László Ede Almásy de Zsadány et Törökszentmiklós | |

|---|---|

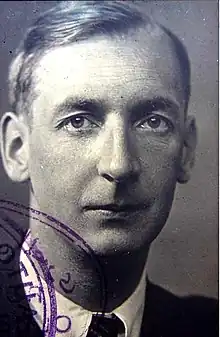

Almásy c. 1945 | |

| Nickname(s) | Abu Ramla (Father of the Sand) |

| Born | 22 August 1895 Borostyánkő, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 22 March 1951 (aged 55) Salzburg, Austria |

| Buried | Salzburg, Austria |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Austro-Hungarian Army Austro-Hungarian Air Force German military intelligence service (Abwehr) Luftwaffe |

| Rank | Hauptmann |

| Unit | 11th Hussars Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops Afrika Korps |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Iron Cross |

László Ede Almásy de Zsadány et Törökszentmiklós (Hungarian: zsadányi és törökszentmiklósi Almásy László Ede; pronounced [ˈɒlmaːʃi ˈlaːsloː ˈɛdɛ]; 22 August/3 November 1895 – 22 March 1951) was a Hungarian aristocrat, motorist, desert explorer, aviator, Scout-leader, and sportsman who served as the basis for the protagonist in both Michael Ondaatje's novel The English Patient (1992) and the movie adaptation of the same name (1996).

Biography

Almásy was born in Borostyánkő, Austria-Hungary (Bernstein im Burgenland, Austria), into a famous Hungarian noble family[1] (his father was zoologist and ethnographer György Almásy), and, from 1911 to 1914, was educated at Berrow School, situated in a private house in Eastbourne, England, where he was tutored by Daniel Wheeler.[2]

World War I

During World War I, Almásy joined the 11th Hussars along with his brother János. Almásy saw action against the Serbs, and then the Russians on the Eastern Front. In 1916, he transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops. After being shot down over Northern Italy in March 1918, Almásy served the remainder of the war as a flight instructor.[3]

Interwar period

After the war, Almásy returned to join the Eastbourne Technical Institute, in East Sussex, England. From November 1921 to June 1922, he lodged at the same address in Eastbourne. He was a member of the pioneering Eastbourne Flying Club.[2]

Returning to Hungary, Almásy became the personal secretary of the Bishop of Szombathely, János Mikes, one of the leading figures of the abortive post-war Habsburg restoration attempt. The young Almásy became involved in these events by accident as the driver of Bishop Mikes when King Karl IV of Hungary returned to Hungary in 1921 to claim the throne, and was helped by Mikes to reach Budapest (from where he was politely but firmly sent back to Austria by Miklós Horthy, the Regent of Hungary). After he was introduced, the King continued to refer to him as Count Almásy, confusing László with another branch of the family. This was the basis for Almásy using the title to his advantage, mostly in Egypt among the Egyptian royalty to open doors that would have remained closed to a commoner. However, he himself admitted in private conversations that the title was not legitimate.[4]

After 1921, Almásy worked as a representative of the Austrian car firm Steyr Automobile in Szombathely, Hungary, and won many car races in the Steyr colours. He managed to persuade a wealthy friend, Prince Antal Eszterházy, to join him in driving a Steyr from Alexandria to Khartoum, before embarking on a hunting expedition to the Dinder River, a feat which had never before been accomplished by an ordinary automobile.[5]

The 1926 drive from Egypt to the Sudan along the Nile proved to be the turning point in his life. Almásy developed an interest in the area and later returned there to drive and hunt. He also demonstrated Steyr vehicles in desert conditions in 1929 with two Steyr lorries and led his first expedition to the desert. In 1931 Almásy made arrangements with a Cairo–Cape Town expedition, led by Captain G. Malins,[6] to make a detour and accompany him to Uweinat and northern Sudan on what was planned to be the first exploration of the Libyan Desert by aeroplane. He was accompanied by Count Nándor Zichy. They took off from Mátyásföld Airport in Budapest on 21 August in a De Havilland Gipsy Moth that had been purchased by Zichy in England a few weeks earlier. Four days later they crashed in a storm near Aleppo. Both survived with scratches only, but the aircraft was a total wreck. The Syrian papers reported them dead, and the Malins expedition left Cairo without them.[7]

.tif.jpg.webp)

Exploring the Libyan Desert

In 1932, Almásy embarked on an expedition to find the legendary Zerzura, "The Oasis of the Birds," with Sir Robert Clayton, Squadron Leader H.W.G.J. Penderel and Patrick Clayton. The expedition used both cars and a De Havilland Gipsy Moth aeroplane owned by Sir Robert Clayton. While Almásy went with two cars to Kufra Oasis, Sir Robert and Penderel discovered a valley with green vegetation inside the Gilf Kebir plateau, which they presumed to be one of the three hidden valleys of Zerzura. Their attempts to reach the mouth of the valley by car failed.[8]

Later in 1932, Almásy's sponsor and travel companion Sir Robert Clayton East-Clayton died of acute spinal poliomyelitis contracted within two months of completing the spring 1932 expedition to the Gilf Kebir. (Not on crash-landing as described in The English Patient but from infection possibly picked up on a desert expedition. However, East-Clayton's wife Dorothy, also a pilot, did die in a peculiar plane accident, at Brooklands on 15 September 1933.)[9]

Despite the setbacks, Almásy succeeded in organizing another Zerzura expedition for the spring of 1933, this time with the desert explorer Prince Kamal el Dine Hussein as his sponsor. He was accompanied by Squadron Leader H.W.G.J. Penderel, the Austrian writer Richard Bermann (pen name Arnold Hollriegel) and the German cinematographer and photographer Hans Casparius. This expedition succeeded in entering the valley discovered the previous year, and circumstantial evidence collected from a Tibou elder at Kufra Oasis confirmed the identity of the valleys as Zerzura. Later on this expedition, Almasy succeeded in entering Wadi Talh, (the third valley of Zerzure), and at the very end of the expedition Almásy, together with Lodovico di Caporiacco, discovered the prehistoric rock paintings of Ain Dua at Jebel Uweinat.[8][10]

In the autumn of 1933 Almásy embarked on a further expedition, this time with the noted German ethnographer Leo Frobenius, his assistant Hans Rhotert and draughtswoman Elisabeth Pauli (later Elisabeth Jensen). They copied and cataloged the known prehistoric rock art sites, and made a large number of new discoveries at Karkur Talh (Jebel Uweinat) and the famous Cave of Swimmers at Wadi Sora in the Gilf Kebir.[8][11]

In the spring of 1934 Almásy led an expedition organised by the Royal Egyptian Automobile Club to the Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uweinat. The expedition erected a memorial tablet for Prince Kelam el Din (who died the previous year, giving another blow to Almásy's ambitions) at the southern tip of the Gilf Kebir plateau. The note left by the expedition now rests in the Heinrich Barth Institut in Köln.[8][12] At Jebel Uweinat Almásy visited the Sudan Defence Force camp commanded by Captain Francis Godfrey Bertram Arkwright, and together they made some new rock art discoveries at the south of Jebel Uweinat. Almásy also visited and copied a panel of paintings found by Captain Arkwright at Jebel Kissu.[13]

In February 1935, Almásy and his colleague Hansjoachim von der Esch became the first Europeans to re-establish contact with the Magyarab tribe, living on an island of the Nile opposite Wadi Halfa in Nubia, who speak Arabic but are believed to be the descendants of Nubian women and Hungarian soldiers serving in the Ottoman army in the 16th century. The accounts of Almásy and von der Esch differ substantially. While Almásy presents the discovery as his own,[7] von der Esch describes the encounter[14] as having been made after Almásy left Wadi Halfa with Count Zsigmond Széchenyi and Jenő Horthy (a relation of Miklós Horthy) on a hunting trip to the Wadi Howar.[15] As Almásy's only illustration shows a group of Egyptian fellahin surrounding a car (no car could have made it over to the island), while von der Esch shows several photos taken on the island, the story of the latter is more likely to be true.

In April 1935, again accompanied by Hansjoachim von der Esch, Almásy explored the Great Sand Sea from Ain Dalla to Siwa Oasis, the last remaining 'blank spot' untouched by earlier explorers or Patrick Clayton's surveys. In his book Almásy claims to have been in the service of the Egyptian government,[7] a statement which led some authors to claim that Almásy was a cartographer of the Libyan Desert in a formal capacity.[16] However, as at the time Patrick Clayton was still the "official" Libyan Desert desert surveyor of the Desert Survey department of the Survey of Egypt, and the two were definitely not on good terms,[17] this claim is very unlikely, with no surviving documentary proof.

In 1939 with the help of Hansjoachim von der Esch, Almásy published a German edition of a compilation (not the entire text) of selected chapters from his books originally published in Hungarian.[18]

End of his stay in Egypt

Almásy never had the means to finance his own expeditions; he was always reliant on financial backers, some of whom raised the suspicion of the British authorities in Egypt. By 1934 both the Italians and the British had suspected him of spying for the other side (though there is no conclusive proof that he did so for either), and in 1935 he was refused permission by the British military authorities to make another expedition to Uweinat.[19] His attention turned to another passion, aviation, and he was deeply involved with setting up gliding activities in Egypt under the auspices of the Royal Egyptian Aviation Club (the president of which, Taher Pasha, was also providing accommodation for Almásy). It is often said (mainly in Hungary) that the Almaza Air Base was named after him, but this has absolutely no foundation; the first airfield of Cairo had carried this name since its establishment during World War I, well before Almásy ever visited Egypt.

World War II

After the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Almásy had to return to Hungary. The British suspected that he was a spy for the Italians, and vice versa. While there is no evidence to suggest that he was involved in any clandestine intelligence gathering prior to the war, he was clearly not welcomed by authorities on either side of the Egypt-Libya border.[20] Hungary formally joined the Axis powers by signing the Tripartite Pact on 20 November 1940.

Nikolaus Ritter of the German military intelligence service, the Abwehr, recruited Almásy in Budapest. As a Hungarian reserve officer, he was permitted to wear the uniform of a Hauptmann (captain/flight lieutenant) of the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe. Initially he worked on maps and country descriptions prepared by the Abteilung IV. Mil.Geo.. Then he was assigned to an Abwehr commando in Libya under the command of Major Nikolaus Ritter, using his aviation and desert experience in various missions. After the failure of Plan el Masri and the first Operation Condor to airdrop two German spies into Egypt (ending with the ditching of one of the two aircraft and the injury of Ritter), Almásy assumed command of the unit.[20][21]

Almásy's greatest achievement during his wartime stay in North Africa was the successful completion of Operation Salam, the infiltration of two German spies through the Libyan Desert behind enemy lines in a manner similar to the Allied Long Range Desert Group. Operation Salam was not a covert operation; Almásy and his team were wearing German uniforms. They used captured British (Canadian-built) Ford cars and trucks with German crosses surreptitiously incorporated into the vehicles' camouflage pattern. Almásy successfully delivered the two Abwehr agents, Johannes Eppler and his radio operator Hans-Gerd Sandstede, to Assiut in Egypt after crossing the Gilf Kebir and Kharga Oasis. Unknown to Almásy and the German command, British code breakers at Bletchley Park had broken the Abwehr hand cypher that Almásy and the spies used for their wireless transmissions. A young intelligence analyst at Bletchley Park, Jean Alington (later Jean Howard), noticed the signal trail. However, as the warning to the British HQ ME in Cairo arrived too late (due to the imminent attack of Rommel), Afrika Korps messages had a higher priority for deciphering and analysis, and Almásy was able to return to his starting point at Gialo unhindered. Eppler and subsequent mission, Operation Condor, was a complete failure; they were both captured within six weeks of reaching Cairo.[21]

Almásy received the Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz) and a promotion to captain for the success of Operation Salam. However, his services in North Africa were no longer needed, and he returned to Hungary, where he wrote a short book on his wartime experiences in Libya.[21][22] There is some evidence that Almásy remained in contact with the Abwehr until late 1943, and yet was involved in the rescue of several Hungarian Jews from the mass deportation to Nazi camps in 1944, including the fencer Yena Fuchs and his family.[21]

Post-war

After the war, as the Communists took over in Hungary, Almásy was arrested for alleged war crimes and treason for joining the armed forces of a foreign power. The charge was based mainly on his wartime book.[22] However, during the trial it emerged that neither the prosecutor nor the judge had read the book, as it was placed on the banned books list by the Soviet occupation forces. Eventually Almásy was acquitted with the help of some influential friends. However, after the trial the Soviet NKVD also started looking for him.

He escaped from the country, supposedly with the aid of the British Intelligence, which reportedly bribed Hungarian Communist officials to enable his release. The bribe was paid by Alaeddin Moukhtar, cousin of King Farouk of Egypt. The British then spirited him into British-occupied Austria using a false passport under the name of Josef Grossman, then on to Rome, where he was escorted by Ronnie Waring, later 18th Duke of Valderano.[23] When Almásy was pursued by a "hit squad" from the Soviet "Committee for State Security" (KGB), Valderano put him on an aeroplane to Cairo.[20]

A note of caution needs to be exercised when taking Valderano's account at face value. While he claimed to have been working for MI6 as the Rome "resident", there is no corroborating proof that Almásy was helped by British Intelligence, and the story was only released following the wide media publicity generated by the 1996 film The English Patient. If indeed Almásy had any contacts with British intelligence during and after the War as rumoured, any evidence is still lying in unreleased intelligence files.[21]

Back in Egypt, Almásy supported himself with odd jobs, some related to aviation, but also leading hunting parties to other parts of Africa. Among his activities was being a dealer in European cars in Cairo. His last brief moment of glory came in December 1950, when King Farouk appointed him Director of the newly founded Egyptian Desert Research Institute.

Scouting

From the beginning he was a member of the Scout movement.[4] In 1921 Almásy became the International Commissioner of the Hungarian Scout Association. With Count Pál Teleki, he took part in organizing the 4th World Scout Jamboree in Gödöllő, Hungary, where Almásy presented the Air Scouts to Robert Baden-Powell on August 9, 1933.

Death

Almásy became ill in 1951 during a visit in Austria, and died 22 March of complications induced by amoebic dysentery—contracted during a trip to Mozambique the previous year—in a hospital in Salzburg, where he was then buried. The epitaph on his grave, erected by Hungarian aviation and desert enthusiasts in 1995, honors him as a Pilot, Saharaforscher und Entdecker der Oase Zarzura (Pilot, Sahara Explorer, and Discoverer of the Zerzura).

The English Patient

Almásy remained a little-known desert explorer until 1996, when he (or rather his fictitious character) was thrown into the limelight by the Academy Award-winning film The English Patient. The screenplay was based on the 1992 novel by Michael Ondaatje. While the storyline is pure fiction, some of the characters and the events surrounding the search for Zerzura and the Cave of Swimmers have been adapted from Geographical Journal articles describing the expeditions of the real Almásy into the Libyan Desert. The publicity attracted by the film helped uncover many hitherto unknown details about Almásy's life, but also resulted in a huge volume of inaccurate or outright untrue claims, mostly related to his World War II activities, which continue to circulate in print and on the web. Many of these inaccuracies and false stories were examined and refuted in a 2013 book on Operation Salam by Kuno Gross, Michael Rolke and András Zboray.[21] In the movie, a native guide is depicted as describing to Almásy the physical location of the cave; "A mountain the shape of a woman's back".[24] The fictionalized Almásy is then depicted as rendering a drawing and some text that he then includes in the book that he keeps for himself.[25]

See also

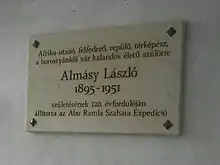

The Abu Ramla Sahara Expedition[26] was established in 2000 with the aim of re-discovering the eastern Sahara region that the legendary Hungarian explorer László Almásy visited, described and discovered during his travels in Egypt, Sudan and Libya. The name of such expedition was inspired by László Almásy himself, who was called by local Saharan tribes: "Abu Ramla" or "Father of the Sand". The Abu Ramla Sahara Expedition visited the Nubian territory and the three ancient capitals of the Kushite kingdom: Kerma, Napata and Meroë. These archaeological sites are registered in UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.

During their campaigns in 2003, 2004 and 2006, they captured various photographic material and filmed those areas where the remains of Kushite royal tombs can still be observed.

On the occasion of the 120th anniversary of the birth of László Almásy (August 2015), the Abu Ramla Sahara Expedition placed a commemorative plaque in Hungarian on main entrance gate of the castle of Bernstein (Borostyánkő), where Almásy was born in 1895.

Filmography

- Rommel Calls Cairo (1959 film)

- Foxhole in Cairo (1960 film)

Notes

- ↑ "Grófok/Counts". ferenczygen.tripod.com.

- 1 2 Eastbourne Local History Society Newsletter Nr 143

- ↑ Bierman, John (2004). The Secret Life of Laszlo Almasy: The Real English Patient. pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 Kubassek, János, A Szahara bűvöletében (Enchanted by the Sahara), Panoráma, Budapest 1999

- ↑ Almásy, László, Autóval Szudánba (With Motorcar to the Sudan), Franklin, Budapest 1929

- ↑ "A NEW YEAR EXPEDITION". Motor Sport Magazine. December 1930. p. 87. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 Almásy, László, Levegőben... homokon... (In Air... on Sand...), Franklin, Budapest 1937

- 1 2 3 4 Almásy, László, Ismeretlen Szahara (Unknown Sahara), Franklin, Budapest 1935

- ↑ "Lady Clayton Killed/An Aeroplane Accident". The Times. 16 September 1933.

- ↑ Hollriegel, ArnoldZarzura, die Oase der kleinen vögel, Orell Füssli, Zürich 1938

- ↑ Rhotert, HansLybische Felsbilder, L. C. Wittich, Darmstadt 1952

- ↑ Monument to Prince Kemal el Din, accessed 20 Oct. 2013

- ↑ Almásy, László, Récentes Explorations dans le Désert Libyque Societé Royale de Geographie de l'Egypte, Cairo, 1936

- ↑ von der Esch, HansjoachimWeenak - die Karawane ruft, Brochhaus, Leipzig 1941

- ↑ Széchenyi, ZsigmondHengergő Homok (Roling Sand), Budapest 1936

- ↑ Török, Zsolt. "László Almásy: The Real 'English patient' - The Hungarian Desert Explorer." Földrajzi Közlemények 121.1-2 (1997): 77-86

- ↑ Clayton, Peter, Desert Explorer (A Biography of Colonel P.A. Clayton), Zerzura Press, Cargreen 1998

- ↑ Almásy, Ladislaus E, Unbekannte Sahara. Mit Flugzeug und Auto in der Libyschen Wüste (The Unknown Sahara. By Aeroplane and Car in the Libyan Desert), Brockhaus, Leipzig 1939

- ↑ Foreign Office corresponcence, National Archives, London, accessed 20 Oct. 2013

- 1 2 3 Kelly, Saul, The Hunt for Zerzura, John Murray, London, 2002

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gross, Kuno, Michael Rolke and András Zboray, Operation Salaam - László Almásy's most daring mission in the Desert War, Belleville, München 2013

- 1 2 Almásy, László, Rommel seregénél Libyában (With Rommel's Army in Libya), Stádium, Budapest 1943

- ↑ Albo d'Oro delle Famiglie Nobili e Notabili Europee, vol XIV, Florence 2000, pp. 811-812

- ↑ "The English Patient Script - transcript from the screenplay and/or Ralph Fiennes, Kristin Scott Thomas, and Juliette Binoche movie". www.script-o-rama.com.

- ↑ The scene that plums are found in the monastery orchard and the scene just before the Cliftons arrive at the base camp on the Crown-owned airplane.

- ↑ "Abu Ramla Sahara Expedition". 28 September 2022.

References

- Almásy, László. Autóval Szudánba (With motorcar to the Sudan). Budapest: Franklin, 1929.

- Almásy, László. Ismeretlen Szahara (Unknown Sahara). Budapest: Franklin, 1935.

- Almásy, L.E. de. Récentes Explorations dans le Désert Lybique. Cairo: Societé Royale de Geographie d'Egypte, 1936.

- German translation by Klaus Kurre in Mythos Zarzura. Belleville, Munich 2020, ISBN 978-3-936298-18-5

- Almásy, László. Levegőben... homokon... (In Air... on Sand...). Budapest: Franklin, 1937.

- Almásy, L.E. Unbekannte Sahara. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1939.

- Almásy, László. Rommel seregénél Libyában (With Rommel's Army in Libya). Budapest: Stádium, 1942.

- Almásy, Ladislaus. Schwimmer in der Wüste (Swimmer of the Desert). Innsbruck: Haymon, 1997. (new edition of Unbekannte Sahara)

- Bermann, Richard (Arnold Hollriegel). Zarzura - die Oase der kleinen vögel. Zürich: Orell Füssli, 1938.

- Bierman, John. The Secret Life of Laszlo Almasy: The Real English Patient. London: Penguin Books, 2004.

- Gross, Kuno, Michael Rolke and András Zboray. Operation Salam - László Almásy's most daring mission in the Desert War. München: Belleville, 2013. ISBN 978-3-943157-34-5 (HC)

- Kelly, Saul. The Hunt for Zerzura. London: John Murray, 2002. ISBN 0-7195-6162-0 (HC)

- Kubassek, János. A Szahara bűvöletében (Enchanted by the Sahara), Panoráma, Budapest 1999 (Biography of Almásy, in Hungarian)

- Ondaatje, Michael. The English Patient. (fiction) 1992.

- Sensenig-Dabbous, Eugene. " 'Will the Real Almásy Please Stand Up!' Transporting Central European Orientalism via The English Patient," in: German Orientalism, Jennifer Jenkins (ed.), Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East Volume 24, No. 2, 2004.

- Széchenyi, Zsigmond. "Hengergő homok" (Rolling sands). Budapest: published by the author, 1936.

- Török, Zsolt: "Salaam Almasy. Almásy László életregénye" (Salaam Almasy: Biography of László Almásy). Budapest: ELTE, 1998.

- Török, Zsolt. "László Almásy: The Real 'English patient' - The Hungarian Desert Explorer." Földrajzi Közlemények 121.1-2 (1997): 77-86.