| Lifeboat id numbers on deck | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ←bow | stern→ | ||

| (01) (03) (05) (07) | (09) (11) (13) (15) | ||

| (A) \(C) | |||

| (B) /(D) | |||

| (02) (04) (06) (08) | (10) (12) (14) (16) | ||

| Lifeboats 7, 5, 3 & 8 left first. Collapsible lifeboats A, B, C & D were stored inboard. Boat A floated off the deck, and Boat B floated away upside down. | |||

Lifeboats played a crucial role during the sinking of the Titanic on 14–15 April 1912. The ship had 20 lifeboats that, in total, could accommodate 1,178 people, a little over half of the 2,209 on board the night it sank.

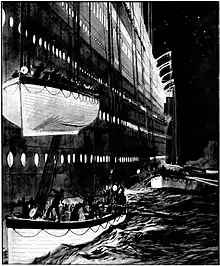

18 lifeboats were used, loading between 11:45 P.M. and 2:05 A.M., though Collapsible Boat A floated off the ship's partially submerged deck and Collapsible Boat B floated away upside down minutes before the ship upended and sank.

Many lifeboats only carried a fraction of their maximum capacity; there are many versions as to the reasoning behind half-filled lifeboats. Some sources claimed they were afraid of the lifeboat buckling under the weight; others suggested it was because the crew was following orders to evacuate women and children first. As the half-filled boats rowed away from the ship, they were too far away for other passengers to reach, and most lifeboats did not return to the wreck due to a fear of being swamped by drowning victims or the suction of the ship sinking. Only Lifeboats 3 and 15 returned to retrieve survivors from the water.

The closest ship to respond to the Titanic's distress signals, the RMS Carpathia, did not reach the lifeboats until 4 A.M., one hour and forty minutes after the Titanic sank. According to generally accepted reports, the rescue continued until the last lifeboat was collected at 8:30 A.M.

Although the number of lifeboats was insufficient, Titanic was in compliance with maritime safety regulations at the time. The sinking showed that the regulations were outdated for such large passenger ships. The inquiry also revealed that White Star Line wanted fewer lifeboats on the decks to provide unobstructed views for passengers and to give the ship more aesthetic appeal when seen from an exterior viewpoint. In the event of an emergency, it was not anticipated that all passengers and crew would require evacuation at the same time; it was believed that Titanic could float long enough to allow a transfer of passengers and crew to a rescue vessel.

Compounding the disaster, Titanic's crew was poorly trained on using the davits (lifeboat launching equipment). As a result, lifeboat launches were slow, improperly executed, and poorly supervised. These factors contributed to the lifeboats leaving with only half their capacity.

A total of 1,503 people did not make it onto a lifeboat and were aboard Titanic when she sank in the North Atlantic Ocean, and 705 people remained in the lifeboats until later that morning, when they were rescued by the RMS Carpathia. Those aboard the lifeboats were picked up by Carpathia over the course of 4 hours and 30 minutes, from about 4 A.M. to 8:30 A.M., and 13 of the lifeboats were also taken aboard. The lifeboats were returned to the White Star Line at New York Harbor, as they were the only items of value salvaged from the shipwreck, but subsequently vanished from history over time.

Number and types of lifeboats

Titanic had 20 lifeboats of three different types:

- 14 clinker-built wooden lifeboats, measuring 30 feet (9.1 m) long by 9 feet 1 inch (2.77 m) wide by 4 feet (1.2 m) deep. Each had a capacity of 655.2 cubic feet (18.55 m3) and was designed to carry 65 people. The rudders were made of elm – selected because it resisted splitting – and were 1.75 inches (4.4 cm) thick. The exteriors of the boats were fitted with "grablines" for people in the water to hold on to.[2][3] They were fitted with a variety of equipment to aid the occupants, comprising 10 oars, a sea anchor, two bailers, a painter (effectively a tow-rope) 150 feet (46 m) long, two boat-hooks, two 10 imperial gallons (45 L) tanks of fresh water, a mast and sail, a compass, a lantern and watertight metal provision tanks which contained biscuits.[4] This equipment was not kept in the boats for fear of theft, but in locked boxes on the deck. In many cases, the equipment was not transferred to the boats when they were launched on 15 April and ended up going down with the ship.[3] Blankets and a spare lifebelt could also be found in the boats. Apparently unknown to many officers and crew, these boats were reinforced with steel beams in their keels to prevent buckling in the davits under a full load.

- 2 wooden cutters intended to be used as emergency boats. They were kept ready to be launched quickly in the event of an incident requiring a boat in the water, such as a man overboard. The cutters were swung out at all times when the ship was underway, uncovered and with all their equipment, including a lighted oil lantern placed in the boat every evening. The cutters were of a similar design to the main lifeboats, but smaller, measuring 25 feet 2 inches (7.67 m) long by about 7 feet (2.1 m) wide by 3 feet (0.91 m) deep. They had a capacity of 322 cubic feet (9.1 m3) and could carry 40 people.[5] They were equipped similarly to the main lifeboats but with only one boathook, one water container, one bailer and six oars each.[6]

- 4 "collapsible" Engelhardt lifeboats. These were effectively boat-shaped unsinkable rafts of kapok and cork, with heavy canvas sides that could be raised to form a boat. They measured 27 feet 5 inches (8.36 m) long by 8 feet (2.4 m) wide by 3 feet (0.91 m) deep. Their capacity was 376.6 cubic feet (10.66 m3) and each could carry 47 people.[5] The Engelhardts, built to a Danish design,[7] were built by the boatbuilders McAlister & Son of Dumbarton, Scotland.[8] Their equipment was similar to that of the cutters, but they had no mast or sail, had eight oars apiece and were steered using a steering oar rather than a rudder.[6]

The main lifeboats and cutters were built by Harland and Wolff at Queen's Island, Belfast, at the same time that Titanic and her sister ship Olympic were constructed. They were designed for maximum seaworthiness, with a double-ended design (effectively having two bows). This reduced the risk that they would be flooded by a following sea (i.e., having waves breaking over the stern). If a lifeboat had to be beached, the design would also resist the incoming surf. Another safety feature consisted of airtight copper tanks within the boats' sides to provide extra buoyancy.[2]

Use and locations aboard Titanic

All but two lifeboats were situated on the Boat Deck, the highest deck of Titanic. They were located on wooden chocks at the fore and aft parts of the Boat Deck, on both sides of the ship; two groups of three at the forward end, and two groups of four at the aft end.[9] The two cutters were situated immediately aft of the bridge, one to port and the other to starboard.[10] While Titanic was at sea, they were positioned outboard so that they could be lowered instantly in the event of an emergency, such as needing to rescue a person who had fallen overboard.[7] The lifeboats were assigned odd numbers on the starboard side and even numbers on the port side, running from forward to aft, while the collapsible lifeboats were lettered A to D.[9]

The collapsibles were stored in two places. Two of them were stowed on the deck in their collapsed state underneath the cutters, while the remaining two were situated on top of the officers' quarters. Despite the first two both being erected and launched without difficulty during Titanic's sinking, the other two both turned out to be very poorly located. They were both located 8 feet (2.4 m) off the deck and lowering them required a piece of equipment held in the boatswain's store in the bow. By the time this was realised, the bow was already well underwater, and the store was inaccessible. They were manhandled down and floated away freely as the deck flooded.[4]

The lifeboats were intended to be launched from davits supplied by the Welin Davit & Engineering Company of London. All lifeboats but the collapsibles were slung from the davits, ready to be launched.[6] The davits were of a highly efficient double-acting quadrant design, capable of being slung inboard (hanging over the deck) as well as outboard (hanging over the side) to pick up additional lifeboats.[5] The davits aboard Titanic were capable of accommodating 64 lifeboats, though only 16 were actually fitted to them. The collapsibles were also intended to be launched via the davits.[10] Each davit was doubled up, supporting the forward arm of one boat and the after arm of the next one along. A bitt and sheave was located at the keel of each davit to facilitate the lowering of boats, and the falls could be taken across the deck so that a number of men could work simultaneously on each boat and davit.[9] They had to be lowered by hand, ideally by a team of between eight and ten men. Despite Titanic having a number of electric winches, they could only have been used to winch the lifeboats back out of the water.[11]

Lack of lifeboats and training

Titanic only had enough lifeboats to accommodate approximately a third of the ship's total capacity. Had every lifeboat been filled accordingly, they still could have only evacuated about 53 per cent of those actually on board on the night of the sinking.[11] The shortage of lifeboats was not due to the lack of space; Titanic had actually been designed to accommodate up to 64 lifeboats[5] – nor was it because of cost, as the price of an extra 32 lifeboats (when it could have even held an extra 48) would only have been some $16,000, a tiny fraction of the $7.5 million that the company had spent on Titanic.[12] The reason lay in a combination of outdated safety regulations and complacency by the White Star Line, Titanic's operators.[13]

In 1886, a committee of the British Board of Trade devised safety regulations for the merchant vessels of the time. These were updated with the passage of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894 and were modified subsequently, but by 1912 they had a fatal flaw– they had been intended to regulate vessels of up to 10,000 tons.[4] At the time of the original regulations in the 1880s the largest liners (the Cunard sisterships Etruria and Umbria) had a registered tonnage of just under 8000grt. The 1894 Act made provision for vessels with a registered tonnage "greater than 10,000 tons" but at the time the legislation was drafted the largest liner in service was then Cunard's Campania of 12,950grt and with a maximum capacity of 2,500 passengers and crew. Between 1895 and 1910 the size and capacity of new liners entering service rapidly exceeded the scope of the Act -Titanic had a gross register tonnage of 46,328 tons and a total capacity of over 3,300 people.[14] Other ships were in a similar situation; 33 of the 39 British liners over 10,000 tons did not have enough lifeboats for all aboard (the six that did were marginally over 10,000 tons). RMS Carmania was perhaps the worst of them, with only enough lifeboats for 29 per cent of her occupants. Foreign ships, such as the German liner SS Amerika and SS St. Louis similarly had only enough lifeboat space for about 54–55 per cent of those aboard. A random sampling of ships that exceeded 10,000 tons in 1912, of numerous different shipping lines in the United States, Canada, and Europe, show the ship that came the closest to carrying enough lifeboats for all its passengers was the French Line's La Province which carried enough boats to accommodate 82 per cent of her passenger capacity. Walter Lord stated in his 1987 book The Night Lives On that the lack of lifeboats on the Olympic-class liners might have had more to do with economics than one might have thought. Had Olympic and Titanic been properly provisioned with enough lifeboats, it might have drawn notice by the press that other smaller and perhaps less safely equipped liners were lacking sufficient lifeboats. This could have created a domino effect, leading to a call for more stringent regulations concerning lifesaving equipment on board ships, circumstances which would have cost numerous shipping lines a considerable amount of money to accommodate.[15]

The regulations required a vessel of 10,000 tons or more to carry 16 lifeboats with a total capacity of 9,625 cubic feet (272.5 m3), sufficient for 960 people. Titanic actually carried four more lifeboats than was needed under the regulations. Her total lifeboat capacity was 11,327.9 cubic feet (320.77 m3),[8] which was theoretically capable of taking 1,178 people.[5] The regulations required that lifeboats should measure between 16–30 feet (4.9–9.1 m), with a minimum capacity of 125 cubic feet (3.5 m3) each. The cubic capacity divided by ten indicated the approximate number of people that could be carried safely in each lifeboat, and also dictated the size of the airtight buoyancy tanks incorporated into the boats' hulls, with each person corresponding to 1 cubic foot (0.028 m3) of tank capacity.[2]

In reality, the given capacity was quite nominal, as filling the lifeboats to their indicated capacity would have required some passengers to stand. This did in fact happen to some of the last lifeboats to leave Titanic; at the subsequent British enquiry, Titanic's Second Officer Charles Lightoller testified that the nominal capacity could only have applied "in absolutely smooth water, under the most favourable conditions." The proper capacity would have been more like 40 people per boat under typical conditions.[16] Few officers and crew were aware that steel beam reinforcements had been added to the keels of the boats to prevent buckling in the davits under a full load.

Titanic and her sister ships had been designed with the capability of carrying many more lifeboats than were actually provided, up to a total of 64.[5] During the design stage, Alexander Carlisle, Harland & Wolff's chief draughtsman and general manager, submitted a plan to provide 64 lifeboats. He later reduced the figure to 32, and in March 1910 the decision was taken to reduce the number again to 16.[8] Carlisle is believed to have left his position in dispute of this decision. The White Star Line preferred to maximise the amount of deck space available for the enjoyment of the passengers[17] (and the area that was free of lifeboats was, not coincidentally, the First-Class promenade[18]). The reasoning for this was explained by Archibald Campbell Holms in an article for Practical Shipbuilding published in 1918:

The fact that Titanic carried boats for little more than half the people on board was not a deliberate oversight, but was in accordance with a deliberate policy that, when the subdivision of a vessel into watertight compartments exceeds what is considered necessary to ensure that she shall remain afloat after the worst conceivable accident, the need for lifeboats practically ceases to exist, and consequently a large number may be dispensed with.[19]

Holms made his comments six years after the sinking of Titanic, an indication of the persistence of the view that "every ship should be her own lifeboat". Sailors and shipbuilders of the time had a low opinion of the usefulness of lifeboats in an emergency, as experience showed that small wooden vessels were likely to sink in rough seas (even if properly used and not overloaded), as illustrated by SS Atlantic and Clallam disasters, and therefore considered it more important to make a ship "unsinkable". Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, who served simultaneously as a high-ranking Royal Navy officer and Member of Parliament, told the House of Commons a month after the disaster:

Remember that on not more than one day in twelve all the year round can you lower a boat. With the roll of the ship the boats swing and will be smashed to smithereens against the side of the ship. The boats then should not be overdone ... It might be fairly supposed that had the Titanic floated for twelve hours all might have been saved.[19]

The White Star Line never envisaged that all of the crew and passengers would have to be evacuated at once, as Titanic was considered almost unsinkable. The lifeboats were instead intended to be used to transfer passengers off the ship and onto a nearby vessel providing assistance.[20] While Titanic was under construction, an incident involving the White Star liner RMS Republic appeared to confirm this approach. Republic was involved in a collision with the Lloyd Italiano liner SS Florida in January 1909 and sank. Even though she did not have enough lifeboats for all passengers, they were all saved because the ship was able to stay afloat long enough for them to be ferried to ships coming to assist.[21] This fact is what led to the harsh condemnation of Captain Stanley Lord of the Californian, who both American and British inquiries into the disaster felt could have saved many if not all of the passengers and crew had she heeded the Titanic's distress calls. In this scenario, Titanic's lifeboats would have been adequate to ferry the passengers to safety as planned.[13] However, it is worth noting that the ferrying of passengers between two ships would have been a long, arduous process even under the best conditions. It took Carpathia well over four hours to pick up and account for all of Titanic's lifeboats in the morning after the disaster. During the sinking of the aforementioned Republic in 1909, it took nearly half a day to ferry all of her passengers to rescue ships, and during the sinking of the Italian liner Andrea Doria in 1956 it took nearly eight hours to ferry all her passengers to safety. Both liners sank at a much slower rate, roughly half a day, in contrast to Titanic, which sank slightly shy of three hours after her collision with the iceberg.

While Titanic's supply of lifeboats was plainly inadequate, so too was the training that her crew had received in their use. Only one lifeboat drill had been carried out while the ship was docked. It was a cursory effort, consisting of two boats being lowered, each manned by one officer and four men who merely rowed around the dock for a few minutes before returning to the ship. The boats were supposed to be stocked with emergency supplies, but Titanic's passengers later found that they had only been partially provisioned.[22] No lifeboat or fire drills had been carried out since Titanic left Southampton.[22] A lifeboat drill had been scheduled for the morning before the ship sank, but was cancelled, allegedly because the ship's captain, Edward Smith, wanted to deliver one last Sunday service before he went into full retirement.[23]

Lists had been posted on the ship allocating crew members to particular lifeboat stations, but few appeared to have read them or to have known what they were supposed to do. Most of the crew were, in any case, not seamen, and even some of those had no prior experience of rowing a boat. They were suddenly faced with the complex task of coordinating the lowering of 20 lifeboats carrying a possible total of 1,200 people 70 feet (21 m) down the sides of the ship.[24] Thomas E. Bonsall, a historian of the disaster, has commented that the evacuation was so badly organised that "even if they had the number of lifeboats they needed, it is impossible to see how they could have launched them" given the lack of time and poor leadership.[25]

Launch of the lifeboats

| Lifeboat tally | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Boat | Aboard | Boat | Aboard |

| 2 | 18 | 1 | 12 |

| 4 | 30 | 3 | 32 |

| 6 | 24 | 5 | 36 |

| 8 | 27 | 7 | 28 |

| 10 | 57 | 9 | 40 |

| 12 | 41 | 11 | 50 |

| 14 | 40 | 13 | 55 |

| 16 | 52 | 15 | 66 |

| B | 28 | A | 13 |

| D | 20 | C | 43 |

| Total: | 337 | Total: | 375 |

| Total: | 712 | ||

It was not until about 12:40 A.M., an hour after Titanic struck the iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on 14 April, that the first lifeboat was lowered into the sea. The lifeboats were lowered in sequence, from the middle forward then aft, with First Officer William McMaster Murdoch, Third Officer Herbert Pitman and Fifth Officer Harold Lowe working on the starboard side, and Chief Officer Henry Tingle Wilde, Sixth Officer James Moody and Second Officer Charles Lightoller working on the port side, with the assistance of Captain Smith. The collapsible boats were dealt with last, as they could not be launched until the forward davits were clear.[26]

Smith had ordered his officers to put the "women and children in and lower away".[27] However, Murdoch and Lightoller interpreted the evacuation order differently: Murdoch as women and children first, while Lightoller as women and children only. Lightoller lowered lifeboats with empty seats if there were not any women and children waiting to board, while Murdoch only allowed a limited number of men to board if all the nearby women and children had already embarked. This had a significant effect on the survival rates of the men aboard Titanic, whose chances of survival came to depend on which side of the ship they tried to find lifeboat seats.[28]

Two contemporary estimates were given for the number of occupants in each lifeboat, one by the British inquiry that followed the disaster, and one by survivor Archibald Gracie, who obtained accounts and data from other survivors. However, the figures given–854 persons and 795 persons respectively–far exceed the confirmed number of 712 survivors, due to confusion and misreporting. Some occupants were transferred between lifeboats before being picked up by RMS Carpathia.[29] More recent research has helped to produce estimates of the number of occupants that are closer to the total number of survivors rescued by Carpathia.[30]

Lifeboat 7 (starboard)

Lifeboat 7 was the first lifeboat to be launched at about 12:25 A.M., under the supervision of First Officer Murdoch, supported by Fifth Officer Lowe. It had a capacity of 65 people but was lowered with only 28 estimated people aboard.[30] The two officers had tried for some minutes to encourage passengers to board but they were reluctant to do so.[31] Later testimony at the U.S. Senate inquiry into the disaster stated the ship's officers believed the lifeboats were at risk of buckling and breaking apart if they were lowered while fully loaded. They intended that once the lifeboats reached the water, they would pick up passengers from doors in the ship's side or would pick up passengers in the water. The first did not happen at all and the second only happened in one instance. In fact, the lifeboats had keels reinforced with steel beams to prevent buckling while in the davits (although most of the crew were not aware of this). Moreover, Harland & Wolff's Edward Wilding testified that the lifeboats had in fact been tested safely with the weight equivalent of 70 men. However, the results had not been passed on to the crew of Titanic.[8] A significant degree of negligence in the training and continuing education of officers and crew in the White Star Line seems apparent, especially when noting the improper manner in which distress rockets were actually fired that night (regulations called for firing at one-minute intervals).

Among the occupants of Lifeboat 7 were:

- Dorothy Gibson, American silent film actress who starred in Saved from the Titanic (1912), the first motion picture produced about the disaster

- Pauline Caroline Boesen, Gibson's mother

- Frederic Kimber Seward, prominent New York corporate lawyer

- William T. Sloper, Connecticut banker, who was falsely accused of dressing as a woman to get into the lifeboat

- Archie Jewell, Lookout[32]

- Margaret Hays, New York heiress, who brought her Pomeranian, Bebe, with her

- Alfred Nourney, traveling under the pseudonym Baron Alfred von Drachstedt

- Dickinson Bishop, businessman (who was also falsely accused of dressing as a woman that night) and his new wife Helen

- Antoinette Flegenheim, German socialite

- John Pillsbury Snyder, banker, and his new wife Nelle

The lifeboat was launched without its plug, causing water to leak into the bottom of the boat. As Gibson later put it, "this was remedied by volunteer contributions from the lingerie of the women and the garments of men."[33] Those aboard had to sit for hours with their feet soaking in ice-cold water.[34] When Titanic went down at 2:20 A.M., the noise of hundreds of people screaming for help was heard by the lifeboat's occupants, a sound that Gibson said would "remain in my memory until the day I die." George Hogg, a Titanic lookout manning the boat, wanted to turn back to pick up some of those in the water but was shouted down by the boat's occupants.[35] They drifted for some time until they came within reach of Lifeboat 5. The officer in charge of the latter decided to transfer a number of survivors from his boat, which he thought was overcrowded, into Lifeboat 7.[36] The two boats were lashed together for the rest of the night until they separated to meet the RMS Carpathia.[37]

Lifeboat 5 (starboard)

Murdoch and Lowe were joined by Third Officer Pitman and the White Star Line's chairman J. Bruce Ismay to help them lower Lifeboat 5, which left at 12:28 A.M.[30] The boat was loaded primarily with women and children.[38] Most of those on deck were unaware of the seriousness of their situation and did not even attempt to board. John Jacob Astor, who was subsequently among the victims of the disaster, remarked: "We are safer on board the ship than in that little boat."[39] Ismay disagreed; still wearing slippers and pajamas, he urged Pitman to begin loading the boat with women and children. Pitman retorted: "I await the Captain's orders,"[40] and went to the captain for the approval. Ismay returned a short time later to urge a stewardess to board, which she did. In the end, about 37 estimated people boarded, including Pitman himself, on Murdoch's orders.[30] Four year-old Washington Dodge Jr. was the first child to enter a lifeboat.

The occupants included:

- Karl Behr, American tennis star and banker, along with his future fiancée and her parents Sallie and Richard Beckwith

- Third Officer Herbert Pitman, put in charge of the boat by Murdoch.[38]

- Quartermaster Alfred John Olliver

The boat's progress down the side of the ship was slow and difficult. The pulleys were covered in fresh paint and the lowering ropes were stiff, causing them to stick repeatedly as the boat was lowered in jerks towards the water. One of those watching the boat being lowered, Washington Dodge, felt "overwhelmed with doubts" that he might be subjecting his wife and son to greater danger aboard the boat than if they had remained on Titanic.[41] Ismay sought to spur those lowering the boat to greater urgency by calling out repeatedly: "Lower away!" This resulted in Lowe losing his temper: "If you'll get the hell out of the way, I'll be able to do something! You want me to lower away quickly? You'll have me drown the lot of them!" The humiliated Ismay retreated up the deck. In the end, the boat was launched safely.[41]

After Titanic sank, several of those aboard Lifeboat 5 were transferred to Lifeboat 7, leaving about 30 on board by the time Lifeboat 5 reached Carpathia.[30] Herbert Pitman wanted to return to the scene of the sinking to pick up swimmers in the water and announced: "Now men, we will pull toward the wreck!" The women on board protested, one begging a steward: "Appeal to the officer not to go back! Why should we lose all our lives in a useless attempt to save others from the ship?" Pitman gave in to the protests but was haunted by guilt for the rest of his life.[42]

The occupants of the lifeboat endured a freezing night. Mrs. Dodge was particularly badly affected by the cold but was helped by Quartermaster Alfred Olliver, who gave her his socks: "I assure you, ma'am, they are perfectly clean. I just put them on this morning."[43] At about 6:00 A.M., they were rescued by Carpathia.[44]

Lifeboat 3 (starboard)

Lifeboat 3 was launched at 12:55 A.M. by Murdoch and Lowe with 32 estimated people on board, with Able Seaman George Moore put in charge by Murdoch.[30]

Railroad manager Charles Melville Hays saw his wife, Clara (along with her maid) and his daughter Orian Davidson into Lifeboat 3 and then retreated, making no attempt to board any of the remaining lifeboats.[45] Margaret Brown later described the scene in an interview with The New York Times:

The whole thing was so formal that it was difficult for anyone to realise it was a tragedy. Men and women stood in little groups and talked. Some laughed as the boats went over the side. All the time the band was playing...I can see the men up on deck tucking in the women and smiling. It was a strange night. It all seemed like a play, like a dream that was being executed for entertainment. It did not seem real. Men would say "After you" as they made some woman comfortable and stepped back.[45]

The occupants included:

- Henry S. Harper, a member of a New York City publishing firm, who also brought into the boat his Pekinese dog Sun Yat Sen, along with his wife Myra and their manservant.

Eleven crewmen were among the occupants of this boat.[46] It suffered the same problems with lowering that Lifeboat 7 had encountered, with the lifeboat descending in fits and starts as the lowering ropes repeatedly stuck in the pulleys, but eventually reached the water safely.[47] After Titanic sank, the lifeboat drifted, while the bored women passengers passed the time by arguing with each other over minor annoyances.[48] The occupants had a long wait in freezing conditions and were not rescued until about 7.30 A.M. when Carpathia arrived.[44]

Lifeboat 8 (port)

Lifeboat 8 was loaded with 27 estimated people under the supervision of Captain Smith and Chief Officer Wilde, being launched at 1:00 A.M. Lifeboat 8 was the first lifeboat on the port side to be lowered. Ida Straus, wife of New York merchant Isidor Straus, was asked to join a group of people preparing to board but refused, saying, "I will not be separated from my husband. As we have lived, so will we die – together." The 67-year-old Isidor likewise refused an offer to board on account of his age, saying: "I do not wish any distinction in my favor which is not granted to others." They were last seen alive on deck arm in arm.[49] Major Archibald Butt – military aide to US President William Howard Taft – escorted Marie Young to the boat. She later recalled that Butt "wrapped blankets about me and tucked me in as carefully as if we were going on a motor ride." He wished her farewell and good luck, asking her to "remember me to the folks back home."[50] Other single women were brought to the boats by men who had earlier offered their services to "unprotected ladies", as the conventions of the era dictated.[50]

The occupants of Lifeboat 8 numbered around 27 people,[30] including:

- Noëlle, Countess of Rothes, who took charge of the lifeboat's tiller and helped row, along with her maid and husband's cousin, Gladys Cherry

- Marie Grice Young, former music teacher to the children of President Theodore Roosevelt and Mrs. Roosevelt

- Ella Holmes White

After Titanic sank, Seaman Thomas William Jones, in command of the boat, suggested going back to save some of those in the water. Only three passengers agreed; the rest refused, fearing that the boat would be capsized by desperate swimmers. Jones acquiesced, but told them: "Ladies, if any of us are saved, remember I wanted to go back. I would rather drown with them than leave them."[50] The passengers' conduct during the subsequent hours presented some striking contrasts. Lady Rothes – who had been one of the few passengers to support a rescue attempt – took charge of the tiller and put others to work at the oars.[51] Her conduct was later complimented by Jones, who called her "more of a man than any we had aboard" and gave her the lifeboat's numeral 8, in a frame, as a keepsake. In fact, when Walter Lord, author of A Night to Remember, interviewed the Countess and Seaman Jones in 1954, he discovered their mutual admiration had led to a lifelong correspondence.[52] By contrast, Ella White was so annoyed that the stewards in Lifeboat 8 were smoking cigarettes that she complained about it at the US Senate inquiry into the disaster;[48] she was particularly indignant that one of the ship's crewmen had said to another during the night: "If you don't stop talking through that hole in your face, there will be one less in the boat!"[51]

The occupants of Lifeboat 8 spent the night rowing towards what they thought were the lights of a ship on the horizon but turned around at daybreak when Carpathia actually arrived on the scene from the opposite direction. They had travelled further from the scene than any other lifeboat and had a long row back;[53] It was not until 7:30 A.M. that they were picked up.[44]

Emergency Lifeboat 1 (starboard)

Lifeboat 1 was the first Emergency Lifeboat to be launched at 1:05 A.M. under the supervision of Murdoch and Lowe. It became one of the most controversial episodes in the aftermath of the disaster, both because the craft only contained 12 people and because of the alleged misconduct of two of its occupants, Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon and his wife, Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, famous as the dress designer "Lucile" of London, Paris and New York. The boat was one of Titanic's two emergency cutters with a capacity of 40.[49] Of the twelve people aboard, seven were crewmen and the remaining five were First-Class passengers.[54]

Its composition was not, however, a departure from Murdoch's interpretation of the "women and children first" directive. He had already allowed several married couples and single men to board lifeboats. Cosmo Duff-Gordon had been standing on deck with his wife and her secretary, Laura Mabel Francatelli, watching the launching of three other lifeboats when, as Lifeboat 1 was being prepared, he asked Murdoch if his party could board. Murdoch assented and also allowed two Americans, Abram Salomon and Charles E. H. Stengel, to enter. He then instructed a group of six stokers to board, along with Lookout George Symons,[49] whom he placed in charge of the boat. As the craft was lowered, Greaser Walter Hurst, watching the procedure from a lower deck, remarked to a crewmate: "If they are sending the boats away, they might as well put some people in them."[55]

The census conducted on the cutters by Harland & Wolff concluded that Lifeboat 1 had room for about another 28 passengers. However, Lifeboat 1 would not return to rescue those in the water after Titanic sank. Fireman Charles Hendrickson claimed he told his boat mates: "It's up to us to go back and pick up anyone in the water!" but found no support.[42] At least three other crewmembers, as well as the Duff-Gordons, Salomon and Stengel, denied hearing any suggestion to go back or opposing any proposition to do so. In the media later, the passenegers – the Duff-Gordons in particular – were widely criticised for what was interpreted as their callousness in the face of the disaster. For instance, as Titanic sank, Lucile reportedly commented to her secretary: "There is your beautiful nightdress gone." Fireman Pusey replied that she should not worry about losing her belongings because she could buy more. Pusey mentioned that the crew had lost all their kit and that their pay stopped from the moment of the sinking. Cosmo responded: "Very well, I will give you a fiver each to start a new kit!" Aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, he did as he promised, presenting each of the seven crewmen in his lifeboat a cheque for £5.

When this act was made public, it was interpreted by much of the press as a bribe to prevent the crew from returning to the scene of the sinking to rescue others. The British Board of Trade's official inquiry into the disaster investigated the allegation but found the charge of bribery to be false. Even so, the publicity injured Cosmo's reputation.[54] A photograph of the occupants of Lifeboat 1 was taken aboard the Carpathia. Lucile had consented to a request from a Carpathia passenger, Frank Blackmarr, to take the image, but the sight of some of the crew posing in their lifejackets disturbed some fellow survivors who subsequently complained about the incident.[56]

Lifeboat 6 (port)

Smith and Second Officer Lightoller launched Lifeboat 6 at 1:10 A.M.; it was photographed as it approached Carpathia, revealing it to have about 24 people aboard, though it had a capacity of 65.[30] Denver millionaire Margaret "Molly" Brown was among Lifeboat 6's most prominent occupants, along with Washington, D.C. writer and feminist Helen Churchill Candee, and English suffragettes Edith Bowerman and her mother Mrs. Edith Chibnall. Brown did not board voluntarily but was picked up by a crewman and dropped bodily into the boat as it was being lowered. Quartermaster Robert Hichens was placed in charge of the craft along with lookout Frederick Fleet. While being lowered, pleas from women in the boat for additional oarsmen forced Lightoller to solicit the crowd on deck for anyone who had sailing experience. Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club volunteered, shinnying down the falls (ropes) into the boat.[38] Peuchen was the only adult male passenger whom Second Officer Lightoller permitted to board a lifeboat.

Relations among the occupants of Lifeboat 6 were strained throughout the night. Hichens apparently resented Peuchen's presence, perhaps fearing the Major would pull rank and take charge. The two men quarreled, and Hichens refused Peuchen's request that he assists him at the oars, since there was only one other man (Fleet) rowing.

When Titanic sank, Peuchen, Brown and others urged Hichens to return to rescue people struggling in the water. Hichens refused, even ordering the men at the oars to stop rowing altogether. "There's no use going back," he called out. "There's only a lot of stiffs out there," adding: "It's our lives now, not theirs."[57] The cries for help soon died. Brown now asked Hichens to let the women row to help keep them warm. When he balked, Brown ignored him and started passing out oars anyway. He protested and swore at her, and at one point moved to physically stop her. She told him to stay put or she would throw him overboard. Others joined in to back her up, telling Hichens to keep quiet. But he continued swearing, shocking a stoker (transferred from Lifeboat 16) who finally asked him: "Don't you know you're talking to a lady?" Taking an oar herself, Brown organised the other women in shifts, two to an oar. When her heroic actions were published in the press, she became known as the "Unsinkable Molly Brown."[58] Brown's leadership was supported by Helen Candee, who herself assisted in the rowing despite a broken ankle received when she fell into the boat while boarding.[59]

After Titanic sank, Lifeboat 6 eventually tied up with Lifeboat 16. It was one of the last to reach Carpathia, coming alongside at 8:00 A.M.[44] Mrs. Elizabeth Rothschild had her Pomeranian with her in the lifeboat. Initially, crew members of the Carpathia refused to take the dog aboard, but Mrs. Rothschild would not board the rescue ship without it. The Pomeranian was one of only three dogs to survive the disaster.[60]

- Elsie Edith Bowerman and her mother Mrs. E. M. Chibnall

- Margaret Brown

- Helen Churchill Candee, noted American author

- Lookout Frederick Fleet - the man who had first sighted the iceberg

- Arthur Godfrey Peuchen, Toronto chemical manufacturer

- Mary Eloise Smith

Lifeboat 16 (port)

Chief Officer Wilde and Sixth Officer Moody supervised the launching of Lifeboat 16 at about 1:20 A.M. 53 people are believed to have been on board by the time it reached Carpathia;[61] Most of those aboard were said to be women and children from Second and Third-Class. Master-at-arms Joseph Henry Bailey was put in charge of the lifeboat along with Seamen Ernest Archer and James Forward.[62][63]

Very few testimonies mention Lifeboat 16 which did not interact much with the other boats (but encountered Lifeboat 6 and gave them a fireman for rowing). Third Class passenger Carla Andersen-Jensen who was very likely in this Lifeboat 16 gave a detailed depiction of the disaster:

“[...] We were now up on the deck and there were not much commotion, we had hit an iceberg, but everyone felt the ship would stay afloat. The ship was fully lit and there was music in the 1st class saloon. There were no panic even when the lifeboats were launched, no one seem to push to get into them and the women and children went into the boats first. When the lifeboat I got into rowed away from Titanic the orchestra was still playing. One said later it was the psalm Nearer My God to Thee [...] Then the catastrophe happened. Before anyone expected it. With fright we heard an incredible crash and it was as if a scream from 1000 voices came from the lit giant ship, when it broke in two and both parts rose into the sky and sank. We sat like stone figures and saw it all happen. What was even worse than the screams were the deadly silence that came after.....it was frightful. We could not handle anything when we were taken onboard the freighter [...]. We were put in the hold or where there was room, we were well taken care of and got food and warm drinks. However the hours on board were frightful, some women were just sitting apathetically and staring out into the air and others were wandering around screaming their men's names. Some were lying around just crying and others could not handle the event and several times we saw canvas-covered bodies being lowered over the side”.[64]

Among the occupants of the lifeboat was also:

- Stewardess Violet Constance Jessop, who survived the accidents that befell all of the Olympic-class liners: the collision of Olympic with HMS Hawke in 1911, the sinking of Titanic in 1912, and that of Britannic in 1916.[65]

- Margaret Mannion along with her best friend Ellen Mockler[66]

- Stewardess Evelyn Marsden

- Stewardess Elizabeth Leather[67][68] who was one of only two stewardesses subpoenaed to testify at the Board of Trade Inquiry into the sinking (the other being Annie Robinson[69])

Lifeboat 14 (port)

40 passengers were aboard Lifeboat 14, with Wilde, Lightoller, Lowe and Moody supervising its launch.[61] By the time it was launched at about 1:25 A.M., Titanic was well down in the water. Lowe fired three shots from his revolver to warn off a crowd of passengers pressing up against the rails.[70] As the boat was lowered, a young man climbed over the rails and tried to hide under the seats. Lowe ordered him to leave at gunpoint, first threatening to "Throw him over-board", then appealing to him to "be a man – we've got women and children to save." The passenger returned to the deck where he was left lying face-down to await his fate.

The boat reached the water safely, with Lowe himself aboard to take charge. After Titanic sank, he brought together Lifeboats 4, 10, 12 and Collapsible Boat D, and transferred Lifeboat 14's passengers to the other lifeboats. Then, assembling a crew of volunteers, he took his boat back to the scene of the sinking to try and find survivors. Lifeboat 4 was the only other lifeboat to rescue people from the sea. By the time Lowe's boat reached the scene of the sinking, the sea was filled with the bodies of hundreds of people who had died of hypothermia. Four men (Steward Harold Phillimore, First-Class passenger William Fisher Hoyt, Third-Class passenger Fang Lang and a fourth unknown person, possibly Second-Class passenger Emilio Ilario Giuseppe Portaluppi, were pulled from the sea but most were already dead or dying.[61][71] Hoyt died in the boat, while the other three survived.

A few hours later, Lowe rescued the survivors aboard Collapsible Boat A, which was close to sinking, and brought them aboard Lifeboat 14.[72] An experienced sailor, Lowe set up the lifeboat's mast and sail for better speed and maneuverability while searching for survivors, making it the only lifeboat to avail of sail power.[73] The boat rendezvoused with Carpathia at about 7:15 A.M.[44]

Among the survivors in Lifeboat 14 were:

- Eva Hart and her mother, Esther

- Edith Eileen Brown and her mother, Elizabeth

- Harold Godfrey Lowe (in charge)

- Charles Eugene Williams, racquets player[74]

Lifeboat 12 (port)

Chief Officer Wilde and Second Officer Lightoller lowered Lifeboat 12 at 1:30 A.M. at the same time as Lifeboat 9. It was first manned only by Able Seaman Frederick Clench and was subsequently put in the charge of Able Seaman John Poingdestre. A male passenger jumped into the boat as it was lowered past B Deck. Difficulty was encountered in unhooking the boat from the falls, requiring Poingdestre to use a knife to cut through the ropes.

Several passengers from other boats were transferred into Lifeboat 12 after the sinking. Lifeboat 12 encountered Lifeboats 4, 10, 14 and Collapsible D in sea. Fifth Officer Lowe in charge of Lifeboat 14 distributed 10 or 12 additional survivors to Lifeboat 12 (in order to go back himself with some seamen to the wreckage to see if he could save anyone). Lifeboat 12 probably received also 2 or 3 crew from Collapsible D to get to 40-45 people at this time. After that, Lifeboat 12 together with Lifeboat 4 heard Second Officer Lightoller's whistle (standing with some survivors on overturned Collapsible B), they rowed off and rescued about 16 or so people standing on the bottom of overturned Collapsible B. Lifeboat 12 passed then under the command of Second Officer Lightoller.[75] It was heavily overloaded by the time with at least between 60[76] and 70 people aboard.[70][77] It was the last lifeboat to be picked up by Carpathia, at about 8:30 A.M.[44]

The occupants of Lifeboat 12 numbered initially (prior to transfer of passengers and rescue operation) around 28-30 people (mainly Second class passengers), including:

- John Thomas Poindegstre (in charge)

- Frederick Charles Clench (in charge)

- Lillian Winifred Bentham

- Dagmar Jenny Ingeborg Bryhl

Lifeboat 9 (starboard)

The lowering of Lifeboat 9 at 1:30 A.M., at the same time as Lifeboat 12, carried 40 passengers aboard and was supervised by Murdoch, Moody and Purser McElroy.[77] Boatswain's Mate Albert Hames was put in charge with Able Seaman George McGough at the tiller.[61] Most passengers were women, with two or three men who entered when no more women came forward. One elderly woman refused to board, making a great fuss, and retreated below decks. May Futrelle, the wife of novelist Jacques Futrelle, was likewise initially reluctant to board; but after her husband told her, "For God's sake, go! It's your last chance! Go!", an officer forced her into the boat.[49] The millionaire Benjamin Guggenheim brought Léontine Aubart, his French mistress, and her maid, Emma Sägasser, to Lifeboat 9 before retiring to his stateroom with his secretary, Victor Giglio. Both men removed their life jackets and put on their evening clothes. Guggenheim told a steward,

We've dressed in our best, and are prepared to go down like gentlemen. There is grave doubt that the men will get off. I am willing to remain and play the man's game if there are not enough boats for more than the women and children. I won't die here like a beast. Tell my wife I played the game out straight and to the end. No women shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward.[78]

Kate Buss and her friend, Marion Wright, were standing with their shipboard acquaintances Douglas Norman and Dr. Alfred Pain, watching the boats being lowered, when a call came for "Any more ladies". The two men brought Buss and Wright to Lifeboat 9, who beckoned Norman and Pain to join them. However, the men were barred from entering by crewmen on the deck. Horrified, Buss demanded to know why they had not been allowed aboard. Hames told her, "The officer gave the order to lower away, and if I didn't do so he might shoot me, and simply put someone else in charge, and your friends would still not be allowed to come." Norman and Pain both perished in the disaster.[79] The lifeboat was picked up by Carpathia several hours later, at about 6:15 A.M.[44]

Lifeboat 11 (starboard)

Lifeboat 11 was lowered under Murdoch's supervision at 1:35 A.M. with Able Seaman Sidney Humphreys in charge. By now the lifeboats were being filled much closer to capacity. Lifeboat 11 is estimated to have carried 50 people.[77] One occupant, Steward James Witter, was knocked into the boat by a hysterical woman whom he was helping aboard as it was lowered.[80] First-Class passenger Edith Louise Rosenbaum, a Paris-based correspondent for Women's Wear Daily, brought along her toy pig, a music box that played the Maxixe and had been given to her as a good luck token by her mother. She was too frightened to enter the lifeboat, but when a crew member, mistaking her toy for a baby, tossed it in, she leaped in after it.[79] The toy pig is now part of the collection of the National Maritime Museum in London.[81] Second-Class passenger Nellie Becker protested her way into Lifeboat 11, after an officer placed her son and younger daughter in the boat. She was initially prohibited from entering by Murdoch, who felt the boat was already too full, but eventually made her way aboard. In the chaos, however, her elder daughter Ruth was left behind and was instructed by Murdoch to head for Lifeboat 13.

On reaching the water, Lifeboat 11 was nearly swamped by a jet of water being pumped out from the ship to stem the flooding. Tempers flared among the crowded passengers, some of whom had to stand, as the boat was rowed away from the ship.[82] Rosenbaum offered some levity by using her musical pig to entertain the children underfoot.[79] The lifeboat was met by Carpathia at about 7:00 A.M.[44]

- Alice Catherine Cleaver, nursemaid to the Allison's infant son Trevor, whom she brought with her into the boat

- Edith Louise Rosenbaum, American fashion designer

Lifeboat 13 (starboard)

Lifeboat 13 was partially filled from the Boat Deck and partially from A Deck after it had been lowered to that level when it was launched under the supervision of Murdoch and Moody at 1:40 A.M. Again, it was heavily occupied, with 55 people aboard and Leading Fireman Frederick Barrett in charge.[77] The occupants were mainly Second- and Third-Class women and children. Among the men aboard was Lawrence Beesley, who subsequently wrote a popular book about the disaster.[83] Dr. Washington Dodge was also aboard, having earlier seen his wife and young son aboard Lifeboat 5. He owed his presence aboard the boat to the apparent guilty feelings of Steward F. Dent Ray, who had urged the Dodges to sail on Titanic in the first place. Just before Lifeboat 13 was lowered, Ray bundled Dodge aboard.[84] 12-year-old Second-Class passenger Ruth Becker was placed in this boat by Moody after being prevented from entering the heavily overloaded Lifeboat 11, which her mother and two siblings had boarded. She was one of the few passengers who brought blankets from her stateroom into a lifeboat, which were later used to keep the stokers, who were wearing sleeveless shirts, warm while rowing. Others did not want to board at all. A woman on deck panicked, crying, "Don't put me in that boat! I don't want to go in that boat! I've never been in an open boat in my life!" Ray told her, "You have got to go and you may as well keep quiet."[79]

One male survivor, Daniel Buckley, reputedly managed to get into Lifeboat 13 thanks to a female passenger who concealed him under her shawl.[85] Buckley, a Third-Class passenger from County Cork in Ireland,[86][87][88] was emigrating to the United States with a group of cousins and friends.[89] He was among a group of steerage passengers who forced their way through a locked gate to the boat deck. He testified to the Senate inquiry into the sinking that he had helped put women and children in at least five lifeboats when he made a quick decision to jump in with a number of males. Buckley testified that, when two officers ordered the men to get out, a female passenger took pity on him, threw a shawl over him and pushed him down to hide him in the bottom of the boat.[89] He believed that his savior was Madeleine Astor, though she was in Lifeboat 4. Buckley later joined the 69th Infantry Regiment of the US Army during World War I and was killed in action on 15 October 1918 during the Meuse–Argonne offensive. Buckley is credited with writing the folk song Sweet Kingwilliamstown.[87]

While it was being lowered, Lifeboat 13 was nearly swamped by "an enormous stream of water, three or four feet in diameter"[90] coming from the condenser exhaust which was being produced by the pumps, far below, trying to purge the water that was flooding into Titanic. The occupants had to push the boat clear using their oars and spars and reached the water safely. The wash from the exhaust caused the boat to drift directly under Lifeboat 15, which was being lowered almost simultaneously. Its lowering was halted just in time, with only a few feet to spare. The falls aboard Lifeboat 13 jammed and had to be cut free to allow the boat to get away safely from the side of Titanic.[91] According to passenger Delia McDermott, she climbed out of the boat early on to recover her new hat.[92] A few hours later the occupants saw Carpathia coming to their rescue and began rowing towards it to an accompaniment of the Philip P. Bliss hymn,[93] "Pull for the Shore".[94] They were picked up at about 6:30 A.M.[77]

- Leading Fireman Frederick William Barrett (in charge)

- Fireman George William Beauchamp

- Lawrence Beesley, English science master, who later wrote one of the first cogent accounts of the disaster

- Daniel Buckley, Irish immigrant

- Lookout Reginald Robinson Lee

- Dining Room Steward Frederick Dent Ray

- Ellen Shine, Irish immigrant

Lifeboat 15 (starboard)

Murdoch and Moody oversaw the lowering of Lifeboat 15, concurrently with Lifeboat 13 and it reached the water only a minute later, at 1:41 A.M. Fireman Frank Dymond was put in charge of what was the most heavily loaded boat at launching. It was so heavily loaded, with about 68 people, that the gunwales were reported to be far down in the water; one female passenger later said that when she leaned against the gunwale her hair trailed in the water.[77] The boat was one of the last to be recovered by Carpathia, at about 7:30 A.M.[44]

Occupants of Lifeboat 15 included:

- Lillian Gertrud Asplund, her mother Selma, and her younger brother Felix. Her father and three older brothers were left behind and lost.

- Fireman Arthur John Priest, who later survived the sinking of the Britannic in 1916.

Emergency Lifeboat 2 (port)

The lowering of Lifeboat 2, the second of the two cutters, was overseen by Smith, Wilde and Fourth Officer Boxhall at about 1:45 A.M.[77] When Wilde moved from Lifeboat 12 to Lifeboat 2 to get it ready for loading, he found that it was already filled with a large group of male passengers and crewmen. He ordered them out at gunpoint, telling them, "Get out of there, you damned cowards! I'd like to see every one of you overboard!" They fled. Even at this late stage, some lifeboats were leaving with plenty of space aboard; Lifeboat 2 appeared to have been lowered with only approximately 18 people aboard, out of a capacity of 40.[77] The occupants were principally women, plus one male Third-Class passenger, Anton Kink, who joined his wife and young daughter in the boat. Boxhall was given charge of the boat by Smith.[77]

When Titanic sank at 2:20 A.M., Boxhall suggested to the occupants that they should go back to pick people up from the water. However, they refused outright. Boxhall found this puzzling, as only a short time before the women had pleaded with Smith for their husbands to be allowed to accompany them, yet now they did not want to go back to save them (although actually only one woman, Mrs. Walter Douglas, had left a husband on board).[42] The lifeboat was the first to reach Carpathia, at 4:10 A.M.[44]

The occupants of Lifeboat 2 numbered around 18 people, including:

- Joseph Groves Boxhall (in charge)

- Louise Kink and her parents, Anton and Louise

Lifeboat 4 (port)

Launched concurrently with Lifeboat 10, with about 34 people aboard, Lifeboat 4 was the last of the wooden lifeboats launched under the supervision of Lightoller at 1:50 A.M. with Quartermaster Walter Perkis put in charge.[95] It was actually one of the first lifeboats to be lowered on Captain Smith's suggestion that passengers should be loaded from the Promenade Deck rather than the Boat Deck. However, the captain had forgotten that– unlike on his previous command, Titanic's sister ship Olympic – the forward half of the Promenade Deck was enclosed. Lightoller ordered that the windows on the Promenade Deck's enclosure were to be opened and moved on to deal with the other lifeboats.[96] The windows proved unexpectedly difficult to open and to add to the problems, the lifeboat got caught up on Titanic's sounding spar, which projected from the hull immediately below the boat. The spar had to be chopped off to allow the lifeboat to progress. A stack of deck chairs was used as a makeshift staircase to allow passengers to climb up and through the windows and into the boat.[97]

Among the occupants was Madeleine Astor, the pregnant wife of the American millionaire John Jacob Astor. She had endured a long wait, shuttling back and forth between the Promenade and Boat Decks as plans for loading the boat were made and discarded. Now she boarded, accompanied by her maid and nurse, and helped by Astor, who asked Lightoller if he could join her. Lightoller refused, telling him, "No men are allowed in these boats until the women are loaded first." Astor told Madeleine, "The sea is calm. You'll be all right. You're in good hands. I'll meet you in the morning." He did not survive.[97]

The Carters also reached Lifeboat 4. William Carter helped his wife, Lucile, and daughter, also named Lucile, into the boat, but his son, Billy, had to leave his tan-and-black Airedale dog before he was allowed in the boat.

Of the seven members of the Ryerson party from First-Class, only the five females were initially allowed to board, including Emily, her two daughters, Emily and Susan, the maid, and the governess. The son, John, was not allowed until his father Arthur stepped forward, proclaiming, "Of course, that boy goes with his mother. He is only 13."[98] All survived except Arthur, who stayed behind.[99]

As it had been ordered, Perkis steered the boat along the side of the ship in search for open gangways, since he had been told to take more passengers on board but found no one. This way, the lifeboat ended up near the davits of Lifeboat 16 (which had been already launched), and two greasers, Thomas Ranger and Frederick William Scott, who were standing near them, climbed down the falls to Lifeboat 4 (Scott fell into the water but was hauled aboard the lifeboat).[100][101] The boat then rowed away from the ship in order to avoid suction.[102] A third man, lamp trimmer Samuel Ernest Hemming, climbed down the falls of another lifeboat and swam over to Lifeboat 4, which was about 200 yards away.[103] Immediately after the sinking, the lifeboat rowed back to the wreckage to pick up more survivors (the only lifeboat to try immediately to do so).[100] It picked up six or seven more men (trimmer Thomas Patrick Dillon, Seaman William Henry Lyons, Stewards Andrew Cunningham and Sidney Conrad Siebert, storekeeper Frank Winnold Prentice,[103][104][105] Two (Siebert and Lyons) later died of exposure.[104][105] and one or two more unidentified swimmers. Two of the names that were given is that of greaser Alfred White and Emilio Portaluppi. Lamp trimmer Hemming said that one of the swimmers picked up from the sea was a foreign passenger who spoke English well. This could very well have been Emilio Portaluppi who was an Italian that had lived in the U.S. for many years. Portaluppi rather embellished, granted – accounts to his family he claimed to have been saved by the lifeboat that had Madeleine Astor in it, that is Boat 4 from the water. The number of occupants later increased when other people were transferred from Lifeboat 14 and Collapsible Boat D. By the time it reached Carpathia at 8:00 A.M. it had about 60 occupants including:[106]

- Madeleine Talmage Astor, pregnant wife of the wealthiest man aboard, and her maid and nurse

- Lucile Polk Carter, and her daughter Lucille and son William, and maid

- Emily Borie Ryerson, and her children Susan, Emily, and Jack, and her maid and son's governess

- Marian Longstreth Thayer, whose son was rescued from Collapsible Boat B, and her maid

- Eleanor Widener, who lost both her husband George and son Harry, and her maid

Lifeboat 10 (port)

Lifeboat 10 was launched at the same time with Lifeboat 4, under the supervision of Wilde and Murdoch at about 1:50 A.M. with Able Seaman Edward Buley in charge. It appeared to have had 57 people aboard when it was launched.[77] By this time Titanic was listing to port, making it increasingly difficult to launch lifeboats from that side of the ship, as the ship's list had created a gap of about 3 feet (0.9 m) between the deck and the sides of the port-side lifeboats. An attempt to board by a young French woman nearly ended in disaster when she jumped into the lifeboat, fell short and dropped into the gap. She was caught by the ankle by Dining Room Steward, William Burke,[107] and was pulled back on board the ship by a person on the deck. She made it into the lifeboat safely on her second attempt. Titanic was clearly not far from sinking and this realisation led to an increased urgency to load the lifeboat; children were rushed aboard, one baby literally being thrown in and caught by a female passenger. Neshan Krekorian, an Armenian passenger from Third-Class, is said to have jumped into Lifeboat 10 as it was being lowered.[108] Among the passengers of Lifeboat 10, was the youngest Titanic passenger, nine-week-old Millvina Dean, who was also the last remaining survivor.[109] She accompanied her mother, Mrs. Etta Dean, and older brother, Bertram. Two of those aboard were later transferred to another lifeboat, and it had 55 aboard when it met Carpathia a few hours later.[77] It was the second to last lifeboat to be picked up, at 8:00 A.M.[44] The occupants of Lifeboat 10 numbered around 57 people, including:

- Able Seaman Frank Oliver Evans, who later transferred to Lifeboat 14

- Elizabeth Gladys 'Millvina' Dean, the youngest (and last surviving) passenger on board, and her mother Georgette and brother Bertram

- Masabumi Hosono, a Japanese civil servant who jumped into the lowering boat and spent the night rowing

- Barbara West, and her pregnant mother Ada and sister Constance

Collapsible Engelhardt Lifeboat C (starboard)

Wilde and Murdoch oversaw the launch of the first of the collapsible Engelhardt lifeboats, which was retrieved from its stored position, the sides erected, and the lifeboat attached to the davits. The majority of the forward boats had gone by this time and most of the crowd on deck had moved aft as Titanic's bow dipped deeper into the water.[65] The lifeboat was rushed by a group of stewards and Third-Class passengers who tried to climb aboard but were driven back by Purser McElroy, who fired two warning shots into the air, while Murdoch tried to hold the crowd back. Two First-Class passengers, Hugh Woolner and Swedish industrialist Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, came to the officers' assistance and dragged out two stewards who had made it into the lifeboat. With the assistance of Woolner and Steffansson, Murdoch and Wilde managed to load the lifeboat quickly but calmly. White Star Line Chairman J. Bruce Ismay also assisted by rounding up women and children to bring them to Collapsible Boat C. Captain Smith, who was observing events from the starboard bridge wing, ordered Quartermaster George Rowe to take command of the boat.[110] After Wilde called repeatedly for women and children to enter, a number of men took up the remaining spaces in the lifeboat, including Ismay; his decision to save himself ultimately proved to be very controversial.[65]

The lifeboat was lowered into the water at 2:00 A.M. and was the last starboard-side boat to be successfully launched. By now Titanic was listing heavily to port, and the boat collided with the ship's hull as it descended towards the water. Those aboard used their hands and oars to keep the boat clear of the side of the ship.[65] As Titanic went down 20 minutes later, Ismay turned his back on the sinking ship, unable to bear the sight.[111] It was the first of the collapsible lifeboats to reach Carpathia, at 5:45 A.M., and had about 43 people on board, including:

- Frank John William Goldsmith, and his mother Emily. His father was lost.

- Joseph Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line

- William E. Carter, whose family had already been rescued in Lifeboat 4

Collapsible Engelhardt Lifeboat D (port)

By the time Collapsible Boat D was launched at 2:05 A.M., there were still 1,500 people on board Titanic and only 47 seats in the lifeboat. Crew members formed a circle around the boat to ensure that only women and children could board. It was launched under the supervision of Wilde and Lightoller. Collapsible Boat D was the last boat to be launched from Titanic; the rest were washed off the deck.[65] Two small boys were brought through the cordon by a man calling himself "Louis Hoffman". His real name was Michel Navratil; he was a Slovak tailor who had kidnapped his sons from his estranged wife and was taking them to the United States. He did not board the lifeboat and died when the ship sank. The identity of the children, who became known as the "Titanic Orphans", was a mystery for some time after the sinking and was only resolved when Navratil's wife recognised them from photographs that had been circulated around the world. Four-year-old Michael Joseph Yusuf, who was earlier separated from his mother and sister, was placed in the lifeboat by crew members. The three boys were the last children to be rescued in a lifeboat. The elder of the brothers, Michel Marcel Navratil, was the last living male survivor of the disaster.[112] First-Class passenger Archibald Gracie began escorting female passengers to the front of the ship. After spotting passengers Caroline Brown and Edith Evans together, he took them to the lifeboat - one on each arm. First-Class passenger Edith Evans gave up her place in the lifeboat to Caroline Brown, who became the last passenger to enter a lifeboat from the davits. Evans tried to get in but fumbled as she could not reach over the gunwale, deciding to stay on the boat to wait and board another collapsible lifeboat. Evans became one of only four First-Class women to perish in the disaster.

In the end, about 20 people were on board when it left the deck under the command of Quartermaster Arthur Bright.[113][114][95] Two First-Class passengers, Hugh Woolner and Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, jumped from A-Deck (which had started to flood) into the boat as it was being lowered, with Björnström-Stefansson landing upside down in the boat's bow and Woolner landing half-out, before being pulled aboard by the occupants.[115][65] Another First-Class passenger, Frederick Maxfield Hoyt, who had previously put his wife in the lifeboat, jumped in the water immediately after, and was hauled aboard by Woolner and Björnström-Steffansson.[114][115] The number of people on board later increased when 14 survivors, including R. Norris Williams and Rhoda Abbott, were transferred from Collapsible Boat A.[113][114] Carpathia picked up those aboard Collapsible Boat D at 7:15 A.M.[44]

- Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson

- Irene Wallach Harris, whose husband, theatre producer Henry, was lost.

- Eleanor Ileen Johnson

- Michel Marcel Navratil and his younger brother Edmond. Their father was lost.

Collapsible Engelhardt Lifeboat B (port)

By 2:10 A.M., Lightoller was struggling to retrieve Collapsible Boat B from the roof of the officers' quarters. He rigged up makeshift ramps from oars and spars down which he slid the boat onto the Boat Deck. Unfortunately, for all concerned, the boat broke through the ramp and landed upside-down on the deck.[116] There was no time to right it as Titanic began her final plunge. At 2:15 A.M., water swept across the Boat Deck, washing the upside-down lifeboat and many people into the sea.[117] Wireless operator Harold Bride found himself trapped underneath the overturned hull. Titanic's increasing angle in the water and an opening expansion joint caused the stays supporting the forward funnel to snap and crash into the water, crushing swimmers in its path and pushing Collapsible Boat B further away from the sinking ship.[118] As Titanic went under, the lifeboat was left in the midst of hundreds of people swimming in the water. Several dozen people climbed onto its hull, including Lightoller, who then took charge of it. Also aboard were Jack Thayer (whose mother was saved with her maid in Lifeboat 4, but whose father died), military historian Colonel Archibald Gracie, who later wrote a popular account of the disaster, and Chief Baker Charles Joughin. Bride managed to escape from the air pocket beneath the boat and made it onto the hull.[119]

Those aboard Collapsible Boat B suffered greatly during the night. The boat gradually sank lower into the water as the air pocket underneath it leaked away. The sea began to get up towards dawn, causing the lifeboat to rock in the swell and lose more of its air. Lightoller organised the men on the hull to stand in two parallel rows on either side of the centerline, facing the bow, and got them to sway in unison to counteract the rocking motion caused by the swell. They were directly exposed to the freezing seawater, first up to their feet, then to their ankles and finally to their knees as the boat subsided in the water. For some, the ordeal proved too much and one by one they collapsed, fell into the water and died. The victims included the Third-Class passenger David Livshin, whose body was taken to the Carpathia on the following morning. About 28 men were left alive by the morning and were transferred into other lifeboats before being rescued by Carpathia.[117]

- Wireless Operator Harold Bride

- Edward Arthur Dorking, an English immigrant

- Archibald Gracie IV, a military historian

- Chief Baker Charles John Joughin

- Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller (who took charge when he arrived)

- Jack Thayer, 17-year-old son of John B. Thayer, of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who was lost. Mrs. Thayer and her maid were rescued in Lifeboat 4.

According to Paul Lee, the Mackay Bennett, searching for bodies, saw Collapsible B on April 23, 1912, at 41°55' N, 49°20' W, and this should be the same as the life boat seen on May 16 by the Paul Paix, that reported a ship's lifeboat, clean, buttom up and without no visible damage, floating at position 41°51' N, 42°29' W.[120]

Collapsible Engelhardt Lifeboat A (starboard)

Collapsible Lifeboat A reached the deck the right way up and was being attached to the falls of No. 1 davits by Wilde, Murdoch and Moody when it was washed off Titanic at 2:15 A.M. First-Class passenger Edith Evans was seen running across the boat deck to try and board the lifeboat, having just given up her space in Collapsible Boat D. In the chaos, the canvas sides were not pulled up and the boat drifted away from the ship partially submerged and dangerously overloaded. Many of the occupants climbed in from the water but several died of hypothermia or fell back into the sea. Only about 14 people were left alive and the survivors were later rescued by Lifeboat 14 lead by Fifth Officer Lowe (who distributed his passengers among Lifeboats 4, 10, 12 and Collapsible D previously encountred to go back to the wreckage to save survivors). Some were transferred later to Collapsible D: among them were First-Class passenger R. Norris Williams, and Third-Class passenger Mrs. Rhoda Abbott, the only female aboard, who had lost her two young sons in the water. Three bodies, including that of Mr. Thomson Beattie, were left in Collapsible Boat A, which was allowed to drift off; they were not recovered until a month later, by RMS Oceanic, another vessel belonging to the White Star Line.[117]

Recovery and disposal of the lifeboats

Titanic's surviving passengers endured a cold night before being picked up by RMS Carpathia on the morning of 15 April. Lifeboat 2 was the first to be recovered, at 4:10 A.M., with Lifeboat 12 the last, at 8:15 A.M. Lifeboats 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 16 were brought aboard Carpathia, with the rest (including all four collapsible lifeboats) set adrift.[121] Collapsible Boat B was found again a few days later by the cable vessel Mackay-Bennett, but an attempt to bring it on board failed, and it was abandoned for good. Collapsible Boat A was later recovered by the White Star liner Oceanic along with three decomposing bodies and taken back to New York to be placed with the other lifeboats recovered by the Carpathia.[122]

The 13 lifeboats retrieved by Carpathia were taken to the White Star Line's Pier 59 in New York, where souvenir hunters soon stripped them of much of their equipment. The S.S. Titanic nameplates which were not already stolen were removed by White Star Line workmen along with the rest of the identification plaques, and the boats were then inventoried by the C.M. Lane Lifeboat Co. of Brooklyn.[123][124] They were assessed for salvage at a collective value of £930 ($4,972) as the only salvageable items recovered from Titanic. They remained in New York until at least December 1912; their whereabouts have been unknown since. One common misconception is that they may have been taken back to England aboard and installed on Olympic, Titanic's sister ship: however, this has since been disproven. They were either scrapped, left to rot in New York, or quietly redistributed to other vessels sometime after December 1912.[125]

Although nothing remains of the original lifeboats, some surviving fittings can still be seen, such as nameplates reading 'S.S. TITANIC'. Several are known to exist in museums and private collections, along with brass numbers, port plates reading 'LIVERPOOL', and house flags of the White Star Line, such as a burgee removed from the hull of one lifeboat by a souvenir hunter and now displayed in the museum of the Titanic Historical Society.[126] A full-size, accurate replica lifeboat is now on display at the maritime museum in Falmouth, England, and a less accurate one in Belfast at the Titanic Belfast visitor attraction.[127]

References

- ↑ "S.S. Titanic Lifeboat Plaque". Encyclopedia Titanica. 17 June 2004. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 110.

- 1 2 Gill 2010, p. 168.

- 1 2 3 Gill 2010, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Gill 2010, p. 171.

- 1 2 Gill 2010, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 4 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Beveridge & Hall 2011, p. 47.

- 1 2 Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 115.

- 1 2 Ward 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Marshall 1912, p. 141.

- 1 2 Berg, Chris (13 April 2012). "The Real Reason for the Tragedy of the Titanic". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 168.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 84.

- ↑ Gittins, Akers-Jordan & Behe 2011, p. 164.

- ↑ Ward 2012, p. 33.

- ↑ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, pp. 50–1.

- 1 2 Gill 2010, p. 173.

- ↑ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 29.

- 1 2 Mowbray 1912, p. 279.

- ↑ Aldridge 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 123.

- ↑ Cox 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 135.

- ↑ Lord 2005, p. 37.

- ↑ Barczewski 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 137.

- ↑ Barczewski 2011, p. 192.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 147.

- ↑ Bottomore 2000, p. 109.

- ↑ Wilson 2011, p. 244.

- ↑ Wilson 2011, p. 245.

- ↑ Wilson 2011, pp. 253–4.

- ↑ Wilson 2011, p. 256.

- 1 2 3 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 150.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 97.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 92.

- 1 2 Butler 1998, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Butler 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 144.

- 1 2 Butler 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 151.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 123.

- 1 2 Butler 1998, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Butler 1998, p. 100.

- 1 2 Bartlett 2011, p. 229.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 151.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 249.

- 1 2 Butler 1998, p. 144.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 110–1.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 167.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 147-8.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 148.

- ↑ Land of Enchantment (7 March 2014). "GFHC: Lady Zelig, Titanic Survivor". Daily Kos. Kos Media. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Jane Anne Rothschild: Titanic Survivor". Encyclopedia Titanica. 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2018. (ref: #250, updated 24 August 2017 11:27:01 AM)

- 1 2 3 4 Wormstedt & Fitch 2011, p. 139.

- ↑ "James Forward : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 122.

- ↑ Carla Christine Nielsine Andersen (Jensen);"Carla Christine Nielsine Andersen (Jensen): Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. 16 September 1998. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 155.

- ↑ "Ellen Mary Mockler : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ↑ Frederickssaid, David (19 June 2015). "Identifying Titanic stewardesses". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Mary Leather : Titanic Survivor". Eencyclopedia-titanica.org. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ "Annie Robinson : Titanic Survivor". www.encyclopedia-titanica.org. 16 December 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- 1 2 Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 154.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 145.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 154.

- ↑ Lord 2005, p. 151.

- ↑ "Death of Charles Williams". The Times. 6 December 1935. p. 6 – via Times Digital Archive.