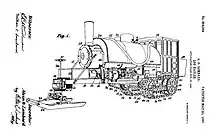

The Lombard Steam Log Hauler, patented 21 May 1901, was the first successful commercial application of a continuous track for vehicle propulsion.[1][2][3] The concept was later used for military tanks during World War I and for agricultural tractors and construction equipment following the war.

Description

Alvin Orlando Lombard was a blacksmith building logging equipment in Waterville, Maine. He built 83 steam log haulers between 1901 and 1917.[4] These log haulers resembled a saddle-tank steam locomotive with a small platform in front of the boiler where the cow-catcher might be expected.

A steering wheel on the platform moved a large pair of skis beneath the platform. A set of tracked vehicle treads occupied the space beneath the boiler where driving wheels might be expected. The locomotive cylinders powered the treads through a gear train. The log haulers mechanically resembled 10- to 30-ton snowmobiles with a top speed of about 4.5 miles per hour (7.2 km/h).[5]

Operation

While the ground was covered with snow and ice, a log hauler could tow a string of sleds filled with logs. Each sled train required a crew of four men. An engineer and fireman occupied the cab behind the boiler, and a steersman sat on the platform in front. A conductor rode on the sleds with a bell-rope or wire to signal the crew in the cab.[6] The earliest log haulers pulled three sleds, and later models were designed to pull eight sleds. Each train carried 40,000 to 100,000 board-feet of logs. The record train length was said to be 24 sleds with a total length of 1,650 feet (500 m).[4]

The greatest operational difficulty was on downhill grades where ice allowed the sleds to accelerate faster than the engine. Jack-knifing sleds pushed many log haulers into trees, and most photos of log haulers show rebuilt cabs and bent ironwork on the boiler and saddle tank. Hay was spread over the downhill routes in an effort to increase friction under the sleds, but hungry deer sometimes consumed the hay before the train arrived.

The steersman was regarded as the hero of the crew. In sub-freezing temperatures down to 40 degrees below zero, he sat in an exposed position in front of the train. Sparks flying out of the boiler stack above him would sometimes set his clothing on fire as avoidance of trees required his full attention and effort turning the large iron steering wheel. Some steersmen earned enough money to purchase fire-resistant leather clothing. Some log haulers had a small roofed shelter built on the steering platform, but the shelter limited the steersman's ability to jump clear when collision became inevitable, and he would require luck to avoid injury from the following trainload of logs.[7]

Berlin Mills Company was one of the larger woods operators to use Lombard log haulers. They purchased one machine in 1904, and then purchased two more to maintain reliable operation when one needed repairs. The company maintained a single 6-mile-long (10 km) iced haul road in Stetson, Maine, by nightly application of water from a sprinkler sled, and strung a telephone line with frequent call boxes to dispatch sled trains over that road. The company estimated those three Lombard log haulers did the work of 60 horses.[8]

History

The first two Lombard log haulers were used near Eustis, Maine, in 1901 prior to construction of the Eustis Railroad. These early machines had an upright boiler and were steered by a team of horses.[3] Most of the Lombard log haulers were used in Maine and New Hampshire. A few were used in Michigan, Wisconsin and Russia. Lombard began building 6-cylinder gasoline-powered log haulers in 1914, produced a more powerful "Big 6" later, and built one Fairbanks-Morse Diesel engine hauler in 1934. The internal combustion log haulers (called Lombard tractors) were less powerful than the steam log haulers; and resembled a stake body truck on a skis and tracks chassis. The steam-powered haulers are thought to have been used as late as 1929.[9] At least ten of the Lombard tractors were preserved at Churchill Depot as recently as the 1960s.[10]

Legacy

Antarctic Mount Lombard was named in recognition of the Lombard Log Hauler as the first application of knowledge of snow mechanics to trafficability.[11] The Lombard Steam Log Hauler was designated a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark in 1982 following nomination by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.[12]

Lombard Steam Log Haulers have been preserved and restored in:

- Ashland, Maine

- Maine Forest & Logging Museum in Bradley, Maine

- Owls Head Transportation Museum in Owls Head, Maine

- Lumberman's Museum in Patten, Maine

- Clark's Trading Post in Lincoln, New Hampshire

- Rhinelander, Wisconsin

- Saskatchewan Western Development Museum in Saskatoon

- Waterville, Maine

- Tulppio, Finland

- Rovaniemi Forestry Museum, Finland

Notes

- ↑ Alvin O. Lombard, Logging Engine, U.S. Patent 674,737, granted May 21, 1901.

- ↑ Alvin O. Lombard, Log Hauler, U.S. Patent 854,364, granted May 21, 1907.

- 1 2 Auman (1984) p.99

- 1 2 Auman (1984) p.100

- ↑ Holbrook (1961) pp.77-80

- ↑ Holbrook (1961) p.78

- ↑ Holbrook (1961) pp.78&79

- ↑ Holbrook (1961) pp.78-9

- ↑ Holbrook (1961) p.79

- ↑ Strout, W. Jerome (1966). 75 Years The Bangor and Aroostook. Bangor, Maine: Bangor and Aroostook Railroad. p. 45.

- ↑ "Mount Lombard". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ "The Lombard Log Hauler A National Historic Engineering Landmark" (PDF). State of Maine. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

References

- Holbrook, Stewart H. (1961). Yankee Loggers. International Paper Company.

- Auman, Jim (December 1984). "Lombard log hauler". Railroad Model Craftsman.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Walker, Martitia (March 1981). "470 Railroad Club Newsletter". Emmons Lancaster.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Springer, Elaine (May 1973). "Log Hauler in Wytopitlock". Maine Life.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)