| Lorin C. Woolley | |

|---|---|

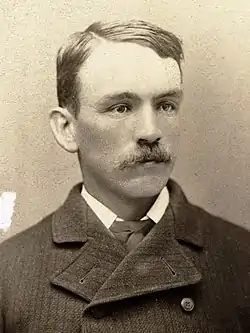

Woolley in 1882 | |

| Senior Member of the Priesthood Council | |

| December 13, 1928 – September 19, 1934 | |

| Predecessor | John W. Woolley |

| Successor | J. Leslie Broadbent (fundamentalists)[1] John Y. Barlow (FLDS Church)[2][3] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Lorin Calvin Woolley October 23, 1856 Great Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, U.S. |

| Died | September 19, 1934 (aged 77) Centerville, Utah, U.S. |

| Resting place | Centerville City Cemetery 40°54′47″N 111°52′05″W / 40.913°N 111.868°W |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Ann Roberts, Goulda Kmetzsch, possibly others |

| Children | 9 |

| Parents | John W. Woolley Julia Searles Ensign |

| Signature | |

| |

Lorin Calvin Woolley (October 23, 1856 – September 19, 1934) was an American proponent of plural marriage and one of the founders of the Mormon fundamentalist movement. As a young man in Utah Territory, Woolley served as a courier and bodyguard for polygamous leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in hiding during the federal crusade against polygamy. His career as a religious leader in his own right commenced in the early twentieth century, when he began claiming to have been set apart to keep plural marriage alive by church president John Taylor in connection with the 1886 Revelation.[4][5] Woolley's distinctive teachings on authority, morality, and doctrine are thought to provide the theological foundation for nearly ninety percent of Mormon fundamentalist groups.[6]

Early life

Woolley was the third child of Mormon pioneer John W. Woolley and his first wife, Julia Searles Ensign. His paternal grandfather was Bishop Edwin D. Woolley, a close friend of Brigham Young.[7] According to LDS Church records, Woolley was baptized a member of the church by his father on October 18, 1868, aged eleven, and ordained an elder by John Lyon on March 10, 1873.[8] Nicknamed "Noisy," the boisterous young Woolley frequently dominated Elders Quorum discussions.[9] Late in life, he would claim to have received his endowment and been ordained an deacon by Young on March 20, 1870, aged thirteen.[10]

On January 5, 1883, Woolley married Sarah Ann Roberts in the Endowment House on Temple Square. They had nine children together between 1883 and 1905: seven sons and two daughters.[11]

Woolley served as a Mormon missionary in the Southern United States from October 1887, to October 1889.[12] Shortly thereafter, he was called to the Seventieth Quorum of the Seventy in Centerville, Utah, and served a second, four-month mission to Indian Territory from December 1896 to April 1897.[13] In 1922, Woolley related a spiritual experience that had allegedly taken place during his first mission, wherein he fell deathly ill and only recovered after the resurrected Jesus Christ, Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and John Taylor intervened on his behalf.[14][15]

Plural marriage

Between October 1886 and February 1887, Woolley served as a mail carrier for LDS Church leaders hiding from state authorities during the crackdown on Mormon polygamy.[16] During this time, church authorities frequently stayed at the Woolley home in Centerville, Utah.[17]

On October 6, 1912, Woolley wrote the first known account of the reception of the 1886 Revelation, an enigmatic document in the handwriting of church president John Taylor. This revelation declared firmly that the Lord had not revoked the "New and Everlasting Covenant", "nor will I, for it is everlasting."[18] According to Woolley, Taylor had written the document after being visited by the resurrected Joseph Smith, founder of the church, at Woolley's father's home in September 1886.[19] Woolley frequently reiterated this account over the remainder of his life, adding additional details over time. The version which has assumed canonical status among Mormon fundamentalists was compiled by Joseph W. Musser in 1929, and includes the claim that Smith's appearance was followed by an "eight hour meeting" on September 27, 1886, at which President Taylor put five men (Woolley and his father, George Q. Cannon, Samuel Bateman, and Charles Henry Wilcken) under covenant to ensure that "no year passed by without children being born in the principle of plural marriage."[20] According to Woolley, these five men, together with Taylor himself and later Joseph F. Smith, comprised a seven-man "Council of Friends" holding apostolic authority above that of the LDS Church. This doctrinal claim gave hierarchical structure to the nascent fundamentalist movement, previously an informal association of LDS Church dissidents. Woolley's father, the aged John W. Woolley, a Salt Lake Temple sealer, was considered spiritual head of the organization. The elder Woolley was excommunicated from the LDS Church for performing plural marriages in April 1914.[21]

Woolley was excommunicated from the LDS Church in January 1924 for alleging that church president Heber J. Grant and apostle James E. Talmage had taken plural wives "in the recent past." Woolley claimed that he had learned of such behavior because he was employed by the United States Secret Service to spy on LDS Church leaders. The official reason for his excommunication was that he was "found guilty of pernicious falsehood."[16][22] Grant publicly denied Woolley's claims in a general conference of the church in April 1931.[23]

Mormon fundamentalist leader

Most Mormon fundamentalists believe that, upon his father's death in December 1928, Woolley succeeded him as senior member of the Council of Friends, and thus "President of the Priesthood" or prophet. Between March 1929 and January 1933, Woolley ordained six new members to the council, designating them apostles and patriarchs: J. Leslie Broadbent, John Y. Barlow, Joseph White Musser, Charles Zitting, LeGrand Woolley, and Louis A. Kelsch. In November 1933, Broadbent was appointed Woolley's "Second Elder" and successor designate, "holding the keys to revelation jointly with himself."[24] Despite Woolley's appointment, some contemporary fundamentalist groups, such as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church), believe that he was succeeded as prophet by Barlow.[3]

Although historian Brian C. Hales writes that "by all known accounts, Lorin C. Woolley was a monogamist until he was seventy-five years old," when he married twenty-eight-year-old Goulda Kmetzsch, Woolley himself claimed to have "five wives living" in April 1933.[25][26] Some of his followers have attempted to resolve this discrepancy by speculating that Woolley was married to at least three of his own first cousins, possibly including Alice, Viola, Lucy, or Elnora Woolley, whom fundamentalist author Lynn L. Bishop argues had married Lorin by at least 1915. Others believe that Woolley anonymously wed a plural wife in the Yucatán Peninsula, where he claimed to have been divinely transported on several occasions.[27] Historians Marianne T. Watson and Craig L. Foster suggest Woolley may have married Edith Gamble, a Salt Lake City widow, as a plural wife around September 1923.[28]

According to Hales, Woolley made numerous extraordinary claims about himself throughout his later life, such as alleging that he had once been employed by the United States Secret Service to spy on LDS Church leaders. Woolley used the latter claim as a basis for accusing then-President Heber J. Grant and several other high-ranking church officials of having secretly entered into plural marriages. This rumor proved scandalous enough that Grant publicly repudiated it in 1931. Woolley also claimed that US Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge were not only clandestine allies of the Mormon fundamentalists but that they were baptized Mormons; he went as far as to allege that he'd personally converted Roosevelt and that the former President practiced polygamy. Woolley made similar claims about Presidents William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson and Herbert Hoover, but said they "have broken their covenants".[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hales, Brian C. "J. Leslie Broadbent". mormonfundamentalism.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Official website of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints: President Lorin C. Woolley". Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 Jeffs (1997, p. 243).

- ↑ Altman & Ginat (1996, pp. 43–44).

- ↑ Driggs (1990, p. 40).

- ↑ Hales (2006, p. 433).

- ↑ Parkinson (1967, p. 313).

- ↑ LDS Church Membership Records, South Davis Stake, cited in Anderson (1979, p. 145).

- ↑ Centerville Fifth Ward Elders Quorum minutes, cited in Anderson (1979).

- ↑ Musser (n.d., p. 10)

- ↑ Parkinson (1967, pp. 313–14).

- ↑ Missionary Book B, p. 97, no. 236, LDS Church History Department, cited in Anderson (1979, p. 145).

- ↑ Missionary Book C, p. 38, no. 741, LDS Church History Department, cited in Anderson (1979, p. 145).

- ↑ Journal of Joseph W. Musser, April 9, 1922.

- ↑ Musser (n.d., pp. 10–11)

- 1 2 3 Brian C. Hales, "'I Love to Hear Him Talk and Rehearse': The Life and Teachings of Lorin C. Woolley", Mormon History Association, 2003.

- ↑ Driggs (1990, p. 40) ("The Woolley home was a favorite stop for [John] Taylor. He often met there with other Church leaders to conduct Church business.")

- ↑ Hales (2006, p. 37).

- ↑ Hales (2006, p. 146).

- ↑ Hales (2006, pp. 151–52, 479–82).

- ↑ Driggs (2005, pp. 67–68).

- ↑ James E. Talmage Correspondence File, January 18, 1924, LDS Church History Department, cited in Anderson (1979, p. 146).

- ↑ One-Hundred and First Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: 1931), 10.

- ↑ Drew Briney (ed.), Lorin C. Woolley's School of the Prophets Minutes from 1932–1941 (Mona, Utah: Hindsight Publications, 2009), 3.

- ↑ Hales (2006, p. 307)

- ↑ Musser (n.d., pp. 33–35).

- ↑ Lynn L. Bishop,The 1886 Visitations of Jesus Christ and Joseph Smith to John Taylor: The Centerville Meetings (Salt Lake City: Latter Day Publications, 1998), 194-95, 202, cited in Hales (2006, p. 157).

- ↑ Newell Bringhurst and Craig L. Foster (eds.), The Persistence of Polygamy, Volume 3: Fundamentalist Mormon Polygamy from 1890 to the Present (Independence: John Whitmer Books, 2015), 154-55, 479.

References

- Altman, Irwin; Ginat, Joseph (1996), Polygamous Families in Contemporary Society, Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, J. Max (1979), The Polygamy Story: Fiction and Fact, Publishers Press.

- Driggs, Ken (1990). "Fundamentalist Attitudes toward the Church: The Sermons of Leroy S. Johnson". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 23: 39–60. doi:10.2307/45228077. JSTOR 45228077. S2CID 254393431..

- Driggs, Ken (2005). "Imprisonment, Defiance, and Division: A History of Mormon Fundamentalism in the 1940s and 1950s". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 38 (1): 65–95. doi:10.2307/45228177. JSTOR 45228177. S2CID 254391753..

- Hales, Brian C. (2006), Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto, Sandy, Utah: Greg Kofford Books.

- Jeffs, Rulon T. (1997), History of Priesthood Succession in the Dispensation of the Fullness of Times and Some Challenges to the One Man Rule, Hildale, Utah: Twin City Courier Press.

- Musser, Joseph W. (n.d.), Items from a Book of Remembrance of Joseph W. Musser, privately published.

- Parkinson, Preston W. (1967), The Utah Woolley Family, Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News Press.

External links

- President Lorin C. Woolley at the Wayback Machine (archived August 3, 2010) - Biography of Lorin C. Woolley located at fldstruth.org (former official FLDS website)

- The Life and Teachings of Lorin C. Woolley