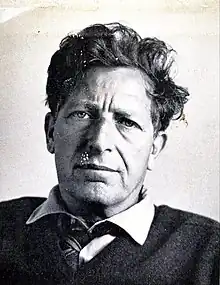

Prior to his career in social criticism, the American writer Paul Goodman had a prolific career in avant-garde literature, including some 16 works for the stage. His plays, mostly written in the 1940s, were typically experimental. Their professional productions were either unsuccessful or flopped, including the three productions staged with The Living Theatre in the 1950s and one with The American Place Theatre in 1966. His lack of recognition as a litterateur in the 1950s helped drive him to his successful career in social criticism in the 1960s.

Background

Paul Goodman's writing career was prolific and heterogeneous.[1] Though primarily known for his 1960s works of social criticism,[1] Goodman primarily thought of himself as an artist–humanist, or man of letters.[2] Across all of his works, he said he had one subject, "the organism and the environment", and one common, pragmatic aim, that his writing should effect a change.[1][2] Up to the 1950s, he wrote literary avant-garde fiction, poetry, and theater,[3] typically experimental.[4][5] While his fiction and poetry received some critical response,[1] he was largely unrecognized as a litterateur, apart from a coterie of admirers. His difficult personality and unrefined style hindered his literary reputation.[6][7] This dissatisfaction from lack of audience in the 1950s is what drew him to social criticism in the 1960s, where he found success, leaving behind his literary ambitions for the limelight.[1][3]

Noh plays

In what he intended to be an American adaptation of the Japanese Noh art form,[8] Goodman wrote five verse drama plays, or what Goodman called "dance poems": Dusk, The Birthday, The Three Disciplines, The Cyclist, and The Stop Light.[9] In his adaptation, he portrayed the three Noh characters—the Waki, the Shite, and the Chorus—respectively as the "Audience", the "Object of Awareness", and the "Mind of the Poet Himself".[8] Put another way, the plays each have three characters: a traveler (the audience), a spirit (the idea of the poem), and the chorus (that interprets both for each other).[10]

His friend's small press, 5x8 Press, published the collection as Stop-Light in December 1941.[11] It was Goodman's first book,[12] and included an essay on the art form by Goodman and illustrations by his brother, Percival.[9] Dusk had been published separately in a periodical two months prior to the book, and The Birthday would be revised and published in Michael Benedikt's 1967 anthology Theatre Experiment.[9]

Dudley Fitts, contemporaneously reviewing the five American Noh plays in The Saturday Review of Literature, wrote that only The Three Disciplines and The Stop Light achieved the author's intentions but even then, the form did not adapt well outside of its original language and tradition. He also judged Goodman's diction as generally flat and humor as informal. The other three "failures", wrote Fitts, portrayed their protagonist (the Object of Awareness) as "either a dismal truism ... or a downright silliness". The Stop Light, however, moved Fitts, and in his opinion successfully integrated Goodman's idea, symbol, and diction.[8] The New Republic considered Goodman's conceit clever and strategic but found that his themes did not neatly resolve.[10]

The New York Poets' Theater produced Dusk and Stop Light in May 1948. Artist Mark Rothko designed Dusk's set and Ned Rorem composed its music, while Costantino Nivola designed Stop Light's set and Ben Weber composed its music.[13] The Noh plays were later staged at New York's CHARAS Theater in 1990.[14]

The Living Theatre

Goodman's interest in theater developed alongside Julian Beck, Judith Malina, and their Living Theatre.[15] After being introduced by playwright Tennessee Williams,[16] Goodman became a close and influential friend, introducing Malina and Beck to anarchism prior to their founding of their Living Theatre.[17] Goodman described himself as "a kind of company psychiatrist" for the theater company, for which he also wrote plays that the theater considered among the American vanguard. In turn, Goodman wrote in defense of the Living Theatre. Director Lawrence Kornfeld said Goodman's plays were among the first to incorporate non-linguistic elements, such as screams and other sounds.[15]

As Malina and Beck prepared to open The Living Theatre in New York's Cherry Lane Theatre, they held their first show in their living room over a week in late August 1951. Among their five-play program was Goodman's short farce Childish Jokes: Crying Backstage.[18] The sets and invitations were primitive and the 20-person seating arrangements intimate. Attendees included John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Carl Van Vechten.[19]

Faustina

Goodman's Faustina centers on Faustina the Younger, the wife of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and reflects on Aurelius's Meditations with Reichian themes. Faustina falls in love with the gladiator Galba, who is killed in a ritual ceremony to ease her jealousy. The play ends with the scenery collapsing, representing the fall of Roman civilization. In a closing monologue, Faustina breaks the fourth wall to chastize the audience for not having risen onto the stage to prevent Galba's murder,[20] or to express any other spontaneous thought of the actor.[21]

Written in 1948,[22][23] Jackson Mac Low and members of the Resistance group first produced Faustina with no stage to a full house in Robert Motherwell's New York City East Village loft in June 1949.[24][25] Malina and Beck attended.[25] Their Living Theatre would produce the show three years later, in May 1952, in New York's Cherry Lane Theatre.[26] Goodman published a revised edition in the Quarterly Review of Literature (1961) and further revised for publication among his Three Plays (1965).[22]

The Living Theatre selected Goodman's Faustina to put on as one of their first three shows in the Cherry Lane Theatre,[19] staged around the 1951 holiday season.[19] Faustina followed productions of Gertrude Stein's Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights and Kenneth Rexroth's Beyond the Mountains, which sold out and flopped, respectively.[27] A set of sullen January 1952 rehearsals for Faustina led to its production's postponement. Beck continued to design Faustina's Roman frescos with funds from a successful program of bohemian theater. Faustina rehearsals resumed in April and were complicated as the theater bled into their personal lives, including a love triangle between Malina, Goodman, and a lover of Malina's who appeared in Faustina. The lover's Gestalt therapy sessions with Goodman had turned into an affair, sometimes delaying rehearsals.[28] The Living Theatre's production was hurt by its actors lack of faith in its ending, in which Julie Bovasso, who played Faustina, struggled to give the closing, spontaneous monologue.[29] On opening night, her speech consisted of her annoyance at the prompt, which she considered pretentious. Goodman approved of her authenticity.[30] After Bovasso quit the production, another cast member gave the speech instead. Similar calls to direct action would feature in the troupe's performances by the end of the 1960s, but Beck himself later came to consider this specific monologue prompt insulting to the audience.[29]

The show opened in late May 1952 to mediocre reviews and scarce attendance. Critics considered Beck's collaged set design to be a highlight. They considered Goodman's writing and the troupe's acting to be less effective.[29] A New York Times reviewer described the first act of the Living Theatre production as "numb".[31] Though the show continued through mid-June, Bovasso left after several performances. As Beck put it, the production was "humiliating agony".[32]

The Young Disciple

The Young Disciple, a free interpretation of the Gospel of Mark,[33] follows a pseudobiblical plot in which a community attempts to interpret a "miraculous event" that is never specifically explained but comes to interfere with their daily lives and hampers their creativity.[34] The play explores blocked psychological development and the natural human capacity to act freely, as Goodman later expressed in his book on Gestalt therapy.[35]

Originally written by Goodman in 1941,[22] he pressed the theatre in early 1955 to produce it.[36] By mid-year, Beck began to cast and stage the play with choreography by Merce Cunningham[37] and music by Ned Rorem.[38] Beck, the play's director,[34] designed a set of painted collages on corrugated cardboard. Personal issues again complicated the production, as Beck sought to please Goodman by producing the play but was privately insecure as to whether Goodman liked him.[39] The play itself, as the writer John Tytell put it, was a "fulfillment of Goodman's own Socratic fantasy ... that he could advise youth on how to live in a disintegrating universe".[33] Goodman saw his role as liberating the audience from an unspecific societal influence that alienated them from their personhood and made them obedient. In this play, this manifested as emotional outbursts, crawling on the ground while "making night noises, strange husky grating and chirping sounds", heavy breathing, vomiting, dancing, and trembling. In the week before the show's opening, New York police questioned cast members and inferred that the play's content could be deemed obscene. They ultimately did not stop the show.[35]

Staged in an Upper West Side loft,[26] the production came during an artistic period of the Living Theatre in which they did not advertise, charge admission, or invite critics. Despite Beck considering The Young Disciple as their loft period's high point,[34] it proved unpopular upon its October 1955 opening,[33] as affronted audiences reacted to its charged contents in disgust, annoyance, terror, awe, and excitement, according to Beck.[35] Beck now believed that the Living Theatre had become too arty and focused on its artistic community rather than on the theatre itself.[33] Goodman later published The Young Disciple in his Three Plays (1965).[22]

The Cave at Machpelah

For two decades, beginning in 1935, Goodman worked on The Cave at Machpelah, a verse drama based on Abraham's biblical sacrifice of Isaac.[40] Goodman used the play to explore the combined origins of Arab and Jewish peoples,[41] man's relationship with God, and the issue of "faith" as discussed in Kierkegaard's philosophical work Fear and Trembling.[42] Completed in 1958, Goodman called this trilogy "The Abraham Plays".[43] Act I, Abraham and Isaac (1935), is a poetic retelling of the sacrifice of Isaac and the test of Abraham's faith. Act II, Hagar and Ishmael (1935), has Ishmael quarrel with the Angel of the Lord. In Act III, The Cave at Machpelah (1958), Ishmael and Isaac arrange to bury Abraham.[44] The third act was published in Commentary in June 1958.[45]

Beck began directing and rehearsing the play during early 1959.[46] The production included music by Ned Rorem and choreography by Merce Cunningham.[47] The Living Theatre rehearsed the work for ten weeks. The production was marred by delays, threats of bankruptcy, and other technical issues.[41] The Living Theatre opened The Cave at Machpelah at the end of June 1959 at their Sixth Avenue & 14th Street theater.[42] It flopped, closing in July after seven performances. Malina was uncomfortable in her role as Sarah and Beck felt that the other actors could not match the play's complexity. Critics panned the play as being moralistic, too philosophical, and untheatrical.[41] Its New York Daily News reviewer found it hard to follow, apart from its love triangle between Abraham, his wife Sarah, and her handmaiden slave Hagar.[42] The New York Times wrote that Goodman got "lost in his dramatic structure" through the middle of the play, as if he lost interest, and despite some moments of majesty and inspiration ultimately did not accomplish the ideals Goodman had intended.[47]

Jonah

Originally written circa 1942, Jonah, subtitled "a biblical comedy with Jewish jokes culled far and wide",[48] focuses on the biblical Jonah's life after escaping from the whale. The Angel of the Lord tells a reluctant Jonah to warn the city of Nineveh of its impending destruction. Jonah dallies and ends up inside a whale on a sea voyage. He escapes and completes his task, and the citizens of Nineveh repent and save the city. Feeling fooled, Jonah reprimands God, who imparts a lesson of forbearance.[49]

Goodman first published the play in his 1945 fiction collection The Facts of Life.[48] Composer Jack Beeson worked the play into a three-act opera libretto during his Rome Prize years (1948–1950),[50] which went unpublished[51] and unproduced.[52][53] Jackson Mac Low and the "Prester John's Company" planned a production of Goodman's Jonah for June 1950.[24] Goodman revised the play in 1955 and reprinted Jonah in his 1965 collection Three Plays. The American Place Theatre produced the play in February 1966[48] as a two-act musical with vaudeville stylings of his contemporaneous Jewish culture in New York City.[54]

The 1966 American Place Theatre production, in Hell's Kitchen, New York City, ran for 24 performances. It was directed by Lawrence Kornfeld, scored by Meyer Kupferman, with scenic design and choreography by Remy Charlip and lighting by Roger Morgan.[55][49] The production reproduced much of the literal detail of the Book of Jonah.[56] As a "musical experiment in the dramatic field", Kupferman's score played throughout the performance, either as a focal song or dance, or as background music.[57] The performance's 30 cast members,[57] which included Earle Hyman and Sorrell Booke,[49] spoke in a Yiddish accent[57] and used Yiddishisms.[6] Jonah is played as a stereotypical Jewish elder "philosopher-schlemiel", a pragmatic yet rebellious servant both defying God and ironically yielding to him. As one reviewer put it, Jonah has "the dilemma of the modern moralist who finds his message diluted by ready and uncritical acceptance and whose act of rebellion is rendered impotent by a public which embraces novelty in any form", making the rebel into a kind of clown.[56] One critic would note autobiographical allusions between Goodman (the playwright and prominent social gadfly) and his character Jonah.[49]

Critics responded negatively.[58] Goodman's attempt to convert the Book of Jonah into a modern parable was incomplete, wrote the Congress Bi-Weekly.[56] Reviewing for The New York Times, Stanley Kaufmann found the play inconsistent, with some charm and imagination that did not last throughout, and poorly executed satire.[49] Wilfrid Sheed of Commonweal declared the first act "hopeless", having overused resignation humor of shrugs and mumbles.[59] To The New Yorker's Edith Oliver, the play was an "untheatrical ... slovenly bore" whose comedy and dramatization did not land.[60] The worst part of the playwright's "self-indulgence and confused medley of styles and purposes", continued Congress Bi-Weekly, was how the prophet-hero lacked clarity of purpose and attempted to convey Goodman's oversimplistic maxim that comic outsiders are society's sole truth-speakers.[56] Critics compared Jonah's approach with other modern takes on Old Testament themes, such as The Flowering Peach[49] and The Green Pastures.[59]

Cubist plays

Goodman wrote and published four "Cubist plays" to demonstrate his theory of literary structure from his 1954 book of literary criticism, The Structure of Literature. He called them "Cubist" due to his intention of abstracting the plays' plots from their structures, so that individual characters became archetypal embodiments of types of plots.[61] The first three plays reference Greek tragedians: Structure of Tragedy, after Aeschylus; Structure of Tragedy, after Sophocles; and Structure of Pathos, after Euripides. Goodman's plays were meant to address structural elements of each: the austerity of Aeschylus, the ironic and psychological elements of Sophocles, and the existential pain and fate in Euripides. The fourth play, Little Hero, after Molière, follows tragic nobility, referencing the 17th-century French satirist, though a review said it had more in common with farce like Ubu Roi. The plays consist of a range of style and diction, including both the high style of the period as well as contemporaneous colloquialisms.[61]

The theoretical basis of the plays came from Goodman's dissertation, The Formal Analysis of Poems, which he finished in 1940, but did not publish until 1954 (as The Structure of Literature) when he received his humanities Ph.D.[62] He initially published the first three plays in early 1950 in the Quarterly Review of Literature. They were revised and republished in a small print run in 1970 as Tragedy & Comedy: Four Cubist Plays.[63] Poet Macha Rosenthal, in his Poetry magazine review, praised the originality of the Cubist plays as "modern lyric-contemplative poems in dramatic guise" and said that their emotional saturation and immediacy belied their intellectual pretext.[61]

Known productions

- Dusk and Stop Light, The Poets' Theater, New York City Upper East Side, May 1948[13]

- Faustina, Jackson Mac Low and members of the Resistance group, New York City East Village loft, June 1949[24]

- Jonah, Prester John's Company (Jackson Mac Low), New York City, June 1950, presumed[24]

- Childish Jokes: Crying Backstage, The Living Theatre, New York City, August 1951[64]

- Faustina, The Living Theatre, Cherry Lane Theatre, New York City, May–June 1952[32]

- The Young Disciple, The Living Theatre, New York City, October 1955[33]

- The Cave at Machpelah, The Living Theatre, New York City, June–July 1959[65][41]

- Jonah, American Place Theater, New York City, February–March 1966[66]

- Stop-Light: Five Noh Plays, CHARAS Theater, New York City, December 1990[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith 2001, p. 178.

- 1 2 Kostelanetz 1969, p. 271.

- 1 2 Mattson 2002, p. 110.

- ↑ Mattson 2002, p. 105: "In certain ways, the editors of the Partisan Review embraced avant-garde literary innovation on an intellectual level, but Goodman lived and practiced it. Both his anarcho-pacifism and his literary experimentalism made the editors at Partisan Review squeamish."

- ↑ Rogoff 1997, p. 135.

- 1 2 Rogoff 1997, p. 136.

- ↑ Mattson 2002, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Fitts 1942.

- 1 2 3 Nicely 1979, pp. 20–23.

- 1 2 Frankenberg 1942.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 3.

- 1 2 "The Poets' Theater". Partisan Review. Vol. 15, no. 5. p. 595. ISSN 0031-2525.

- 1 2 Clarkson, Petruska; Mackewn, Jennifer (1993). Fritz Perls. Sage. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4462-2456-4.

- 1 2 Kostelanetz 1969, p. 284.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 Tytell 1995, p. 72.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, pp. 46, 82–83.

- ↑ Bottoms, Stephen J. (2004). Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960s Off-Off-Broadway Movement. University of Michigan Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-472-02221-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Nicely 1979, p. 104.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 Nicely 1979, p. 261.

- 1 2 Tytell 1995, p. 53.

- 1 2 Nicely 1979, p. 249.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, pp. 79–83.

- 1 2 3 Tytell 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Bottoms 2004, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Shanley 1952.

- 1 2 Tytell 1995, pp. 83–84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tytell 1995, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 Antliff 2017, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Antliff 2017, p. 148.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 112.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 117.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 182.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 118.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, pp. 153–154.

- 1 2 3 4 Tytell 1995, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 McHarry 1959.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 143.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 143; Rogoff 1997, p. 136.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 64.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 153.

- 1 2 Funke 1959.

- 1 2 3 Nicely 1979, pp. 32, 104.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kauffmann 1966.

- ↑ Brody, Martin (2014). "A History of the Rome Prize in Music Composition". Music and Musical Composition at the American Academy in Rome. Boydell & Brewer. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-58046-245-7.

- ↑ Freeman, John W. (1984). "Jack Beeson". The Metropolitan Opera Stories of the Great Operas. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-393-04051-7.

- ↑ Greene, David Mason (1985). Greene's Biographical Encyclopedia of Composers. Collins. p. 1292. ISBN 978-0-00-434363-1.

- ↑ Duffie, Bruce (December 2015). "Historic Interviews: composer Jack Beeson". Opera Journal. 48 (4): 35–66. ISSN 0030-3585. ProQuest 1764121215.

The first opera I wrote, Jonah, was written [without a hope of performance], and has actually never been performed.

- ↑ Dietz, Dan (2010). "Jonah (Meyer Kupferman; 1966)". Off Broadway Musicals, 1910–2007. McFarland. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7864-5731-1.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 Hochman 1966.

- 1 2 3 Zolotow 1965.

- ↑

- Kauffmann 1966 (The New York Times): "It adds up to what may be called a non-wasted evening, rather than satisfactory one."

- Oliver 1966 (The New Yorker): "Jonah, it is my sad duty to report, is a slovenly bore."

- Sheed 1966 (Commonweal): "The first act is pretty hopeless" ... "is hardly worth the effort" ... "if you like this sort of thing, well, this is the sort of thing you like."

- Hochman 1966 (Congress Bi-Weekly): "its latest play ... falls short of the mark despite its high aims", "It founders under the weight of bright ideas dimly realized." "Goodman's Jonah is a beached whale, victim of its author's self-indulgence and confused medley of styles and purposes."

- Gottfried 1968, p. 74: "The entire business was effete, amateurish"

- 1 2 Sheed 1966.

- ↑ Oliver 1966.

- 1 2 3 Rosenthal 1971.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 57.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, pp. 46, 148.

- ↑ Tytell 1995, p. 71; Nicely 1986, p. 156.

- ↑ Nicely 1979, p. 349.

- ↑ Peterson, Bernard L. Jr. (1993). "Jonah". A Century of Musicals in Black and White: An Encyclopedia of Musical Stage Works By, About, or Involving African Americans. Greenwood Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-313-06454-8.

Bibliography

- Antliff, Allan (2017). "Poetic Tension: The Aesthetic Politics of the Living Theatre". In Goyens, Tom (ed.). Radical Gotham: Anarchism in New York City from Schwab's Saloon to Occupy Wall Street. University of Illinois Press. pp. 142–160. doi:10.5406/j.ctv4ncnpj.10. ISBN 978-0-252-04105-1. JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctv4ncnpj.10. Previously published as "Poetic Tension, Aesthetic Cruelty: Paul Goodman, Antonin Artaud, and the Living Theatre". Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies (1 & 2). 2015. ISSN 1923-5615.

- Fitts, Dudley (April 25, 1942). "Questions and Gambols (Rev. of Stop-Light)". The Saturday Review of Literature. Vol. 25, no. 17. p. 13. ISSN 0036-4983.

- Frankenberg, Lloyd (March 16, 1942). "Poems Real and Surreal (Rev. of Stop-Light)". The New Republic. Vol. 106, no. 11. p. 371. ISSN 0028-6583.

- Funke, Lewis (July 1, 1959). "Off-Broadway: Bible Tale; 'Cave at Machpelah' Is Story of Abraham". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Gottfried, Martin (1968). A Theater Divided: The Postwar American Stage. Little, Brown. pp. 73–74. OCLC 923840.

- Hochman, Baruch (March 7, 1966). "A Whale of a Jonah". Congress Bi-Weekly. Vol. 33. p. 19. OCLC 3477442.

- Kauffmann, Stanley (February 16, 1966). "Theater: Paul Goodman Examines Story of Jonah; Sorrell Booke Starred in the Title Role Work Appears Partly Autobiographical". The New York Times. p. 52. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Kostelanetz, Richard (1969). "Paul Goodman: Persistence and Prevalence". Master Minds: Portraits of Contemporary American Artists and Intellectuals. Macmillan. pp. 270–288. OCLC 23458.

- Mattson, Kevin (2002). "Paul Goodman, Anarchist Reformer: The Politics of Decentralization". Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945–1970. Penn State University Press. pp. 97–144. ISBN 978-0-271-05428-5. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctt7v4k3.

- McHarry, Charles (July 1, 1959). "Fails to Dig Contents of Downtown 'Cave' (Rev. of The Cave at Machpelah)". New York Daily News. p. 64. ISSN 2692-1251.

- Nicely, Tom (1979). Adam and His Work: A Bibliography of Sources by and about Paul Goodman (1911–1972). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1219-2. OCLC 4832535.

- — (1986). "Adam and His Work: A Bibliographical Update". In Parisi, Peter (ed.). Artist of the Actual: Essays on Paul Goodman. Scarecrow Press. pp. 153–183. ISBN 978-0-8108-1843-9. OCLC 12418868.

- Oliver, Edith (February 26, 1966). "The Theatre: Off Broadway (Rev. of Jonah)". The New Yorker. Vol. 42, no. 1. pp. 71–72. ISSN 0028-792X.

- Rogoff, Leonard (1997). "Paul Goodman". In Shatzky, Joel; Taub, Michael (eds.). Contemporary Jewish-American Novelists: A Bio-critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Press. pp. 128–139. ISBN 978-0-313-29462-4. OCLC 35758115.

- Rosenthal, M. L. (1971). "Plastic Possibilities". Poetry. Vol. 119, no. 2. pp. 99–104. ISSN 0032-2032. JSTOR 20595405.

- Shanley, Jack P. (May 26, 1952). "The Theatre: Make Mine Hashish (Rev. of Faustina)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Sheed, Wilfrid (March 18, 1966). "The Stage". Commonweal. Vol. 83, no. 23. p. 699. ISSN 0010-3330.

- Smith, Ernest J. (2001). "Paul Goodman". In Hansom, Paul (ed.). Twentieth-Century American Cultural Theorists. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 246. pp. 177–189. ISBN 0-7876-4663-6. Gale MZRHFV506143794.

- Tytell, John (1995). The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1558-4.

- Widmer, Kingsley (1980). Paul Goodman. Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-7292-8.

- Zolotow, Sam (December 8, 1965). "Music and Drama to Meld in 'Jonah'; American Place Theater to Give Play in February". The New York Times. p. 56. ISSN 0362-4331.