Lazar Лазар | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Portrait of Prince Lazar in the Monastery of Ravanica (1380s) | |||||

| Prince Martyr Autocrator of all the Serbs | |||||

| Born | c. 1329 Fortress of Prilepac,[1] Kingdom of Serbia | ||||

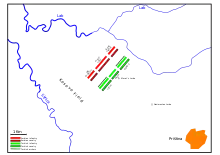

| Died | 15 June 1389 (aged approximately 60) Kosovo Field,[1] District of Branković | ||||

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church | ||||

| Reign | 1373–1389 | ||||

| Successor | Stefan Lazarević | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Milica | ||||

| Issue | Mara Dragana Teodora Jelena Olivera Dobrovoj Stefan Vuk | ||||

| |||||

| Serbian | Лазар Хребељановић | ||||

| Dynasty | Lazarević dynasty | ||||

| Father | Pribac Hrebeljanović | ||||

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox Christian | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Lazar Hrebeljanović (Serbian Cyrillic: Лазар Хребељановић; c. 1329 – 15 June 1389) was a medieval Serbian ruler who created the largest and most powerful state on the territory of the disintegrated Serbian Empire. Lazar's state, referred to by historians as Moravian Serbia, comprised the basins of the Great Morava, West Morava, and South Morava rivers. Lazar ruled Moravian Serbia from 1373 until his death in 1389. He sought to resurrect the Serbian Empire and place himself at its helm, claiming to be the direct successor of the Nemanjić dynasty, which went extinct in 1371 after ruling over Serbia for two centuries. Lazar's programme had the full support of the Serbian Orthodox Church, but the Serbian nobility did not recognize him as their supreme ruler. He is often referred to as Tsar Lazar Hrebeljanović (Serbian: Цар Лазар Хребељановић / Car Lazar Hrebeljanović); however, he only held the title of prince (Serbian: кнез / knez).

Lazar was killed at the Battle of Kosovo in June 1389 while leading a Christian army assembled to confront the invading Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Murad I. The battle ended without a clear victor, with both sides enduring heavy losses. Lazar's widow, Milica, who ruled as regent for their adolescent son Stefan Lazarević, Lazar's successor, accepted Ottoman suzerainty in the summer of 1390.

Lazar is venerated in the Orthodox Christian Church as a martyr and saint, and is highly regarded in Serbian history, culture and tradition. In Serbian epic poetry, he is referred to as Tsar Lazar (Serbian: Цар Лазар / Car Lazar).

Life

Lazar was born around 1329 in the Fortress of Prilepac,[1]13 kilometres (8.1 mi) southeast of Novo Brdo, then an important mining town. His family were the hereditary lords of Prilepac, which together with the nearby Fortress of Prizrenac protected the mines and settlements around Novo Brdo.[2] Lazar's father, Pribac, was a logothete (chancellor) in the court of Stefan Dušan,[3] a member of the Nemanjić dynasty, who ruled as the King of Serbia from 1331 to 1346 and the Serbian Emperor (tsar) from 1346 to 1355. The rank of logothete was relatively modest in the hierarchy of the Serbian court. Dušan became the ruler of Serbia by dethroning his father, King Stefan Uroš III, then rewarding the petty nobles that had supported him in his rebellion, elevating them to higher positions within the feudal hierarchy. Lazar's father was among these nobles and was elevated to the position of logothete by pledging loyalty to Dušan. According to Mavro Orbin, a 16th-century Ragusan historian, Pribac and Lazar's surname was Hrebeljanović. Though Orbin did not provide a source for this claim, it has been widely accepted in historiography.[4]

Courtier

Pribac was awarded by Dušan in yet another way: his son Lazar was granted the position of stavilac at the ruler's court. The stavilac (literally "placer") had a role in the ceremony at the royal table, though he could be entrusted with jobs that had nothing to do with court ritual. The title of stavilac ranked as the last in the hierarchy of the Serbian court. It was, nevertheless, quite prestigious as it enabled its holder to be very close to the ruler. Stavilac Lazar married Milica; according to subsequent genealogies, created in the first half of the 15th century, Milica was the daughter of Prince Vratko, a great-grandson of Vukan. The latter was the son of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja, the founder of the Nemanjić dynasty, which ruled Serbia from 1166 to 1371. Vukan's descendants are not mentioned in any known source that predates the 15th-century genealogies.[4]

Tsar Dušan died suddenly in 1355 at the age of about 47,[5] and was succeeded by his 20-year-old son Stefan Uroš V.[6] Lazar remained a stavilac at the court of the new tsar.[4] Dušan's death was followed by the stirring of separatist activity in the Serbian Empire. Epirus and Thessaly in its southwest broke away by 1359. The same happened with Braničevo and Kučevo, the empire's north-eastern regions controlled by the Rastislalić family, who recognized the suzerainty of King Louis of Hungary. The rest of the Serbian state remained loyal to young Tsar Uroš. Even within it, however, powerful Serbian nobles were asserting more and more independence from the tsar's authority.[7]

Uroš was weak and unable to counteract these separatist tendencies, becoming an inferior power in the state he nominally ruled. He relied on the strongest Serbian noble, Prince Vojislav Vojinović of Zahumlje. Vojislav started as a stavilac at the court of Tsar Dušan, but by 1363 he controlled a large region from Mount Rudnik in central Serbia to Konavle on the Adriatic coast, and from the upper reaches of the Drina River to northern Kosovo.[7] The next in power to Prince Vojislav were the Balšić brothers, Stracimir, Đurađ, and Balša II. By 1363, they gained control over the region of Zeta, which coincided for the most part with present-day Montenegro.[8]

In 1361, Prince Vojislav started a war with the Republic of Ragusa over some territories.[9] Ragusans then asked most eminent persons in Serbia to use their influence to stop these hostilities that were harmful for both sides. In 1362 the Ragusans also applied to stavilac Lazar and presented him with three bolts of cloth. A relatively modest present as it was, it testifies that Lazar was perceived as having some influence at the court of Tsar Uroš. The peace between Prince Vojislav and Ragusa was signed in August 1362. Stavilac Lazar is mentioned as a witness in a July 1363 document by which Tsar Uroš approved an exchange of lands between Prince Vojislav and čelnik Musa. The latter man had been married to Lazar's sister, Dragana, since at least 1355. Musa's title, čelnik ("headman"), was of a higher rank than stavilac.[4]

Minor regional lord

Lazar's activities in the period between 1363 and 1371 are poorly documented in sources.[7] Apparently, he left the court of Tsar Uroš in 1363 or 1365;[3][7] he was about 35 years of age, and had not advanced beyond the rank of stavilac. Prince Vojislav, the strongest regional lord, suddenly died in September 1363. The Mrnjavčević brothers, Vukašin and Jovan Uglješa, became the most powerful nobles in the Serbian Empire. They controlled lands in the south of the Empire, primarily in Macedonia.[7] In 1365, Tsar Uroš crowned Vukašin king, making him his co-ruler. Approximately at the same time, Jovan Uglješa was promoted to the rank of despot.[10] A nephew of Prince Vojislav, Nikola Altomanović, gained control by 1368 of most of the territory of his late uncle; Nikola was about 20 at that time. In this period, Lazar became independent and began his career as a regional lord. It is not clear how his territory developed, but its nucleus was certainly not at his patrimony, the Fortress of Prilepac, which had been taken by Vukašin. The nucleus of Lazar's territory was somewhere in the area bordered by the Mrnjavčevićs in the south, Nikola Altomanović in the west, and the Rastislalićs in the north.[7]

The book Il Regno de gli Slavi [The Realm of the Slavs] by Mavro Orbin, published in Pesaro in 1601, describes events in which Lazar was a main protagonist. Since this account is not corroborated by other sources, some historians doubt its veracity. According to Orbin, Nikola Altomanović and Lazar persuaded Tsar Uroš to join them in their attack on the Mrnjavčević brothers. The clash between the two groups of Serbian lords took place on the Kosovo Field in 1369. Lazar withdrew from the battle soon after it began. His allies fought on, but were defeated by the Mrnjavčevićs. Altomanović barely escaped with his life, while Uroš was captured and briefly imprisoned by the brothers.[3] There are indications that the co-rulers, Tsar Uroš and King Vukašin Mrnjavčević, went their separate ways two years prior to the alleged battle.[7] In 1370 Lazar took from Altomanović the town of Rudnik, a rich mining centre. This could have been a consequence of Altomanović's defeat the year before.[3] In any case, Altomanović could have quickly recovered from this defeat with the help of his powerful protector, the Kingdom of Hungary.[7]

Prince

It is uncertain since when Lazar had borne the title of knez,[7] which is usually translated as "prince".[11] The earliest source that testifies to Lazar's new title is a Ragusan document in Latin, dated 22 April 1371, in which he is referred to as Comes Lazarus.[7][12] Ragusans used comes as a Latin translation of the Slavic title knez.[13] The same document relates that Lazar held Rudnik at that time.[12] In medieval Serbia, knez was not a precisely defined term, and the title had no fixed rank in the feudal hierarchy. Its rank was high in the 12th century, but somewhat lower in the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century. During the reign of Tsar Uroš, when the central authority declined, the high prestige of the title of knez was restored. It was borne by the mightiest regional lord, Vojislav Vojinović, until his death in 1363.[7]

Rise to power

The Ottoman Turks took Gallipoli from Byzantium in 1354. This town at the south-eastern edge of the Balkan Peninsula was the first Ottoman possession in Europe. From there the Ottomans expanded further into the Balkans, and by 1370 they reached Serbian lands, specifically the territory of the Mrnjavčevićs in eastern Macedonia.[14] An army of the Mrnjavčević brothers entered the territory controlled by the Ottomans and clashed with them in the Battle of Marica on 26 September 1371. The Ottomans annihilated the Serbian army; both King Vukašin and Despot Jovan Uglješa were killed in the battle.[15] Vukašin's son and successor, King Marko, became the co-ruler of Tsar Uroš. In December 1371 Uroš died childless, marking the end of the Nemanjić dynasty, which had ruled Serbia for two centuries. The ruler of the Serbian state, which had in fact ceased to exist as a whole, was formally King Marko Mrnjavčević. Powerful Serbian lords, however, did not even consider recognizing him as their supreme ruler.[16] They attacked the Mrnjavčevićs' lands in Macedonia and Kosovo. Prizren and Peć were taken by the Balšić brothers, the lords of Zeta.[17] Prince Lazar took Priština and Novo Brdo, recovering also his patrimony, the Fortress of Prilepac. The Dragaš brothers, Jovan and Konstantin, created their own domain in eastern Macedonia. King Marko was eventually left only a relatively small area in western Macedonia centred on the town of Prilep.[18][19] Jovan Uglješa's widow, Jelena, who became a nun and took the monastic name of Jefimija,[7] lived on with Prince Lazar and his wife Milica.[20]

After the demise of the Mrnjavčević brothers, Nikola Altomanović emerged as the most powerful noble on the territory of the fragmented Serbian state. While Lazar was busy taking Priština and Novo Brdo, Nikola recovered Rudnik from him.[18] By 1372, Prince Lazar and Tvrtko, the Ban of Bosnia, formed an alliance against Nikola. According to Ragusan sources, the Republic of Venice mediated an agreement between Nikola Altomanović and Djuradj Balšić about their joint attack on Ragusa. Nikola was to gain Pelješac and Ston, the Ragusan parts of the region of Zahumlje, which was divided between Nikola's domain, Bosnia, and Ragusa. Louis I, the King of Hungary, sternly warned Nikola and Djuradj to keep off Ragusa,[21] which had been a Hungarian vassal since 1358.[22] By conspiring with Venice, a Hungarian enemy, Nikola lost the protection of Hungary.[23] Lazar, preparing for the confrontation with Nikola, promised King Louis to be his loyal vassal if the king was on his side. Prince Lazar and Ban Tvrtko attacked and defeated Nikola Altomanović in 1373. Nikola was captured in his stronghold, the town of Užice, and given in charge to Lazar's nephews, the Musić brothers, who (according to Orbin with the secret approval of Lazar) blinded him.[24] Lazar accepted the suzerainty of King Louis.[18]

Ban Tvrtko annexed to his state the parts of Zahumlje which were held by Nikola, including the upper reaches of the Drina and Lim Rivers, as well as the districts of Onogošt and Gacko.[25] Prince Lazar and his in-laws, Vuk Branković and čelnik Musa, took most of Nikola's domain. Vuk Branković, who married Lazar's daughter Mara in around 1371, acquired Sjenica and part of Kosovo. Lazar's subordinate, čelnik Musa, governed an area around Mount Kopaonik jointly with his sons Stefan and Lazar, known as the Musić brothers. Djuradj Balšić grabbed Nikola's littoral districts: Dračevica, Konavle, and Trebinje. Ban Tvrtko would take these lands in 1377. In October of that year, Tvrtko was crowned king of the Serbs, Bosnia, Maritime, and Western Areas.[18] Although Tvrtko was a Catholic, his coronation was performed at the Serbian Monastery of Mileševa,[25] or at some other prominent Serbian Orthodox centre in his state. King Tvrtko asserted pretensions to the Serbian throne and the heritage of the Nemanjić dynasty. He was a distant blood relative to the Nemanjićs. Hungary and Ragusa recognized Tvrtko as king, and there are no indications that Prince Lazar had any objections to the new title of his ally Kotromanić. This, on the other hand, does not mean that Lazar recognized Tvrtko as his overlord. King Tvrtko, however, had no support from the Serbian Church, the only cohesive force in the fragmented Serbian state.[18]

Major lord in Serbia

After the demise of Nikola Altomanović, Prince Lazar emerged as the most powerful lord on the territory of the former Serbian Empire.[26] Some local nobles resisted Lazar's authority, but they eventually submitted to the prince. That was the case with Nikola Zojić on Mount Rudnik, and Novak Belocrkvić in the valley of the Toplica River.[27] Lazar's large and rich domain was a refuge for Eastern Orthodox Christian monks who fled from areas threatened by the Islamic Ottomans. This brought fame to Lazar on Mount Athos, the centre of Orthodox monasticism. The Serbian Church (Serbian Patriarchate of Peć) had since 1350 been in schism with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the central authority of the Eastern Orthodox Christianity. A Serb monk from Mount Athos named Isaija, who distinguished himself as a writer and translator, encouraged Lazar to work on the reconciliation of the two patriarchates. Through efforts of Lazar and Isaija, an ecclesiastical delegation was sent to the Constantinopolitan Patriarch to negotiate the reconciliation. The delegation was successful, and in 1375 the Serbian Church was readmitted into communion with the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[18]

The last patriarch of the Serbian Church in schism, Sava IV, died in April 1375.[28] In October of the same year, Prince Lazar and Djuradj Balšić convened a synod of the Serbian Church in Peć. Patriarch Jefrem was selected for the new head of the Church. He was a candidate of Constantinople, or a compromise selection from among the candidates of powerful nobles.[29] Patriarch Jefrem abdicated in 1379 in favour of Spiridon, which is explained by some historians as having resulted from the influence of an undercurrent in the Church associated with Lazar.[30] The prince and Patriarch Spiridon had an excellent cooperation.[29] The Church was obliged to Lazar for his role in ending the schism with Constantinople. Lazar also granted lands to monasteries and built churches.[26] His greatest legacy as a church builder is the Monastery of Ravanica completed in 1381.[31] Some time earlier, he built the Church of St Stephen in his capital, Kruševac; the church would become known as Lazarica. After 1379, he built the Gornjak Monastery in Braničevo. He was one of the founders of the Romanian monasteries in Tismana and Vodiţa. He funded some construction works in two monasteries on Mount Athos, the Serbian Hilandar and the Russian St Panteleimon.[32]

Lazar extended his domain to the Danube in 1379, when the prince took Kučevo and Braničevo, ousting the Hungarian vassal Radič Branković Rastislalić from these regions.[33] King Louis had earlier granted to Lazar the region of Mačva, or at least a part of it, probably when the prince accepted the king's suzerainty.[26] This suggests that Lazar, who was himself a vassal of Louis, had rebelled, and indeed Louis is known to have been organizing a campaign against Serbia in 1378. However, it is not known against whom Louis was intending to act. It is also possible that it was Radič Branković Rastislalić and that Lazar's attack had the approval of Louis.[33]

Lazar's state, known in literature as Moravian Serbia, was larger than the domains of the other lords on the territory of the former Serbian Empire. It also had a better organized government and army. The state comprised the basins of the Great Morava, West Morava, and South Morava Rivers, extending from the source of South Morava northward to the Danube and Sava Rivers. Its north-western border ran along the Drina River. Besides the capital Kruševac, the state included important towns of Niš and Užice, as well as Novo Brdo and Rudnik, the two richest mining centres of medieval Serbia. Of all the Serbian lands, Lazar's state lay furthest from Ottoman centres, and was least exposed to the ravages of Turkish raiding parties. This circumstance attracted immigrants from Turkish-threatened areas, who built new villages and hamlets in previously poorly inhabited and uncultivated areas of Moravian Serbia. There were also spiritual persons among the immigrants, which stimulated the revival of old ecclesiastical centres and the foundation of new ones in Lazar's state. The strategic position of the Morava basins contributed to Lazar's prestige and political influence in the Balkans due to the anticipated Turkish offensives.[26][34]

In charters issued between 1379 and 1388, the prince named himself as Stefan Lazar. "Stefan" was the name borne by all Nemanjić rulers, leading the name to be regarded as a title of Serbian rulers. Tvrtko added "Stefan" to his name when he was crowned king of the Serbs and Bosnia.[29] From a linguistic point of view, Lazar's charters show traits of the Kosovo-Resava dialect of the Serbian language.[35] In the charters, Lazar referred to himself as the autocrator (samodržac in Serbian) of all the Serbian land, or the autocrator of all the Serbs. Autocrator, "self-ruler" in Greek, was an epithet of the Byzantine emperors. The Nemanjić kings adopted it and applied it to themselves in its literal meaning to stress their independence from Byzantium, whose supreme suzerainty they nominally recognized. In the time of Prince Lazar, the Serbian state experienced the loss of some of its lands, the division of the remaining lands among regional lords, the end of the Nemanjić dynasty, and the Turkish attacks. These circumstances raised the question of a continuation of the Serbian state. Lazar's answer to this question could be read in the titles he applied to himself in his charters. Lazar's ideal was the reunification of the Serbian state under him as the direct successor of the Nemanjićs. Lazar had the full support of the Serbian Church for this political programme. However, powerful regional lords—the Balšićs in Zeta, Vuk Branković in Kosovo, King Marko, Konstantin Dragaš, and Radoslav Hlapen in Macedonia—ruled their domains independent from Prince Lazar. Beside that, the three lords in Macedonia became Ottoman vassals after the Battle of Marica. The same happened to Byzantium and Bulgaria.[29] By 1388, Ottoman suzerainty was also accepted by Djuradj Stracimirović Balšić, the lord of Zeta.[25]

A Turkish raiding party, passing unobstructed through territories of Ottoman vassals, broke into Moravian Serbia in 1381. It was routed by Lazar's nobles Crep Vukoslavić and Vitomir in the Battle of Dubravnica, fought near the town of Paraćin.[34] In 1386, the Ottoman Sultan Murad I himself led much larger forces that took Niš from Lazar. It is unclear whether the encounter between the armies of Lazar and Murad at Pločnik, a site southwest of Niš, happened shortly before or after the capture of Niš. Lazar rebuffed Murad at Pločnik.[36] After the death of King Louis I in 1382, a civil war broke out in the Kingdom of Hungary. It seems that Lazar participated in the war as one of the opponents of Prince Sigismund of Luxemburg. Lazar may have sent some troops to fight in the regions of Belgrade and Syrmia. As the Ottoman threat increased and the support for Sigismund grew in Hungary, Lazar made peace with Sigismund, who was crowned Hungarian king in March 1387. The peace was sealed, probably in 1387, with the marriage of Lazar's daughter Teodora to Nicholas II Garay, a powerful Hungarian noble who supported Sigismund.[37] Around the same year, Lazar's daughter Jelena married Djuradj Stracimirović Balšić. About a year before, Lazar's daughter Dragana married Alexander, the son of Ivan Shishman, Tsar of Bulgaria.[26][34]

Battle of Kosovo

Since the encounter at Pločnik in 1386, it was clear to Lazar that a decisive battle with the Ottomans was imminent. After he made peace with Sigismund, to avoid troubles on his northern borders, the prince secured military support from Vuk Branković and King Tvrtko.[34][38] The King of the Serbs and Bosnia was also expecting a bigger Ottoman offensive since his army, commanded by Vlatko Vuković, wiped out a large Turkish raiding party in the Battle of Bileća in 1388.[39] A massive Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad, estimated at between 27,000 and 30,000 men, advanced across the territory of Konstantin Dragaš and arrived in June 1389 on the Kosovo Field near Priština, on the territory of Vuk Branković. The Ottoman army was met by the forces commanded by Prince Lazar, estimated at between 12,000 and 30,000 men, which consisted of the prince's own troops, Vuk Branković's troops, and a contingent under the leadership of Vlatko Vuković sent by King Tvrtko.[34][38] The Battle of Kosovo, the most famous battle in Serbia's medieval history,[39] was fought on 15 June 1389. In the fierce fighting and mutual heavy losses, both Prince Lazar and Sultan Murad lost their lives.[34][38]

Information about the course and the outcome of the Battle of Kosovo is incomplete in the historical sources. It can be concluded that, tactically, the battle was a draw. However, the mutual heavy losses were devastating only for the Serbs, who had brought to Kosovo almost all of their fighting strength.[34][38] Although Serbia under Prince Lazar was an economically prosperous and militarily well organized state, it could not compare to the Ottoman Empire with respect to the size of territory, population, and economic power.[34] Lazar was succeeded by his eldest son Stefan Lazarević. As he was still a minor, Moravian Serbia was administered by Stefan's mother, Milica. She was attacked from the north five months after the battle by troops of the Hungarian King Sigismund. When Turkish forces, moving toward Hungary, reached the borders of Moravian Serbia in the summer of 1390, Milica accepted Ottoman suzerainty. She sent her youngest daughter, Olivera, to join the harem of Sultan Bayezid I. Vuk Branković became an Ottoman vassal in 1392. Now all the Serbian lands were under Ottoman suzerainty, except Zahumlje under King Tvrtko.[38]

Cult

Under Serbian rulers

After the Battle of Kosovo, Prince Lazar was interred in the Church of the Ascension in Priština, the capital of Vuk Branković's domain.[40] After a year or two, in 1390 or 1391, Lazar's relics were transferred to the Ravanica Monastery, which the prince had built and intended as his burial place. The translation was organized by the Serbian Church and Lazar's family.[41] The ceremonial interment of the relics in Ravanica was attended by the highest clergy of the Serbian Church, including Patriarch Danilo III. It is most likely at this time and place that Lazar was canonized, though no account of his canonization was written. He was included among the Christian martyrs, with his feast day being celebrated on 15 June. According to writings by Patriarch Danilo and other contemporary authors, Prince Lazar was captured and beheaded by the Turks. His death could thus be likened to that of early Christian martyrs who were slain by pagans.[40]

In a medieval state with a strong link between the State and the Church, as in Moravian Serbia, a canonization was not only an ecclesiastical act. It also had a social significance. After two centuries of rule of the Nemanjić dynasty, most members of which were canonized, Lazar was the first lay person to be recognized as a saint. During his lifetime, he had achieved considerable prestige as the major lord on the territory of the former Serbian Empire. The Church saw him as the only ruler worthy and capable of succeeding the Nemanjićs and restoring their state.[42] His death was seen as a turning point in Serbian history. The aftermath of the Battle of Kosovo was felt in Serbia almost immediately,[40] although more significant in the long run was the Battle of Marica eighteen years earlier, as the defeat of the Mrnjavčević brothers in it opened up the Balkans to the Turks.[15]

Lazar is celebrated as a saint and martyr in ten cultic writings composed in Serbia between 1389 and 1420;[43] nine of them could be dated closer to the former year than to the latter.[44] These writings were the principal means of spreading the cult of Saint Lazar, and most of them were used in liturgy on his feast day.[45] The Encomium of Prince Lazar by nun Jefimija is considered to have the highest literary quality of the ten texts.[32] Nun Jefimija (whose secular name was Jelena) was a relative of Princess Milica,[44] and the widow of Jovan Uglješa Mrnjavčević. After his death she lived on with Milica and Lazar. Jefimija embroidered her Encomium with a gilded thread on the silken shroud covering Lazar's relics. Stefan Lazarević is regarded as the author of the text carved on a marble pillar that was erected at the site of the Battle of Kosovo.[32] The pillar was destroyed by the Ottomans,[32] but the text is preserved in a 16th-century manuscript.[46] Patriarch Danilo III wrote Narration about Prince Lazar around the time of the translation of Lazar's relics. It is regarded as historically the most informative of the ten writings,[44] though it is a synthesis of hagiography, eulogy, and homily. The prince is celebrated not only as a martyr, but also as a warrior.[47] The patriarch wrote that the Battle of Kosovo ended when both sides became exhausted; both the Serbs and the Turks suffered heavy losses.[48] The central part of Narration is the patriarch's version of Lazar's speech to Serbian warriors before the battle:[49]

You, O comrades and brothers, lords and nobles, soldiers and vojvodas—great and small. You yourselves are witnesses and observers of that great goodness God has given us in this life... But if the sword, if wounds, or if the darkness of death comes to us, we accept it sweetly for Christ and for the godliness of our homeland. It is better to die in battle than to live in shame. Better it is for us to accept death from the sword in battle than to offer our shoulders to the enemy. We have lived a long time for the world; in the end we seek to accept the martyr's struggle and to live forever in heaven. We call ourselves Christian soldiers, martyrs for godliness to be recorded in the Book of Life. We do not spare our bodies in fighting in order that we may accept the holy wreathes from that One who judges all accomplishments. Sufferings beget glory and labours lead to peace.[50]

With Lazar's death, Serbia lost its strongest regional ruler, who might have been seen as the last hope against the expanding Ottomans. This loss could have led to pessimism and a feeling of despair. The authors of the cultic writings interpreted the death of Lazar and the thousands of his warriors on the Kosovo Field as a martyrdom for the Christian faith and for Serbia. Sultan Murad and his army are described as bloodthirsty, godless, heathen beasts. Prince Lazar, by his martyrdom, remains eternally among the Serbs as the good shepherd. His cult was adjoined to the other great cults of medieval Serbia, those of the first canonized Nemanjićs—Saint Simeon (whose secular name was Nemanja) and his son Saint Sava. The cults contributed to the consolidation of the Serbs in a strong religious and political unit.[48] Lazar was, however, in the shadow of Saint Sava and Saint Simeon.[51]

Lazar's son and successor, Stefan Lazarević, was granted the title of despot by the Byzantine Emperor, and he ceased to be an Ottoman vassal in 1402.[52] At least during his reign, the Holy Prince Lazar was probably venerated throughout Moravian Serbia, as well as in two monasteries on Mount Athos, the Serbian Hilandar and the Russian St. Panteleimon, in which the prince had funded some construction works.[32] During Despot Stefan's reign, only one image of Lazar is known to have been painted. It is in a fresco in the Ljubostinja Monastery, built around 1405 by Princess Milica. Lazar is represented there with regal attributes, rather than saintly ones.[51] His next image would not appear until 1594, when it was painted among images of numerous other personages in the Orahovica Monastery in Slavonia (then under Ottoman rule).[53] For his cult, more important than iconography was the cultic literature.[45]

Despot Stefan Lazarević suddenly died in July 1427. He was succeeded by Despot Đurađ, Vuk Branković's son and Lazar's grandson.[54] At the beginning of his reign, Đurađ issued a charter in which he referred to Lazar as a saint. When he reissued the charter in 1445, he avoided the adjective свети "saint", in reference to Lazar, by replacing it with светопочивши "resting in holiness". The avoidance to refer to the prince as a saint can be observed in other documents and inscriptions of that period, including those authored by his daughter Jelena.[55]

During Ottoman rule

The Serbian Despotate fell to the Ottomans in 1459.[56] The veneration of the Holy Prince Lazar was reduced to a local cult, centred on the Ravanica Monastery.[57] Its monks continued to celebrate annually his feast day.[58] The prince had granted 148 villages and various privileges to the monastery. The Ottomans reduced its property to a couple of villages containing 127 households in all, but they exempted Ravanica from some taxes.[59] Italian traveller Marc Antonio Pigafetta, who visited Ravanica in 1568, reported that the monastery was never damaged by the Turks, and the monks practiced freely their religion, except that they were not allowed to ring bells.[60]

Saint Lazar was venerated at the court of Ivan the Terrible, the first Russian tsar (1547–1584),[61] whose maternal grandmother was born in the Serbian noble family of Jakšić.[62] Lazar appears in a fresco in the Cathedral of the Archangel, the burial place of Russian rulers in the Moscow Kremlin. The walls of the cathedral were painted in 1565 with frescoes showing all Russian rulers preceding Ivan the Terrible. Only four non-Russians were depicted: Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos and three Serbs—Saints Simeon, Sava, and Lazar. The prince is also represented in the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, in its nine miniatures depicting the Battle of Kosovo.[61] It is in this Russian book that Prince Lazar was for the first time referred to as a tsar. Around 1700, Count Đorđe Branković would write his Slavo-Serbian Chronicles, in which he claimed that Lazar was crowned tsar. This would influence Serbian folk tradition, in which the prince is to this day known as Tsar Lazar.[63] After the death of Ivan the Terrible, Lazar is rarely mentioned in Russian sources.[61]

Lazar's cult in his Ottoman-held homeland, reduced to the Ravanica Monastery, was given a boost during the office of Serbian Patriarch Paisije. In 1633 and several ensuing years, Lazar was painted in the church of the Patriarchal Monastery of Peć and three other Serbian churches. Patriarch Paisije wrote that Serbian Tsar Dušan adopted Lazar and gave him his relative, Princess Milica, in marriage. In this way, Lazar was the legitimate successor to the Nemanjić dynasty. In 1667, the prince was painted on a wall in the Hilandar Monastery. The same painter created an icon showing Lazar together with Đorđe Kratovac, a goldsmith who was tortured and killed by the Turks and recognized as a martyr. In 1675, Prince Lazar and several Nemanjićs were represented in an icon commissioned by the brothers Gavro and Vukoje Humković, Serbian craftsmen from Sarajevo. The prince's images from this period show him more as a ruler than as a saint, except the icon with Đorđe Kratovac.[64]

After the Great Serb Migration

During the Great Turkish War in the last decades of the 17th century, the Habsburg monarchy took some Serbian lands from the Ottomans. In 1690, a considerable proportion of the Serbian population living in these lands emigrated to the Habsburg Monarchy, as its army retreated from Serbia before the advancing Ottomans. This exodus, known as the Great Serb Migration, was led by Arsenije III Čarnojević, the patriarch of the Serbian Church. The Ravanica monks joined the northward exodus, taking Lazar's relics and the monastery's valuables with them. They settled at the town of Szentendre, near which they built a wooden church and placed the relics in it.[65] They built houses for themselves around the church, and named their new settlement Ravanica. Szentendre also became a temporary see of Patriarch Arsenije III.[66]

The Ravanica monks established contacts with Serbian monasteries in the Habsburg Monarchy, and with the Russian Orthodox Church, from which they received help. They considerably enlarged their library and treasury during their stay at Szentendre. In this period they started to use printing to spread the veneration of the Holy Prince: they made a woodcut representing Lazar as a cephalophore, holding his severed head in his hand.[66] In 1697, the Ravanica monks left their wooden settlement at Szentendre and moved to the dilapidated Monastery of Vrdnik-Ravanica on Mount Fruška Gora in the region of Syrmia. They renovated it and placed Lazar's relics in its church, after which this monastery became the centre of Lazar's cult. It soon came to be more frequently referred to as Ravanica than Vrdnik. By the mid-18th century, a general belief arose that the monastery was founded by Prince Lazar himself.[66] Its church became too small to accommodate all the devotees who assembled there on holidays.[67]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Treaty of Passarowitz, by which Serbia north of the West Morava was ceded from the Ottoman Empire to the Habsburg Monarchy, was signed on 21 July 1718. At that time, only one of the original Ravanica monks who had left their monastery 28 years ago, was still alive. His name was Stefan. Shortly before the treaty was signed, Stefan returned to Ravanica and renovated the monastery, which had been half-ruined and overgrown with vegetation when he came. In 1733, there were only five monks in Ravanica. Serbia was returned to the Ottoman Empire in 1739, but the monastery was not completely abandoned this time.[65]

After the Great Serb Migration, the highest clergy of the Serbian Church actively popularized the cults of canonized Serbian rulers. Arsenije IV Šakabenta, Metropolitan of Karlovci, employed in 1741 the engravers Hristofor Žefarović and Toma Mesmer to create a poster titled "Saint Sava with Serbian Saints of the House of Nemanja", where Lazar was also depicted. Its purpose was not only religious, as it should also remind people of the independent Serbian state before the Ottoman conquest, and of Prince Lazar's fight against the Ottomans. The poster was presented at the Habsburg court. The same engravers produced a book titled Stemmatographia, published in Vienna in 1741. Part of it included copperplates of 29 rulers and saints, among whom were two cephalophores, Jovan Vladimir and Lazar. Stemmatographia was very popular among the Serbs, stirring patriotic feelings in them. The Holy Prince would often be represented as a cephalophore in subsequent works, created in various artistic techniques.[67] An isolated case among the images of Lazar is a 1773 copperplate by Zaharije Orfelin, in which the prince has a parading appearance, without saintly attributes except a halo.[68]

Lazar's relics remained in the Monastery of Vrdnik-Ravanica until 1941. Shortly before Nazi Germany attacked and overran Yugoslavia, the relics were taken to the Bešenovo Monastery, also on Mount Fruška Gora. Syrmia became part of the Nazi puppet state of Croatia, controlled by the fascist Ustaše movement, which conducted large-scale genocide campaigns against the Serbs. The Archimandrite of Vrdnik, Longin, who escaped to Belgrade in 1941, reported that Serbian sacred objects on Fruška Gora were in danger of total destruction. He proposed that they be taken to Belgrade, which was accepted by the Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church. On 14 April 1942, after the German occupation authorities gave their permission, the reliquary with Lazar's relics was transported from Bešenovo to the Belgrade Cathedral Church and ceremonially laid in front of the iconostasis in the church. In 1954, the Synod decided that the relics should be returned the Ravanica Monastery, which was accomplished in 1989—on the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo.[69]

Tradition

Inscription of the curse on the Gazimestan monument"Whoever is a Serb and of Serb birth,

And of Serb blood and heritage,

And comes not to the Battle of Kosovo,

May he never have the progeny his heart desires,

Neither son nor daughter!

May nothing grow that his hand sows,

Neither dark wine nor white wheat!

And let him be cursed from all ages to all ages!"

– Lazar curses those who do not take up arms against the Turks at the Battle of Kosovo, from a poem first published in 1815.[70]

In Serbian epic tradition, Lazar is said to have been visited the night before battle by a grey hawk or falcon from Jerusalem who offered a choice between an earthly kingdom—implying victory at the Battle of Kosovo—or a heavenly kingdom—which would come as the result of a peaceful capitulation or bloody defeat.[71]

- "...the Prophet Elijah then appeared as a gray falcon to Lazar, bearing a letter from the Mother of God that told him the choice was between holding an earthly kingdom and entering the kingdom of heaven..."[72]

According to the epics, Lazar opted for the eternal, heavenly kingdom and consequently perished on the battlefield.[73] "We die with Christ, to live forever", he told his soldiers. That Kosovo's declaration and testament is regarded as a covenant which the Serb people made with God and sealed with the blood of martyrs. Since then all Serbs faithful to that Testament regard themselves as the people of God, Christ's New Testament nation, heavenly Serbia, part of God's New Israel. This is why Serbs sometimes refer to themselves as the people of Heaven.[74]

Jefimija, the former wife of Uglješa Mrnjavčević and later a nun in the Ljubostinja monastery, embroidered the Praise to Prince Lazar, one of the most significant works of medieval Serbian literature.[75] The Serbian Orthodox Church canonised Lazar as Saint Lazar. He is celebrated on June 28 [O.S. June 15] (Vidovdan). Several towns and villages (like Lazarevac), small Serbian Orthodox churches and missions throughout the world are named after him. His alleged remains are kept in Ravanica Monastery.

Titles

It is uncertain since when Lazar had borne the title of knez,[7] which is usually translated as "prince" or "duke".[11] The earliest source that testifies to Lazar's new title is a Ragusan document in Latin, dated 22 April 1371, in which he is referred to as Comes Lazarus.[7][12] Ragusans used comes as a Latin translation of the Slavic title knez.[13] The same document relates that Lazar held Rudnik at that time.[12] In medieval Serbia, knez was not a precisely defined term, and the title had no fixed rank in the feudal hierarchy. Its rank was high in the 12th century, but somewhat lower in the 13th century and the first half of the 14th century. During the reign of Tsar Uroš, when the central authority declined, the high prestige of the title of knez was restored. It was borne by the mightiest regional lord, Vojislav Vojinović, until his death in 1363.[7]

In the period between 1374 and 1379 the Serbian Church recognized Lazar as the "Lord of Serbs and Podunavlje" (господар Срба и Подунавља).[76] In 1381, he is signed as "knez Lazar, of Serbs and Podunavlje" (кнезь Лазарь Срьблѥмь и Подѹнавїю).[77] In an inscription from Ljubostinja dated to 1389, he is mentioned as "knez Lazar, of all Serbs and Podunavlje provinces" (кнезь Лазарь всѣмь Срьблемь и подѹнавскимь странамь господинь).[78] In Hungary, he was known as the "Prince of the Kingdom of Rascia".[79]

In charters issued between 1379 and 1388, he named himself as Stefan Lazar. "Stefan" was the name borne by all Nemanjić rulers, leading the name to be regarded as a title of Serbian rulers. Tvrtko added "Stefan" to his name when he was crowned king of the Serbs and Bosnia.[29] In the charters, Lazar referred to himself as the autocrator (samodržac in Serbian) of "All Serbian Lands" (самодрьжца всеѥ Срьбьскьіѥ землѥ[80]), or the autocrator of "All the Serbs" (самодрьжць вьсѣмь Србьлѥмь). Autocrator, "self-ruler" in Greek, was an epithet of the Byzantine emperors. The Nemanjić kings adopted it and applied it to themselves in its literal meaning to stress their independence from Byzantium, whose supreme suzerainty they nominally recognized.[29]

Issue

Lazar and Milica had at least eight children, five daughters and three sons:

- Mara (died 12 April 1426), married Vuk Branković in around 1371[81]

- Dragana (died before July 1395), married Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Shishman, in around 1386[82][83]

- Teodora (died before 1405), married Hungarian noble Nicholas II Garay in around 1387[84][85]

- Jelena (died March 1443) married firstly Zetan lord Đurađ II Balšić,[86] secondly Bosnian magnate Sandalj Hranić[87]

- Maria Olivera Despina (1372–1444), married Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I in 1390[88]

- Dobrovoj. Died at the birth.

- Stefan (ca. 1377–19 July 1427), prince (1389–1402) and despot (1402–1427)[89]

- Vuk, prince, executed on 6 July 1410[89]

References

- 1 2 3 Byzantinoslavica, Томови 61-62 Предња корица

Academia, 2003;

Serbian Studies, Том 13 Предња корица. North American Society for Serbian Studies, 1999. - ↑ Mihaljčić 1984, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 Fine 1994, p. 374

- 1 2 3 4 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 15–28

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 335

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 345

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 29–52

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 358–59

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p. 43

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 363–64

- 1 2 Fine 1994, p. 624

- 1 2 3 4 Jireček 1911, pp. 435–36

- 1 2 Fine 2006, p. 156

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 377–78

- 1 2 Fine 1994, p. 379

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1975, p. 168

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 382

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 53–77

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 380

- ↑ Jireček 1911, p. 438

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 384

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 341

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1985, p. 57

- ↑ Mihaljčić 1985, p. 58-59

- 1 2 3 Fine 1994, pp. 392–93

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fine 1994, pp. 387–89

- ↑ Šuica 2000, pp. 103–10

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 270

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 78–115

- ↑ Popović 2006, p. 119

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 444

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 175–79

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 1975, pp. 217

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 116–32

- ↑ Stijović 2008, p. 457

- ↑ Reinert 1994, p. 177

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 395–98

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fine 1994, pp. 409–14

- 1 2 Fine 1994, p. 408

- 1 2 3 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 155–58

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 166–67

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 153–54

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 135

- 1 2 3 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 140–43

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 2001, p. 173

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 278

- ↑ Mundal & Wellendorf 2008, p. 90

- 1 2 Emmert 1991, pp. 23–27

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 145

- ↑ Emmert 1991, p. 24

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 2001, p. 184–85

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 500

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 193, 200

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 525–26

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 188–89

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 575

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 193,195

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 204

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 207–10

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 212, 289

- 1 2 3 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 196–97

- ↑ Purković 1996, p. 48

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 96–97

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 200–1

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 214–16

- 1 2 3 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 220–25

- 1 2 Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 226–29

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, p. 230

- ↑ Medaković 2007, p. 75

- ↑ Duijzings 2000, pp. 187–88

- ↑ Macdonald 2002, p. 69

- ↑ "Insight: Legacy of Medieval Serbia". Archaeological Institute of America. October 1999. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Macdonald 2002, p. 70

- ↑ Graubard 1999, p. 27

- ↑ Crnković 1999, p. 221

- ↑ Blagojević 2001, "У периоду између 1374. и 1379. године Српска црква је прихватила кнеза Лазара као „господара Срба и Подунавља".

- ↑ Miklosich 1858, p. 200.

- ↑ Miklosich 1858, p. 215.

- ↑ Jovan Ilić (1995). The Serbian question in the Balkans. Faculty of Geography, University of Belgrade. p. 150. ISBN 9788682657019.

Prince Lazar is for Hungary the "Prince of the Kingdom of Rascia"

- ↑ Miklosich 1858, p. 212.

- ↑ Veselinović & Ljušić 2001, p. 82-85.

- ↑ Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Pavlov 2006.

- ↑ Árvai 2013, p. 106.

- ↑ Fine 1994, pp. 374, 389.

- ↑ Fine 1994, p. 389.

- ↑ Fine 1975, p. 233.

- ↑ Uluçay, M. Çağatay (1985). Padişahların kadınları ve kızları. Türk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 24–5.

- 1 2 Ivić, Aleksa (1928). Родословне таблице српских династија и властеле. Novi sad: Matica Srpska. p. 5.

Sources

- Árvai, Tünde (2013). "A házasságok szerepe a Garaiak hatalmi törekvéseiben [The role of marriages in the Garais' attempts to rise]". In Fedeles, Tamás; Font, Márta; Kiss, Gergely (eds.). Kor-Szak-Határ (in Hungarian). Pécsi Tudományegyetem. pp. 103–118. ISBN 978-963-642-518-0.

- Blagojević, Miloš (2001). Državna uprava u srpskim srednjovekovnim zemljama (in Serbian). Službeni list SRJ. ISBN 9788635504971.

- Blagojević, Miloš. "Teritorije kneza Lazara na Kosovu i Metohiji" (PDF). Zbornik radova s međunarodnog naučnog skupa održanog u Beogradu 16-18 marta 2006. Godine (in Serbian).

- Božić, I.; Đurić, V. J., eds. (1975). О кнезу Лазару, Научни скуп у Крушевцу 1971. Belgrade: Одељење за историју уметности Филозофског факултета у Београду, Народни музеј Крушевац.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Crnković, Gordana P. (1999). "Women Writers in Croatian and Serbian Literatures". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Gender Politics in the Western Balkans: Women and Society in Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Successor States. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01801-1.

- Duijzings, Ger (2000). Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12099-0.

- Emmert, Thomas A. (1991). "The Battle of Kosovo: Early Reports of Victory and Defeat". In Wayne S. Vucinich; Thomas A. Emmert (eds.). Kosovo: Legacy of a Medieval Battle. Minnesota Mediterranean and East European Monographs. Vol. 1. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. ISBN 978-9992287552.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2006). When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans: a study of identity in pre-nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the medieval and early-modern periods. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11414-6.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (December 1975), The Bosnian Church: a new interpretation : a study of the Bosnian Church and its place in state and society from the 13th to the 15th centuries, East European quarterly, ISBN 978-0-914710-03-5, retrieved 12 January 2013

- Graubard, Stephen Richards (1999). A New Europe for the Old?. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1617-5.

- Jireček, Konstantin Josef (1911). Geschichte der Serben (in German). Vol. 1. Gotha, Germany: Friedriech Andreas Perthes A.-G.

- Macdonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim-Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

- Mandić, Svetislav (1986). Velika gospoda sve srpske zemlje i drugi prosopografski prilozi (in Serbian). Srpska književna zadruga. ISBN 9788637900122.

- Medaković, Dejan (2007). Света Гора фрушкогорска (in Serbian). Novi Sad: Prometej. ISBN 978-86-515-0164-0.

- Mihaljčić, Rade (1975). Крај Српског царства (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Mihaljčić, Rade (2001) [1984]. Лазар Хребељановић: историја, култ, предање (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska školska knjiga; Knowledge. ISBN 86-83565-01-7.

- Miklosich, Franz (1858). Monumenta Serbica spectantia historiam Serbiae, Bosnae, Ragusii (in Latin). Vienna: apud Guilelmum Braumüller.

- Mundal, Else; Wellendorf, Jonas (2008). Oral Art Forms and Their Passage Into Writing. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 9788763505048.

- Pavlov, Plamen (2006). Търновските царици. В.Т.:ДАР-РХ.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Popović, Danica (2006). Патријарх Јефрем – један позносредњовековни светитељски култ. Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta (in Serbian). Belgrade: Vizantološki institut, SANU. 43. ISSN 0584-9888.

- Purković, Miodrag Al. (1959), Srpski vladari (in Serbian)

- Purković, Miodrag Al. (1996). Кћери кнеза Лазара: историјска студија (in Serbian). Belgrade: Pešić i sinovi.

- Reinert, Stephen W (1994). "From Niš to Kosovo Polje: Reflections on Murād I's Final Years". In Zachariadou, Elizabeth (ed.). The Ottoman Emirate (1300–1389). Heraklion: Crete University Press. ISBN 978-960-7309-58-7.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Stijović, Rada (2008), Неке особине народног језика у повељама кнеза Лазара и деспота Стефана, Južnoslovenski Filolog (in Serbian), Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 64, ISSN 0350-185X

- Šuica, Marko (2000). Немирно доба српског средњег века: властела српских обласних господара (in Serbian). Belgrade: Službeni list SRJ. ISBN 86-355-0452-6.

- Trifunović, Đorđe (1989). "Житије и владавина светог кнеза Лазара, приредио Ђорђе Трифуновић". Крушевац: Багдала.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Veselinović, Andrija; Ljušić, Radoš (2001). Српске династије. Нови Сад: Плантонеум. ISBN 978-86-83639-01-4.