In electrical engineering and computer science, Lloyd's algorithm, also known as Voronoi iteration or relaxation, is an algorithm named after Stuart P. Lloyd for finding evenly spaced sets of points in subsets of Euclidean spaces and partitions of these subsets into well-shaped and uniformly sized convex cells.[1] Like the closely related k-means clustering algorithm, it repeatedly finds the centroid of each set in the partition and then re-partitions the input according to which of these centroids is closest. In this setting, the mean operation is an integral over a region of space, and the nearest centroid operation results in Voronoi diagrams.

Although the algorithm may be applied most directly to the Euclidean plane, similar algorithms may also be applied to higher-dimensional spaces or to spaces with other non-Euclidean metrics. Lloyd's algorithm can be used to construct close approximations to centroidal Voronoi tessellations of the input,[2] which can be used for quantization, dithering, and stippling. Other applications of Lloyd's algorithm include smoothing of triangle meshes in the finite element method.

History

The algorithm was first proposed by Stuart P. Lloyd of Bell Labs in 1957 as a technique for pulse-code modulation. Lloyd's work became widely circulated but remained unpublished until 1982.[1] A similar algorithm was developed independently by Joel Max and published in 1960,[3] which is why the algorithm is sometimes referred as the Lloyd-Max algorithm.

Algorithm description

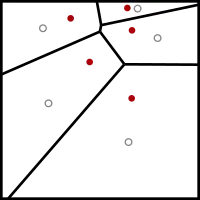

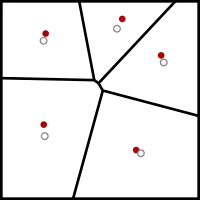

Lloyd's algorithm starts by an initial placement of some number k of point sites in the input domain. In mesh-smoothing applications, these would be the vertices of the mesh to be smoothed; in other applications they may be placed at random or by intersecting a uniform triangular mesh of the appropriate size with the input domain.

It then repeatedly executes the following relaxation step:

- The Voronoi diagram of the k sites is computed.

- Each cell of the Voronoi diagram is integrated, and the centroid is computed.

- Each site is then moved to the centroid of its Voronoi cell.

Integration and centroid computation

Because Voronoi diagram construction algorithms can be highly non-trivial, especially for inputs of dimension higher than two, the steps of calculating this diagram and finding the exact centroids of its cells may be replaced by an approximation.

Approximation

A common simplification is to employ a suitable discretization of space like a fine pixel-grid, e.g. the texture buffer in graphics hardware. Cells are materialized as pixels, labeled with their corresponding site-ID. A cell's new center is approximated by averaging the positions of all pixels assigned with the same label. Alternatively, Monte Carlo methods may be used, in which random sample points are generated according to some fixed underlying probability distribution, assigned to the closest site, and averaged to approximate the centroid for each site.

Exact computation

Although embedding in other spaces is also possible, this elaboration assumes Euclidean space using the L2 norm and discusses the two most relevant scenarios, which are two, and respectively three dimensions.

Since a Voronoi cell is of convex shape and always encloses its site, there exist trivial decompositions into easy integratable simplices:

- In two dimensions, the edges of the polygonal cell are connected with its site, creating an umbrella-shaped set of triangles.

- In three dimensions, the cell is enclosed by several planar polygons which have to be triangulated first:

- Compute a center for the polygon face, e.g. the average of all its vertices.

- Connecting the vertices of a polygon face with its center gives a planar umbrella-shaped triangulation.

- Trivially, a set of tetrahedra is obtained by connecting triangles of the cell's hull with the cell's site.

Integration of a cell and computation of its centroid (center of mass) is now given as a weighted combination of its simplices' centroids (in the following called ).

- Two dimensions:

- For a triangle the centroid can be easily computed, e.g. using cartesian coordinates.

- Weighting computes as simplex-to-cell area ratios.

- Three dimensions:

- The centroid of a tetrahedron is found as the intersection of three bisector planes and can be expressed as a matrix-vector product.

- Weighting computes as simplex-to-cell volume ratios.

For a 2D cell with n triangular simplices and an accumulated area (where is the area of a triangle simplex), the new cell centroid computes as:

Analogously, for a 3D cell with a volume of (where is the volume of a tetrahedron simplex), the centroid computes as:

Convergence

Each time a relaxation step is performed, the points are left in a slightly more even distribution: closely spaced points move farther apart, and widely spaced points move closer together. In one dimension, this algorithm has been shown to converge to a centroidal Voronoi diagram, also named a centroidal Voronoi tessellation.[4] In higher dimensions, some slightly weaker convergence results are known.[5][6]

The algorithm converges slowly or, due to limitations in numerical precision, may not converge. Therefore, real-world applications of Lloyd's algorithm typically stop once the distribution is "good enough." One common termination criterion is to stop when the maximum distance moved by any site in an iteration falls below a preset threshold. Convergence can be accelerated by over-relaxing the points, which is done by moving each point ω times the distance to the center of mass, typically using a value slightly less than 2 for ω.[7]

Applications

Lloyd's method was originally used for scalar quantization, but it is clear that the method extends for vector quantization as well. As such, it is extensively used in data compression techniques in information theory. Lloyd's method is used in computer graphics because the resulting distribution has blue noise characteristics (see also Colors of noise), meaning there are few low-frequency components that could be interpreted as artifacts. It is particularly well-suited to picking sample positions for dithering. Lloyd's algorithm is also used to generate dot drawings in the style of stippling.[8] In this application, the centroids can be weighted based on a reference image to produce stipple illustrations matching an input image.[9]

In the finite element method, an input domain with a complex geometry is partitioned into elements with simpler shapes; for instance, two-dimensional domains (either subsets of the Euclidean plane or surfaces in three dimensions) are often partitioned into triangles. It is important for the convergence of the finite element methods that these elements be well shaped; in the case of triangles, often elements that are nearly equilateral triangles are preferred. Lloyd's algorithm can be used to smooth a mesh generated by some other algorithm, moving its vertices and changing the connection pattern among its elements in order to produce triangles that are more closely equilateral.[10] These applications typically use a smaller number of iterations of Lloyd's algorithm, stopping it to convergence, in order to preserve other features of the mesh such as differences in element size in different parts of the mesh. In contrast to a different smoothing method, Laplacian smoothing (in which mesh vertices are moved to the average of their neighbors' positions), Lloyd's algorithm can change the topology of the mesh, leading to more nearly equilateral elements as well as avoiding the problems with tangling that can arise with Laplacian smoothing. However, Laplacian smoothing can be applied more generally to meshes with non-triangular elements.

Different distances

Lloyd's algorithm is usually used in a Euclidean space. The Euclidean distance plays two roles in the algorithm: it is used to define the Voronoi cells, but it also corresponds to the choice of the centroid as the representative point of each cell, since the centroid is the point that minimizes the average squared Euclidean distance to the points in its cell. Alternative distances, and alternative central points than the centroid, may be used instead. For example, Hausner (2001) used a variant of the Manhattan metric (with locally varying orientations) to find a tiling of an image by approximately square tiles whose orientation aligns with features of an image, which he used to simulate the construction of tiled mosaics.[11] In this application, despite varying the metric, Hausner continued to use centroids as the representative points of their Voronoi cells. However, for metrics that differ more significantly from Euclidean, it may be appropriate to choose the minimizer of average squared distance as the representative point, in place of the centroid.[12]

See also

- The Linde–Buzo–Gray algorithm, a generalization of this algorithm for vector quantization

- Farthest-first traversal, a different method for generating evenly spaced points in geometric spaces

- Mean shift, a related method for finding maxima of a density function

- K-means++

References

- 1 2 Lloyd, Stuart P. (1982), "Least squares quantization in PCM", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 28 (2): 129–137, doi:10.1109/TIT.1982.1056489, S2CID 10833328.

- ↑ Du, Qiang; Faber, Vance; Gunzburger, Max (1999), "Centroidal Voronoi tessellations: applications and algorithms", SIAM Review, 41 (4): 637–676, Bibcode:1999SIAMR..41..637D, doi:10.1137/S0036144599352836.

- ↑ Max, Joel (1960), "Quantizing for minimum distortion", IRE Transactions on Information Theory, 6 (1): 7–12, doi:10.1109/TIT.1960.1057548.

- ↑ Du, Qiang; Emelianenko, Maria; Ju, Lili (2006), "Convergence of the Lloyd algorithm for computing centroidal Voronoi tessellations", SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 44: 102–119, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.591.9903, doi:10.1137/040617364.

- ↑ Sabin, M. J.; Gray, R. M. (1986), "Global convergence and empirical consistency of the generalized Lloyd algorithm", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 32 (2): 148–155, doi:10.1109/TIT.1986.1057168.

- ↑ Emelianenko, Maria; Ju, Lili; Rand, Alexander (2009), "Nondegeneracy and Weak Global Convergence of the Lloyd Algorithm in Rd", SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 46: 1423–1441, doi:10.1137/070691334.

- ↑ Xiao, Xiao. "Over-relaxation Lloyd method for computing centroidal Voronoi tessellations." (2010).

- ↑ Deussen, Oliver; Hiller, Stefan; van Overveld, Cornelius; Strothotte, Thomas (2000), "Floating points: a method for computing stipple drawings", Computer Graphics Forum, 19 (3): 41–50, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.233.5810, doi:10.1111/1467-8659.00396, S2CID 142991, Proceedings of Eurographics.

- ↑ Secord, Adrian (2002), "Weighted Voronoi stippling", Proceedings of the Symposium on Non-Photorealistic Animation and Rendering (NPAR), ACM SIGGRAPH, pp. 37–43, doi:10.1145/508530.508537, S2CID 12153589.

- ↑ Du, Qiang; Gunzburger, Max (2002), "Grid generation and optimization based on centroidal Voronoi tessellations", Applied Mathematics and Computation, 133 (2–3): 591–607, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.5020, doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(01)00260-0.

- ↑ Hausner, Alejo (2001), "Simulating decorative mosaics", Proceedings of the 28th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, ACM SIGGRAPH, pp. 573–580, doi:10.1145/383259.383327, S2CID 7188986.

- ↑ Dickerson, Matthew T.; Eppstein, David; Wortman, Kevin A. (2010), "Planar Voronoi diagrams for sums of convex functions, smoothed distance and dilation", Proc. 7th International Symposium on Voronoi Diagrams in Science and Engineering (ISVD 2010), pp. 13–22, arXiv:0812.0607, doi:10.1109/ISVD.2010.12, S2CID 15971504.

External links

- DemoGNG.js Graphical Javascript simulator for LBG algorithm and other models, includes display of Voronoi regions