtecs overran it in 1325.[9]

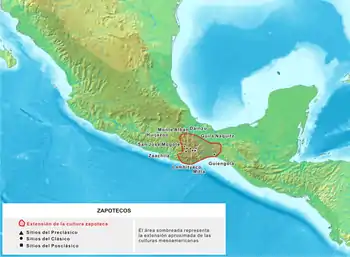

The Zapotecs

The Zapotec civilization was a native ancient culture that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca of southern Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence shows their culture goes back at least 2500 years. They left archaeological evidence at the ancient city of Monte Albán in the form of buildings, ball courts, magnificent tombs and grave goods including finely worked gold jewelry.

Little is known about the Zapotec origins, unlike other mesoamerican cultures, they did not have a known tradition or legend about their origins, they believed that were born directly from rocks, trees and Jaguars.

Archaeologist Marcus Winter points out the following development stages of the culture:[10]

- Agricultural Stage (9500 a 1500 BCE)

- Settlements Stage (1500 a 500 BCE)

- Urban Stage (500 BCE to 750 CE)

- Altépetl or City-State Stage (750 a 1521 CE)

The expansion of the Zapotec empire peaked during the Monte Alban II phase. Zapotecs conquered or colonized settlements far beyond The Valley of Oaxaca. This expansion is visible in several ways; most important is the sudden change of ceramics found in regions outside the valley. These regions previously had their own unique styles which were suddenly replaced with Zapotec style pottery, indicating that they had become part of the Zapotec empire.

Etymology

The name Zapotec is an exonym coming from Nahuatl tzapotēcah (singular tzapotēcatl), which means "inhabitants of the place of sapote". The Zapotec referred to themselves by some variant of the term Be'ena'a, which means "The People."

The site

The site comprises about 197 mounds within a 117 hectares area; most of the mounds are covered by weeds. The site was occupied from 700 BC, and it apogee matches that of Monte Alban. The site was abandoned around 750 AD., and it also matches the Monte Alban abandonment and disintegration of the Zapoteco state. This disintegration formed numerous smaller settlements in the Oaxaca Valley during that time; it is believed that the Lambityeco population might have moved to the Yagul site, located a few kilometers west.

Occupation

Lambityeco occupation began around 700 BC., before the Monte Alban foundation, and concluded around 750 AD. The Lambityeco apogee occurred between 600 and 750 AD.; a time in which significant changes took place in the Oaxaca Valley as a result of the gradual weakening and abandonment of Monte Alban, one of those changes is the blossoming of several ceremonial civic centers. Although of lesser scale and political influence Lambityeco was one of them. These establishments retook political leadership and perhaps most of the Monte Alban population. This site sculpted representations unlike those commonly found in Monte Alban document important royalty marriages, source of the very important postclassical political cohesion. The initial explorations of these palaces, along with their tombs were excavated and recovered in 1961-1976 under the direction of John Paddock.[3]

Structures

Lambityeco is a site with over two hundred platforms of which, unfortunately only two have been explored, structures 195 and 190.[3]

Structure 195

This set includes the largest site structure, it is 6 meters high made up of two slope bodies with stairways on its west side. There are remains of walls of a temple-patio-altar complex. Its rear section was constructed towards the end of the site occupation covers a large area. Under the remains stratified remains of six residences belonging to elite groups and three associated tombs that can be seen climbing up the noted stairway. According to carbon 14 dating those rooms were occupied during an estimated period of 115 years, each house would have been used by a period of 23 to 29 years during four or five generations.[3]

The currently visible construction, once the covering materials were removed, has been called the House of the Great Lord. The building constructed with adobe and stucco finished includes a series of rooms covering a surface of 370 square meters, the north patio rooms surely were used as dormitories, the south Patio is larger and elaborated, it is believed governors attended public matters here. In the east side a two level, three element altar was built, with the characteristic recessed board zapoteco style. The inner tableau has a series of stucco figures summarizing aspects of Lambityeco governors and their spouses.[3]

The people depicted in the tableau are: a man in a horizontal position (face down), with a tipped jaw, has ears, wears a maxtlatl and in his hand holds a human femur. The female is in the same position as the man with a Zapotec hairstyle with entwined ribbons, earrings and round bead necklaces, wears a quechquemitl. In the frieze located on the northern wall, are depicted "Señor 4 cara humana" and "Señora 10 mono" who occupied the oldest Palace between 600 and 625 CE. On the frieze located on the southern wall are depicted "Señor 8 búho" and "Señora 3 turquesa" that utilized the second palace between 625 and 650 CE.[11]

Under the altar frieze is access to Tomb No. 6, on the façade are masks "Señor 1 temblor de tierra" and "Señora 10 caña", the last governors Lambityeco.[11]

Unfortunately the top level has almost disappeared; it would represent "señor 8 muerte" and "señora 5 Caña" that people buried in Tomb 6 located in front of the altar. At the lower level on the left side appears "señor 4 Cara" and "señora 10 Mono", at their right "señora 3 Turquesa" and "señor 8 Búho". They would respectively be the great-grandparents and grandparents of first mentioned couple. Each of the masculine figures of the inferior fraises holds a human femur human in their hands; this was the way to represent the right to govern granted by their ancestors.[3]

Tomb 6 is in front of this altar, where great lords and their wives were buried. The tomb facade also has a recessed tableau with stucco representation of the faces of "señor 1 Terremoto" and "señora 10 Caña", "señor 8 Muerte" parents. The remains of six individuals accompanied by 186 objects were discovered in the tomb, this was frequent in the Oaxaca region, as graves were used several times, placing previous remains to a side (disordered); only the last body remains were in the correct place.[3]

Structure 190

It is located 15 meters south of the previous. Although it is known as Cocijo Patio, in fact it was another high level residence that includes a surface of almost 400 square meters. Rooms are distributed around two patios oriented east-west, in front of each building still is pottery embedded in the dirt floor possibly used for some ceremonies. Between both patios a small room was constructed with east side access to a higher level that allowed construction of a stairway bordered by two walls decorated with recessed boards. Each wall has a large stone and mud mask covered with a thin stucco layer that represents Cocijo, the zapoteco god of rain, thunder and lightning. These identical one meter diameter masks,[11] extraordinary and unique in Zapotec art, allow appreciation of some elements that identify the God as one of the more commonly represented deities and of the most important in the Zapotec pantheon.[3]

The Cocijo image seen in Lambityeco, wears a mask that covers almost all the face; the eyes are framed with a type of goggle; a thick plate in the nose connected to the lower part of the goggles and the mouth mask. Upon the center of the mask in a large feather hairdo and "C glyph"; from the hairdo protrude two tapes adorned in its ends with green stones. The sides have earflaps over a feather base.[3]

The last decorative aspect of this structure is the pectoral, made up of a circular plate superposed to a semi rectangular plate; possibly it represents a shell, jade and obsidian mosaic. An additional and distinctive element is the presence of arms. His right hand holds a vessel from which water or a river flows; the left has a series of rays, hence the name of Thunder or lightning God.[3]

Facing the Cocijo walls, at the end of the Patio is Tomb 2 with masonry walls forming an antechamber and main chamber. The facade was constructed later; it displays a recessed board with double cornices. The remains of seven adult individuals were discovered inside representing at least four generations. In addition to the remains 144 objects were recovered, containing bat claw vessels, thorn decorated braziers, uncooked vessels, carved bones and five identical molded mud urns representing Cocijo.[3]

As per ethnographic data, this would be the supreme priest residence, who controlled and directed all religious topics and at least be the Cocijo terrestrial representative, as is assumed by the urns and masks decorating the central chamber, from where possibly celebrated ceremonies related to the cult to the God of Rain. Generally this priest was related with the Great Lord and has been described as the Lord second son.[3]

Lambityeco images recovered from a tomb

After five months of restoration works, one of the few pictures of prehispanic governors was recovered, located in the facade of Tomb 6 at the Lambityeco archaeological site, in Oaxaca.[12]

These are "señor 1 Temblor" and "señora 10 Caña" with an antiquity of more than 1300 years, recovered by the work of National Anthropology and History Institute (INAH) specialists.[12]

The rescued Lambityeco figures are famous by their realism, as they reveal characteristics of a marriage that is currently preserved by zapotecos women.[12]

References

- ↑ INAH 1973, p.44.

- ↑ Winter 1998, p.108.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Arriola Rivera, María Victoria. "Zona Arqueologica Lambityeco" [Lambityeco Archaeological Site]. INAH (in Spanish). Mexico. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ↑ Consular, Gaceta (October 1996). "Oaxaca". MexConnect. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Nomenclatura" [Nomenclature]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Estado de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- 1 2 "Historia" [History]. ) Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Estado de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Schmal, John P. (2006). "Oaxaca: A Land of Diversity". Houston, TX: Houston Institute for Culture. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ↑ Ardóñez, Maria de Jesús (January 10, 2000). "El territorio del estado de Oaxaca: una revisión histórica" [The territory of the state of Oaxaca: A historical review] (PDF). Investigaciones Geográficas, Boietin del Instituto de Geografia (in Spanish). Mexico: UNAM. 42: 67–86. Archived from the original (pdf) on December 14, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ↑ Akaike, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Winter Marcus, Oaxaca. The archaeological record, Ed. Carteles editores-P.G.O. 2004

- 1 2 3 "Lambityeco" (in Spanish). Oaxaca's Tourist Guide. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Recuperan imágenes que decoran tumba de Lambityeco" [Lambityeco Tomb decorating images are recovered]. Infominuto.com (in Spanish). April 13, 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

Bibliography

- Michael Lind y Javier Urcid The lords of Lambytieco and their nearest neighbors. notas mesoamericanas, número 9, Universidad de las Américas1983

- Marcus, Joyce; Flannery, Kent V. (1996). Zapotec Civilization: How Urban Society Evolved in Mexico's Oaxaca Valley. New aspects of antiquity series. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05078-3. OCLC 34409496.

- Marcus, Joyce; Flannery, Kent V. (2000). "Cultural Evolution in Oaxaca: The Origins of the Zapotec and Mixtec Civilizations". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 358–406. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

- Zeitlin, Robert N. (2000). "Review: Two Perspectives on the Rise of Civilization in Mesoamerica's Oaxaca Valley". Latin American Antiquity. 11 (1): 87–89. JSTOR 1571672.

- Whitecotton, Joseph W. (1990). Zapotec Elite Ethnohistory: Pictorial Genealogies from Eastern Oaxaca. Vanderbilt University publications in anthropology, no. 39. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. ISBN 0-935462-30-9. OCLC 23095346.

- Whitecotton, Joseph W. (1977). The Zapotecs: Princes, Priests and Peasants. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Further reading

External links

- Spencer, Charles S., 2007: State Formation in Ancient Oaxaca, History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies Moscow: KomKniga, ISBN 5-484-01002-0

- Wasserspring, Lois: Oaxacan Ceramics: Traditional Folk Art by Oaxacan Women, ISBN 0-8118-2358-X

- Oaxaca Mio (in Spanish)

- Recuperated images (in Spanish)

- Official site of the State Government (in Spanish)

- Oaxaca's Tourist Guide, on the web since 1995 (in Spanish)

- Oaxaca Photo Blog (in English)

- Oaxaca Travel and Tourism at Curlie

- Mexican and Central American Archaeological Projects – Electronic articles published by the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History

- A political analysis of the Oaxaca Commune

- The Art of Revolution – Read how the people of Oaxaca support their cause by selling art