_-_Dolly_Pentreath_(1685%E2%80%931777)_(The_Last_Speaker_of_Cornish)_-_880806_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

Identifying the last native speaker of the Cornish language was a subject of academic interest in the 18th and 19th centuries, and continues to be a subject of interest today. The traditional view that Dolly Pentreath (1692–1777) was the last native speaker of the language has been challenged by records of other candidates for the last native speaker, and additionally there are records of others who had knowledge of the language at a later date, while not being native speakers.

Finding the last speaker of the language is complicated by the lack of audio recordings or transcriptions owing to the date of the language extinction. It is very difficult to know, without such evidence, whether those reported as speaking Cornish into the 19th century were able to speak the language fluently, or even whether they were speaking it at all. A substratum of Cornish vocabulary persisted in Cornish English, and in some cases those identified as Cornish speakers may have been speaking English with heavy Cornish influence.

Nevertheless the difficulty of identifying the last speaker has not prevented academics spending considerable effort on the topic.

History

It will probably be impossible to establish who the definitive "last native speaker" of Cornish was owing to the lack of extensive research done at the time and the obvious impossibility of finding audio recordings dating from the era. There is also difficulty with what exactly is meant by "last native speaker", as this has been interpreted in differing ways. Some scholars prefer to use terms such as "last monoglot speaker", to refer to a person whose only language was Cornish, "last native speaker", to refer to a person who may have been bilingual in both English and Cornish and furthermore, "last person with traditional knowledge", that is to say someone who had some knowledge of Cornish that had been handed down, but who had not studied the language per se.

The last known monoglot Cornish speaker is believed to have been Chesten Marchant, who died in 1676 at Gwithian. It is not known when she was born. William Scawen, writing in the 1680s, states that Marchant had a "slight" understanding of English and had been married twice.[1]

18th century

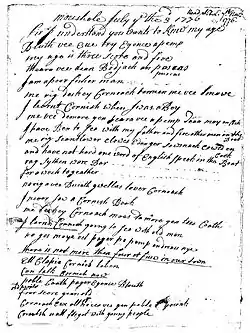

In 1742, Captain Samuel Barrington of the Royal Navy made a voyage to Brittany, taking with him a Cornish sailor of Mount's Bay. He was astonished that this sailor could make himself understood to Breton speakers. In 1768, Barrington's brother, Daines Barrington, searched for speakers of the Cornish language and at Mousehole found Dolly Pentreath, a fish seller of 76 years of age, who "could speak Cornish very fluently". In 1775, he published an account of her in the Society of Antiquaries of London's journal Archaeologia, entitled "On the Expiration of the Cornish Language". He reported that he had also found at Mousehole two other women, some ten or twelve years younger than Pentreath, who could not speak Cornish readily, but who understood it.[2] Pentreath, who died in 1777, is popularly claimed to be the last native speaker of Cornish. Notwithstanding her customary words, "My ny vynnav kewsel Sowsnek!" ("I will not speak English!"), when addressed in that language, she spoke at least some English. After her death, Barrington received a letter, written in Cornish and accompanied by an English translation, from a fisherman in Mousehole named William Bodinar (also spelt Bodinnar and Bodener) stating that he knew of five people who could speak Cornish in that village alone. Barrington also speaks of a John Nancarrow from Marazion who was a native speaker and survived into the 1790s.[3][4] In 1797 a Mousehole fisherman told Richard Polwhele (1760–1838) that William Bodinar "used to talk with her for hours together in Cornish; that their conversation was understood by scarcely any one of the place; that both Dolly and himself could talk in English".[5]

Peter Berresford Ellis poses the question of who was the last speaker of the language, and replies that "We shall never know, for a language does not die suddenly, snuffed out with one last remaining speaker... it lingers on for many years after it has ceased as a form of communication, many people still retaining enough knowledge from their childhood to embark on conversations..." He also notes that in 1777 John Nancarrow of Marazion (Cornish: Marghasyow), not yet forty, could speak the language, and that into the next century some Cornish people "retained a knowledge of the entire Lord's Prayer and Creed in the language".[6] Both William Pryce, in his Archaeologia Cornu-Britannica (1790), and John Whitaker, vicar of Ruan Lanihorne, in his Supplement to Polwhele's History of Cornwall (1799), mention two or three people, known to them, able to speak Cornish. Whitaker tells us that, after advertising money for Cornish, he was referred to a man at St Levan who would be able to give him "as many words of Cornish as I would choose to purchase." Unfortunately he failed to go to St Levan, or to Newlyn where he had been told a woman still lived who spoke Cornish.[7] Polwhele himself mentions in his History of Cornwall, vol. V (1806), an engineer from Truro called Thompson, whom he met in 1789. Thompson was the author of Dolly Pentreath's epitaph and is said to have known far more Cornish than she ever did.[8]

Arthur Boase (1698–1780), who came originally from the parish of Paul, is known as a speaker of Cornish language having taught his children, including the banker and author Henry Boase, the numerals, Lord's Prayer and many phrases and proverbs in that language.[9]

There are two quotes from the 1790s about tin miners from the Falmouth area speaking an unknown language that nobody else understood. In 1793, John Gaze, master's mate to Captain Edward Pellew, on receipt of 80 tin miners from Falmouth for the ship Nymphe, stated "they struck terror wherever they went and seemed like an irruption of barbarians, dressed in the mud-stained smock-frocks and trowsers in which they worked underground, all armed with large clubs and speaking an uncouth jargon (Cornish) which none but themselves could understand." In 1795 James Silk Buckingham, of Flushing, noted "...the arrival one day of a band of three hundred or four hundred tinners ... and speaking an uncouth jargon which none but themselves could understand...". These men were ferried back to Falmouth on the boats that had brought them.[10] The closest area from which such a large number of miners might have come was St Day and Carharrack, but they may have come from the area around Breage. If this "uncouth jargon" was Cornish it would mean that there were still a lot of people using it at the end of the 18th century.[11]

19th century

The Reverend John Bannister stated in 1871 that "The close of the 18th century witnessed the final extinction, as spoken language, of the old Celtic vernacular of Cornwall".[12] However, there is some evidence that Cornish continued, albeit in limited usage by a handful of speakers, through the late 19th century. Matthias Wallis of St Buryan certified to Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte in 1859 that his grandmother, Ann Wallis, née Rowe (c. 1753–1843), had "spoken in my hearing the Cornish Language well. She died about 15 years ago and she was in her 90th year of age. Jane Barnicoate died 2 years ago and she could speak Cornish too."[13][14]

The Rev. Edmund Harvey (born 1828) wrote in his history of Mullion that "I remember as a child myself being taught by tradition, orally of course, to count, and say the Lord's Prayer in Cornish, and I dare say there is many a youngster in Newlyn at the present moment who can score in Cornish as readily as he can in English."[15]

J.M. Doble of Penzance noted in 1878 "Jaky Kelynack remembered, about 70 years ago, that the Breton fishermen and the old Cornishman could converse in their respective languages, and understood one another."[16] Charles Sandoe Gilbert noted in 1817 that a William Matthews of Newlyn, who had died thirty years previously, had been much more fluent than Dolly Pentreath. His son, also called William and died at Newlyn in 1800, was described as being "also well acquainted" with Cornish.[17][18] Letters from West Cornwall, a book written anonymously in 1826, records that "About two years ago when I visited the Land's End, I saw a blind boy who pretended to tell the numbers and a few phrases in Cornish, which he said he had learned from an old woman, since dead."[19]

Barclay Fox recorded in his journal for 23 October 1838:

- Trudged to Penjerrick. Called at Tregedna.

- Mary Louise & Ellen left the room and returned with the most uncouth looking black rascally chimney sweepers I ever saw – old hats, coats breeches & boots, with their faces & hands blacked to the hue of ink. Such a pair as I wouldn't meet in a dark lane for something. They sat on the sofa and conversed in Cornish."[20] Nance recorded that a couple living at Budock in the 1880s were often heard to converse in a strange tongue, which it was thought might have been Cornish.[21]

In 1859 the linguist Edwin Norris reported that an old man had recited for him the Lord's Prayer and part of the Creed which had been taught to him by his father or grandfather.[22]

J. Gwyn Griffiths commented that "there were Cornish immigrants who spoke the language in the leadmine villages of North Cardiganshire, Mid-Wales, in the 1850s".[23] Mary Kelynack, the Madron-born 84-year-old who walked up to London to see the Great Exhibition in 1851 and was presented to the Queen, was believed at the time to have been a Cornish speaker.[24] In 1875 six speakers all in their sixties were discovered in Cornwall.[25] Mrs Catherine Rawlings of Hayle, who died in 1879 at the age of 57, was taught the Lord's prayer and Creed in Cornish whilst at school in Penzance. Rawlings was the mother-in-law of Henry Jenner. John Tremethack, died 1852 at the age of eighty-seven, taught Cornish to his daughter, Frances Kelynack (1799–1895),[26][27] Bernard Victor of Mousehole learned a great deal of Cornish from his father and also his grandfather George Badcock.[8] Victor met Jenner in 1875 and passed on to him his knowledge of Cornish.[28] Victor also taught some Cornish to his granddaughter Louisa Pentreath.[11] The farmer John Davey, who died in 1891 at Boswednack, Zennor, may have been the last person with considerable traditional knowledge of Cornish,[29] such as numbers, rhymes and meanings of place names. Indeed, John Hobson Matthews described him as being able to converse in Cornish on a few simple topics, and gave an example of a rhyme which he had learned from his father.[30] There is good evidence that at least two native speakers outlived John Davey junior: Jacob Care (1798–1892), and John Mann (1833–c 1914).

Jacob Care (christened 4 November 1798 – 1 January 1892) was born in St Ives but later moved to Mevagissey. Frederick McCoskrie, postmaster of Grampound Road, recorded that "He used to speak 'Old Cornish' to me whenever we met, but of it like many other things – no records are kept."

Elizabeth Vingoe (christened 2 December 1804 - buried 11 October 1861), née Hall, of Higher Boswarva, Madron, was able to teach her children, amongst other things, the Lord's Prayer, Ten Commandments and the numerals in Cornish. Vingoe's nephew, Richard Hall (born c. 1861), interviewed her son, William John Vingoe, in 1914. Hall recorded the numerals that he could remember.[11]

Richard Hall himself was probably the most fluent Cornish speaker of the early revival, having learnt it from a young age from members of his family, servants, and Pryce's work, and later from Jenner's Handbook.[11] He is given by A. S. D. Smith as one of only five fluent speakers of revived Cornish before the First World War.[31] Hall recorded that when he was about nine years old they had a maid servant at their home in St Just. The maid, Mary Taskes, noted that he was reading Pryce's Archaeologia Cornu-Britannica and told him that her mother could talk a little of the old language, having been taught by a Mrs Kelynack of Newlyn. He was taken to see the mother and found that she spoke the late Cornish Ten Commandments, Lord's Prayer, and other words as in Pryce.[11]

John Mann, was interviewed in his St Just home by Richard Hall in 1914, Mann then being 80. He told Hall that, as children, he and his friends always conversed in Cornish while at play together. This would have been around 1840–1850. He also said that he had known an old lady, Anne Berryman, née Quick (1766–1858), who talked Cornish. Anne Berryman lived in the house next to the Mann family, with her husband Arthur. After her husband died in 1842 she lived with the Mann family on their farm at Boswednack until her death.[32][33][34] Mann's sisters, Ann and Elizabeth, worked as servants in John Davey's home during the 1850s and 60s.[35] Hall recorded a few words and numerals that Mann could remember.[11]

Martin Uren, born at Wendron in 1813 and also known as Martin Bully, was described by Ralph St Vincent Allin-Collins as a possible traditional Cornish speaker. Living in a cottage on Pennance Lane, Lanner, he was described as speaking a lot of "old gibberish", he died on 5 January 1898. Allin-Collins records what he describes as the Cornish version of the This Little Piggy rhyme from him.[36]

In 1937 the linguist Arthur Rablen recorded that a Mr William Botheras (born 1850) used to go to sea with old fishermen from Newlyn, around the year 1860. These fishermen were in the habit of speaking Cornish while on the boat and held conversations which lasted up to ten to fifteen minutes at a time.[11] A Mr J H Hodge of St Ives remembered his uncle saying that as a boy, in about 1865, he had heard women counting fish in Cornish on the quay there, and also that an old fisherman talked to them in a strange tongue that was understood by them.[37]

However, other traces survived. Fishermen in West Cornwall were counting fish using a rhyme derived from Cornish,[38] and knowledge of the numerals from 1 to 20 was carried through traditionally by many people, well into the 20th century.[11]

Henry Jenner would lead the revival movement in the 20th century. His earliest interest in the Cornish language is mentioned in an article by Robert Morton Nance entitled "Cornish Beginnings",[39]

When Jenner was a small boy at St. Columb, his birthplace, he heard at the table some talk between his father and a guest that made him prick up his ears, and no doubt brought sparkles to his eyes which anyone who told him something will remember. They were speaking of a Cornish language. At the first pause in their talk he put his query... 'But is there really a Cornish Language?' and on being assured that at least there had been one, he said 'Then I'm Cornish—that's mine!'

20th and 21st centuries

The foreman supervising the launching of boats at St Ives in the 1920s would shout Hunchi boree!, which means "Heave away now!", possibly one of the last recorded sentences of traditional Cornish.[40] However, children in some parts of west Cornwall were still using Cornish words and phrases whilst playing games, such as marbles.[41] Many hundreds of Cornish words and even whole phrases ended up in the Anglo-Cornish dialect of the 19th and 20th centuries, many being technical terms in mining, farming and fishing, and the names of flora and fauna.[42]

In the late 20th century, Arnie Weekes, a Canadian-Cornishman, claimed that his mother's family came from an unbroken line of Cornish speakers. It was found on his several visits to Cornwall in the late 1990s that either he or his parents had learned the Unified form of revived Cornish, and therefore any trace of traditional Cornish was lost.[43] In 2007 it was reported by an R. Salmon of New Zealand, on the BBC's Your Voice: Multilingual Nation website, that "Much Cornish was passed down through my family," giving the possibility that other families of Cornish extraction around the world possess traditional knowledge of Cornish.[44]

In 2010 Rhisiart Tal-e-bot disputed the death of Cornish, saying that the grandparents of a student of his had spoken Cornish at home. He said: "It's a myth. There was never a time when the language completely died out, people always had some knowledge of the language although it went quite underground."[45] Likewise, Andrew George MP for St Ives has said in Parliament that "In the early part of the [20th] century, my grandparents on the Lizard were speaking Cornish in a dialect form at home."[46]

References

- ↑ Ellis, P. B. (1974) The Cornish Language. London: Routledge; p. 80

- ↑ Peter Berresford Ellis, The Cornish Language and its Literature, pp. 115–116 online

- ↑ Ellis, P. Berresford, The Story of the Cornish Language (Truro: Tor Mark Press, 1971)

- ↑ Ellis, P. Berresford (1974) The Cornish Language and its Literature. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- ↑ Richard Polwhele, The History of Cornwall, 7 volumes, 1803–1808; vol. 5, pp. 19–20

- ↑ Ellis, Cornish Language, p. 125 online

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p. 81

- 1 2 Michael Everson, Henry Jenner's Handbook of the Cornish Language, 2010

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p. 82

- ↑ A. K. Hamilton Jenkin, Cornwall and its People, 1946 ed., p. 371

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lyon, R. Trevelyan (2001). Cornish, The Struggle for Survival. Taves an Werin.

- ↑ John Bannister, Cornish Place Names (1871)

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 2, 1974, p.174

- ↑ Alan M. Kent, Tim Saunders, Looking at the Mermaid: a Reader in Cornish Literature 900–1900, Francis Boutle, 2000

- ↑ E. G. HARVEY, Mullyon. Truro: Lake, 1875.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p.77

- ↑ Gilbert, Charles Sandoe (1817). An Historical Survey of the County of Cornwall: To which is Added, a Complete Heraldry of the Same, Volume 1. J. Congdon. p. 122.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p.79

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p.80

- ↑ Barclay Fox's Journal. Edited by RL Brett.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p.76

- ↑ Norris, Edwin (1859). The Ancient Cornish Drama. Oxford University Press. p. 466.

- ↑ "Review of The Wheel An anthology of modern poetry in Cornish 1850–1980". Francisboutle.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ Derek R. Williams, Henry and Katharine Jenner, 2004

- ↑ Lach-Szyrma, W. S. (1875) "The Numerals in Old Cornish". In: Academy, London, 20 March 1875 (quoted in Ellis, P. B. (1974) The Cornish Language, p. 127)

- ↑ Peter Berresford Ellis, The Story of the Cornish Language, Tor Mark Press, 1971

- ↑ Paul Parish Registers

- ↑ Peter Berresford Ellis, The Story of the Cornish Language, Tor Mark Press, 1971

- ↑ The Cornish Language and Its Literature: a History, by Peter Berresford Ellis

- ↑ John Hobson Matthews, History of St. Ives, Lelant, Towednack, and Zennor, 1892

- ↑ Independent Study on Cornish Language

- ↑ "Legend of Dolly Pentreath outlived her native tongue". This is Cornwall. 4 August 2011. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ Rod Lyon, Cornish – The Struggle for Survival, 2001

- ↑ UK Census 1851

- ↑ UK Census 1861

- ↑ Allin-Collins, Ralph St. V., "Is Cornish actually dead?", Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 18 (1930): 287—292.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series, Volume VII, Part 1, 1973, p.77

- ↑ Independent Study on Cornish Language

- ↑ page 368, Old Cornwall, Volume V, Number 9 published in 1958.

- ↑ C.Penglase. "History of Cornish | Kernowek or Kernewek | Kernewek, The Cornish Language". Kernowek.com. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ Peter Berresford Ellis, The Cornish Language and its Literature

- ↑ Robert Morton Nance, Celtic Words in Cornish Dialect, Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, 1923 (parts 1, 2 and etymological glossary)

- ↑ The Celtic Languages in Contact, Hildegard L. C. Tristram, 2007

- ↑ Cornish Comments BBC

- ↑ Clare Hutchinson (16 January 2010). "First Cornish-speaking creche is inspired by example set inWales". Wales Online. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ "Cornish Language (Hansard, 23 February 1999)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 23 February 1999. Retrieved 6 April 2017.