| Martnaham Loch | |

|---|---|

Martnaham Loch at Jelliston | |

Martnaham Loch | |

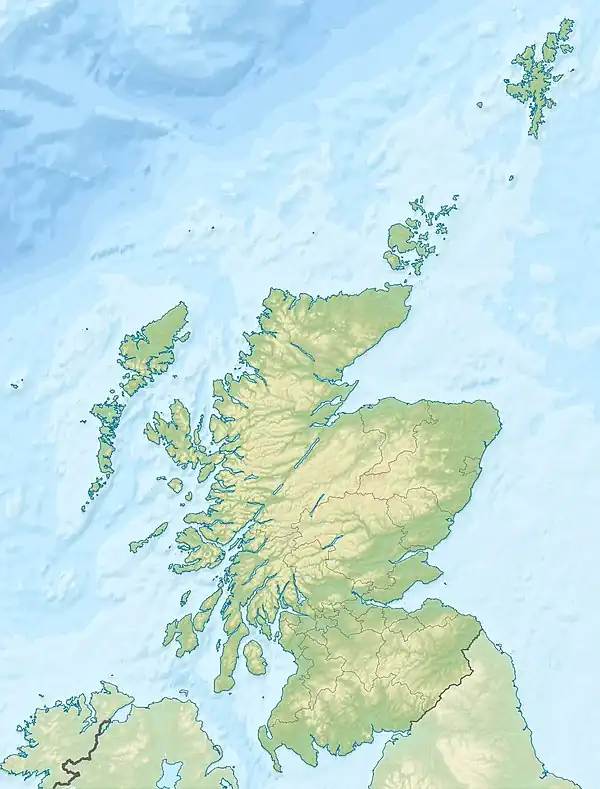

| Location | Coylton, South Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°25′24.2″N 4°32′23.4″W / 55.423389°N 4.539833°W |

| Lake type | Freshwater loch |

| Primary inflows | Snipe Loch Burn, Sandhill Burn, rainwater and field drainage |

| Basin countries | Scotland |

| Max. length | 1+1⁄4 mi (2 km) |

| Max. width | 1⁄4 mi (400 m) at maximum |

| Surface area | 113 acres (46 ha) |

| Max. depth | 29 ft (8.8 m) |

| Water volume | 47×106 cu ft (1.3×106 m3) |

| Surface elevation | 269 ft (82 m) |

| Islands | Two |

| Settlements | Ayr |

Martnaham Loch (NS 396 172) is a freshwater loch lying across the border between East and South Ayrshire Council Areas, two kilometres (1+1⁄4 miles) from Coylton, in the parishes of Coylton and Dalrymple, three miles (five kilometres) from Ayr. The loch lies along an axis from northeast to southwest. The remains of a castle lie on a possibly artificial islet[1] within the loch. The Campbells of Loudoun once held the lands, followed by the Kennedys of Cassillis.[2]

History

The loch

Martnaham Loch is a large post-glacial "Kettle Hole" fed by the Sandhill Burn, the Whitehill Burn and an outflow from Snipe Loch which in turn receives water from Loch Fergus.[3] The loch's outflow is at the south-west end and the Sandhill Burn enters at the north-east end. As stated the outflow from Loch Fergus passes into Snipe Loch, this flow entering between Cloncaird Cottages and Martnaham Lodge. A small islet lies off the eastern lochshore and a promontory, once an island, holds the ruins of the old castle.

- Etymology

Martnaham is variously recorded as Martinham, Martnam, Martna,[4] Matuane, and even Mertineton in 1700. The name may be Anglian or Gaelic and any connection with Saint Ninian's tutor, Saint Martin of Tours would be speculation.[5]

Martnaham Castle

The ruins of an old castle built on an island, recorded as Martnam Ynch (sic),[6] near the centre of the loch are still apparent (NS 3952 1732), the entrance having been from the south side of the loch, formed by a stone embankment or causeway from the land to the island. It is not clear when it was erected. It was inhabited till the 16th century. The remains are of a large building, 21 m × 7.5 m (69 ft × 25 ft), and the foundations of an annexe, 12 m × 5 m (39 ft × 16 ft), were visible to the northeast. The main block is divided into three compartments, and the walls are of mortared rubble masonry, 0.8 m (2 ft 7 in) thick, and attain a maximum height of 2.0 m (6 ft 7 in). Architectural features suggest a 16th/17th-century date. A possible rectangular building at the approach to the causeway may indicate the previous presence of a gatehouse.[7] The site has been densely wooded for many years.

Martnaham may have been part of a chain of fortalices forming a defensive line, including Drongan and Auchencloigh castles.[5] Love has it as the original seat of Old King Cole, thereby linking it with nearby Loch Fergus, named after King Cole's opponent and vanquisher.[3] Circa 1661 John Bonar, a schoolmaster in Ayr, wrote a poetical description of the local traditions regarding King Cole and states that[8] -

|

"The britones marchet, tuo dayes before the feild, |

The castle was the caput of the old Barony of Martnaham.[9] The site is said to have been besieged in the 1650s.[10] Groome[11] refers to it as "ivy-clad ruins of an old mansion house."

In 1612 John Monipennie noted the Loch of Matuane, with a strong tower.[12]

Paterson, writing in the 1860s,[1] gives some interesting details - "Only portions of three gables exist. The walls are not very thick, safety having apparently been chiefly relied upon because of its isolated situation. An artificial causeway, which could have been cut off at pleasure, leads to the ruin, and the island itself is evidently of the same character - being made of forced earth. It is thickly planted with trees, amongst which a colony of crows have continued to brood for ages. The garden is said to have been made of soil brought from France or Ireland, so as to exclude vermin. The Marquis of Ailsa has a shooting and fishing lodge on the banks of the loch, which is well stocked with pike and perch, the latter having been introduced within the last thirty years."

- Crannog

The Martnaham Castle island and causeway bear the characteristics of an adapted shallow water crannog and associated causeway as found in other Ayrshire lochs such as Lochspouts, Buiston, Lochlea, Loch Brand, and Kilbirnie.

Bathymetrical Survey of the Fresh-Water Lochs of Scotland, 1897-1909

This survey carried out by James Murray in 1906 shows a maximum depth of 29 ft (8.8 m) in the eastern section, with a depth of around 5 ft (1.5 m) near the old castle and along much of the length of the loch margin. Areas of marshy ground and several inlets are present.[13]

Natural history

Martnaham Loch is a SSSI for the western half of its area. The south-western end of the loch is bordered by mixed woodland. Martnaham has had some notable rarities recorded over the years, such as smew, ring-necked duck, black tern, lesser scaup and hobby. Autumn and winter feature visits from flocks of goldeneye, wigeon, pochard and teal. Shoveler, scaup, long-tailed duck and gadwall are commonly seen and glaucous, Iceland and Mediterranean gulls are occasional visitors. Canada geese and whooper swans gather in the surrounding fields. Great crested and little grebe breed here. oystercatcher, curlew, redshank, common sandpiper, whimbrel, ruff, green sandpiper, black-tailed godwit, northern wheatear and whinchat are regular visitors.[14]

The loch is botanically-rich loch and Martnaham Wood is one of the largest oak woods in Ayrshire; although it was clear felled in 1914, it has regenerated with little disturbance. The loch exhibits vegetation of submerged, floating and emergent type plant communities. The margin has extensive areas of reed-swamp dominated by common reed. Branched bur-reed, water-plantain, nodding bur-marigold, trifid bur-marigold, greater spearwort, and eight-stamened waterwort are found at the site. In the deeper water white and yellow water-lilies dominate. Canadian pondweed is an invasive plant and is here in abundance. The loch is classed as mesotrophic (moderately nutrient-rich), however it has eutrophic characteristics.[15]

Martinham Wood is well established on the eastern side of the loch, featuring since at least the early 16th century with a fence or pale indicated.[6] As an ancient woodland site Martnaham Wood has a canopy dominated by oak and birch, with abundant hazel in the understorey; sanicle, bluebell and dog’s mercury are common. The woodland exhibits a wide diversity of fungi, mosses and liverworts, including the only Scottish record of the mushroom Mycena picta, once thought to be extinct in Great Britain.[15]

Uses

- Purclewan Mill

The outflow at the south-west end was in 1906 built up with stones to divert water into a lade supplying Purclewan Mill. No sluice was present and water flowed down both outflows.[16] William McCandlish and his younger brother Dr James McCandlish were both were born at Purclewan, sons of the hamlets blacksmith. James was a classmate of Robert Burns and they were good friends. His father, Henry, lent Burns a copy of The Life of Wallace which aroused his patriotism.[17]

Robert Burns is said to have written his first poem "Handsome Nell" at the mill based on either Nelly Blair or Nelly Kilpatrick (1759–1820) the daughter of the Miller, Alan Kilpatrick, who he may have first met here. The mill has long been abandoned and was last recorded as active in 1911.[17] The mill was developed as private housing with several additions.

- Martnaham Lodge

Martnaham Lodge was originally built as a fishing lodge by the Kennedys, Earls of Cassillis in the 19th century, incorporating an existing cottage. James Edward Shaw, the Ayrshire County Clerk and treasurer, lived at the lodge from 1900 to 1912. Shaw was the author of a book on the social history of Ayrshire.[18] James Edward Hunter enlarged the house for its then tenant, Herbert J. Dunsmuir, in 1929. The Cassillis Estate has sold this now Arts & Crafts inspired manorial dwelling to Mr Dunsmuir in 1945 and it passed to his daughter and Colonel Sir Bryce Knox, his son-in-law.[12]

- Curling and boating

In the 19th century Martnaham Loch was used for curling[19] and ice skating. In 2011 the loch was once again safe for ice skating.[20] Two boat houses are recorded on the western side of the loch on the early OS maps.

Micro-history

A mineral railway ran close to much of the eastern side of the loch serving a colliery in Coylton.

Whitehill Tilery wood records the 19th century tileworks that once existed there.

See also

References

- Notes

- 1 2 Paterson, Page 215

- ↑ Paterson, Page 216

- 1 2 Love, Page 277

- ↑ Moll's Map Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- 1 2 Campbell, Page 222

- 1 2 Blaeu Map Retrieved: 2011-06-22

- ↑ RCAHMS Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- ↑ Cuthbertson, Page 124

- ↑ Smith, Page 165

- ↑ Salter, Page 53

- ↑ Groome, Page 1186

- 1 2 Davis, Page 323

- ↑ Bathymetric Survey Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- ↑ Ayrshire Birding Archived 2011-09-04 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- 1 2 SNH Retrieved : 2011-06-23

- ↑ Bathymetric Survey Text Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- 1 2 Dougall, Page 62

- ↑ Love, Page 196

- ↑ Curling Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- ↑ YouTube Retrieved : 2011-06-22

- Sources

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0.

- Cuthbertson, D. C. Autumn in Kyle and the Charm of Cunninghame. London : Herbert Jenkins.

- Davis, Michael C. (1991). The Castles & Mansions of Ayrshire. Ardrishaig : spendrift Press.

- Dougall, Charles S. (1911). The Burns Country. London: A & C Black.

- Groome, Francis H. (1903). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland. London : Caxton Publishing Company.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. I. - I - Kyle. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Salter, Mike (2006). The Castles of South-West Scotland. Malvern : Folly. ISBN 1-871731-70-4.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. London : Elliot Stock.

External links

- "Martnaham Loch and Wood SSSI". Sitelink. Retrieved 16 December 2019.