| Mount Rainier | |

|---|---|

| Tahoma | |

Mount Rainier's northwestern slope viewed aerially just before sunset on September 6, 2020 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 14,411 ft (4,392 m) NAVD 88[1][2] |

| Prominence | 13,246 ft (4,037 m)[1] |

| Parent peak | Mount Massive, United States of America[3] |

| Isolation | 731 mi (1,176 km)[1] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 46°51′10″N 121°45′38″W / 46.8528267°N 121.7604408°W[4] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Peter Rainier |

| Geography | |

Mount Rainier | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Pierce County |

| Protected area | Mount Rainier National Park |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Rainier West |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 500,000 years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1870 by Hazard Stevens and P. B. Van Trump |

| Easiest route | rock/ice climb via Disappointment Cleaver |

Mount Rainier (/reɪˈnɪər/ ray-NEER), also known as Tahoma, is a large active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest in the United States. The mountain is located in Mount Rainier National Park about 59 miles (95 km) south-southeast of Seattle.[5] With a summit elevation of 14,411 ft (4,392 m),[6][7] it is the highest mountain in the U.S. state of Washington, the most topographically prominent mountain in the contiguous United States,[8] and the tallest in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.

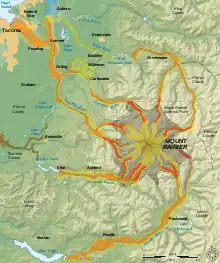

Due to its high probability of an eruption in the near future, Mount Rainier is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world, and it is on the Decade Volcano list.[9] The large amount of glacial ice means that Mount Rainier could produce massive lahars that could threaten the entire Puyallup River valley. According to the United States Geological Survey, "about 80,000 people and their homes are at risk in Mount Rainier's lahar-hazard zones."[10]

Between 1950 and 2018, 439,460 people climbed Mount Rainier.[11][12] Approximately 84 people died in mountaineering accidents on Mount Rainier from 1947 to 2018.[11]

Name

The diverse Indigenous peoples who have lived near Mount Rainier for millennia have many names for the mountain in their various languages.

Lushootseed speakers have several names for Mount Rainier, including xʷaq̓ʷ and təqʷubəʔ.[lower-alpha 1][13] xʷaq̓ʷ means "sky wiper" or "one who touches the sky" in English.[13] The word təqʷubəʔ means "snow-covered mountain".[13][14] təqʷubəʔ has been anglicized in many ways, including 'Tacoma', 'Tahoma', and 'Tacobet'.[15]

Sahaptin speakers call the mountain Taxúma.[16]

Another anglicized name is Pooskaus.[17]

George Vancouver named Mount Rainier in honor of his friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier.[18] The map of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804–1806 refers to it as "Mt. Regniere". Although Rainier had been considered the official name of the mountain, Theodore Winthrop referred to the mountain as "Tacoma" in his posthumously published 1862 travel book The Canoe and the Saddle. For a time, both names were used interchangeably, although residents of the nearby city of Tacoma preferred Mount Tacoma.[19][20]

In 1890, the United States Board on Geographic Names declared that the mountain would be known as Rainier.[21] Following this in 1897, the Pacific Forest Reserve became the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve, and the national park was established three years later. Despite this, there was still a movement to change the mountain's name to Tacoma and Congress was still considering a resolution to change the name as late as 1924.[22][23] After the 2015 restoration of the original name Denali from Mount McKinley in Alaska, debate over Mount Rainier's name intensified.[24]

Geographical setting

Mount Rainier is the tallest mountain in Washington and the Cascade Range. This peak is located just east of Eatonville and just southeast of Tacoma and Seattle.[25] Mount Rainier is ranked third of the 128 ultra-prominent mountain peaks of the United States. Mount Rainier has a topographic prominence of 13,210 ft (4,026 m), which is greater than that of K2, the world's second-tallest mountain, at 13,189 ft (4,020 m).[26] On clear days it dominates the southeastern horizon in most of the Seattle-Tacoma metropolitan area to such an extent that locals sometimes refer to it simply as "the Mountain".[27] On days of exceptional clarity, it can also be seen from as far away as Corvallis, Oregon (at Marys Peak), and Victoria, British Columbia.[28]

With 26 major glaciers[29] and 36 sq mi (93 km2) of permanent snowfields and glaciers,[30] Mount Rainier is the most heavily glaciated peak in the lower 48 states. The summit is topped by two volcanic craters, each more than 1,000 ft (300 m) in diameter, with the larger east crater overlapping the west crater. Geothermal heat from the volcano keeps areas of both crater rims free of snow and ice, and has formed the world's largest volcanic glacier cave network within the ice-filled craters,[31] with nearly 2 mi (3.2 km) of passages.[32] A small crater lake about 130 by 30 ft (39.6 by 9.1 m) in size and 16 ft (5 m) deep, the highest in North America with a surface elevation of 14,203 ft (4,329 m), occupies the lowest portion of the west crater below more than 100 ft (30 m) of ice and is accessible only via the caves.[33][34]

The Carbon, Puyallup, Mowich, Nisqually, and Cowlitz Rivers begin at eponymous glaciers of Mount Rainier. The sources of the White River are Winthrop, Emmons, and Fryingpan Glaciers. The White, Carbon, and Mowich join the Puyallup River, which discharges into Commencement Bay at Tacoma; the Nisqually empties into Puget Sound east of Lacey; and the Cowlitz joins the Columbia River between Kelso and Longview.

Subsidiary peaks

The broad top of Mount Rainier contains three named summits. The highest is called the Columbia Crest. The second highest summit is Point Success, 14,158 ft (4,315 m), at the southern edge of the summit plateau, atop the ridge known as Success Cleaver. It has a topographic prominence of about 138 ft (42 m), so it is not considered a separate peak. The lowest of the three summits is Liberty Cap, 14,112 ft (4,301 m), at the northwestern edge, which overlooks Liberty Ridge, the Sunset Amphitheater, and the dramatic Willis Wall.[35] Liberty Cap has a prominence of 492 ft (150 m), and so would qualify as a separate peak under most strictly prominence-based rules. A prominence cutoff of 400 ft (122 m) is commonly used in Washington state.[36]

High on the eastern flank of Mount Rainier is a peak known as Little Tahoma Peak, 11,138 ft (3,395 m), an eroded remnant of the earlier, much higher, Mount Rainier. It has a prominence of 858 ft (262 m), and it is almost never climbed in direct conjunction with Columbia Crest, so it is usually considered a separate peak. If considered separately from Mount Rainier, Little Tahoma Peak would be the third highest mountain peak in Washington.[37][38]

Geology

Mount Rainier is a stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc that consists of lava flows, debris flows, and pyroclastic ejecta and flows. Its early volcanic deposits are estimated at more than 840,000 years old and are part of the Lily Formation (about 2.9 million to 840,000 years ago). The early deposits formed a "proto-Rainier" or an ancestral cone prior to the present-day cone.[39] The present cone is more than 500,000 years old.[40]

The volcano is highly eroded, with glaciers on its slopes, and appears to be made mostly of andesite. Rainier likely once stood even higher than today at about 16,000 ft (4,900 m) before a major debris avalanche and the resulting Osceola Mudflow approximately 5,000 years ago.[41] In the past, Rainier has had large debris avalanches, and has also produced enormous lahars (volcanic mudflows), due to the large amount of glacial ice present. Its lahars have reached all the way to Puget Sound, a distance of more than 30 mi (48 km). Around 5,000 years ago, a large chunk of the volcano slid away and that debris avalanche helped to produce the massive Osceola Mudflow, which went all the way to the site of present-day Tacoma and south Seattle.[42] This massive avalanche of rock and ice removed the top 1,600 ft (500 m) of Rainier, bringing its height down to around 14,100 ft (4,300 m). About 530 to 550 years ago, the Electron Mudflow occurred, although this was not as large-scale as the Osceola Mudflow.[43]

After the major collapse approximately 5,000 years ago, subsequent eruptions of lava and tephra built up the modern summit cone until about as recently as 1,000 years ago. As many as 11 Holocene tephra layers have been found.[39]

Soils on Mount Rainier are mostly gravelly ashy sandy loams developed from colluvium or glacial till mixed with volcanic tephra. Under forest cover their profiles usually have the banded appearance of a classic podzol but the E horizon is darker than usual. Under meadows a thick dark A horizon usually forms the topsoil.[44]

Modern activity and threat

The most recent recorded volcanic activity was between 1820 and 1854, but many eyewitnesses reported eruptive activity in 1858, 1870, 1879, 1882, and 1894 as well.[45] Additionally, the Smithsonian Institution's volcanism project records the last volcanic eruption as 1450 CE.[46]

Seismic monitors have been placed in Mount Rainier National Park and on the mountain itself to monitor activity.[47] An eruption could be deadly for all living in areas within the immediate vicinity of the volcano and an eruption would also cause trouble from Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada to San Francisco, California[48] because of the massive amounts of ash blasting out of the volcano into the atmosphere.

Mount Rainier is located in an area that itself is part of the eastern rim of the Pacific Ring of Fire. This includes mountains and calderas like Mount Shasta and Lassen Peak in California, Crater Lake, Three Sisters, and Mount Hood in Oregon, Mount St. Helens, Mount Adams, Glacier Peak, and Mount Baker in Washington, and Mount Cayley, Mount Garibaldi, Silverthrone Caldera, and Mount Meager in British Columbia. Many of the above are dormant, but could return to activity, and scientists on both sides of the border gather research of the past eruptions of each in order to predict how mountains in this arc will behave and what they are capable of in the future, including Mount Rainier.[49][50] Of these, only two have erupted since the beginning of the twentieth century: Lassen in 1915 and St. Helens in 1980 and 2004. However, past eruptions in this volcanic arc have multiple examples of sub-plinian eruptions or higher: Crater Lake's last eruption as Mount Mazama was large enough to cause its cone to collapse,[51] and Mount Rainier's closest neighbor, Mount St. Helens, produced the largest eruption in the continental United States when it erupted in 1980. Statistics place the likelihood of a major eruption in the Cascade Range at 2–3 per century.[52]

Mount Rainier is listed as a Decade Volcano, or one of the 16 volcanoes with the greatest likelihood of causing loss of life and property if eruptive activity resumes.[53] If Mount Rainier were to erupt as powerfully as Mount St. Helens did in its May 18, 1980 eruption, the effect would be cumulatively greater, because of the far more massive amounts of glacial ice locked on the volcano compared to Mount St. Helens,[43] the vastly more heavily populated areas surrounding Rainier, and the fact that Mount Rainier is almost twice the size of St. Helens.[54] Lahars from Rainier pose the most risk to life and property,[55] as many communities lie atop older lahar deposits. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), about 150,000 people live on top of old lahar deposits of Rainier.[10] Not only is there much ice atop the volcano, the volcano is also slowly being weakened by hydrothermal activity. According to Geoff Clayton, a geologist with a Washington State Geology firm, RH2 Engineering, a repeat of the 5000-year-old Osceola Mudflow would destroy Enumclaw, Orting, Kent, Auburn, Puyallup, Sumner and all of Renton.[42] Such a mudflow might also reach down the Duwamish estuary and destroy parts of downtown Seattle, and cause tsunamis in Puget Sound and Lake Washington.[56] Rainier is also capable of producing pyroclastic flows and expelling lava.[56]

According to Kevin Scott, a scientist with the USGS:

A home built in any of the probabilistically defined inundation areas on the new maps is more likely to be damaged or destroyed by a lahar than by fire... For example, a home built in an area that would be inundated every 100 years, on the average, is 27 times more likely to be damaged or destroyed by a flow than by fire. People know the danger of fire, so they buy fire insurance and they have smoke alarms, but most people are not aware of the risks of lahars, and few have applicable flood insurance.[57]

The volcanic risk is somewhat mitigated by lahar warning sirens and escape route signs in Pierce County.[58] The more populous King County is also in the lahar area, but has no zoning restrictions due to volcanic hazard.[59] More recently (since 2001) funding from the federal government for lahar protection in the area has dried up, leading local authorities in at-risk cities like Orting to fear a disaster similar to the Armero tragedy.[60][61]

Seismic background

Typically, up to five earthquakes are recorded monthly near the summit. Swarms of five to ten shallow earthquakes over two or three days take place from time to time, predominantly in the region of 13,000 feet (4 km) below the summit. These earthquakes are thought to be caused by the circulation of hot fluids beneath Mount Rainier. Presumably, hot springs and steam vents within Mount Rainier National Park are generated by such fluids.[62] Seismic swarms (not initiated with a mainshock) are common features at volcanoes, and are rarely associated with eruptive activity. Rainier has had several such swarms; there were days-long swarms in 2002, 2004, and 2007, two of which (2002 and 2004) included M 3.2 earthquakes. A 2009 swarm produced the largest number of events of any swarm at Rainier since seismic monitoring began over two decades earlier.[63] Further swarms were observed in 2011 and 2021.[64][65]

Glaciers

Glaciers are among the most conspicuous and dynamic geologic features on Mount Rainier. They erode the volcanic cone and are important sources of streamflow for several rivers, including some that provide water for hydroelectric power and irrigation. Together with perennial snow patches, the 29 named glacial features cover about 30.41 square miles (78.8 km2) of the mountain's surface in 2015 and have an estimated volume of about 0.69 cubic miles (2.9 km3).[66][67][29][30]

Glaciers flow under the influence of gravity by the combined action of sliding over the rock on which they lie and by deformation, the gradual displacement between and within individual ice crystals. Maximum speeds occur near the surface and along the centerline of the glacier. During May 1970, Nisqually Glacier was measured moving as fast as 29 inches (74 cm) per day. Flow rates are generally greater in summer than in winter, probably due to the presence of large quantities of meltwater at the glacier base.[30]

The size of glaciers on Mount Rainier has fluctuated significantly in the past. For example, during the last ice age, from about 25,000 to about 15,000 years ago, glaciers covered most of the area now within the boundaries of Mount Rainier National Park and extended to the perimeter of the present Puget Sound Basin.[30]

Between the 14th century and 1850, many of the glaciers on Mount Rainier advanced to their farthest extent downvalley since the last ice age. Many advances of this sort occurred worldwide during this time period known to geologists as the Little Ice Age. During the Little Ice Age, the Nisqually Glacier advanced to a position 650 to 800 ft (200 to 240 m) downvalley from the site of the Glacier Bridge, Tahoma and South Tahoma Glaciers merged at the base of Glacier Island, and the terminus of Emmons Glacier reached within 1.2 mi (1.9 km) of the White River Campground.[30]

Retreat of the Little Ice Age glaciers was slow until about 1920 when retreat became more rapid. The Williwakas Glacier was noted as extinct during the 1930s. Between the height of the Little Ice Age and 1950, Mount Rainier's glaciers lost about one-quarter of their length. Beginning in 1950 and continuing through the early 1980s, however, many of the major glaciers advanced in response to relatively cooler temperatures of the mid-century. The glaciers and snowfields of Mount Rainier also lost volume during this time, except for the Frying Pan and Emmons glaciers on the east flank and the small near-peak snowfields; the greatest volume loss was concentrated from ~1750 m (north) to ~2250 m (south) elevation. The largest single volume loss is from the Carbon Glacier, although it is to the north, due to its huge area at <2000 m elevation.[68] The Carbon, Cowlitz, Emmons, and Nisqually Glaciers advanced during the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of high snowfalls during the 1960s and 1970s.

Since the early-1980s, however, many glaciers have been thinning and retreating and some advances have slowed.[30] In a study using data from 2021, National Park Service scientists removed Stevens Glacier from its inventory of Mount Rainier glaciers due to its dwindling size and lack of evidence that it was moving.[69] Using satellite data in 2022, researchers at Nichols College determined that both Pyramid and Van Trump glaciers had also ceased to exist with only fragments of ice remaining.[69] A significant decline had been noted between 2015 and 2022.[70]

The glaciers on Mount Rainier can generate mudflows through glacial outburst floods not associated with an eruption. The South Tahoma Glacier generated 30 floods in the 1980s and early 1990s, and again in August, 2015.[71]

Human history

At the time of European contact, the river valleys and other areas near the mountain were inhabited by Native Americans who hunted and gathered animals and plants in Mount Rainier's forests and high elevation meadows. Modern descendants of these peoples are represented by members of modern tribes that surround the mountain; including the Nisqually Indian Tribe, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, and the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, among others in the area.[74] The archaeological record of human use of the mountain dates to over 8,500 years before present (BP). Sites related to seasonal use of Mount Rainier and its landscapes are reflected in chipped stone tool remains and settings suggesting functionally varied uses including task-specific sites, rockshelters, travel stops, and long-term base camps. Their distribution on the mountain suggest primary use of subalpine meadows and low alpine habitats that provided relatively high resource abundance during the short summer season.[75] Evidence suggests that there existed a tradition of Native Americans setting fire to areas of the region each year as a way to encourage meadow development.[76]

The first Europeans to reach the Pacific Northwest were the Spanish who arrived by sea in 1774 led by Juan Perez.[77] The next year, under the direction of Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, a boat was sent ashore to Destruction island.[77] Upon landing, the crew was attacked and killed by the local indigenous population.[77] Although attempts were made in 1792 to create a permanent Spanish settlement at Neah Bay, the project was unsuccessful and by 1795, Spain had given up on the region.[77] Although not documented anywhere, it is likely that Spanish sailors first observed Mount Rainier while sailing in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.[77]

Upon reaching what would become California in 1579, Sir Francis Drake claimed the entire northwest coast of North America for England.[77] This claim to the coast of the Pacific Northwest was not further explored until in 1778 Captain James Cook sailed the coastline of modern-day Washington and British Columbia, stimulating a subsequent increase in English ships coming to the area as part of the fur trade.[77] On July 22, 1793, Sir Alexander Mackenzie of the British Northwest Fur Company reached the Pacific Ocean via overland route that crossed the Rocky Mountains.[77]

The first American, John Ledyard, reached the region aboard Captain Cook's ship in 1778.[77] By 1787, six Americans from Boston formed a company which began trading along the northwest coast.[77] The Lewis and Clark overland expedition reached the northwest coast in 1805 and observed Mount Rainier for the first time in the Spring of 1806.[77]

The first documented sighting of Mt. Rainier by a European was by the crew of Captain George Vancouver on 7 May 1792 during the Vancouver Expedition (1790–1795).[77][78][18] On the 8 May 1792, Vancouver gave the name of Mt. Rainier to the observed peak in homage to Vancouver's friend Rear Admiral Peter Rainier.

At the outset of the 19th century, the region where Mt. Rainier was located was claimed by Spain, the U.S., Russia, and Great Britain, with most claims being based on instances of early naval exploration of the region's coast.[77] Spain relinquished all remaining claims to the Pacific Northwest that had not already been handed over with the Louisiana Purchase in 1819 with the purchase and cession of Florida by the United States.[77] In 1824, Russia ceded all land claims south of parallel 54°40′ north to the United States as part of the Russo-American Treaty.[77] In 1818, the United States and the United Kingdom signed a treaty, agreeing upon the joint settlement and occupation of the Oregon country which consisted of the territory north of 42°N latitude, south of 54°40′N latitude, and west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.[77] The 1846 Oregon Treaty between the United States and United Kingdom set new borders between British and American territory along today's approximate borders.[77] In 1853, the land between the Columbia river and the border with British Canada was organized into the Washington Territory, which was the administrative status of the region at the time of the first successful ascent of Mount Rainier.[77]

In 1833, William Fraser Tolmie explored the area looking for medicinal plants. Hazard Stevens and P. B. Van Trump received a hero's welcome in the streets of Olympia after their successful summit climb in 1870.[78][79] The first female ascent was made in 1890 by Fay Fuller, accompanied by Van Trump and three other teammates.[80]

Descending from the summit in 1883, James Longmire discovered a mineral spring; this ultimately led to his establishment of a spa and hotel, drawing other visitors to the area to seek the benefits of the spring.[81] Later, the headquarters of the national park would be established at Longmire, until flooding caused them to be relocated to Ashford.[82] The area also became the site of features like a museum, a post office, and a gas station, with additions like a library and a gift shop soon following; many of these buildings were ultimately nominated to the national historic register of historic places.[82] Longmire remains the second most popular place in the park.[82][83] In 1924, a publication from the park described the area:

"A feature at Longmire Springs of great interest to everyone is the group of mineral springs in the little flat to the west of National Park Inn. There are some forty distinct springs, a half dozen of which are easily reached from the road. An analysis of the waters show that they all contain about the smae [sic] mineral salts but in slightly differing proportions. All the water is highly carbonated and would be classed as extremely "hard". Certain springs contain larger amounts of soda, iron and sulphur, giving them a distinct taste and color."[84]

John Muir climbed Mount Rainier in 1888, and although he enjoyed the view, he conceded that it was best appreciated from below. Muir was one of many who advocated protecting the mountain. In 1893, the area was set aside as part of the Pacific Forest Reserve in order to protect its physical and economic resources, primarily timber and watersheds.[85]

Citing the need to also protect scenery and provide for public enjoyment, railroads and local businesses urged the creation of a national park in hopes of increased tourism. On March 2, 1899, President William McKinley established Mount Rainier National Park as America's fifth national park. Congress dedicated the new park "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people"[86] and "... for the preservation from injury or spoliation of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition."[87]

On 24 June 1947, Kenneth Arnold reported seeing a formation of nine unidentified flying objects over Mount Rainier. His description led to the term "flying saucers".[88]

In 1998, the United States Geological Survey began putting together the Mount Rainier Volcano Lahar Warning System to assist in the emergency evacuation of the Puyallup River valley in the event of a catastrophic debris flow. It is now run by the Pierce County Department of Emergency Management. Tacoma, at the mouth of the Puyallup, is only 37 mi (60 km) west of Rainier, and moderately sized towns such as Puyallup and Orting are only 27 and 20 mi (43 and 32 km) away, respectively.[89]

Mount Rainier appears on four distinct United States postage stamp issues. In 1934, it was the 3-cent issue in a series of National Park stamps, and was also shown on a souvenir sheet issued for a philatelic convention. The following year, in 1935, both of these were reprinted by Postmaster General James A. Farley as special issues given to officials and friends. Because of complaints by the public, "Farley's Follies" were reproduced in large numbers. The second stamp issue is easy to tell from the original because it is imperforate. Both stamps and souvenir sheets are widely available.[90]

The Washington state quarter, which was released on April 11, 2007, features Mount Rainier and a salmon.[91][92]

Climbing

Mountain climbing on Mount Rainier is difficult, involving traversing the largest glaciers in the U.S. south of Alaska. Most climbers require two to three days to reach the summit, with a success rate of approximately 50%, with weather and physical conditioning of the climbers being the most common reasons for failure. About 8,000 to 13,000 people attempt the climb each year,[93] about 90% via routes from Camp Muir on the southeast flank,[94] and most of the rest ascend Emmons Glacier via Camp Schurman on the northeast. Climbing teams require experience in glacier travel, self-rescue, and wilderness travel. All climbers who plan to climb above the high camps, Camp Muir and Camp Schurman, are required to purchase a Mount Rainier Climbing Pass and register for their climb.[95] Additionally, solo climbers must fill out a solo climbing request form and receive written permission from the park superintendent before attempting to climb.[96]

Climbing routes

All climbing routes on Mount Rainier require climbers to possess some level of technical climbing skill. This includes ascending and descending the mountain with the use of technical climbing equipment such as crampons, ice axes, harnesses, and ropes. Difficulty and technical challenge of climbing Mount Rainier can vary widely between climbing routes. Routes are graded in NCCS Alpine Climbing format.

The normal route to the summit of Mount Rainier is the Disappointment Cleaver Route, YDS grade II-III. As climbers on this route have access to the permanently established Camp Muir, it sees the significant majority of climbing traffic on the mountain. This route is also the most common commercially guided route. The term "cleaver" is used in the context of a rock ridge that separates two glaciers. The reason for naming this cleaver a "disappointment" is unrecorded, but it is thought to be due to climbers reaching it only to recognize their inability to reach the summit.[97] An alternative route to the Disappointment Cleaver is the Ingraham Glacier Direct Route, grade II, and is often used when the Disappointment Cleaver route cannot be climbed due to poor route conditions.

The Emmons Glacier Route, grade II, is an alternative to the Disappointment Cleaver route and poses a lower technical challenge to climbers. The climbers on the route can make use of Camp Schurman (9,500 ft), a glacial camp site. Camp Schurman is equipped with a solar toilet and a ranger hut.[98]

The Liberty Ridge Route, grade IV, is a considerably more challenging and objectively dangerous route than the normal route to the summit. It runs up the center of the North Face of Mount Rainier and crosses the very active Carbon Glacier. First climbed by Ome Daiber, Arnie Campbell and Jim Burrow in 1935, it is listed as one of the Fifty Classic Climbs of North America by Steve Roper and Allen Steck. This route only accounts for approximately 2% of climbers on the mountain, but approximately 25% of its deaths.[99]

Dangers and accidents

About two mountaineering deaths each year occur because of rock and ice fall, avalanche, falls, and hypothermia. These incidents are often associated with exposure to very high altitude, fatigue, dehydration, and/or poor weather.[100] 58 deaths on Mount Rainier have been reported from 1981 to 2010. Approximately 7 percent of mountaineering deaths and 6 percent of mountaineering accidents in the United States are attributed to Mount Rainier.[11]

The first known climbing death on Mount Rainier was Edgar McClure, a professor of chemistry at the University of Oregon, on July 27, 1897. During the descent in darkness, McClure stepped over the edge of the rock and slid to his death on a rocky outcrop. The spot is now known as McClure Rock.[101]

Willi Unsoeld, who reached the summit of Mount Everest in 1963, was killed, along with an Evergreen State College student, in an avalanche on Mount Rainier in 1979. He had climbed the mountain over 200 times.

The worst mountaineering accident on Mount Rainier occurred in 1981, when ten clients and a guide died in an avalanche/ice fall on the Ingraham Glacier.[102] This was the largest number of fatalities on Mount Rainier in a single incident since 32 people were killed in a 1946 plane crash on the South Tahoma Glacier.[103]

In one of the worst disasters on the mountain in over thirty years, six climbers—two guides, and four clients—were killed on May 31, 2014, after the climbers fell 3,300 feet (1,000 m) while attempting the summit via the Liberty Ridge climbing route. Low-flying search helicopters pinged the signals from the avalanche beacons worn by the climbers, and officials concluded that there was no possible chance of survival. Searchers found tents and clothes along with rock and ice strewn across a debris field on the Carbon Glacier at 9,500 ft (2,900 m), possible evidence for a slide or avalanche in the vicinity where the team went missing, though the exact cause of the accident is unknown.[104] The bodies of three of the client climbers were spotted on August 7, 2014, during a training flight and subsequently recovered on August 19, 2014. The bodies of the fourth client climber and two guides were never found.[105][106]

Outdoor recreation

In addition to climbing, hiking, backcountry skiing, photography, and camping are popular activities in the park. Hiking trails, including the Wonderland Trail—a 93-mile (150 km) circumnavigation of the peak, provide access to the backcountry. Popular for winter sports include snowshoeing and cross-country skiing.[107]

Climate

The summit of Mount Rainier has an ice cap climate (Köppen climate classification: EF)

| Climate data for Mount Rainier Summit, 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 9.2 (−12.7) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

9.1 (−12.7) |

12.9 (−10.6) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

38.2 (3.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

34.0 (1.1) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

8.2 (−13.2) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 3.1 (−16.1) |

0.9 (−17.3) |

0.7 (−17.4) |

3.4 (−15.9) |

11.2 (−11.6) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

6.1 (−14.4) |

2.4 (−16.4) |

11.2 (−11.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −3.0 (−19.4) |

−6.5 (−21.4) |

−7.8 (−22.1) |

−6.1 (−21.2) |

0.7 (−17.4) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

13.2 (−10.4) |

13.9 (−10.1) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

5.1 (−14.9) |

−0.4 (−18.0) |

−3.4 (−19.7) |

1.9 (−16.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 14.09 (358) |

11.49 (292) |

11.38 (289) |

6.73 (171) |

3.62 (92) |

3.08 (78) |

1.13 (29) |

1.30 (33) |

3.01 (76) |

7.61 (193) |

12.89 (327) |

13.60 (345) |

89.93 (2,284) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | −4.8 (−20.4) |

−8.7 (−22.6) |

−9.0 (−22.8) |

−7.6 (−22.0) |

−2.0 (−18.9) |

3.4 (−15.9) |

8.1 (−13.3) |

7.9 (−13.4) |

5.3 (−14.8) |

1.8 (−16.8) |

−4.0 (−20.0) |

−6.0 (−21.1) |

−1.3 (−18.5) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[108] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Camp Muir, Washington (10,110 ft), (2014–2022 normals and extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 47.9 (8.8) |

48.5 (9.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

60.1 (15.6) |

53.9 (12.2) |

66.5 (19.2) |

66.8 (19.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

64.3 (17.9) |

57.0 (13.9) |

51.3 (10.7) |

47.7 (8.7) |

68.6 (20.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 23.2 (−4.9) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

35.1 (1.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

48.0 (8.9) |

50.0 (10.0) |

42.1 (5.6) |

34.8 (1.6) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

32.7 (0.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 17.7 (−7.9) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

20.0 (−6.7) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

34.8 (1.6) |

42.8 (6.0) |

44.4 (6.9) |

36.7 (2.6) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

15.1 (−9.4) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 12.6 (−10.8) |

9.0 (−12.8) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

14.3 (−9.8) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

38.5 (3.6) |

39.7 (4.3) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

14.8 (−9.6) |

9.5 (−12.5) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11.2 (−24.0) |

−11.6 (−24.2) |

−4.3 (−20.2) |

−6.2 (−21.2) |

0.7 (−17.4) |

4.0 (−15.6) |

19.3 (−7.1) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

7.4 (−13.7) |

0.5 (−17.5) |

−3.8 (−19.9) |

−14.4 (−25.8) |

−14.4 (−25.8) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.2 | 69.7 | 69.3 | 63.5 | 63.2 | 54.4 | 42.5 | 43.0 | 54.2 | 62.3 | 71.5 | 72.5 | 61.5 |

| Source: NWAC[109] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Mount Rainier's protected status as a national park protects its primeval Cascade ecosystem, providing a stable habitat for many species in the region, including endemic flora and fauna that are unique to the area, such as the Cascade red fox and Mount Rainier lousewort.[110][111][112] The ecosystem on the mountain is very diverse, owing to the climate found at different elevations.[113] Scientists track the distinct species found in the forest zone, the subalpine zone, and the alpine zone.[114] They have discovered more than one thousand species of plants and fungi.[114] The mountain is also home to 65 species of mammals, 5 reptiles, 182 birds, 14 amphibians, and 14 species of native fish, in addition to an innumerable amount of invertebrates.[113]

Flora

.jpg.webp)

Mount Rainier has regularly been described as one of the best places in the world to view wildflowers.[115][116] In the subalpine region of the mountain, the snow often stays on the ground until summer begins, limiting plants to a much shorter growing season. This produces dramatic blooms in areas like Paradise.[114][117] In 1924, the flowers were described by naturalist Floyd W. Schmoe:

"Mount Rainier National Park is perhaps better known the world over for these wonderful flowers than for any one feature. The mountains, the glaciers, the cascading streams and the forests may be equalled if one looks far away enough, but no park has been so favored in the way of wild flowers."[118]

Forests on the mountain span from as young as 100 years old to sections of old growth forest that are calculated to be 1000 years or more in age.[114] The lower elevation consists mainly of western red-cedar, Douglas fir, and western hemlock.[114] Pacific silver fir, western white pine, Alaska yellow cedar, and noble fir are found further up the mountain. In the alpine level, Alaskan yellow cedar, subalpine fir, and mountain hemlock grow.[114]

Fauna

.jpg.webp)

The mountain supports a wide variety of animal life, including several species that are protected on the state or federal level, like the Northern Spotted Owl.[113] Efforts are also being made to reintroduce native species that had locally been hunted to extinction, like the Pacific fisher.[113] There are sixty-five types of mammals living on the mountain, including cougars, mountain goats, marmots, and elk. Common reptiles and amphibians include garter snakes, frogs, and salamanders. There are many types of birds found throughout the different elevations on the mountain, but while some live there all year, many are migratory. Salmon and trout species use the rivers formed by the glaciers, and though the lakes stopped being stocked in 1972, thirty lakes still have reproducing populations.[119]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Mount Rainier, Washington". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Topographic map of Mount Rainier". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier, Washington". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ↑ Egan, Timothy (August 22, 1999). "Respecting Mount Rainier". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ↑ Hill, Craig (November 16, 2006). "Taking the measure of a mountain". The News Tribune. pp. E1, E4. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Signani, Larry (19 July 2000). "The Height of Accuracy". Point of Beginning. BNP Media. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ↑ "USA Lower 48 Top 100 Peaks by Prominence". Peakbagger.com.

- ↑ "Decade Volcanoes". CVO. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2012-06-03.

- 1 2 Driedger, C.L.; Scott, K.M. (2005-03-01). "Mount Rainier – Learning to Live with Volcanic Risk". Fact Sheet 034-02. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- 1 2 3 Emma P. DeLoughery; Thomas G. DeLoughery (14 June 2022). "Review and Analysis of Mountaineering Accidents in the United States from 1947–2018". High Altitude Medicine & Biology. 23 (2): 114–18. doi:10.1089/ham.2021.0085. PMID 35263173. S2CID 247361980. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ↑ "Annual Climbing Statistics". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Puget Sound Geographical names". Tulalip Tribes of Washington. January 16, 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 469. ISBN 080613576X.

- ↑ Longoria, Ruth (September 26, 1999). "Puget hits the shore". The Olympian. p. A12. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Beavert, Virginia (2009), Ichishkiin sinwit : Yakama/Yakima Sahaptin dictionary, Heritage University, ISBN 978-0-295-98915-0, OCLC 1299328956, retrieved 2023-01-31

- ↑ "Is it time to rename Mount Rainier to its former native name?". Archived from the original on 2014-10-21.

- 1 2 "Historical Notes: Vancouver's Voyage". Mount Rainier Nature Notes. VII (14). 1929. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2015-02-03.

- ↑ Catton, Theodore (2006). National Park, City Playground: Mount Rainier in the Twentieth Century. A Samuel and Althea Stroum Book. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0295986433.

- ↑ Winthrop, Theodore (1866). "VII. Tacoma". The canoe and the saddle : adventures among the northwestern rivers and forests, and Isthmiana (8th ed.). Boston: Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 0665377622. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ Orth, Donald J. (1992). "The Creation" (PDF). Meridian. Map and Geospatial Information Round Table (2): 18. OCLC 18508074. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ Blethen, C. B. (February 3, 1924). "Academic Dispute Flares Forth; Mount Rainier's Name at Issue". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ "The Outdoor World: Mt. Rainier's Name Stands". Recreation. Vol. LVII, no. 3. Outdoor World Publishing Company. September 1917. p. 142. OCLC 12010285. Retrieved August 31, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Seattle Times editorial board (2015-09-01). "After McKinley, it's time to consider renaming Rainier". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier". Peakbagger.com.

- ↑ "World Top 50 by Prominence". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Bruce Barcott (1999-04-27). "The Mountain is Out". Western Washington University. Archived from the original on 2009-01-13. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ "View of Rainier". Nature Spot. Archived from the original on 2009-11-03. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- 1 2 Topinka, Lyn (2002). "Mount Rainier Glaciers and Glaciations". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

This article incorporates public domain material from Driedger, C.L. Glaciers on Mount Rainier. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-04-21. (Open-File Report 92-474).

This article incorporates public domain material from Driedger, C.L. Glaciers on Mount Rainier. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-04-21. (Open-File Report 92-474). - ↑ Zimbelman, D.R.; Rye, R.O.; Landis, G.P. (2000). "Fumaroles in ice caves on the summit of Mount Rainier: Preliminary stable isotope, gas, and geochemical studies". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 97 (1–4): 457–73. Bibcode:2000JVGR...97..457Z. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00180-8. Archived from the original on 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ↑ Sandi Doughton (2007-10-25). "Exploring Rainier's summit steam caves". The News Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ Kiver, Eugene P.; Mumma, Martin D. (1971). "Summit Firn Caves, Mount Rainier, Washington". Science. 173 (3994): 320–22. Bibcode:1971Sci...173..320K. doi:10.1126/science.173.3994.320. PMID 17809214. S2CID 21323576.

- ↑ Kiver, Eugene P.; Steele, William K. (1975). "Firn Caves in the Volcanic Craters of Mount Rainier, Washington". The NSS Bulletin. 37 (3): 45–55. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Named after Bailey Willis, USGS geological engineer, who played a key role in getting Mount Rainier designated as a national park. "Scientific Exploration Of Mount Rainier". Mount Rainier: Its Human History Associations. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-03-26. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- ↑ John Roper; Jeff Howbert. "Washington 100 Highest Peaks with 400 feet of prominence". The Northwest Peakbaggers Asylum. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ "Little Tahoma Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "Little Tahoma". Mount Rainier National Park. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- 1 2 Wood, C.A.; Kienle, J. (1990). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0521364698.

- ↑ Sisson, T.W. (1995). History and Hazards of Mount Rainier, Washington. United States Geological Survey. Open-File Report 95-642.

- ↑ Scott, Kevin M.; Vallance, James W. (1993). "History of landslides and Debris Flows at Mount Rainier". Open-File Report 93-111. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- 1 2 Parchman, F. (2005-10-19). "The Super Flood". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on 2007-03-21. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- 1 2 Crandall, D.R. (1971). "Postglacial Lahars From Mount Rainier Volcano, Washington". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 677. doi:10.3133/pp677. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ "SoilWeb: An Online Soil Survey Browser | California Soil Resource Lab". Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L. (2005). "Mount Rainier: America's Most Dangerous Volcano". Fire Mountains of the West (3rd ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 299–334. ISBN 087842511X.

- ↑ "Rainier". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier Volcano". United States Geological Survey. 2007-04-27. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian (2003-09-25). "Rainier Eruption Odds Low, Impact High, Expert Says". National Geographic Ultimate Explorer. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ↑ Klemetti, Erik (2015-05-22). "Why Have Volcanoes in the Cascades Been So Quiet Lately?". Wired. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Scientists eye Cascade range volcanoes". 2014-02-21. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "Mount Mazama and Crater Lake: Growth and Destruction of a Cascades Volcano". pubs.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ McNichols, Joshua. "What will happen when Mount Rainier erupts?". KUOW. Archived from the original on 2016-07-16. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

Statistics show there's a volcanic eruption in the Cascades two to three times every century; Mount Rainier is the tallest mountain in that range.

- ↑ Malone, S.D.; Moran, S.C. (1995). "Mount Rainier, Washington, USA – IAVCEI "Decade Volcano" – Hazards, Seismicity, and Geophysical Studies". IAVCEI conference on volcanic hazard in densely populated regions. Archived from the original on 1997-07-22.

- ↑ Tucker, Rob (2001-07-23). "Lahar: Thousands live in harm's way". Tacoma News Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-03-17.

- ↑ Scott, K.M.; Vallance, J.W.; Pringle, P.T. (1995). "Sedimentology, Behavior, and Hazards of Debris Flows at Mount Rainier, Washington". Geological Survey Professional Paper. Professional Paper. United States Geological Survey (1547). doi:10.3133/pp1547. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- 1 2 Hoblitt, R.P.; J.S. Walder; C.L. Driedger; K.M. Scott; P.T. Pringle; J.W. Vallance (1998). "Volcano Hazards from Mount Rainier, Washington, Revised". Open-File Report 98-428. United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr98428. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ↑ Scott, Kevin M.; Vallance, J. W. (1995). Mount Rainier Debris-Flow Maps available from USGS (Report). United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ha729. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ↑ "Monitoring Lahars at Mount Rainier | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-10-08. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ↑ "Volcanic Hazard Areas" (PDF). Critical Areas, Stormwater, and Clearing and Grading Ordinances. King County, Washington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-05. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ↑ "Nevado del Ruiz". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ "Paths of Destruction: The Hidden Threat at Mount Rainier". Geotimes. April 2004. Archived from the original on 2013-12-29. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- ↑ The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (2006-12-07). "Mount Rainier Seismicity Information". Archived from the original on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Cascades Volcano Observatory (2006-09-23). "Mount Rainier Swarm Report". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2012-01-17. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ "Spate of quakes around Mount Rainier". The Seattle Times. 2011-10-17. Archived from the original on 2011-10-20.

- ↑ "Swarm of earthquakes detected at Mount Rainier". MyNorthwest.com. 2021-02-21. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-03-02.

- ↑ "Abstract: Dramatic Changes to Glacial Volume and Extent Sine the Late 19th Century at Mount Rainer National Park, Washington, USA (GSA Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington, USA – 2017)". gsa.confex.com. Archived from the original on 2018-06-02. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ↑ Beason, Scott (2017). "Change in glacial extent at Mount Rainier National Park from 1896 to 2015". National Resource Report 2017/1472. NPS. Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- ↑ Sisson, T.W.; Robinson, J.E.; Swinney, D.D. (July 2011). "Whole-edifice ice volume change A.D. 1970 to 2007/2008 at Mount Rainier, Washington, based on LiDAR surveying". Geology. 39 (7): 639–642. Bibcode:2011Geo....39..639S. doi:10.1130/G31902.1. ISSN 1943-2682.

- 1 2 Sengupta, Somini (2023-09-12). "The 'Forever' Glaciers of America's West Aren't Forever Anymore". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-09-16.

- ↑ Bush, Evan (June 22, 2023). "Three of Mount Rainier's glaciers have melted away". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 22, 2023. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ↑ Doughton, Sandi (2015-08-14). "Rainier melting unleashes 'glacial outbursts' of debris". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2015-08-20. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ Winsey, H. J. (1888). The Great Northwest. St Paul, MN: Northern News Co. frontispiece.

- ↑ "Mowich" is the Chinook Jargon word for "deer".

- ↑ "Archaeology". Mount Rainier National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Burtchard, Greg C. (2007). "Holocene Subsistence and Settlement Patterns: Mount Rainier and the Montane Pacific Northwest" (PDF). Archaeology in Washington. 13: 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Catton, Theodore (1996). Wonderland : an administrative history of Mount Rainier National Park. National Park Service. OCLC 45308935.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Rensch, Hero Eugene (1935). Mount Rainier, its human history associations. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Field Division of Education. OCLC 1042816617.

- 1 2 Haines, Aubrey L. (1999) [1962]. Mountain fever : historic conquests of Rainier. Original publisher: Oregon Historical Society; Republished by University of Washington. ISBN 0295978473.

- ↑ "Hazard Stevens photographs, c. 1840s–1918". University of Oregon Libraries Historic Photograph Collections. University of Oregon. March 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ↑ Bragg, Lynn (2010). More than Petticoats: Remarkable Washington Women (2nd ed.). Globe Pequot.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier History". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Longmire: Designing a National Park Style". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ McIntyre, Robert N. "Short History of Mount Rainier National Park" (PDF). NPS History. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Schmoe, F.W. (1 July 1924). "Mineral Springs at Longmire". Nature Notes. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ "John Muir and Mount Rainier". Arthur Churchill Warner Photographs. 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-11-27. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ↑ "U.S. Code: Title 16 Chapter 1 Subchapter XI § 91". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ↑ "U.S. Code: Title 16 Chapter 1 Subchapter XI § 92". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ↑ "Kenneth Arnold". history.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- ↑ Driedger, C.L.; Scott, W.E. (2008). "Mount Rainier – Living Safely With a Volcano in Your Backyard". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- ↑ "US Stamps – Commemoratives of 1934–1935". stamp-collecting-world.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Washington State Quarter". Washington State Arts Commission. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Green, Sara Jean (2007-04-12). "Washington quarter makes debut". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- ↑ "MORA Climbing Statistics". National Park Service. 2005-07-30. Archived from the original on 2006-01-01.

- ↑ "Camp Muir, Mount Rainier, Washington". University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ "Mt. Rainier Climbing Pass FAQs". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ↑ "Climbing Mount Rainier" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-08. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ↑ "Disappointment Cleaver-Ingraham Glacier" (PDF). National Park Service. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ↑ "Things to Know Before You Climb". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ "Liberty Ridge is risky, deadly Mount Rainier route". The Seattle Times. 2 June 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ Litch, Jim (2017). "Health". In Gautier, M (ed.). Mount Rainier: A Climbers Guide. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1594858420.

- ↑ Haines, Aubrey (1999). Mountain fever: historic conquests of Rainier. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 0295978473. OCLC 41619403.

- ↑ Hatcher, Candy (2000-03-30). "Ghosts of Rainier: Icefall in 1981 entombed 11 climbers". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ "HistoryLink: A Curtis Commando R5C transport plane crashes into Mount Rainier, killing 32 U.S. Marines, on December 10, 1946". HistoryLink.org. 2006-07-29. Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ "6 climbers dead on Mount Rainier". The Seattle Times. June 2, 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-12-25. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ↑ John de Leon (2014-08-20). "Bodies of 3 missing climbers recovered from Mount Rainier". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ Paige Cornwell (2014-08-22). "Bodies of 3 Mount Rainier climbers identified". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ "Backcountry Skiing Guide to Mount Rainier, Washington". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". prism.oregonstate.edu. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ↑ "Weather Data Area Page – Mt Rainier". Northwest Weather and Avalanche Center. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Mount Rainier is a Special Place". U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "Carnivores". Mount Rainier National Park. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Warren, F. A.; Pennell. "Pedicularis rainierensis" (PDF). Department of Natural Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Animals". Mount Rainier National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Plants". Mount Rainier National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Blackburn, Dan (March 22, 2015). "Mt. Rainier National Park readies for a wildflower spectacle". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Gibbons, Bob (2011). Wildflower Wonders: The 50 Best Wildflower Sites in the World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691152295.

- ↑ "Paradise". Mount Rainier National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Schmoe, F. W. (9 July 1924). "Flower Conditions". Nature Notes. 2 (4). Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ "Fish". Mount Rainier National Park. U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

Notes

- ↑ Pronounced tuh-KWOH-buh

External links

- Mount Rainier National Park (also used as a reference)

- "Mount Rainier Volcano Lahar Warning System". Volcano Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- Mt. Rainier Eruption Task Force (pdf)

- Mount Rainier stream drainage

- Mount Rainier Trail Descriptions

- "Mount Rainier". SummitPost.org. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- Mount Rainier National Park at Curlie

- Doughton, Sandi (2014-09-26), "Under Rainier's crater, a natural laboratory like no other", The Seattle Times: contains images and videos of the summit caves

University of Washington libraries and digital collections

- Lawrence Denny Lindsley Photographs, Landscape and nature photography of Lawrence Denny Lindsley, including photographs of scenes around Mount Rainier.

- The Mountaineers Collection, Photographic albums and text documenting the Mountaineers official annual outings undertaken by club members from 1907 to 1951, includes 3 Mt. Rainier albums (ca. 1912, 1919, 1924).

- Henry M. Sarvant Photographs, photographs by Henry Mason Sarvant depicting his climbing expeditions to Mt. Rainier and scenes of the vicinity from 1892 to 1912.

- Alvin H. Waite Photographs Photographs of Mt. Rainier by Alvin H. Waite, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.