The Imperial Japanese Navy (大日本帝国海軍) built four battlecruisers, with plans for an additional four, during the first decades of the 20th century. The battlecruiser was an outgrowth of the armoured cruiser concept, which had proved highly successful against the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Battle of Tsushima at the end of the Russo-Japanese War. In the aftermath, the Japanese immediately turned their focus to the two remaining rivals for imperial dominance in the Pacific Ocean: Britain and the United States.[1] Japanese naval planners calculated that in any conflict with the U.S. Navy, Japan would need a fleet at least 70 percent as strong as the United States' in order to emerge victorious. To that end, the concept of the Eight-Eight fleet was developed, where eight battleships and eight battlecruisers would form a cohesive battle line.[2] Similar to the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) and in contrast to the Royal Navy,[3] the Japanese envisioned and designed battlecruisers that could operate alongside more heavily armoured battleships to counter numerical superiority.[4]

The first phase of the Eight-Eight plan began in 1910, when the Diet of Japan authorised the construction of one battleship (Fusō) and four battlecruisers of the Kongō class. Designed by British naval architect George Thurston, the first of these battlecruisers (Kongō) was constructed in Britain by Vickers, while the remaining three were constructed in Japan. Armed with eight 14-inch (360 mm) guns and with a top speed of 30 knots (35 mph; 56 km/h), they were the most advanced capital ships of their time.[5] At the height of the First World War, an additional four battlecruisers of the Amagi class were ordered. The ships would have had a main battery of ten 16-inch (410 mm) guns, but none were ever completed as battlecruisers, as the Washington Naval Treaty limited the size of the navies of Japan, Britain and the United States.[6] Before the Second World War, a further class of two battlecruisers were planned (Design B-65), but more pressing naval priorities and a faltering war effort ensured these ships never reached the construction phase.[7]

Of the eight battlecruiser hulls laid down by Japan (the four Kongō and four Amagi class), none survived the Second World War. Amagi was being converted to an aircraft carrier when its hull was catastrophically damaged by the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923 and subsequently broken up, while the last two of the Amagi class were scrapped in 1924 according to the terms of the Washington Treaty.[6] Akagi was converted to an aircraft carrier in the 1920s, but was scuttled after suffering severe damage from air attacks during the Battle of Midway on 5 June 1942. The four Kongō-class ships were lost in action as well: two during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942,[8] one by American submarine in November 1944,[9] and one by American aircraft at Kure Naval Base in July 1945.[10]

Key

| Main guns | The number and type of the main battery guns |

| Armour | Thickness of the armoured belt |

| Displacement | Ship displacement at full combat load |

| Propulsion | Number of shafts, type of propulsion system, and top speed generated |

| Service | The dates work began and finished on the ship and its ultimate fate |

| Laid down | The date the keel began to be assembled |

| Commissioned | The date the ship was commissioned |

| Fate | The eventual fate of the ship (e.g., sunk, scrapped) |

Kongō class

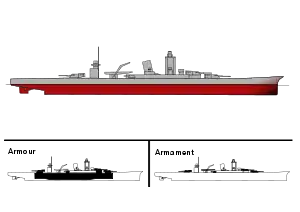

The four Kongō-class ships were the first battlecruisers ordered by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The four ships were authorised in 1910 as part of the Emergency Naval Expansion Bill, in response to the construction of HMS Invincible by the British Royal Navy.[11] Designed by British naval architect George Thurston, the first ship of the class (Kongō) was constructed in Britain by Vickers, with the remaining three built in Japan. They were armed with eight 14 in (356 mm) main guns, could sail at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), and were considered to "outclass all other [contemporary] ships".[5] Kongō was completed in August 1913, Hiei in August 1914, and Haruna and Kirishima in April 1915. The vessels saw minor patrol duty during the First World War.

In the aftermath of the Washington Naval Treaty, all four ships underwent extensive modernisation in the 1920s and 1930s, which reconfigured them as fast battleships.[12] The modernisations strengthened their armour, equipped them with seaplanes, overhauled their engine plant, and reconfigured their armament.[13] With a top speed of 30 kn (35 mph) and efficient engine plants, all four were active in the Second World War; Hiei and Kirishima sailed with the carrier strikeforce to attack Pearl Harbor, while Kongō and Haruna sailed with the Southern Force to invade Malaya and Singapore. Hiei and Kirishima were lost during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal,[14] Kongō was torpedoed on 21 November 1944 in the Formosa Strait,[9] and Haruna was sunk during the Bombing of Kure on 28 July 1945.[10]

| Ship | Main guns | Armour | Displacement | Propulsion | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Kongō | 8 × 14 in (356 mm)[5] | 8 in (203 mm)[15] | 27,500 long tons (27,941 t)[5] | 4 screws, steam turbines, 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) (later 30.5 kn (56.5 km/h; 35.1 mph))[16] | 17 January 1911 | 16 August 1913 | Torpedoed in the Formosa Strait, 21 November 1944[9] |

| Hiei | 4 November 1911 | 4 August 1914 | Scuttled following Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 13 November 1942[17] | ||||

| Kirishima | 17 March 1912 | 19 April 1915 | Sank following Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 15 November 1942[18] | ||||

| Haruna | 16 March 1912 | 19 April 1915 | Sunk by air attack, Kure Naval Base, 28 July 1945[18] | ||||

Amagi class

As part of the Eight-Eight fleet, four Amagi-class battlecruisers were planned. The order for these ships and four battleships of the Kii class put an enormous strain on the Japanese government, which by that time was spending a full third of its budget on the navy.[19] Akagi was the first ship to be laid down; construction began on 6 December 1920 at the naval yard in Kure. Amagi followed ten days later at the Yokosuka naval yard. Atago's keel was laid in Kobe at the Kawasaki shipyard on 22 November 1921, while Takao, the fourth and final ship of the class, was laid down at the Mitsubishi shipyard in Nagasaki on 19 December 1921.[6]

The terms of the February 1922 Washington Naval Treaty forced the class' cancellation, but the two closest to completion (Amagi and Akagi) were saved from the scrappers by a provision that allowed two capital ships to be converted to aircraft carriers. However, the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake caused significant stress damage to the hull of Amagi. The structure was too heavily damaged to be usable, and conversion work was abandoned.[20][N 1] Amagi was struck from the navy list and sold for scrapping, which began on 14 April 1924. The other two ships, Atago and Takao, were officially cancelled two years later (31 July 1924) and were broken up for scrap in their slipways. Akagi went on as an aircraft carrier to fight in the Second World War, where it was sunk after air attack during the Battle of Midway.[6]

| Ship | Main guns | Armour | Displacement | Propulsion | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Amagi | 10 × 16 in (406 mm)[6] | 10 in (254 mm)[6] | 46,000 long tons (46,738 t)[6] | 4 screws, steam turbines, 30 kn (56 km/h; 35 mph)[6] | 16 December 1920 | November 1923 (projected) | Reordered as aircraft carrier; damaged in earthquake; cancelled and scrapped[6] |

| Akagi | 6 December 1920 | December 1923 | Reordered and completed as aircraft carrier[6] | ||||

| Atago | 22 November 1921 | December 1924 | Cancelled and scrapped[6] | ||||

| Takao | 19 December 1921 | December 1924 | Cancelled and scrapped[6] | ||||

Design B-64/B-65 class

Design B-64 was originally intended to be part of Japan's Night Battle Force, a force that would attack an enemy fleet's outer defence ring of cruisers and destroyers under the cover of darkness. After penetrating the ring, Japanese cruisers and destroyers would launch torpedo attacks on the enemy's battleships. The remainder of the enemy would be finished off by the main fleet on the following day. The B-64s were intended to support the lighter cruisers and destroyers in these nighttime strikes.[21] This strategy was altered when the Japanese learned the specifications of the United States' Alaska-class large cruisers. The design was enlarged and redesignated B-65; their purpose would now be to screen the main battle fleet against the threat posed by the fast and heavily armed Alaskas.[22][23] With war looming in 1940, the Japanese focused on more useful and versatile ship types such as aircraft carriers and cruisers; the Japanese defeat at the 1942 Battle of Midway meant that the ships were postponed indefinitely, and with more important strategic considerations to worry about, the ships were never built.[24][25]

| Ship | Main guns | Armour | Displacement | Propulsion | Service | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laid down | Commissioned | Fate | |||||

| Yard number 795 (not named)[N 2] | 9 × 12.2 in (310 mm)[26] | 7.5 in (191 mm)[26] | 34,000 long tons (35,000 t)[26] | Four sets of geared steam turbines, 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph)[26] | NA | 1945 (projected) | Not ordered due to war |

| Yard number 796 (not named) | 1946 (projected) | ||||||

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Stille, p. 4

- ↑ Stille, p. 7

- ↑ Staff, p. 3

- ↑ Evans & Peattie, p. 150

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson, p. 48

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gardiner and Gray, p. 235

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, p. 360

- ↑ Jackson, p. 121

- 1 2 3 Wheeler, p. 183

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 129

- ↑ Gardiner and Gray, p. 234

- ↑ Stille, p. 16

- ↑ Stille, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Stille, p. 19

- ↑ McCurtie, p. 185

- ↑ Stille, p. 15

- ↑ Schom, p. 417

- 1 2 Stille, p. 20

- ↑ Gardiner and Gray, p. 224

- 1 2 Stille, p. 8

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, pp. 273–276

- ↑ Lacroix and Wells II, p. 606

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, pp. 359–360

- ↑ Lacroix and Wells II, p. 829

- ↑ Garzke and Dulin, pp. 84–85

- 1 2 3 4 5 Garzke and Dulin, p. 86

Bibliography

- Evans, David C. & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-101-3.

- Jackson, Robert (2000). The World's Great Battleships. Brown Books. ISBN 1-897884-60-5

- Lacroix, Eric; Wells, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- McCurtie, Francis (1989) [1945]. Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. London: Bracken Books. ISBN 1-85170-194-X

- Schom, Alan (2004). The Eagle and the Rising Sun; The Japanese-American War, 1941–1943. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393049248

- Stille, Mark (2008). Imperial Japanese Navy Battleship 1941–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-280-6

- Wheeler, Keith (1980). War Under the Pacific. New York: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-3376-1.