| Last battle of Bismarck | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Rheinübung | |||||||

Surrounded by shell splashes, Bismarck burns on the horizon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 aircraft carrier 2 battleships 1 battlecruiser 2 heavy cruisers 1 light cruiser 8 destroyers | 1 battleship | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

49 killed 5 wounded 1 destroyer scuttled 1 battleship lightly damaged |

2,200 killed 110 captured 1 battleship scuttled[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||

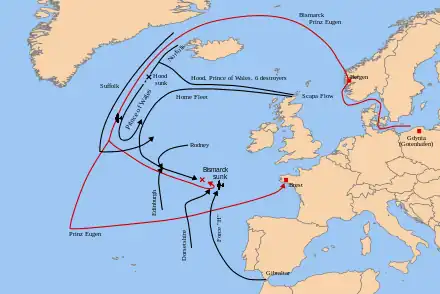

The last battle of the German battleship Bismarck took place in the Atlantic Ocean approximately 300 nautical miles (560 km; 350 mi) west of Brest, France, on 26–27 May 1941 between the German battleship Bismarck and naval and air elements of the British Royal Navy. Although it was a decisive action between capital ships, it has no generally accepted name. It was the culmination of Operation Rheinübung where the attempt of two German ships to disrupt the Atlantic Convoys to the United Kingdom failed with the scuttling of the Bismarck.

The last battle consisted of four main phases. The first phase late on the 26th consisted of air strikes by torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier Ark Royal, which disabled Bismarck's steering gear, jammed her rudders in a turning position and prevented her escape. The second phase was the shadowing and harassment of Bismarck during the night of 26/27 May by British and Polish destroyers, with no serious damage to any ship. The third phase on the morning of 27 May was an attack by the British battleships King George V and Rodney supported by the heavy cruisers Norfolk and Dorsetshire. After about 100 minutes of fighting, Bismarck was sunk by the combined effects of shellfire, torpedo hits and deliberate scuttling.[1] On the British side, Rodney was lightly damaged by near-misses and by the blast effects of her own guns.[2] British warships rescued 110 survivors from Bismarck before being obliged to withdraw because of an apparent U-boat sighting, leaving several hundred men to their fate. A U-boat and a German weathership rescued five more survivors. In the final phase, the withdrawing British ships were attacked the next day on 28 May by aircraft of the Luftwaffe, resulting in the loss of the destroyer HMS Mashona.

Background

Under the command of the Fleet Commander Günther Lütjens, the German battleship Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen tried to break out into the Atlantic in order to attack convoys. The ships were intercepted by a British force from the Home Fleet. In the resulting Battle of the Denmark Strait on 24 May, Bismarck's fuel tanks were damaged and several machinery compartments, including a boiler room, were flooded. Her captain's intention was to reach the port of Brest for repair.[3]

Determined to avenge the sinking of the "Pride of the Navy" HMS Hood in the Battle of the Denmark Strait, the British committed every possible unit to hunting down Bismarck.

- The old Revenge-class battleship HMS Ramillies was detached from convoy duty southeast of Greenland and ordered to set a course to intercept Bismarck if she should attempt to raid the sea lanes off North America.[4]

- The damaged Prince of Wales and the cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk were still in contact with the German ships after the Battle of the Denmark Strait.

- The remainder of the Home Fleet, consisting of the battleship King George V, the battlecruiser Repulse, the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious, four light cruisers and their escorts, had already set sail from Scapa Flow before the loss of the Hood.

- The battleship Rodney was detached from escort duties West of Ireland and set an intercept course for the Bismarck.[5]

- Force H had already left Gibraltar with the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the battlecruiser Renown and the light cruiser Sheffield on 23 May to take over escort duties from other ships, but once it came clear the Bismarck was heading for France, the force set course to intercept Bismarck.[6]

- The heavy cruiser London was escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to the United Kingdom and was also ordered to intercept.[7]

- The light cruiser Edinburgh which was searching for blockade runners in the area West of Cape Finisterre was also ordered to join the hunt.[4]

In the early evening of 24 may Bismarck briefly turned on her pursuers (Prince of Wales and the heavy cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk) to cover the escape of her companion, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen to continue further into the Atlantic. During the late evening of 24 May, an attack was made by a small group of Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers of 825 Naval Air Squadron under the command of Eugene Esmonde from the Victorious. One hit was scored, but caused only superficial damage to Bismarck's armoured belt. Early on 25 May the British forces lost contact with Bismarck, which headed ESE towards France while the British searched northeast, presuming she was returning to Norway. Later on 25 May the commander of the German force, Admiral Günther Lütjens, apparently unaware that he had lost his pursuers, broke radio silence to send a coded message to Germany. This allowed the British to triangulate the approximate position of Bismarck and deduce that the German battleship was heading to France. By now, however, fuel was becoming a major concern to both sides : due to the battle damage, the subsequent loss of fuel and because the Bismarck had not refueled in Norway nor from a tanker whilst underway to the North Atlantic, Lütjens had to maintain economical speed of 21 knots instead of dashing on top speed to France. From the pursuing Home Fleet, Prince of Wales, Repulse, Victorious and the four cruisers had to break off, and the Suffolk as well. Only the King George V and Norfolk were able to continue. Since the destroyer screen of the King George V was also running short on fuel, the Fourth Destroyer Flotilla consisting of the destroyers HMS Cossack, Sikh, Maori and Zulu, and the Polish destroyer ORP Piorun, under command of Captain Philip Vian was ordered to detach from convoy WS-8B and to screen the King George V.[8]

At 10:30 on 26 May Bismarck was detected by a Coastal Command Catalina reconnaissance aircraft from 209 Squadron RAF that had flown over the Atlantic from its base on Lough Erne in Northern Ireland across the Donegal Corridor.[9] It was piloted by British Flying Officer Dennis Briggs[10] and co-piloted by US Navy observer Ensign Leonard B. Smith, USNR.[11] Smith was at the controls when he spotted Bismarck[12] (via a trailing oil slick from the ship's damaged fuel tank) and reported her position to the Admiralty. Shortly before at 09:00 the Ark Royal had launched scouting planes and half an hour after the Catalina, two Swordfish found the Bismarck as well.[13] From then on, the German ship's position was known to the British, although the enemy would have to be slowed significantly if heavy units hoped to engage outside the range of German land-based aircraft. On receiving the message from the Catalina, Vian decided not to join the pursuing British battleships, but to steer directly for the Bismarck.[14] All British hopes were now pinned on Force H and these destroyers.

The battle

_in_1941._(48831444676).jpg.webp)

First phase : The Ark Royal disables the Bismarck

At 14:50 on 26 May in atrocious weather conditions, Ark Royal launched 15 Swordfish for an attack on the Bismarck. The aircraft had not been warned that the Sheffield had been sent forward to shadow the Bismarck, instead they had been told no other ships were in the vicinity. The Swordfish attacked in bad visibility the shadowing cruiser Sheffield, but some of their torpedoes had defective magnetic pistols which caused them to explode on impact on the waves, and the remaining torpedoes could be evaded. At 19:10 the same aircraft were relaunched for a second attack with contact pistol torpedoes.[15] At 19:50 Force H ran into the U-556 which obtained a perfect shooting position to hit both the Ark Royal and Renown but the U-boat had expended all her torpedoes on previous operations and could not attack.[16]

The aircraft made now first contact with the Sheffield at 20:00 which vectored them to the Bismarck. Despite this helping hand and their ASV II radars, they could not find the German ship. Half an hour later they had to recontact the Sheffield which could finally send them to the Bismarck. The attack started at 20:47 and lasted half an hour.[15] Three aircraft had to recontact the Sheffield for a third time.[17] A first hit midships had little effect, but a second hit astern jammed Bismarck's rudder and steering gear 12° to port.[18] This resulted in her being, initially, able to steam only in a large circle.

Bismarck fired her main and secondary armament against the attacking aircraft, trying to hit the low flying torpedo aircraft with the shell splashes. Once the attack was over, Bismarck fired her main battery at the shadowing Sheffield. The first salvo went a mile astray, but the second salvo straddled the cruiser. Shell splinters rained down on Sheffield, killing three men and wounding two others. Four more salvoes were fired but no hits were scored. Sheffield quickly retreated under cover of a smoke screen. Sheffield lost contact with the Bismarck in the low visibility but shortly before 22:00 she met Vian's group of five destroyers and was able to vector them to the Bismarck.[19][20] The King George V and Rodney had joined around 18:00 and were approaching from the northwest. Since Vian's destroyers would keep in touch with the Bismarck and harry her all night, he decided to steer south, even southwest and making a circle in order to be able to engage the Bismarck in the morning silhouetted against the east. The heavy cruiser Norfolk and the light cruiser Edinburgh were also approaching separately from the northwest. Edinburgh had to abandon the chase due to fuel shortage but Norfolk took up a position to the north of Bismarck. Another heavy cruiser Dorsetshire was approaching from the west and would make contact the next morning. After collecting her airplanes Ark Royal and Force H first kept north of Bismarck, but during the night sailed south and remained in the vicinity.[21]

Repair efforts by the crew to free the rudder failed.[22] Bismarck attempted to steer by alternating the power of her three propeller shafts, which, in the prevailing force 8 wind and sea state, resulted in the ship being forced to sail towards King George V and Rodney, two British battleships that had been pursuing Bismarck from the west.[23] At 23:40 on 26 May, Admiral Lütjens delivered to Group West, the German command base, the signal "Ship unmanoeuvrable. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer."[24]

Second phase : Vian's destroyers harass the Bismarck at night

One hour after the Swordfish attack, the Maori and Piorun made contact with the Bismarck at 22:38. Piorun attacked at once, signalling her identity as a Polish ship, but was not able to launch torpedoes. She approached close enough to engage Bismarck with her guns, but then lost contact and played no more role in the battle. Deteriorating weather made a concentrated attack impossible. Throughout that night, Bismarck was the target of intermittent torpedo attacks by Vian's destroyers. In ten approaches between 22:38 and 06:56 the Cossack, Maori, Zulu and Sikh fired sixteen torpedoes but none hit. One of Bismarck's shells sheared off Cossack's antenna and three other shells straddled Zulu wounding three men. Between 02:30 and 03:00 the destroyers fired starshell at Tovey's request in order to make her position visible for the battleships. The constant harrying tactics of the destroyers helped wear down the morale of the Germans and deepened the fatigue of an already exhausted crew.[25][26]

Between 05:00 and 06:00, Lütjens ordered an Arado 196 float plane launched to the French coast, to secure the ship's war diary, footage of the engagement with Hood, and other important documents. Only then was it discovered that the aircraft catapult had been rendered inoperative from battle damage received on the 24th from Prince of Wales. The fully fuelled aircraft was then pushed overboard to reduce the risk of fire in the upcoming battle.[27] Lütjens then radioed at 07:10 for a U-boat to rendezvous with the Bismarck to fetch these documents. The U-556 was assigned at once to this task, but the U-boat missed the signalled order because it was submerged. The U-556 was anyway too low on fuel to be able to carry out the order. The task was then passed on to U-74 but by then the Bismarck had already sunk.[28][29]

Third phase : the Bismarck is lost

As the British units converged on Bismarck's location, Tovey gave his instructions for the final battle. First he ordered the Renown which had closed to within 17 miles of the Bismarck, not to participate in the battle. The Renown was similarly armoured as the Hood and Tovey did not want to risk a repeat.[30] He instructed the commander of Rodney to close to within 15,000 yd (14,000 m) as quickly as possible, and that while he should in general conform to King George V's movements, he was free to manoeuvre independently.[31] The morning of Tuesday 27 May 1941 brought a heavy grey sky, a rising sea and a tearing wind from the northwest. Because of this northwesterly gale, Tovey postponed the final attack from sunrise until clear daylight[32] and concluded an attack on Bismarck from windward was undesirable. He decided to approach on a northwesterly bearing before deploying.[33]

Norfolk was the first ship to sight the Bismarck in the morning of 27 May. In bad visibility the cruiser stumbled upon an unidentified ship, flashing recognition signals before realizing it was the German battleship. Norfolk quickly turned away and made contact with the British battleships before joining the final battle.[32] At 08:43, lookouts on King George V spotted Bismarck, some 25,000 yd (23,000 m) away; Rodney opened fire first at 08:47, followed quickly by King George V. Bismarck was unable to steer due to the torpedo damage to the rudders, and the consequent unpredictable motions made the ship an unstable gun platform and created a difficult gunnery problem. This was further complicated by the gale-force storm.[34] However Bismarck returned fire at 08:50 with her forward guns, and with her second salvo, she straddled Rodney. This was the closest she came to scoring a hit on any British warship in the final engagement,[35] because at 09:02, a 16-inch (406 mm) salvo from Rodney struck the forward superstructure, damaging the bridge and main fire control director and killing most of the senior officers. The salvo also damaged the forward main battery turrets. The aft fire control station took over direction of the aft turrets, but after three salvos was also knocked out. With both fire control stations out of action, Bismarck's shooting became increasingly erratic, allowing the British to close the range. Norfolk and Dorsetshire closed and began firing with their 8 in (203 mm) guns.[36][37] Around 09:10 the Norfolk fired four and the Rodney fired six torpedoes from a distance of more than 10 km, but no hits were observed.[38]

By around 09:31 all of the Bismarck's four main battery turrets were out of action. With the ship no longer able to fight back, First Officer Hans Oels, the senior surviving officer, then issued the order to scuttle the Bismarck – for all damage control measures to cease, for all the watertight doors to be opened, for the engine-room personnel to prepare scuttling charges, and for the crew to abandon ship. Oels moved through the ship, repeating these orders to all he met, until around 10:00 when a shell from King George V penetrated the upper citadel belt and exploded in the ship's after canteen, killing Oels and about a hundred others.[39][40] Gerhard Junack, the senior surviving engineering officer, ordered his men to set the demolition charges with a 9-minute fuse. The engine-room intercom system broke down so he sent a messenger to confirm the order to detonate the charges, but when the messenger never returned Junack primed the charges and ordered the engineering crew to abandon ship.[1]

Once all four of Bismarck's main battery turrets were out of action (by around 09:31,) Rodney closed to around 3,000 yd (2,700 m) with impunity to fire her guns at what was point-blank range into Bismarck's superstructure. King George V remained at a greater distance to increase the possibility that her plunging shells would strike Bismarck's decks vertically and penetrate into the interior. At 10:05 Rodney launched four torpedoes at Bismarck, claiming one hit.[38]

By 10:20 the British battleships were running low on fuel. The Bismarck was settling by the stern due to progressive uncontrolled flooding and had taken on a 20 degree list to port, so Tovey ordered Dorsetshire to close and torpedo the crippled Bismarck while King George V and Rodney disengaged and turned for port. By the time these torpedo attacks took place, Bismarck was already listing so badly that the deck was partly awash. Dorsetshire fired a pair of torpedoes at Bismarck's starboard side, one of which hit. Dorsetshire then moved around to her port side and fired another torpedo, which also hit. Based on subsequent examination of the wreck, the last torpedo appears to have detonated against Bismarck's port side superstructure, which was by then already underwater.[41][42] Bismarck began capsizing at about 10:35, and by 10:40 had slipped beneath the waves, stern first.[43] During the engagement the two British battleships fired some 700 large-caliber shells at Bismarck,[44] and all told, King George V, Rodney, Dorsetshire and Norfolk collectively fired some 2,800 shells, scoring around 400 hits.

Fourth phase: the Luftwaffe retaliates

The Luftwaffe had not been able to intervene on 26 May due to bad weather. Only some reconnaissance flights were made by some Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor which could locate the Rodney. On 27 and 28 May some attempts were made to attack the British ships. In the morning of 27 May one Heinkel He 111 missed the Ark Royal with a few bombs and only four bombers found the British battleships but failed to score a hit.

On 28 May the destroyers Mashona and Tartar were heading for Northern Ireland at economical speed due to their low fuel stocks and were attacked on 28 May in the morning by bombers. At 09:00 the Mashona received a hit, and was abandoned with the loss of 46 crew members. A first attempt to scuttle her with a torpedo from the Tartar failed but then she was sunk by gunfire from other destroyers arriving at the scene.[4][45] The destroyer Maori was also damaged by bombers.[4]

Survivors

_image_03_Bismarck.JPG.webp)

Dorsetshire and Maori picked up 85 and 25 survivors respectively. At 11:40 a lookout on the Dorsetshire thought he spotted a periscope and the rescue effort was abandoned whilst hundreds of Bismarck's survivors were still in the water. While the British cruiser Dorsetshire was busy rescuing survivors from the water, Midshipman Joe Brooks[lower-alpha 2] jumped over the side to help wounded Germans scramble up his ship's side.[47] One German sailor had lost both arms and was hanging onto a rope with his teeth; Brooks tried to save him but failed.[48] Brooks was nearly left behind when the U-boat alarm was given and the Dorsetshire began to pull away while he was still in the water, but he was thrown a line by his shipmates and was pulled aboard.[49] After the battle, the British warships returned to the United Kingdom with 109 Bismarck survivors, as one survivor (Gerhard Lüttich) had died of his wounds the day after his rescue and was buried at sea on 28 May 1941 with full military honours by the crew of HMS Dorsetshire. That evening at 19:30, U-74, picked up three survivors from a dinghy (Herzog, Höntzsch, and Manthey) and the following day at 22:45 the German weather ship Sachsenwald picked up two survivors from a raft (Lorenzen and Maus). The neutral Spanish heavy cruiser Canarias also arrived at the sinking scene but did not find survivors. Out of a crew of over 2,200 men, only 114 survived.[50][51]

Aftermath

After the sinking, Admiral John Tovey said, "The Bismarck had put up a most gallant fight against impossible odds worthy of the old days of the Imperial German Navy, and she went down with her colours flying."

The Board of the Admiralty issued a message of thanks to those involved:

Their Lordships congratulate C.-in-C., Home Fleet, and all concerned in the unrelenting pursuit and successful destruction of the enemy's most powerful warship. The loss of H.M.S. Hood and her company, which is so deeply regretted, has thus been avenged and the Atlantic made more secure for our trade and that of our allies. From the information at present available to Their Lordships there can be no doubt that had it not been for the gallantry, skill, and devotion to duty of the Fleet Air Arm in both Victorious and Ark Royal, our object might not have been achieved.[52]

Unaware of the fate of the ship, Group West, the German command base, continued to issue signals to Bismarck for some hours, until Reuters reported news from Britain that the ship had been sunk. In Britain, the House of Commons was informed of the sinking early that afternoon.[53]

Order of battle

Axis

- German battleship Bismarck

Allied

In the final battle

- The battleships King George V and Rodney.

- The heavy cruisers Norfolk and Dorsetshire.

Made contact before final battle

- 15 swordfish of the aircraft carrier Ark Royal

- The light cruiser Sheffield.

- The destroyers Cossack, Sikh, Zulu, Maori

- The Polish destroyer Piorun

Supporting role

- The aircraft carrier Ark Royal

- The battlecruiser Renown

- The destroyers Mashona, Tartar

See also

- Sink the Bismarck!, a 1960 film based on C. S. Forester's book The Last Nine Days of the Bismarck

- "Sink the Bismarck", a 1960 song by Johnny Horton inspired by the film of the same name.

- Computer Bismarck, a 1980 computer game that simulates the battle.

- Unsinkable Sam, a ship's cat on board Bismarck who allegedly survived the sinking and was adopted by the Royal Navy; probably a tall tale.

Notes

- ↑ Bismarck's complement as Fleet Flagship was 2,220 (2092 + 128 Fleet staff) (Chesenau, p. 224). For Operation Rheinubung she embarked over 100 supernumeraries, including merchant seamen to act as prize crews, cadets in training, and a film unit (Kennedy, p. 33). The number of these supernumeraries, and hence the exact number of casualties, is unknown.

4 floatplanes destroyed - ↑ According to Busch, the British man to jump overboard to help the German survivors was the torpedo officer, Lt II Curver.[46]

References

- 1 2 Gaack & Carr, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 206, 283.

- ↑ Cameron, pp. 6–10.

- 1 2 3 4 Rohwer 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Stephen 1988, p. 83.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, p. 102.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ BBC – WW2 People's War – World War Memories of an Ulster Childhood

- ↑ ""We Shadowed the Bismarck" – In Flg Off. Dennis Briggs' Words | Britain at War". Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ 4 November 2009, Bismarck: British/American Cooperation and the Destruction of the German Battleship Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Naval History and Heritage Command

- ↑ The American Who Helped Sink the Bismarck Defense Media Network 23 November 2021

- ↑ Stephen 1988, p. 88.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 99–100.

- 1 2 Stephen 1988, pp. 88–92.

- ↑ Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 106–109.

- ↑ "Bismarck's· Final· Battle· -· Part· 2". navweaps.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Stephen 1988, pp. 89–92.

- ↑ Stephen 1988, p. 92.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin, p. 235

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 235–236

- ↑ Jackson 2002, p. 91.

- ↑ Stephen 1988, pp. 92–94.

- ↑ Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, pp. 139–142.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, pp. 237–238

- ↑ Busch 1980, p. 125.

- ↑ Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Stephen 1988, p. 94.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1980, p. 210

- 1 2 Müllenheim-Rechberg 1980, p. 158.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 311

- ↑ Bismarck's Final Battle; by William H. Garzke, Jr. and Robert O. Dulin, Jr; Chapter VI; International Naval Research Organization, at

- ↑ Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 288–289

- ↑ Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 290–291

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 239

- 1 2 Stephen 1988, p. 97.

- ↑ Garzke, Jr., William H.; Dulin, Jr., Robert O.; Webb, Thomas G. (1994). "Bismarck's Final Battle". International Naval Research Organization.

- ↑ Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 292–294

- ↑ Jurens et al.

- ↑ Zetterling & Tamelander, p. 281

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1985, p. 246

- ↑ Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 291–294

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 150–152.

- ↑ Busch 1980, p. 148.

- ↑ Ballantyne, Iain (23 May 2016). Bismarck: 24 Hours to Doom. Ipso Books. ISBN 978-1-5040-5915-2. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ↑ McKee, Alexander (1991). Against the Odds: Battles at Sea, 1591–1949. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-025-0. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ↑ "The Bismarck's End". LIFE Magazine. Time Inc. 11 August 1941. p. 35. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ↑ Müllenheim-Rechberg1980, pp. 185–190.

- ↑ Busch 1980, pp. 145–148.

- ↑ "Congratulations to the Fleet". The Times. No. 48938. 29 May 1941. p. 4. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ↑ "WAR SITUATION". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 27 May 1941.

Bibliography

- Bercuson, David J.; Holger, H. Herwig (2001). The Destruction of the Bismarck. Woodstock and New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 1-58567-192-4.

- Brown, J. D. (1968). Carrier Operations in World War II. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0040-7.

- Busch, Fritz-Otto (1980). De vernietiging van de Bismarck (in Dutch). Amsterdam: omega boek BV. ISBN 90-6057-197-5.

- Cameron J., Dulin R., Garzke W., Jurens W., Smith K.,The Wreck of DKM Bismarck A Marine Forensics Analysis

- Carr, Ward (August 2006). "SURVIVING the Bismarck's Sinking". Naval History. 20. ISSN 1042-1920.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All The World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Dewar, A.D. Admiralty report BR 1736: The Chase and Sinking of the "Bismarck". Naval Staff History (Second World War) Battle Summary No. 5, March 1950. Reproduced in facsimile in Grove, Eric (ed.), German Capital Ships and Raiders in World War II. Volume I: From "Graf Spee" to "Bismarck", 1939–1941. Frank Cass Publishers 2002. ISBN 0-7146-5208-3

- Gaack, Malte; Carr, Ward (2011). Schlachtschiff Bismarck—Das wahre Gesicht eines Schiffes—Teil 3 (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: BoD – Books on Demand GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8448-0179-8.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, John (1990). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, John; Jurens, William (2019). Battleship Bismarck: A Design and Operational History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-569-1.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, John; Jurens, William (2019). Battleship Bismarck: A Design and Operational History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press eBook. ISBN 978-1-52675-975-7.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, John (1994). "The Bismarck's Final Battle". Warship International. XXXI (2): 158–190. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Jackson, Robert (2002). The Bismarck. London: Weapons of War. ISBN 978-1-86227-173-9.

- Kennedy, Ludovic. Pursuit: The sinking of the Bismarck. William Collins Sons & Co Ltd 1974. ISBN 0-00-211739-8

- Jerzy Pertek, Wielkie dni małej floty (Great Days of a Small Fleet), Zysk i S-ka, 2011, ISBN 978-83-7785-707-6

- Michael A. Peszke, Poland's Navy 1918-1945, Hippocrene Books, 1999, ISBN 07818-0672-0

- Müllenheim-Rechberg, Burkard von. Battleship Bismarck: A Survivor's Story. Triad/Granada, 1982. ISBN 0-583-13560-9.

- Müllenheim-Rechberg, Burkhard von (1980). De ondergang van de Bismarck (in Dutch). De Boer Maritiem. ISBN 90-228-1836-5.

- Rohwer, J. (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Schofield, B.B. Loss of the Bismarck. Ian Allan, 1972. ISBN 0-7110-0265-7

- Stephen, Martin (1988). Grove, Eric (ed.). Sea Battles in close-up : World War 2. London: Ian Allan ltd. ISBN 0-7110-1596-1.

- Tovey, Sir John C. "Sinking of the German Battleship Bismarck on 27™ May, 1941."

- Zetterling, Niklas; Tamelander, Michael (2009). Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany's Greatest Battleship. Drexel Hill: Casemate.