The Earl Beauchamp | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Commissioner of Works | |

| In office 3 November 1910 – 6 August 1914 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | Lewis Vernon Harcourt |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Emmott |

| Lord President of the Council | |

| In office 16 June 1910 – 3 November 1910 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Wolverhampton |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Morley of Blackburn |

| In office 5 August 1914 – 25 May 1915 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Morley of Blackburn |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Crewe |

| Lord Steward of the Household | |

| In office 31 July 1907 – 16 June 1910 | |

| Monarchs | Edward VII George V |

| Prime Minister | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman H. H. Asquith |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Liverpool |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Chesterfield |

| Captain of the Gentlemen-at-Arms | |

| In office 18 December 1905 – 31 July 1907 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Prime Minister | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Preceded by | The Lord Belper |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Denman |

| 20th Governor of New South Wales | |

| In office 18 May 1899 – 30 April 1901 | |

| Monarchs | Queen Victoria Edward VII |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Hampden |

| Succeeded by | Harry Rawson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 February 1872 |

| Died | 14 November 1938 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Lady Lettice Grosvenor (1876–1936) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

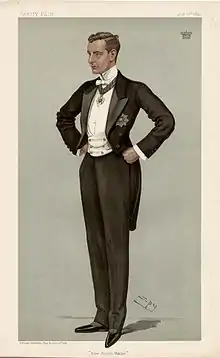

William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp, KG, KCMG, CB, KStJ, PC (20 February 1872 – 14 November 1938), styled Viscount Elmley until 1891, was a British Liberal politician. He was Governor of New South Wales between 1899 and 1901, a member of the Liberal administrations of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H. Asquith between 1905 and 1915, and leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords between 1924 and 1931. When political enemies threatened to make his homosexuality public, he resigned from office to go into exile. Lord Beauchamp is often assumed to be the model for the character Lord Marchmain in Evelyn Waugh's novel Brideshead Revisited.

Background and education

Beauchamp was the eldest son of Frederick Lygon, 6th Earl Beauchamp, by his first wife, Lady Mary Catherine, daughter of Philip Stanhope, 5th Earl Stanhope. He was educated at Eton College and Christ Church, University of Oxford, where he showed an interest in evangelism, joining the Christian Social Union.[1][2] Beauchamp's mentors included the Eton master Henry Luxmoore, who encouraged his pupils to "strive after what was best in all things", and Anglican minister the Rev. James Adderley, who believed in practical Christianity, and devoted his life to philanthropy in London's East End.[3]

Early career

Beauchamp succeeded his father in the earldom in 1891 at the age of 18, and was mayor of Worcester between 1895 and 1896. A progressive in his ideas, he was surprised to be offered the post of Governor of New South Wales in May 1899. Though he was good at the job and enjoyed the company of local artists and writers, he was unpopular in the colony for a series of gaffes and misunderstandings, most notably over his reference to the "birthstain" of Australia's convict origins.[1] His open association with the high church and Anglo-Catholicism caused increased perturbation in the Evangelical Council.[1]

In Sydney, William Carr Smith, rector of St James' Church was his chaplain.[4] Beauchamp returned to Britain in 1900, saying that his duties had failed to stimulate him.

Political career

In 1902, Beauchamp joined the Liberal Party and the same year he married Lady Lettice Mary Elizabeth Grosvenor, the daughter of Victor Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor.[1] When the Liberals came to power under Henry Campbell-Bannerman in December 1905, Beauchamp was appointed Captain of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms[5] and was sworn of the Privy Council in January 1906.[6] In July 1907, he became Lord Steward of the Household,[7] a post he retained when H. H. Asquith became Prime Minister in 1908. He entered the cabinet as Lord President of the Council in June 1910,[8] a post that he held until November of the same year, when he was appointed First Commissioner of Works.[9]

Identified with the radical wing of the Liberal Party, Beauchamp also chaired (in December 1913) the Central Land and Housing Council, which was designed to advance Lloyd George's Land Campaign.[10] He was again Lord President of the council from 1914 to 1915.[11] However, he was not a member of the coalition government formed by Asquith in May 1915. Lord Beauchamp never returned to ministerial office but was the Liberal leader in the House of Lords from 1924 to 1931, supporting the ailing party with his substantial fortune.

While serving in Parliament, Beauchamp also voiced his support for a range of progressive measures such as workmen's compensation,[12] an expansion in rural housing provision, an agricultural minimum wage,[13] improved safety standards[14] and reduced working hours for miners.[15]

Other public appointments

Beauchamp was appointed Honorary Colonel of the 1st Worcestershire Royal Garrison Artillery (Volunteers) on 5 November 1902.[16]

He was made Lord Lieutenant of Gloucestershire in 1911, carried the Sword of State at the coronation of King George V, was made Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1913 and a Knight of the Garter in 1914. He was also Chancellor of the University of London and a Six Master (Governor of RGS Worcester).

In June 1901, Beauchamp received an honorary Doctor of Laws (LLD) degree from the University of Glasgow.[17]

Sexuality and blackmail

In 1931, Lord Beauchamp was "outed" as a homosexual.[18] Although Beauchamp's homosexuality was an open secret in parts of high society and one that his political opponents had refrained from using against him despite its illegality, Lady Beauchamp was oblivious to it and professed a confusion as to what homosexuality was when it was revealed.[2] At one stage she thought her husband was being accused of being a bugler.[19] He had numerous affairs at Madresfield and Walmer Castle, with his partners ranging from servants to socialites, including local men.[2]

In 1930, while on a trip to Australia, it became common knowledge in London society that one of the men escorting him, Robert Bernays, a member of the Liberal Party, was a lover.[2]

It was reported to King George V and Queen Mary by Beauchamp's Tory brother-in-law, the Duke of Westminster, who hoped to ruin the Liberal Party through Beauchamp, as well as Beauchamp personally due his private dislike of Beauchamp.[2] Homosexual practice was a criminal offence at the time, and the King was horrified, rumoured to have said, "I thought men like that shot themselves".[2]

The King had a personal interest in the case, as his sons Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Prince George, Duke of Kent, had visited Madresfield in the past. George was then in a relationship with Beauchamp's daughter Mary, which was cut off by her father's outing.[2]

After sufficient evidence had been gathered by the Duke, Beauchamp was made an offer to separate from his wife Lettice, retire on a pretence and then leave the country. Beauchamp accepted and left the country immediately, living a nomadic life in the global homosexual hotspots of the time.[20] Shortly afterwards, the Countess Beauchamp obtained a divorce.[2] There was no public scandal, but Lord Beauchamp resigned all his offices. Following his departure for the continent, his brother-in-law sent him a note which read. "Dear Bugger-in-law, you got what you deserved. Yours, Westminster."[21]

Lord Beauchamp's last partner was David Smyth (né Glory Smyth-Pigott: son of John Smyth-Pigott, second leader of the messianic sect the Agapemonites), to whom he left a Sydney mansion and share portfolio.[22]

Literary inspiration

Lord Beauchamp is generally supposed to have been the model for Lord Marchmain in Evelyn Waugh's novel, Brideshead Revisited. They were both aristocrats in exile, though for different reasons.[23]

In his 1977 book, Homosexuals in History, historian A. L. Rowse suggests that Beauchamp's failed appointment as Governor of New South Wales was the inspiration for Hilaire Belloc's satirical children's poem, "Lord Lundy", which has in its final lines a command to Lord Lundy from his aged grandfather: "But as it is!...My language fails! Go out and govern New South Wales!". Nevertheless, says Rowse, "Lord Lundy's chronic weakness was tears. This was not Lord Beauchamp's weakness: he enjoyed life, was always gay."[18]

Family

.png.webp)

Lord Beauchamp married at Eccleston, Cheshire, on 26 July 1902 Lady Lettice Grosvenor, daughter of Victor Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor, and Lady Sibell Lumley, and granddaughter of the 1st Duke of Westminster.[24] They had three sons and four daughters:

- William Lygon, 8th Earl Beauchamp (3 July 1903 – 3 January 1979), the last Earl Beauchamp. His widow, Mona, née Else Schiewe, died in 1989.

- The Hon. Hugh Patrick Lygon (2 November 1904 – 19 August 1936, Rothenburg, Bavaria), said to be the model for Lord Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited.

- Lady Lettice Lygon (16 Jun 1906–1973), who married 1930 (div. 1958) Sir Richard Charles Geers Cotterell, 5th Bt. (1907–1978) and had children.

- Lady Sibell Lygon (10 October 1907 – 31 October 2005), who married 11 February 1939 (bigamously) and 1949 (legally) Michael Rowley (d. 19 September 1952), stepson of her maternal uncle, the 2nd Duke of Westminster.[25]

- Lady Mary Lygon (12 February 1910 – 27 September 1982), who married 1937 (div.) HH Prince Vsevolod Ivanovich of Russia, and had no children.

- Lady Dorothy Lygon (22 February 1912 – 13 November 2001),[26] who married 1985 (sep.) Robert Heber-Percy (d. 1987) of Faringdon, Berkshire.

- The Hon. Richard Edward Lygon (25 December 1916 – 1970), who married 1939 Patricia Janet Norman; their younger daughter Rosalind Lygon, now Lady Morrison (b. 1946), inherited Madresfield Court in 1979.

Lord Beauchamp died of cancer in New York City in 1938, aged 66. He was succeeded in the earldom by his eldest son, William. The children never made peace with their mother for her role in the downfall of their father; Lady Beauchamp, "having always being disliked and now hated by her children" was evicted from Madresfield Court by her daughters and spent the remainder of her life at her brother's estate in Cheshire. Lady Beauchamp died in 1936, aged 59, estranged from all her children except her youngest child.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Hazlehurst, Cameron (1979). "Beauchamp, seventh Earl (1872–1938)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 7. Australian National University: Melbourne University Press. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Byrne, Paula (9 August 2009). "Sex scandal behind Brideshead Revisited". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ↑ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen: Suspects, Strays and Guests, Alchemie Books, 2023, pp. 234-235.

- ↑ "CanonN W. I. Carr Smith". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW: National Library of Australia. 5 July 1930. p. 19. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "No. 27877". The London Gazette. 23 January 1906. p. 541.

- ↑ "No. 27873". The London Gazette. 9 January 1906. p. 182.

- ↑ "No. 28046". The London Gazette. 30 July 1907. p. 5281.

- ↑ "No. 28386". The London Gazette. 21 June 1910. p. 4366.

- ↑ "No. 28435". The London Gazette. 8 November 1910. p. 7979.

- ↑ Dutton, David. "Biographies: William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp (1872–1938)" (PDF). liberahistory.org.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "No. 28862". The London Gazette. 4 August 1914. p. 6165.

- ↑ "Workmen's Compensation Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 14 December 1906. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Housing of the Working Classes". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 28 April 1914. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Mines Accidents (Rescue and Aid) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 25 July 1910. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Coal Mines (Eight Hours) Bill". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 15 December 1908. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "No. 27491". The London Gazette. 4 November 1902. p. 7017.

- ↑ "Glasgow University jubilee". The Times. No. 36481. London. 14 June 1901. p. 10. Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 A. L. Rowse, Homosexuals in History (1977), pp. 222–223 ISBN 0-88029-011-0

- ↑ Eade, Philip (2017). Evelyn Waugh: A life revisited. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 160. ISBN 9781250143297. Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Bloch, Michael (2015). Closet Queens. Little, Brown. p. 21. ISBN 978-1408704127.

- ↑ Tinniswood, Adrian (2016). The Long Weekend: Life in the English Country House Between the Wars. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 260. ISBN 9780224099455.

- ↑ Jordaan, Peter, A Secret Between Gentlemen: Suspects, Strays and Guests, Alchemie Books, 2023, p. 263-264.

- ↑ Mulvagh, Jane (24 May 2008). "Evelyn Waugh: a blueprint for Brideshead". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36831. London. 28 July 1902. p. 9. Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Lady Sibell Rowley" (obituary) Daily Telegraph, 16 November 2005.

- ↑ "Obituaries: Lady Dorothy Heber Percy". The Daily Telegraph. 17 November 2001.

- ↑ "The scandal that shook Brideshead. "..back in England, Lady Beauchamp was even more isolated. Estranged from all her children, save for Dickie, she led a pitiful existence: alone, confused, ill and in thrall to her bullying brother. Lady Beauchamp's children never made peace with her. She died in 1936, five years after her husband's flight. She was only 59."

Bibliography

- Bloch, Michael (2015). Closet Queens. Little, Brown. ISBN 1408704129 Chapter 1

- Dutton, David (Summer 1999). "William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp (1872–1938)" (PDF). Journal of Liberal History (23). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Hazlehurst, Cameron (1979). "Beauchamp, seventh Earl (1872–1938)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. 7.

- Charles Hobhouse (1971). Edward David (ed.). Inside Asquith's Cabinet: The Political Diaries of Charles Hobhouse. London: John Murray. ISBN 0719533872.

- Jordaan, Peter (2023). A Secret Between Gentlemen: Suspects, Strays and Guests. Sydney: Alchemie Books. ISBN 9780645852745.

- Mulvagh, Jane (2009). Madresfield: The Real Brideshead. Oxford: ISIS. ISBN 9780753183380.

- Raina, Peter (2016). The Seventh Earl Beauchamp: A Victim of His Times. Lausanne: Peter Lang. ISBN 9781906165628.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- Portrait of the 7th Earl (1899), by Sir Leslie Ward for Vanity Fair. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- Article on Lygon's influence on the plot for Brideshead Revisited