Lev Alexandrovich Russov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 31 January 1926 |

| Died | 20 February 1987 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Tavricheskaya Art School, Repin Institute of Arts |

| Known for | Painting, Graphics, Sculpture |

| Notable work | Portrait of Catherine Balebina |

| Movement | Realism |

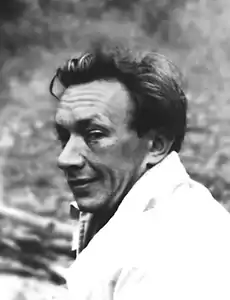

Lev Alexandrovich Russov (Russian: Ле́в Алекса́ндрович Ру́сов; 31 January 1926 – 20 February 1987) was a Soviet Russian painter, graphic artist, and sculptor, living and working in Leningrad, a member of the Leningrad Union of Artists[1] and representative of the Leningrad school of painting,[2] most known for his portrait painting.

Biography

Lev Alexandrovich Russov was born on 31 January 1926 in Leningrad, into a family of employees. His father Alexander Semionovich Russov came from peasants of the Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, his mother Iraida Semionovna Nemtsova was from Kostroma. In 1939, passion for drawing leads Russov to the art studio of the Vyborgsky district of Leningrad, where he is engaged up to the outbreak of war.

In December 1941, along with his mother he was evacuated from the siege of Leningrad in the Gorky Province. Soon he had an accident that could change the fate of the future artist. Under circumstances not completely clear, Rusov lost his right eye. According to the artist's son, this happened from a careless jab of whip. However already 1943, he moved to Kostroma city, where goes to the regional art school.

In 1945, in connection with the return to Leningrad Russov was transferred to Tavricheskaya Art School (now known as an Art College named after Nicholas Roerich), from which he graduated in 1947.[3]

After graduation Russov entered the first course of Painting Department of Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture named after Ilya Repin, studied of Yuri Neprintsev and Genrikh Pavlovsky. However, having studied for two years for health reasons had to leave class. In 1951–1955 Russov taught drawing in the secondary schools of Leningrad, while continuing to work on his painting skills using the experience gained while studying at the Academy.[4]

Soon Russov shows his work in Leningrad Union of Artists and he is invited to participate in art exhibitions together with leading masters of the fine arts of Leningrad. At the Spring Art Exhibitions of 1954 and 1955, he presented works A Girl with a Bow[5] (1954), A Boy and a Sea and Portrait of artist Veniamin Kremer[6] (both 1955) to attract attention to himself as a talented portrait painter.

In 1955, Russov was admitted to the Leningrad Union of Soviet artists on the recommendations of the famous painters Piotr Buchkin, Yuri Neprintsev and Veniamin Kremer. In addition to portraits, Russov during these years painted genre compositions, still lifes, landscapes, worked in the technique of oil painting, watercolors and woodcuts.

The year 1955 was marked for Russov by meetings with people who changed his personal and creative destiny. He meets Ekaterina Vasilievna Balebina (born 29 December 1933, the daughter of Vasily Balebin, the famous torpedo bomber, Hero of the Soviet Union), who will soon become his wife, the mother of his son Andrei and the main muse. Charming and lively, full of self-sacrifice, she will serve for Russov as a model for many paintings and portraits, create and protect the world in which the artist's creative gift will unfold and sparkle in full strong.

In the same year, Lev Russov met with Yevgeny Mravinsky, their relationship grew into a long-years friendship, to which we owe several portraits of the outstanding conductor, created during 1950-1980s.

In 1960–1980 Russov creative life was divided between the Leningrad art studio, the home in Fonarny Lane and the village of Pavshino on the Oredezh River, where on the high bank of the river he built a cottage with a workshop and worked many months each year.

Lev Alexsandrovich Russov died on 20 February 1987 in Leningrad in the sixty-second year of his life from heart disease. His works reside in museums and private collections in Russia, US, Norway, Great Britain, Sweden, France and other countries. The widow of the artist Ekaterina Vasilievna Russov outlived her husband by 15 years and died on June 20, 2002, in St. Petersburg at the sixty-ninth year of life.

In 1970, at the Leningrad Physical-Technical Institute named after A.F. Ioffe, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, it consisted of the only lifetime exhibition of Russov's works

Creativity

The creative life of Lev Russov, unusual and contradictory, contained two periods of unequal length and significance, one of which was devoted to painting, and the other mainly to wooden sculpture.

Portrait

According to the researchers of the artist's creativity, with the full strength Russov's pictorial talent was revealed in a series of portraits of his contemporaries painted in the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s, which brought fame and recognition to the author. For ten years, Russov created a gallery of portraits that enriched the various types of modern portraiture. The beginning of it was laid on female images, among which portraits of the wife and young women from the circle of common friends stand out. Among them were Portrait of Catherine Balebina[7][8] (1956), Portrait of Natali Orlova[9] (1956), Portrait of Young Woman in Red (1956), Portrait of Young Woman (1957), and others.

The known art works that continued them in the late 1950s and early 1960s – Portrait of wife (1959), Fresh Model (1961), Kira, Narine, Portrait of Maria Korsukova (all 1962), is distinguished by great decorativeness, generalization of the drawing and the sharpness of the composition, which Russov used in searching for means of enhancing the expressiveness of the image.

Characterizing the work of Russov, art historians Anatoli Dmitrenko and Ruslan Bakhtiyarov note:

In Leningrad portrait-painting at the turn of the 1960s a certain conflict still persisted between the task of producing a typified image and the simultaneous desire on the part of the artist to touch upon “the hidden movements of the soul”. It is no coincidence that Lev Russov, who gave unambiguous preference in his work to the latter aspect, separated, as it were, the subject's inner world from the outward predetermined features of the type that marked many works of portraiture. In his paintings one can trace a connection with the work of Valentin Serov and the manner of Osip Braz and Andreas Zorn. Organically connecting the figure and the background, which he successfully used as a means of heightening the expressiveness of the image, Russov at the same time accords each of his subjects the right to “personal space”, as, for example, in the portraits of Ekaterina Balebina, Natalya Orlova or the young country girl Natasha Savelyeva.[10]

Trips in the mid-1950s to Oredezh, first to Nakol village, and then to Pavshino, marked the beginning of a remarkable series of portraits of children and young people. Among them Zoya (1957), twin portrait of sisters Kira and Zoya (1958), Natasha (1958), Natasha, Little Bows (обе 1960). In the 1960s, this series of works was supplemented by portraits of the son Andrei with the Horse (1963), Portrait of the Son (1965) and others.

The portraits of this period fall at the time of the highest creative upsurge of Russov as the painter, and constitute the most valuable part of his diverse artistic heritage. They are distinguished by an extraordinary expressiveness of images, courage of compositional decisions, unmistakable artistic taste. The color scheme is dominated by pearl and purple tones. The manner of the artist is distinguished by a powerful pictorial language, wide writing, sharp composition, interest in unexpected rakurs. Rusov possessed a rare ability to capture the fleeting states of model, to quickly embody a pictorial idea on canvas – immediately and unusually convincingly. The images he created combine the expressiveness of individual characteristics with a vivid embodiment of the typical features of contemporaries.

In the work on the portrait, Rusov manages to grab the fleeting state of model, which, with prolonged posing, eludes most artists. He knows how to keep this first impression to the end and convey to the viewer. Therefore, in his works, nature is alive, and this feeling of a lively look of living people is almost the most exciting in the artist's portraits.[11]

Along with the expressiveness of the form, the portraits of Russov are distinguished by the depth and psychologism of the images, careful selection and study of model. Its another important reason for the success of his works. Some of his best works of this period Russov painted in the village of Pavshino on the Oredezh River near Leningrad, where in the late 1950s a group of young artists settled: G. Bagrov, E. Shram, K. Slavin and N. Slavina, L. Kuzov, A. Yakovlev, G. Antonov. Here on the Oredezh river, first in the village of Nakol, then in Pavshino Rusov finds the heroines of her new portraits: Aunt Polya, the sisters Zoya and Kira, the village girl Natasha Savelyeva. It was her portrait, painted by Rusov in 1958, for the first time that was truly noticed and appreciated by critics.

In critical reviews of the Fall Art Exhibition of 1958, Leningrad newspapers gave this portrait a prominent place. E. Kovtun, in his article Notes on an Art Exhibition in the newspaper Leningrad Evening dated 29 November 1958, wrote about the amazing immediacy and freshness of feelings that bribes in this work of L. Russov.[12] M. Shumova in the article Do not surrender the won borders! in Leningrad Pravda of 2 December 1958, wrote about this work:

Portrait "Natasha" by Lev Russov pleases of the sincere interest of the artist in the inner world of man. The background of the portrait and the dress of the girl are done with sweeping, strong strokes. But they do not catch the eye, do not lead away from the shaded face, which was also written fluently, but at the same time carefully, subtly, thoughtfully. The girl's inquisitive eyes, her inspired face attract attention.[13]

In the same years, Russov painted of known art workers, as well as workers and collective farmers. Among them Portrait of Young Collective Farmer (1956), Portrait of Yevgeny Mravinsky (1957),[14] Portrait of Actor Vladislav Strzhelchik (1957),[15] Portrait of Young Caster (1961),[16] Aunt Pola with hen (1961), Stell-Maker (1972), and others. In a male portrait, regardless of the social status of the model, the artist is attracted by strong independent persons.

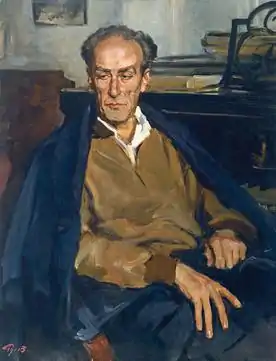

Mravinsky

Russov's acquaintance with Yevgeny Mravinsky in 1955 quickly grew into a friendship that lasted until the end of the artist's life. For thirty years, Rusov painted several portraits of the outstanding conductor, the most famous of which is A Portrait of E. A. Mravinsky of 1957.

The portrait was painted by Rusov for two years and was completed in 1957. In the same year it was first shown at the anniversary exhibition in the State Russian Museum.[17] Unlike most famous portraits, Mravinsky is depicted in a home environment, when a person belongs only to himself and reveals himself in his true guise.

From the Memoirs of Alexander Mikhailovna Vavilina-Mravinsky, the widow of Yevgeny Mravinsky:

Among the only few friends of Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Mravinsky, who had the right to ring the door of the apartment without prior arrangement by phone, was Lyovushka Russov — that was what he was called in our house. Is appeared – as if he just dropped out the sky! At any time of the day – a phenomenon ordinary to the owners.

His coming always brought light, a smile, joy and unselfish communication into life. Yevgeny Alexsandrovich's acquaintance and friendship with Leva Russov was measured for decades, and therefore the atmosphere of the conversations was sincere and simple. Lyovushka was aware of all of Yevgeny Aleksandrovich's creative and everyday experiences, he loved music, knew it, had an excellent memory and refined taste.

At meetings, both, as a rule, rushed to talk about nature, about fishing (fishing rods, lures, tackle, etc.), since life outside the city was for both as the basis of creative charge, a source of spiritual reserves. lively by nature, temperamental and talkative, Lyovushka Russov had a grateful listener and narrator in the face of Yevgeny Alexandrovich. These parties, of course, were slightly accompanied by vodka and Prishvin-style stories until late at night..[18]

In the 1970s, Russov turned to the theme of two great contemporaries – Dmitry Shostakovich and Yevgeny Mravinsky, she found its embodiment in the picture The Leningrad Symphony. Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky (1980). Russov worked for a long time on the concept and composition of the picture, rejecting one option after another. It is difficult to judge the extent to which its final version satisfied the artist. It can be assumed that, if he had the strength and time, this work could continue.

From the Memoirs of Alexander Mikhailovna Vavilina-Mravinsky, the widow of Yevgeny Mravinsky:

Lev Russov had another desirable dream-topic: Mravinsky and Shostakovich, but the disease, lack of life time and energy did not allow to realize it in its final form. Leva and Yevgeny Alexsandrovich talked for a long time and more than once about the method of implementing this idea, but this topic is so monumental, just as unrealizable, depending on the God-given times for both..[19]

Thyl Ulenspiegel

In the years 1954–1956 Lev Russov was drawn to the historical genre, creating a series of eight paintings on the novel by Charles de Coster's The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel. Choosing a theme and its figurative embodiment echoed the mood of the Khrushchev "Thaw and personal freedom-loving aspirations of the author. Shown at the end of 1956 at the Autumn exhibition of Leningrad artists works A Birth, On Tortures, A Death of father, On the Fields of the Motherland, A Boarding (Insurgent Flandria), Till and Lamme, Death to traitors, Song by Till (all 1956), first brought the author fame and claimed him as a master of historical painting.[20][21]

These works, and above all the double portrait of Till and Lamme,[22] are also interesting in that the artist gave Thill features a close resemblance to the author. This makes it unique in the creative legacy of the artist as self-portraits of Lev Russov are unknown. As a child he lost one eye and did not like to be photographed and a general refusal to pose for portraits, painted by himself or others.

In the future, Russov's interest in historical topics was expressed in numerous works of wooden sculpture, as well as in a some paintings, in particular in the painting Strolling Buffoons (1976).

Still-Life

Still-life in the works of Russov is closely connected with the colorful and compositional tasks that the artist set for himself in the work on the portrait. Hence the sharpness and freshness of compositional solutions, the internal dramatic and tension in his works of this genre. It is no coincidence that, in terms of expressiveness and depth of images, the best works by Russov in the still life genre are not inferior to his well-known portraits. This sets them apart from others paintings created in this genre in 1950–1970.

Most of his still lifes convey not only the interior of the artist's workshop and the object world surrounding him, but also the atmosphere, the flour of creativity in which the creator's ideas are born and implemented. Moreover, their art form, despite the apparent ease of execution, is thought out and brought to perfection by the author. Among Russov's works in this genre, sources distinguish Still-Life with Seneca[23] (1963), Still-Life with Bouquet[24] (1959), Music and Violin[25] (1964), Art Studio. Still-Life[26] (1979), and others.

The works of the 1950-1960s moved Lev Russov into the leading masters of portraiture. However, for the general public and even for many colleagues in the Leningrad Union of Artists, he remained virtually unknown. The explanation for this must be sought primarily in the character traits of the artist. A man of independent views, talented, direct, sometimes ruthless in assessments and judgments, astonishing those who knew him closely with his monstrous capacity for work, he eschewed the public life of the Union of Artists, was intolerant of any manifestations of mediocrity and imitation of creativity. In fact, during the Brezhnev years of stagnation and developed socialism he remained a man of the Khrushchev's thaw. In 1970–1980 Russov rarely showed his work at art exhibitions. His life was divided between a city workshop, a house in Pavshino on Oredezh and communication with a narrow circle of old friends. In fairness, we must admit that the existing system did not reject such artists, allowing them to have almost free materials and a workshop for creative work in exchange for minimal loyalty.

In mid-1960s Lev Russov enjoys wooden sculpture and Russian folk epic. From now until the end of life it becomes the main theme of his work, surpassing the painting. From his hands came out a lot of superb sculptures, from small figurines to large forms, such as Russian Icarus and the relief on the epic theme of Zastava, Folk singers.

Family

- Wife Ekaterina Vasilievna Balebiba (1933–2002);

- Son Andrei Lvovich Russov (b. 1960).

See also

References

- ↑ Directory of Members of the Union of Artists of USSR. Vol. 2. Moscow, Soviet artist, 1979. P.290.

- ↑ The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. P.354. ISBN 978-5-6042574-2-5

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. St Petersburg, NP-Print, 2007. P.368

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. Riddles early portraits by Lev Russov.

- ↑ The Spring Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1954. Exhibition Catalogue. Leningrad, Leningrad Union of Artists, 1954. P.17.

- ↑ The Spring Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1955. Catalogue. Leningrad, Leningrad Union of Artists, 1956. P.16.

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. St Petersburg, NP-Print, 2007. P.65.

- ↑ [The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. Plate 40.]

- ↑ Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. St Petersburg, NP-Print, 2007. P.151.

- ↑ Аnatoli F. Dmitrenko, Ruslan A. Bakhtiyarov. The Leningrad School and the Realistic Tradition of Russian Painting // The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg: ARKA Gallery Pudlishing, 2019. P.61-64.

- ↑ Иванов С. В. Загадки ранних портретов Льва Русова.

- ↑ Ковтун Е. Заметки о художественной выставке // Вечерний Ленинград, 1958, 29 ноября.

- ↑ Шумова М. Не уступать завоёванных рубежей! // Ленинградская правда, 1958, 2 декабря.

- ↑ Русов Л. А. Портрет Е. А. Мравинского // 80 лет Санкт-Петербургскому Союзу художников. Юбилейная выставка. СПб, Цветпринт, 2012. С.208.

- ↑ 1917–1957. Выставка произведений ленинградских художников. Каталог. Л., Ленинградский художник, 1958. С.28.

- ↑ Выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1961 года. Каталог. Л., Художник РСФСР, 1964. С.34.

- ↑ 1917–1957. Выставка произведений ленинградских художников. Каталог. Л., Ленинградский художник, 1958. С.28.

- ↑ Иванов С. В. О ранних портретах Льва Русова. // Петербургские искусствоведческие тетради. Выпуск 23. СПб., 2012. С.11.

- ↑ Иванов С. В. О ранних портретах Льва Русова. // Петербургские искусствоведческие тетради. Выпуск 23. СПб., 2012. С.12.

- ↑ The Fall Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1956. Exhibition Catalogue. Leningrad, The Leningrad Artist, 1958. P.21.

- ↑ The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. P.240-241. ISBN 978-5-6042574-2-5

- ↑ The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. Plate 195.

- ↑ Иванов С. Неизвестный соцреализм. Ленинградская школа. СПб, НП-Принт, 2007. С.22. ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7

- ↑ The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. С.251, 327, 333.

- ↑ The Leningrad School of Painting. Essays on the History. St Petersburg, ARKA Gallery Publishing, 2019. С.209, 327, 332.

- ↑ Иванов С. Неизвестный соцреализм. Ленинградская школа. СПб, НП-Принт, 2007. С.171. ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7

Principal exhibitions

- 1954 (Leningrad): The Spring Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1954

- 1955 (Leningrad): The Spring Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1955

- 1956 (Leningrad): The Fall Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1956

- 1957 (Leningrad): 1917–1957. Leningrad Artist's works of Art Exhibition

- 1958 (Leningrad): The Fall Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1958

- 1960 (Leningrad): Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1960

- 1961 (Leningrad): Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1961

- 1980 (Leningrad): Regional Exhibition of works by Leningrad artists of 1980

- 1994 (Saint Petersburg): Paintings of 1950-1980s by the Leningrad School artists

- 1994 (Saint Petersburg): Etudes from the life in creativity of the Leningrad School's artists

- 1995 (Saint Petersburg): Lyrical motives in the works of artists of the war generation

- 1996 (Saint Petersburg): Paintings of 1940-1990s. The Leningrad School

- 1997 (Saint Petersburg): "Still life in Painting of 1950-1990s. The Leningrad School"

Bibliography

- Центральный Государственный Архив литературы и искусства. СПб. Ф.78. Оп.8. Д.141.

- Весенняя выставка произведений ленинградских художников. Каталог. Л., Изогиз, 1954. С.17.

- Весенняя выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1955 года. Каталог. Л., ЛССХ, 1956. С.16.

- Осенняя выставка произведений ленинградских художников. 1956 года. Каталог. Л., Ленинградский художник, 1958. С.21.

- 1917–1957. Выставка произведений ленинградских художников. Каталог. Л., Ленинградский художник, 1958. С.28.

- Е. Ковтун. Заметки о художественной выставке // Вечерний Ленинград. 1958, 29 ноября.

- М. Шумова. Не уступать завоёванных рубежей! // Ленинградская правда. 1958, 2 декабря.

- Осенняя выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1958 года. Каталог. Л., Художник РСФСР, 1959. С.23.

- Выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1960 года. Каталог. Л., Художник РСФСР, 1961. С.35.

- Выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1961 года. Каталог. Л., Художник РСФСР, 1964. С.34.

- В. Бойков. И тема и образ. Нева. 1972. No. 1. С. 202—205.

- Зональная выставка произведений ленинградских художников 1980 года. Каталог. Л., Художник РСФСР, 1983. С.22.

- Ленинградские художники. Живопись 1950–1980 годов. Каталог. СПб., 1994. С.6.

- Этюд в творчестве ленинградских художников. Выставка произведений. Каталог. СПб., 1994. С.6.

- Русов Л. А. Зоя // Иванов С. В. Этюд в багровых тонах // Санкт-Петербургские ведомости. 1994, 9 декабря.

- Лирика в произведениях художников военного поколения. Живопись. Графика. Каталог. СПб., 1995. С.6.

- Живопись 1940–1990 годов. Ленинградская школа. Выставка произведений. СПб., 1996. С.4.

- Ленинградская школа // Афиша. Еженедельное приложение к газете Санкт-Петербургские ведомости. 1996, 2 марта.

- Визирякина Т. Эпоха. Время. Художник // Невское зеркало. 1996, No. 7.

- Саблин В. Ленинградская школа в Петербурге // Вечерний Петербург. 1996, 21 марта.

- Натюрморт в живописи 1940–1990 годов. Ленинградская школа. Каталог выставки. СПб., 1997. С.4.

- Славин К., Славина Н. Были мы молоды. СПб., РИД, 2000. ISBN 978-5-89132-016-1.

- Matthew C. Bown. Dictionary of 20th Century Russian and Soviet Painters 1900-1980s. - London: Izomar, 1998. ISBN 0-9532061-0-6, ISBN 978-0-9532061-0-0.

- Данилова А. Становление ленинградской школы живописи и ее художественные традиции // Петербургские искусствоведческие тетради. Вып. 21. СПб, 2011. С.94—105.

- Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School.- Saint Petersburg: NP-Print Edition, 2007. – pp. 12, 15, 24, 28, 368, 414-416, 420, 422-423. ISBN 5-901724-21-6, ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7.

- Русов Л. А. Портрет Е. А. Мравинского // 80 лет Санкт-Петербургскому Союзу художников. Юбилейная выставка. СПб., Цветпринт, 2012. С.208.

- Иванов С. О ранних портретах Льва Русова // Петербургские искусствоведческие тетради. Выпуск 23. СПб., 2012. С.7-15.

- Логвинова Е. Круглый стол по ленинградскому искусству в галерее АРКА // Петербургские искусствоведческие тетради. Вып. 31. СПб, 2014. С.17-26.

External links

- Solo Exhibition of Lev Russov in Museum of Art

- Exhibition of Lev Russov in ARKA Fine Art Gallery

- Mysteries of early portraits of Lev Russov (Rus, En)

- Artist Lev Russov (1926–1987). Masterpieces of Portrait Painting. The Leningrad School. Part 1 (VIDEO)

- Artist Lev Russov (1926–1987). Painting. The Leningrad School. Part 2 (VIDEO)