| Snake River Lewis River, Shoshone River, Mad River, Saptin River, Yam-pah-pa, Lewis Fork | |

|---|---|

The Tetons - Snake River, a 1942 photograph by Ansel Adams | |

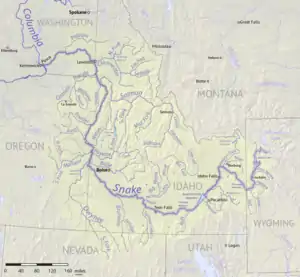

Map of the Snake River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington |

| Region | Pacific Northwest |

| Cities | Jackson, WY, Idaho Falls, ID, Blackfoot, ID, American Falls, ID, Burley, ID, Twin Falls, ID, Ontario, OR, Lewiston, ID, Clarkston, WA, Tri-Cities, WA |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Rocky Mountains |

| • location | Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming |

| • coordinates | 44°08′24″N 110°13′08″W / 44.1399°N 110.2189°W[1] |

| • elevation | 9,206 ft (2,806 m)[1] |

| Mouth | Columbia River at Lake Wallula |

• location | Franklin / Walla Walla counties, near Burbank, Washington[2] |

• coordinates | 46°11′10″N 119°1′43″W / 46.18611°N 119.02861°W[3] |

• elevation | 358 ft (109 m)[4] |

| Length | 1,078 mi (1,735 km)[5] |

| Basin size | 108,000 sq mi (280,000 km2)[6] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Ice Harbor Dam, Washington, 9+1⁄2 miles (15.3 km) above the mouth[7] |

| • average | 54,830 cu ft/s (1,553 m3/s)[7] |

| • minimum | 2,700 cu ft/s (76 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 409,000 cu ft/s (11,600 m3/s)[8] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Hoback River, Salt River, Portneuf River, Bruneau River, Owyhee River, Malheur River, Burnt River, Powder River, Imnaha River, Grande Ronde River |

| • right | Henrys Fork, Malad River, Boise River, Payette River, Weiser River, Salmon River, Clearwater River, Palouse River |

| Type | Wild 260.8 miles (419.7 km) Scenic 186.4 miles (300.0 km) Recreational 33.8 miles (54.4 km) |

| Reference no. | P.L. 94-199; P.L. 111-11[9] |

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At 1,078 miles (1,735 km) long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean.[10] The Snake River rises in western Wyoming, then flows through the Snake River Plain of southern Idaho, the rugged Hells Canyon on the Oregon–Idaho border and the rolling Palouse Hills of Washington, emptying into the Columbia River at the Tri-Cities in the Columbia Basin of Eastern Washington.

The Snake River drainage basin encompasses parts of six U.S. states (Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Utah, Nevada, and Wyoming) and is known for its varied geologic history. The Snake River Plain was created by a volcanic hotspot which now lies underneath the Snake River headwaters in Yellowstone National Park. Gigantic glacial-retreat flooding episodes during the previous Ice Age carved out canyons, cliffs, and waterfalls along the middle and lower Snake River. Two of these catastrophic flooding events, the Missoula Floods and Bonneville Flood, significantly affected the river and its surroundings.

Native Americans have lived along the Snake for more than 11,000 years. Salmon from the Pacific Ocean spawned by the millions in the river and were a vital resource for people living on the Snake downstream of Shoshone Falls. By the time Lewis and Clark explored the area, the Nez Perce and Shoshone were the dominant Native American groups in the region. Later explorers and fur trappers further changed and used the resources of the Snake River basin. At one point, the sign language used by the Shoshones representing weaving baskets was misinterpreted to represent a snake, giving the Snake River its name.[11]

By the middle 19th century, the Oregon Trail had become well established, bringing numerous settlers to the Snake River region. Steamboats and railroads moved agricultural products and minerals along the river throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Starting in the 1890s, fifteen major dams were built on the Snake River to generate hydroelectricity, enhance navigation, and provide irrigation water. However, these dams blocked salmon migration above Hells Canyon and have led to water quality and environmental issues in certain parts of the river. The removal of several dams on the lower Snake River has been proposed in order to restore some of the river's once-tremendous salmon runs.

Course

Formed by the confluence of three tiny streams on the southwest flank of Two Oceans Plateau in Yellowstone National Park, western Wyoming, the Snake starts out flowing west and south into Jackson Lake. Its first 50 miles (80 km) run through Jackson Hole, a wide valley between the Teton Range and the Gros Ventre Range. Below the tourist town of Jackson, the river turns west and flows through Snake River Canyon, cutting through the Snake River Range and into eastern Idaho. It receives the Hoback and Greys Rivers before entering Palisades Reservoir, where the Salt River joins at the mouth of Star Valley. Below Palisades Dam, the Snake River flows through the Snake River Plain, a vast arid physiographic province extending through southern Idaho southwest of the Rocky Mountains and underlain by the Snake River Aquifer, one of the most productive aquifers in the United States.[12][13][14][15][16]

Southwest of Rexburg, Idaho, the Snake is joined from the north by Henrys Fork. The Henrys Fork is sometimes called the North Fork of the Snake River, with the main Snake above their confluence known as the "South Fork". From there, it turns south, flowing through downtown Idaho Falls, then past the Fort Hall Indian Reservation and into American Falls Reservoir, where it is joined by the Portneuf River. The Portneuf River Valley is an overflow channel that in the last glacial period carried floodwaters from pluvial Lake Bonneville into the Snake River, significantly altering the landscape of the Snake River Plain through massive erosion. From there, the Snake resumes its journey west, entering the Snake River Canyon of Idaho. It is interrupted by several major cataracts, the largest being 212-foot (65 m) Shoshone Falls, which historically marked the upriver limit of migrating salmon.[12][17] A short distance downstream it passes under the Perrine Bridge.[13][18] Near Twin Falls, the Snake approaches the southernmost point in its entire course, after which it starts to flow west-northwest.[12][13][15][16]

The Snake continues through its canyon, receiving the Malad River from the east near Bliss and then the Bruneau River from the south in C.J. Strike Reservoir. It passes through an agricultural valley about 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Boise and flows briefly west into Oregon, before turning north to define the Idaho–Oregon border. Here the Snake River almost doubles in size as it receives several major tributaries – the Owyhee from the southwest, then the Boise and Payette rivers from the east, and farther downstream the Malheur River from the west and Weiser River from the east. North of Boise, the Snake enters Hells Canyon, a steep, spectacular, rapid-strewn gorge that cuts through the Salmon River Mountains and Blue Mountains of Idaho and Oregon. Hells Canyon is one of the most rugged and treacherous portions of the course of the Snake River, posing a major obstacle for 19th-century American explorers. Here the Snake is also impounded by Hells Canyon, Oxbow, and Brownlee Dams, which together make up the Hells Canyon Hydroelectric Project.[12][15][16][19]

At the halfway point in Hells Canyon, in one of the most remote and inaccessible sections of its course, the Snake River is joined from the east by its largest tributary, the Salmon River. From there, the Snake begins to form the Washington–Idaho border, receiving the Grande Ronde River from the west before receiving the Clearwater River from the east at Lewiston, which marks the head of navigation on the Snake. The river leaves Hells Canyon and turns west, winding through the Palouse Hills of eastern Washington. The Lower Snake River Project's four dams and navigation locks have transformed this part of the Snake River into a series of reservoirs. The confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers at Burbank, Washington is part of Lake Wallula, the reservoir of McNary Dam. The Columbia River flows about 325 miles (523 km) farther west to the Pacific Ocean near Astoria, Oregon.[12][15][16]

Geology

.jpg.webp)

Most of western North America was drowned by shallow seas off and on from around 800–200 million years ago. This was the accumulation phase of the mountain building cycle, where mostly sedimentary rocks accumulate as the seafloor subsides. The western edge of North America was a passive continental margin and therefore was not near a plate boundary. 180 million years ago, the tectonic setting of western North America changed to an active continental margin, and a convergent plate boundary formed, which crumpled the deposits from the accumulation phase into fold-thrust mountain ranges. Plate convergence gave rise to the Coastal Ranges and then to the Rocky Mountains due to friction between the Farallon Plate sinking beneath the North American Plate. Another tectonic player is the Yellowstone hotspot, which is a large plume of partially molten material lodged in the mantle. As the North American Plate moved west–southwest over the hot spot, massive amounts of basaltic lava were extruded onto the crust. The load of these dense lava flows bent down the crust immediately below it, and the mountains formed earlier to make the WSW-ENE oriented trough known as the Snake River Plain. The river did not carve the Snake River Plain, but rather the Snake River took the course of least resistance and followed the path formed by the hot spot through the Rocky Mountains. The first lava flows started pouring out in what is now the western part of the Snake River Plain and is still extruding in the eastern part of the plain.[20] Even larger lava flows of Columbia River basalts issued over eastern Washington, forming the Columbia Plateau southeast of the Columbia River and the Palouse Hills in the lower Snake.[21] Separate volcanic activity formed the northwestern portion of the plain, an area far from the path of the hotspot The hot spot now resides beneath Yellowstone National Park. The heat from the molten rock beneath the park domes the crust up to form the Yellowstone Plateau.[20]

The Snake River Plain and the gap between the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range together formed a "moisture channel," opening the way for Pacific storms to travel more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) inland to the headwaters of the Snake River. When the Teton Range uplifted about 9 million years ago along a detachment fault running north–south through the central Rockies,[22] the river maintained its original course and cut through the southern end of the mountains, forming the Snake River Canyon of Wyoming. About 6 million years ago, the Salmon River Mountains and Blue Mountains at the far end of the plain began to rise; the river cut through these mountains as well, forming Hells Canyon. Lake Idaho, formed during the Miocene, covered a large portion of the Snake River Plain between Twin Falls and Hells Canyon, and its lava dam was finally breached about 2 million years ago.[23]

Lava flowing from Cedar Butte in present southeast Idaho blocked the Snake River at Eagle Rock about 42,000 years ago, near the present-day site of American Falls Dam. A 40-mile-long (64 km) lake, known as American Falls Lake, formed behind the barrier. The lake was stable and survived for nearly 30,000 years. About 14,500 years ago, pluvial Lake Bonneville in the Great Salt Lake area, formed in the last glacial period, spilled catastrophically down the Portneuf River into the Snake in an event known as the Bonneville flood.[24] This was one of the first in a series of catastrophic flooding events in the Northwest known as the Ice Age Floods.

The deluge caused American Falls Lake to breach its natural lava dam, which was rapidly eroded with only the 50-foot-high (15 m) American Falls left in the end. The flood waters of Lake Bonneville, approximately twenty times the flow of the Columbia River or 5 million ft3/s (140,000 m3/s), swept down the Snake River and across the entirety of southern Idaho. For miles on either side of the river, flood waters stripped away soils and scoured the underlying basalt bedrock, transforming the region into channeled scablands[25] forming the Snake River Canyon and creating Shoshone Falls, Twin Falls, Crane Falls, Swan Falls and other waterfalls along the Idaho section of the river.[26] The Bonneville flood waters continued through Hells Canyon and eventually reached the Columbia River. The flood widened Hells Canyon but did not deepen it.[27][28]

As the Bonneville Floods rushed down the Snake River, the Missoula Floods occurred in the same period, but originating farther north. The Missoula Floods, which occurred more than 40 times between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago, were caused by Glacial Lake Missoula on the Clark Fork repeatedly being impounded by ice dams then breaking through, with the lake's water rushing over much of eastern Washington in massive surges far larger than the Lake Bonneville Flood. These floods pooled behind the Cascade Range into enormous lakes and spilled over the northern drainage divide of the Snake River watershed, carving deep canyons through the Palouse Hills including the Palouse River canyon and Palouse Falls. The Lake Bonneville Floods and the Missoula Floods helped widen and deepen the Columbia River Gorge, a giant water gap which allows water from the Columbia and Snake rivers to take a direct route through the Cascade Range to the Pacific.[27][29][30]

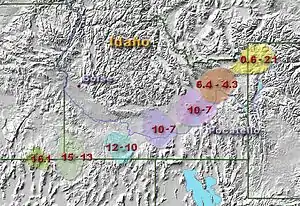

The massive amounts of sediment deposited by the Lake Bonneville Floods in the Snake River Plain also had a lasting effect on most of the middle Snake River. The high hydraulic conductivity of the mostly-basalt rocks in the plain led to the formation of the Snake River Aquifer, one of the most productive aquifers in North America. Many rivers and streams flowing from the north side of the plain sink into the aquifer instead of flowing into the Snake River, a group of watersheds called the lost streams of Idaho.[31] The aquifer filled to hold nearly 100,000,000 acre-feet (120 km3) of water, underlying about 10,000 square miles (26,000 km2) in a plume 1,300 feet (400 m) thick.[32] In places, water exits from rivers at rates of nearly 600 cubic feet per second (17 m3/s).[26] Much of the water lost by the Snake River as it transects the plain issues back into the river at its western end, by way of many artesian springs.[14][33][34]

Watershed

The Snake River is the thirteenth longest river in the United States.[10] Its watershed is the 10th largest among North American rivers, and covers almost 108,000 square miles (280,000 km2) in portions of six U.S. states: Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Oregon, and Washington, with the largest portion in Idaho. Most of the Snake River watershed lies between the Rocky Mountains on the east and the Columbia Plateau on the northwest. The largest tributary of the Columbia River, the Snake River watershed makes up about 41% of the entire Columbia River Basin. Its average discharge at the mouth constitutes 31% of the Columbia's flow at that point.[35][36] Above the confluence, the Snake is slightly longer than the Columbia—1,078 miles (1,735 km)[5] compared to 928 miles (1,493 km)[37]—and its drainage basin is slightly larger—4% bigger than the upstream Columbia River watershed.[6][38]

The mostly semi-arid, even desert climate of the Snake River watershed on average, receives less than 12 inches (300 mm) of precipitation per year. However, precipitation in the Snake River watershed varies widely. At Twin Falls, in the center of the Snake River Plain, the climate is nearly desert, with an annual rainfall of just 9.24 inches (235 mm), although the average snowfall is 13.1 inches (330 mm).[39] This desert climate occupies the majority of the basin of the Snake River, so although it is longer than the Columbia River above the Tri-Cities, its average discharge is significantly less. However, in the high Rockies of Wyoming, in the upper Jackson Hole area, the average precipitation is over 30 inches (760 mm), and snowfall averages 252 inches (6,400 mm).[40] Most of the Snake River basin consists of wide, arid plains and rolling hills, bordered by high mountains. In the upper parts of the watershed, however, the river flows through an area with a distinct alpine climate. There are also stretches where the river and its tributaries have incised themselves into tight gorges. The Snake River watershed includes parts of Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, and many other national and state parks.

Much of the area along the river, within a few miles of its banks, is irrigated farmland, especially in its middle and lower course. Irrigation dams include American Falls Dam, Minidoka Dam, and C.J. Strike Dam. Aside from water from the river, water is also pulled from the Snake River Aquifer for irrigation. Major cities along the river include Jackson in Wyoming, Twin Falls, Idaho Falls, Boise, and Lewiston in Idaho, and the Tri-Cities in Washington (Kennewick, Pasco and Richland). There are fifteen dams in total along the Snake River, which aside from irrigation, also produce electricity, maintain a navigation channel along part of the river's route, and provide flood control.[41] However, fish passage is limited to the stretch below Hells Canyon.[42]

The Snake River watershed is bounded by several other major North American watersheds, which drain both to the Atlantic or the Pacific, or into endorheic basins. On the southwest side, a divide separates the Snake watershed from Oregon's Harney Basin, which is endorheic. On the south, the Snake watershed borders that of the Humboldt River in Nevada, and the watershed of the Great Salt Lake (the Bear, Jordan and Weber rivers) on the south.[43] The Snake River also shares a boundary with the Green River to the southeast; the Green River drains parts of Wyoming and Utah and is the largest tributary of the Colorado River. On the western extremity, for a short stretch, the Continental Divide separates the Snake watershed from the Bighorn River, a tributary of the Yellowstone River, which the Snake begins near. On the north the Snake River watershed is bounded by the Red Rock River, a tributary of the Beaverhead River, which flows into the Jefferson River and into the Missouri River, part of the Gulf of Mexico drainage basin.[43]

The rest of the Snake River watershed borders on several other major Columbia River tributaries - mostly the Spokane River to the north, but also Clark Fork in Montana to the northeast and the John Day River to the west. Of these, the Clark Fork (via the Pend Oreille River) and the Spokane join the Columbia above the Snake, while the John Day joins downstream of the Snake, in the Columbia River Gorge. The northeastern divide of the Snake River watershed forms the Idaho-Montana boundary, so the Snake River watershed does not extend into Montana.[43]

Mountain ranges in the Snake watershed include the Teton Range, Bitterroot Range, Clearwater Mountains, Seven Devils Mountains, and the extreme northwestern end of the Wind River Range. Grand Teton is the highest point in the Snake River watershed, reaching 13,775 feet (4,199 m) in elevation. The elevation of the Snake River is 358 feet (109 m) when it joins the Columbia River.[3]

Pollution

Agricultural runoff from farms and ranches in the Snake River Plain and many other areas has severely damaged the ecology of the river throughout the 20th century. After the first irrigation dams on the river began operation in the first decade of the 20th century, much of the arable land in a strip a few miles wide along the Snake River was cultivated or turned to pasture, and agricultural return flows began to pollute the Snake. Runoff from several feedlots was dumped into the river until laws made the practice illegal.[44] Fertilizer, manure and other chemicals and pollutants washed into the river greatly increase the nutrient load, especially of phosphorus, fecal coliforms and nitrogen. During low water, algae blooms occur throughout the calm stretches of the river, depleting its oxygen supply.[45]

Much of the return flows do not issue directly back into the Snake River, but rather feed the Snake River Aquifer underneath the Snake River Plain. Water diverted from the river for irrigation, after absorbing any surface pollutants, re-enters the ground and feeds the aquifer. Although the aquifer has maintained its level, it has become increasingly laced with contaminants. Water in the aquifer eventually travels to the west side of the Snake River Plain and re-enters the river as springs.[46] Throughout much of the Snake River Plain and Hells Canyon, excessive sediment is also a recurring problem.[47] In December 2007, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a permit requiring owners of fish farms along the Snake River to reduce their phosphorus discharge by 40%. Pollutant levels in Hells Canyon upstream of the Salmon River confluence, including that of water temperature, dissolved nutrients, and sediment, are required to meet certain levels.[48]

Discharge

The Snake River's average flow is 54,830 cubic feet per second (1,553 m3/s). The United States Geological Survey recorded the river's discharge from a period of 1963–2000 at a stream gauge below Ice Harbor Dam. In that period, the largest average annual flow recorded was 84,190 cu ft/s (2,384 m3/s) in 1997, and the lowest was 27,100 cu ft/s (770 m3/s) in 1992.[7] The lowest recorded daily mean flow was 2,700 cu ft/s (76 m3/s) on February 4, 1979. On August 27, 1965, there was temporarily no flow as a result of testing at Ice Harbor Dam. The highest recorded flow was 312,000 cu ft/s (8,800 m3/s) on June 19, 1974.[7] The highest flow ever recorded on the Snake River was at a different USGS stream gauge near Clarkston, which operated from 1915 to 1972. This gauge recorded a maximum flow of 369,000 cu ft/s (10,400 m3/s)—more than the Columbia's average discharge—on May 29, 1948. An even larger peak discharge, estimated at 409,000 cu ft/s (11,600 m3/s), occurred during the flood of June 1894.[8]

The river's flow is also measured at several other points in its course. Above Jackson Lake, Wyoming, the discharge is about 885 cu ft/s (25.1 m3/s) from a drainage area of 486 square miles (1,260 km2).[49] At Minidoka, Idaho, about halfway through the Snake River Plain, the river's discharge rises to 7,841 cu ft/s (222.0 m3/s).[50] However, at Buhl, Idaho, only about 50 miles (80 km) downstream, the river's flow decreases to 4,908 cu ft/s (139.0 m3/s) because of agricultural diversions and seepage.[51] But at the border of Idaho and Oregon, near Weiser at the beginning of Hells Canyon, the Snake's flow rises to 17,780 cu ft/s (503 m3/s) after receiving several major tributaries such as the Payette, Owyhee and Malheur.[52] The discharge further increases to 19,530 cu ft/s (553 m3/s) at Hells Canyon Dam on the border of Idaho and Oregon.[53] At Anatone, Washington, downstream of the confluence with the Salmon, one of the Snake's largest tributaries, the mean discharge is 34,560 cu ft/s (979 m3/s).[54]

History

Name

The name Snake River comes from the so-called "Snake Indians" who lived along the river, actually Shoshone, Bannock, and Northern Paiute. The "Snake Indian" name for those groups came from Plains Indians—possibly in reference to the use of snake heads in war or because the Plains Indians referred to these groups with a snake-like hand gesture, possibly originally intended to indicate a salmon.[55]

Canadian explorer David Thompson first recorded the Native American name of the Snake River as Shawpatin when he arrived at its mouth by boat in 1800. When the Lewis and Clark Expedition crossed westwards into the Snake River watershed in 1805, they first gave it the name Lewis River, Lewis Fork or Lewis's Fork, as Meriwether Lewis was the first of their group to sight the river.[56]

The group also learned that the Native Americans called the river Ki-moo-e-nim or Yam-pah-pa (for an herb that grew prolifically along its banks).[57] Later American explorers, some of whom were originally part of the Lewis and Clark expedition, journeyed into the Snake River watershed and records show a variety of names have been associated with the river. The explorer Wilson Price Hunt of the Astor Expedition named the river as Mad River. Others gave the river names including Shoshone River (after the tribe) and Saptin River.[3]

Early inhabitants

People have been living along the Snake River for at least 11,000 years. Historian Daniel S. Meatte divides the prehistory of the western Snake River Basin into three main phases or "adaptive systems". The first he calls "Broad Spectrum Foraging", dating from 11,500 to 4,200 years before present. During this period people drew upon a wide variety of food resources. The second period, "Semisedentary Foraging", dates from 4,200–250 years before present and is distinctive for an increased reliance upon fish, especially salmon, as well as food preservation and storage. The third phase, from 250 to 100 years before present, he calls "Equestrian Foragers". It is characterized by large horse-mounted tribes that spent long amounts of time away from their local foraging range hunting bison.[58] In the eastern Snake River Plain there is some evidence of Clovis, Folsom, and Plano cultures dating back over 10,000 years ago.

Early fur traders and explorers noted regional trading centers, and archaeological evidence has shown some to be of considerable antiquity. One such trading center in the Weiser area existed as early as 4,500 years ago. The Fremont culture may have contributed to the historic Shoshones, but it is not well understood. Another poorly understood early cultural component is called the Midvale Complex. The introduction of the horse to the Snake River Plain around 1700 helped in establishing the Shoshone and Northern Paiute cultures.[59][60]

On the Snake River in southeastern Washington there are several ancient sites. One of the oldest and most well-known is called the Marmes Rockshelter, which was used from over 11,000 years ago to relatively recent times. The Marmes Rockshelter was flooded in 1968 by Lake Herbert G. West, the Lower Monumental Dam's reservoir.[61]

Eventually, two large Native American groups controlled most of the Snake River: the Nez Perce, whose territory stretched from the southeastern Columbia Plateau into northern Oregon and western Idaho, and the Shoshone, who occupied the Snake River Plain both above and below Shoshone Falls. Lifestyles along the Snake River varied widely. Below Shoshone Falls, the economy centered on salmon, who often came up the river in enormous numbers. Salmon were the mainstay of the Nez Perce and most of the other tribes below Shoshone Falls. Above the falls, life was significantly different. The Snake River Plain forms one of the only relatively easy paths across the main Rocky Mountains for many hundreds of miles, allowing Native Americans both east and west of the mountains to interact. As a result, the Shoshone centered on a trading economy.

According to legend, the Nez Perce tribe was first founded in the valley of the Clearwater River, one of the Snake River's lowermost major tributaries. At its height, there were at least 27 Nez Perce settlements along the Clearwater River and 11 more on the Snake between the mouth of the Clearwater and Imnaha Rivers. There were also villages on the Salmon River, Grande Ronde River, Tucannon River, and the lower Hells Canyon area. The Snake River's annual salmon run, which was estimated at that time to exceed four million in good years, supported the Nez Perce, who lived in permanent, well-defined villages, unlike the nomadic southeastern tribes along the Snake River. The Nez Perce also were involved in trade with the Flathead tribe to the north and other middle Columbia River tribes. However, they were enemies to the Shoshone and the other upstream Snake River tribes.[62]

The Shoshone (or Shoshoni) were characterized by nomadic groups that took their culture from the earlier Bitterroot culture and Great Basin tribes that migrated north via the Owyhee River. They were the most powerful tribe in the Rocky Mountains area, and were known to many Great Plains tribes as the "Snakes". In the 18th century, Shoshone territory extended beyond the Snake River Plain, extending over the Continental Divide into the upper Missouri River watershed and even further north into Canada.[63] A smallpox epidemic brought by European explorers and fur trappers was responsible for wiping out much of the Shoshone east of the Rocky Mountains, but the Shoshone continued to occupy the Snake River Plain. Eventually, the Shoshone culture merged with that of the Paiute and Bannock tribes, which came from the Great Basin and the Hells Canyon area, respectively. The Bannock brought with them the skill of buffalo hunting and horses they had acquired from Europeans, changing the Shoshone way of life significantly.[64]

Exploration and settling

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–06) was the first American group to cross the Rocky Mountains and sail down the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific Ocean.[65] Meriwether Lewis supposedly became the first American to sight the drainage basin of the Snake River after he crossed the mountains a few days ahead of his party on August 12, 1805, and sighted the Salmon River valley (a major Snake tributary) from Lemhi Pass, a few miles from the present-day site of Salmon, Idaho. The party later traveled north, descended the Lemhi River to the Salmon and attempted to descend it to the Snake, but found it impassable because of its violent rapids. The expedition named the Snake River the Lewis River, Lewis's River, or Lewis Fork, in his honor, and they traveled northwards to the Lochsa River, which they traveled via the Clearwater River into the lower Snake, and into the Columbia. They also referred to the Shoshone Indians as the "Snake Indians", which became the present-day name of the river.[66][67] The name "Lewis Fork", however, did not last.[65]

Later American explorers traveled throughout the Snake River area and up its major tributaries beginning in 1806, just after Lewis and Clark had returned. The first was John Ordway in 1806, who also explored the lower Salmon River. John Colter in 1808 was the first to sight the upper headwaters of the Snake River, including the Jackson Hole area.[68] In 1810, Andrew Henry, along with a party of fur trappers, discovered the Henrys Fork of the Snake River, which is now named after him. Donald Mackenzie sailed the lower Snake River in 1811, and later explorers included Wilson Price Hunt of the Astor Expedition (who gave the river the name "Mad River"),[69] Ramsay Crooks, Francisco Payelle, John Grey, Thyery Goddin, and many others after the 1830s.[68] Many of these later explorers were original members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had returned to map and explore the area in greater detail. Even later, American fur trappers scouted the area for beaver streams, but Canadian trappers from the British Hudson's Bay Company were by now a major competitor.

The Hudson's Bay Company first sent fur trappers into the Snake River watershed in 1819. The party of three traveled into the headwaters of the Owyhee River, a major southern tributary of the Snake, but disappeared.[70] Meanwhile, as American fur trappers kept coming to the region, the Hudson's Bay Company ordered the Canadian trappers to kill as many beavers as they could, eventually nearly eradicating the species from the Snake River watershed, under the "rationale [that] if there are no beavers, there will be no reason for the Yanks ([Americans]) to come."[70] Their goal was to eventually gain rights over the Oregon Territory, a region covering Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming (most of the present-day region called the Pacific Northwest).[71] However, the area was eventually annexed into the United States.

By the middle 19th century, the Oregon Trail had been established, generally following much of the Snake River. One crossing the trail made over the Snake River was near the present-day site of Glenns Ferry. Several years later, a ferry was established at the site, replacing the old system where pioneers had to ford the wide, powerful and deep Snake. Another place where pioneers crossed the Snake was further upstream, at a place called "Three Island Crossing", near the mouth of the Boise River. This area has a group of three islands (hence the name) that splits the Snake into four channels each about 200 feet (61 m) wide. Some emigrants chose to ford the Snake and proceed down the west side and recross the river near Fort Boise into Hells Canyon, continue down the drier east side into the gorge, or float the Snake and Columbia to the Willamette River, the destination of the Oregon Trail. The reason for the Three Island Crossing was the better availability of grass and water access.[72] Numerous ferries have provided crossings of the upper Snake from the Brownlee Ferry at the head of Hell's Canyon[73] to Menor's Ferry,[74] which operates today at Moose, Wyoming. Sophistication varied from reed boats pulled by Indians on horse back at Snake Fort, Fort Boise, as described by Narcissa Whitman[75] in 1836 to an electric operated ferry, the Swan Falls Ferry,[76] at Swan Falls Dam of the early 20th century.

One contemporary diarist crossing near Salmon Falls complains of "exorbitant" fees at the crossings that were a "constant drain" on the traveler's purse. She writes that this particular route was controlled by Mormons who had "built bridges where they were not needed-most unmercifully fleecing the poor emigrants". The diarist expresses regret at having made the crossing describing the landscape as "desolate country". Another writer similarly notes several days travel through "a desert so desolate and rocky that we almost regretted that we had not continued on the south side of that stream".[77]

Steamboats

Unlike the Columbia River, it was far more difficult for steamboats to navigate on the Snake. The Columbia River drops 2,690 feet (820 m) from source to mouth, while the Snake drops over 8,500 feet (2,600 m) in elevation over a length more than 200 miles (320 km) shorter. Still, from the 1860s to the 1940s, steamboats traveled on the Snake River from its mouth at the Columbia River to near the mouth of the Imnaha River in lower Hells Canyon.[78] However, most of the steamboats only sailed from the river's mouth to Lewiston, located at the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers.[79] This stretch of the river is the easiest to navigate for watercraft since it has the least elevation change, although it still contained over 60 sets of rapids.[80]

Passenger and freight service downstream of Lewiston lasted throughout the late 19th century and persisted until the introduction of railroads in the Palouse Hills grain-growing region and ultimately, the construction of dams on the lower Snake to facilitate barge traffic, which caused the demise of both the steamboats and the railroad. Lewiston, 140 miles (230 km) from the confluence of the Snake and Columbia and 465 miles (748 km) from the mouth of the Columbia on the Pacific Ocean, became connected with Portland and other Pacific ports via steamboat service from the mouth of the Snake through the Columbia River Gorge.[81] A commonly traveled route was from Wallula, Washington, 120 miles (190 km) downstream of the Snake River's mouth, upstream to Lewiston.[82] The Oregon Steam Navigation Company launched the Shoshone at Fort Boise in 1866 which provided passenger and freight service on the upper Snake for the Boise and Owyhee mines.[83]

By the 1870s, the OSN Company, owned by the Northern Pacific Railroad, was operating seven steamboats for transporting wheat and grain from the productive Palouse region along the Snake and Columbia to lower Columbia River ports. These boats were the Harvest Queen, John Gates, Spokane, Annie Faxon, Mountain Queen, R.R. Thompson, and Wide West, all of which were built on the Columbia River.[84] However, there were more resources along the Snake River than wheat and grain. In the 1890s, a huge copper deposit was discovered at Eureka Bar in Hells Canyon. Several ships were built specifically to transport ore from there to Lewiston: these included Imnaha, Mountain Gem, and Norma.[85] In 1893 the Annie Faxon suffered a boiler explosion and sank on the Snake below Lewiston.[79][86]

River modifications

Dams

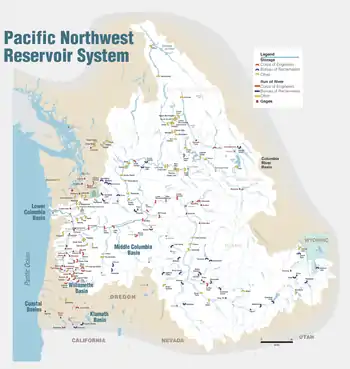

A total of twenty dams have been constructed along the Snake River for a multitude of different purposes, from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to its mouth on Lake Wallula, the reservoir formed behind McNary Dam on the Columbia River. Dams on the Snake can be grouped into three major categories.

- From its headwaters to the beginning of Hells Canyon, many small dams block the Snake to provide irrigation water. Between the headwaters and Hells Canyon, the first dam on the Snake, Swan Falls Dam, was built in 1901.

- In Hells Canyon, a cascade of dams produce hydroelectricity from the river's steep fall over a comparatively short distance.

- Finally, a third cascade of dams, from Hells Canyon to the mouth, facilitates navigation. Many different government and private agencies have worked to build dams on the Snake River, which now serve an important purpose for people living in the drainage basin and trade of agricultural products to Pacific seaports.

The Minidoka Irrigation Project of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, created with the passage of the Reclamation Act of 1902, involved the diversion of Snake River water into the Snake River Plain upstream of Shoshone Falls in order to irrigate approximately 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) in the Snake River Plain and store 4,100,000 acre-feet (5.1 km3) of water in Snake River reservoirs.[87] The first studies for irrigation in the Snake River Plain were conducted by the United States Geological Survey in the late 19th century, and the project was authorized on April 23, 1904.[88] The first dam constructed for the project was Minidoka Dam in 1904; its power plant began operating in 1909, producing 7 MW of electricity. This capacity was revised to 20 MW in 1993.[89]

Jackson Lake Dam, far upstream in Wyoming's Grand Teton National Park, was built in 1907 to raise Jackson Lake for providing additional water storage in dry years. American Falls Dam, upstream of Minidoka, was completed in 1927 and replaced in 1978.[88] As the dams were constructed above Shoshone Falls, the historical upriver limit of salmon and also a total barrier to boats and ships, no provisions were made for fish passage or navigation. Several other irrigation dams were also built - including Twin Falls Dam and Palisades Dam.

The Hells Canyon Project was built and maintained by Idaho Power starting in the 1940s and was the second of the three major water projects on the river. The three dams of the project, Brownlee Dam, Oxbow Dam and Hells Canyon Dam, are located in upper Hells Canyon. All three dams are primarily for power generation and flood control and do not have fish passage or navigation locks.[90]

Brownlee Dam, the most upriver dam, was constructed in 1959 and generates 728 megawatts (MW). Oxbow Dam, the second dam in the project, was built in 1961 and generates 220 MW. The dam was named for a 3-mile-wide (4.8 km) bend in the Snake River, shaped like an oxbow. Hells Canyon Dam was the last and most downriver of the three. It was constructed in 1967 and generates 450 MW.[41]

Downriver of Hells Canyon is the Lower Snake River Project, authorized by the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1945 for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to create a navigable channel on the Snake River from its mouth to the beginning of Hells Canyon.[91] These dams are, from upstream to downstream: Lower Granite Lock and Dam, Little Goose Lock and Dam, Lower Monumental Lock and Dam, and Ice Harbor Lock and Dam. Dredging work was also done throughout the length of the navigation channel to facilitate ship passage. These dams form a cascade of reservoirs with no stretches of free-flowing river in between. Immediately below Ice Harbor Dam is Lake Wallula, formed by the construction of the McNary Dam on the Columbia River. (McNary Dam is not part of the Lower Snake River Project.) Above Lower Granite Dam, the river channel from Lewiston to Johnson Bar, just below Hells Canyon, is also maintained for jet-boats as this section is too rugged for ships.[92]

These dams have been proposed for removal, and if they were to be removed, it would be the largest dam removal project ever undertaken in the United States.[93] The removal has been proposed on the grounds that it would restore salmon runs to the lower Snake River and the Clearwater River and other smaller tributaries.[94] Idaho's Snake river once teemed with sockeye salmon. However, there are almost no wild sockeye salmon left in the river due to a number of factors. The confidential bundle of obligations assumed by the United States government in response to litigants contesting the administration of the lower Snake River dams is perceived by stakeholders in Pacific Northwest agriculture as a transformative development. This covert agreement is anticipated to confer heightened influence upon proponents of dam breaching, notably impacting the trajectory of the Columbia-Snake river system in the foreseeable future.[95]

Sockeye Salmon are reduced in number on this river that runs through three different states and is over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) long. Salmon swimming upstream in this river are faced with predators and dams.[96] The Snake River has fifteen dams and is extremely difficult for salmon to access because of hydroelectric dams. Hells Canyon Dam blocks passage to the entire upper Snake River.

Between 1985 and 2007, only an average of 18 sockeye salmon returned to Idaho each year. Serious conservation efforts by wildlife biologists and fish hatcheries have captured the few remaining wild sockeye salmon, collected their sperm and eggs, and in a laboratory, have them spawn. Instead of spawning naturally, these sockeye begin their lives in an incubator in a hatchery. These baby salmon then are transported by ship, bypassing the dams. (The dams can hurt juvenile baby sockeye salmon with their powerful tides and currents, which suck the baby salmon down.) Another conservation effort that has helped the salmon recover is the destruction of old, outdated dams, such as the Lewiston Dam on the Clearwater River, a tributary of the Snake. After destroying the dam, salmon populations noticeably recovered.[97]

Another recovery method carried out by the Corps of Engineers is called Fish Transportation. Since many juvenile salmon perish at each dam while swimming out to the ocean, ships filter and collect these salmon smolts by size and take them out to the ocean, where they can be guaranteed to make it alive to saltwater.[98] This method raises controversy to the effectiveness and costs, since this method is extremely expensive, almost costing $15 million. Another possible upstream passage solution is the Whooshh Fish Transport System. Engineers at Whooshh Innovations have developed a fish passage system that allows for the safe and timely transportation of fish over barriers through a flexible tube system via volitional entry into the system.[99]

Overall, these combined efforts have had good success. In the summer of 2006, the Snake River reportedly only had 3 sockeye salmon that returned to their spawning grounds. In the summer of 2013, more than 13,000 sockeye salmon returned to the spawning grounds.[100]

Navigation

In the 1960s and 1970s the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built four dams and locks on the lower Snake River to facilitate shipping. The lower Columbia River has likewise been dammed for navigation. Thus a deep shipping channel through locks and slackwater reservoirs for heavy barges exists from the Pacific Ocean to Lewiston, Idaho. Most barge traffic originating on the Snake River goes to deep-water ports on the lower Columbia River, such as Portland. Grain, mostly wheat, is the main product shipped from the Snake, and nearly all of it is exported internationally from the lower Columbia River ports.

The shipping channel is authorized to be at least 14 feet (4 m) deep and 250 feet (76 m) wide. Where river depths were less than 14 feet (4 m), the shipping channel has been dredged in most places. Dredging and redredging work is ongoing and actual depths vary over time.[101] With a channel about 5 feet (1.5 m) deeper than the Mississippi River system, the Columbia and Snake rivers can float barges twice as heavy.[102] Agricultural products from Idaho and eastern Washington are among the main goods transported by barge on the Snake and Columbia rivers. Grain, mainly wheat, accounts for more than 85% of the cargo barged on the lower Snake River. In 1998, over 123,000,000 US bushels (4.3×109 L; 980,000,000 US dry gal; 950,000,000 imp gal) of grain were barged on the Snake. Before the completion of the lower Snake dams, grain from the region was transported by truck or rail to Columbia River ports around the Tri-Cities. Other products barged on the lower Snake River include peas, lentils, forest products, and petroleum.[101]

Biology

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) divides the Snake River's watershed into two freshwater ecoregions: the "Columbia Unglaciated" ecoregion and the "Upper Snake" ecoregion. Shoshone Falls marks the boundary between the two. The WWF placed the ecoregion boundary about 50 kilometres (31 mi) downriver from Shoshone Falls in order to include the Big Wood River (the main tributary of the Malad River) in the Upper Snake ecoregion, because the Wood River is biologically distinct from the rest of the downriver Snake. Shoshone Falls has presented a total barrier to the upstream movement of fish for 30,000 to 60,000 years. As a result, only 35% of the fish fauna above the falls, and 40% of the Wood River's fish fauna, are shared with the lower Snake River.[103][104]

The Upper Snake freshwater ecoregion includes most of southeastern Idaho and extends into small portions of Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada, including major freshwater habitats such as Jackson Lake. Compared to the lower Snake River and the rest of the Columbia River's watershed, the Upper Snake ecoregion has a high level of endemism, especially among freshwater molluscs such as snails and clams. There are at least 21 snail and clam species of special concern, including 15 that appear to exist only in single clusters. There are 14 fish species found in the Upper Snake region that do not occur elsewhere in the Columbia's watershed, but which do occur in Bonneville freshwater ecoregion of western Utah, part of the Great Basin and related to the prehistoric Lake Bonneville. The Wood River sculpin (Cottus leiopomus) is endemic to the Wood River. The Shoshone sculpin (Cottus greenei) is endemic to the small portion of the Snake River between Shoshone Falls and the Wood River.[105]

The Snake River below Shoshone Falls is home to thirty-five native fish species, of which twelve are also found in the Columbia River and four of which are endemic to the Snake: the relict sand roller (Percopsis transmontana) of the family Percopsidae, the shorthead sculpin (Cottus confusus), the margined sculpin (Cottus marginatus), and the Oregon chub (Oregonichthys crameri). The Oregon chub is also found in the Umpqua River and nearby basins. The lower Snake River also supports seven species of Pacific salmon and trout (Oncorhynchus). There are also high, often localized levels of mollusc endemism, especially in Hells Canyon and the basins of the Clearwater River, Salmon River, and middle Snake River. The mollusc richness extends into the lower Columbia River and tributaries such as the Deschutes River.[105]

Animals

Aside from aquatic species, much of the Snake River watershed supports larger animals including numerous species of mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles. Especially in the headwaters and the other mountainous areas strewn throughout the watershed, the gray wolf, grizzly bear, wolverine, mountain lion and Canada lynx are common. It has been determined that there are 97 species of mammals in the upper part of the Snake River, upstream from the Henrys Fork confluence.[13] Pronghorn and bighorn sheep are common in the area drained by the "lost streams of Idaho", several rivers and large creeks that flow south from the Rocky Mountains and disappear into the Snake River Aquifer. About 274 bird species, some endangered or threatened, use the Snake River watershed, including bald eagle, peregrine falcon, whooping crane, greater sage-grouse, and yellow-billed cuckoo. Barrow's goldeneye are a species of bird that occurs commonly along the lower section of the Snake River.[13]

Ten amphibian and twenty species of reptiles inhabit the upper Snake River's wetland and riparian zones. Several species of amphibians are common in the "lost streams" basin and the northeasternmost part of the Snake River watershed, including the inland tailed frog, northern leopard frog, western toad, Columbia spotted frog, long-toed salamander, spadefoot toad.[13] However, in the lower and middle portions of the Snake River watershed, several native species have been severely impacted by agriculture practices and the resulting non-native species supported by them. Introduced birds include the gray partridge, ring-necked pheasant, and chukar. Other non-native species include the bullfrog, brown-headed cowbird, and European starling, attracted by the construction of cities and towns.[106]

Plants

The Snake River watershed includes a diversity of vegetation zones both past and present.[13] A majority of the watershed was once covered with shrub-steppe grassland, most common in the Snake River Plain and also the Columbia Plateau in southeastern Washington. Riparian zones, wetlands and marshes once occurred along the length of the Snake River and its tributaries. In higher elevations, conifer forests, of which ponderosa pine is most common, dominate the landscape. The basin ranges from semi-desert to alpine climates, providing habitat for hundreds of species of plants. In the lowermost part of the watershed, in southeastern Washington, the Snake River is surrounded by an area called the Columbia Plateau Ecoprovince, which is now mostly occupied by irrigated farms. The rest of the Plateau area is characterized by low hills, dry lakes, and an arid, nearly desert climate.[106]

The headwaters of the Snake River and the high mountains elsewhere in the watershed were historically heavily forested. These include aspen, Douglas fir, and spruce fir, comprising about 20% of the historic watershed. At the base of mountains and in the Lost River basin, sagebrush was and is the predominant vegetation cover. Because of deforestation, up to one quarter of the forests have been taken over by sagebrush, leaving the remaining forests to cover about 15% of the watershed. However, the lodgepole pine has increased in number, taking over historic stands of other conifers. There are also up to 118 species of rare or endemic plants that occur in the Snake River watershed.[13]

Salmon and other anadromous fish

The Snake River was once one of the most important rivers for the spawning of anadromous fish—which are hatched in the headwaters of rivers, live in the ocean for most of their lives, and return to the river to spawn—in the United States.[107][108] The river supported species including chinook salmon, coho salmon, and sockeye salmon, as well as steelhead, white sturgeon, and Pacific lamprey. It is known that before the construction of dams on the river, there were three major chinook salmon runs in the Snake River; in the spring, summer and fall, totaling about 120,000 fish, and the sockeye salmon run was about 150,000. The historical barrier to fish migration on the Snake River was Shoshone Falls, a waterfall that occurs as the Snake River passes through the Snake River Plain.[107]

Since the early 20th century, when Swan Falls Dam was constructed on the middle Snake River upstream of Hells Canyon, the fifteen dams and reservoirs on the river have posed an increasing problem for migrating salmon. Agricultural lands and their resulting runoff have also had a significant impact on the success rate of migrating fish. Salmon can travel up the Snake River as far as Hells Canyon Dam, using the fish passage facilities of the four lower Snake River dams, leaving the Clearwater, Grande Ronde and Salmon river to sustain spawning salmon. Rising in several forks in the Clearwater Mountains of central Idaho, the Clearwater and Salmon River watersheds are nearly undeveloped with the enormous exception of Dworshak Dam on the North Fork Clearwater River. The watershed of the Grande Ronde in northeastern Oregon is also largely undeveloped. The four reservoirs formed by the lower Snake River dams—Lake Sacagawea, Lake Herbert G. West, Lake Bryan, and Lower Granite Lake—have also formed problems, as the downstream current in the pools is often not enough for the fish to sense, confusing their migration routes.[19][109]

At the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater Rivers, young salmon that swim down from spawning gravels in the headwaters of the Clearwater River often delay their migrations because of a significant temperature difference. (Prior to the removal of Lewiston Dam on the main Clearwater and Grangeville Dam on the South Fork Clearwater, the Clearwater was completely unusable by migrating salmon.[110]) Agricultural runoff and water held in reservoirs higher upstream on the Snake warm its waters as it flows through the Snake River Plain, so as the Snake meets the Clearwater, its average temperature is much higher. Directly below the confluence, the river flows into Lower Granite Lake, formed by Lower Granite Dam, the uppermost dam of the Lower Snake River Project. Paradoxically, the combination of these factors gives the young salmon further time to grow and to feed in Lower Granite Lake, so when they begin the migration to the Pacific Ocean, they often have a higher chance at survival, compared to those salmon who migrate to the ocean earlier.[109]

Lower Snake River dam removal

A controversy has erupted since the late 20th century over the four lower Snake River dams, with the primary argument being that removing the dams would allow anadromous fish to reach the lower Snake River tributaries—the Clearwater River, the Tucannon River and the Grande Ronde River—and spawn in much higher numbers. However, removal of the dams has been fiercely opposed by some groups in the Pacific Northwest.[111] Because much of the electricity in the Northwest comes from dams, removing the four dams would create a hole in the energy grid that would not be immediately replaceable.[112] Navigation on the lower Snake would also suffer, as submerged riffles, rapids and islands would be exposed by the removal of the dams. Irrigation pumps for fields in southeastern Washington would also have to reach further to access the water of the Snake River. However, proponents for restoring salmon runs by dam removal argue that the power is replaceable, that the grain transportation system could be replaced by railroads, and that only one of the four reservoirs supplies irrigation water. Irrigators in the Snake River Plain would likely need to allow less water into the Snake River during low flow in order to create a current in the four lower reservoirs, and recreation and tourism would likely benefit.[113]

In a late 2022 opinion piece published in The Spokesman-Review, Trout Unlimited scientist Helen Neville wrote an up-to-date summary of the problems the dams cause for salmon.

"Scientific analysis has repeatedly pointed toward the negative impacts of how the dams impede juvenile and adult fish migration, heat the water to deadly temperatures, inundate 140 miles of mainstem spawning and rearing habitat, and provide ideal conditions for expanding populations of predators feasting on salmon and steelhead smolts."[114]

Furthermore, well-meaning efforts to support salmon with hatcheries are insufficiently successful. "Billions of dollars have been spent producing hatchery salmon and steelhead to prop up fisheries, as Congressionally mandated to mitigate the population losses caused by the dams, and it is not working to recover wild fish."[114]

In opposing breaching, the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) cites the value of the four lower Snake River dams in generating low-cost, zero-carbon electricity, and the substantial financial cost of replacing their output. Their evidence for this is in a report by energy consulting firm Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. (E3).[115] The report includes complicated scenarios, but a consideration of all of the technologies potentially involved in replacing the dams' electricity generation is needed for the public to assess whether the costs are bearable or not for the sake of saving salmon.

The sum capacity of the four dams is 3,483 MW maximum power output, with approximately 2,300 MW of firm peaking capability to avoid power shortages during extreme cold weather events.[116] The dams also provide operational flexibility in changing power output with short-term reserves plus multi-hour ramping / renewable integration capabilities.[117] Their approximately 900 MW average hourly output is enough to support about 450,000 households.

Replacement of the dams would require "a combination of renewable generation (wind), 'clean firm' resources (such as dual fuel natural gas plus hydrogen plants, advanced nuclear, or gas with carbon capture and storage), and energy efficiency. Battery storage cannot cost-effectively replace hydro capacity in the Northwest due to charging limitations during energy shortfall events."[116]

"Replacement power would cost several times as much as the lower Snake River dams costs," according to the publication.[118]

Modeling studies calculated the costs of replacing the power from the dams comparing several scenarios, favoring two "deep decarbonization" ones. Deep decarbonization was defined as "zero carbon emissions by 2045 [and] high electrification of buildings, transportation, and industry to reduce carbon emissions in other sectors."[119] Two scenarios that aimed for deep decarbonization compared costs when adding only baseline technology capabilities, with costs when at least one "emerging" technology substituted for some of the baseline technology.

Baseline technologies were "solar, wind, battery plus pumped storage, energy efficiency, demand response, [and] dual fuel natural gas plus hydrogen combustion plants."[120]

"Emerging technologies such as hydrogen, advanced nuclear, and carbon capture can limit the cost of replacement resources to meet a zero emissions electric system, but the pace of their commercialization is highly uncertain."[121] For reducing cost, the study particularly favored adding new small modular nuclear reactors as a cheaper alternative to baseline technologies.[122]

With at least one emerging technology in a deep decarbonization scenario, net present value annual costs of replacing the services of the dams was modeled to be $415 million in 2035 to $428 million in 2045. This would lead to public power retail costs increasing by 8% (on average an extra $100 per year per household) in higher bills by 2045.

In a purely baseline technologies deep decarbonization scenario, extra annual costs would range from $496 million in 2035 to $860 million in 2045, leading to 18% higher bills ($230 more per year) by 2045.

Other scenarios were within the same cost range, except for deep decarbonization with no new combustion, which would be much more costly because of difficulties in creating firm capability solely with wind and solar power.[123]

Tributaries

The Snake River has over 20 major tributaries, most of which are in the mountainous regions of the basin. The Salmon River is the longest tributary and drains the largest area, though the Clearwater River carries a greater volume of water. Many of the rivers that flow into the Snake River Plain from the north sink into the Snake River Aquifer, but still contribute their water to the river. Aside from rivers, the Snake is fed by many significant springs, many of which arise from the aquifer on the west side of the plain.[13]

| Name | Length | Watershed size | Bank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source to Wyoming-Idaho Border | |||

| Heart River | 8+1⁄2 mi (14 km) | Right | |

| Lewis River | 12 mi (19 km) | Right | |

| Gros Ventre River | 642 sq mi (1,660 km2) | Left | |

| Hoback River | 55 mi (89 km) | 600 sq mi (1,600 km2) | Left |

| Greys River | 65 mi (105 km) | 800 sq mi (2,100 km2) | Left |

| Salt River | 70 mi (113 km) | 890 sq mi (2,300 km2) | Left |

| Snake River Plain to Hells Canyon | |||

| Henrys Fork (Snake River) | 110 mi (177 km) | 3,212 sq mi (8,320 km2) | Right |

| Portneuf River | 96 mi (154 km) | 1,329 sq mi (3,440 km2) | Left |

| Raft River | 1,506 sq mi (3,900 km2) | Left | |

| Malad River | 11+1⁄2 mi (19 km) | 3,000 sq mi (7,800 km2) | Right |

| Salmon Falls Creek | 218 mi (351 km) | 2,082 sq mi (5,390 km2) | Left |

| Bruneau River | 3,305 sq mi (8,560 km2) | Left | |

| Owyhee River | 280 mi (451 km) | 11,049 sq mi (28,620 km2) | Left |

| Boise River | 75 mi (121 km) | 4,100 sq mi (11,000 km2) | Right |

| Malheur River | 165 mi (266 km) | 4,700 sq mi (12,000 km2) | Left |

| Payette River | 62 mi (100 km) | 3,240 sq mi (8,400 km2) | Right |

| Hells Canyon | |||

| Weiser River | 90 mi (145 km) | 1,660 sq mi (4,300 km2) | Right |

| Burnt River | 50 mi (80 km) | Left | |

| Salmon River | 425 mi (684 km) | 14,000 sq mi (36,000 km2) | Right |

| Grande Ronde River | 212 mi (341 km) | 4,000 sq mi (10,000 km2) | Left |

| Clearwater River | 80 mi (129 km) | 9,645 sq mi (24,980 km2) | Right |

| Idaho-Washington border to mouth | |||

| Tucannon River | 70 mi (113 km) | 503 sq mi (1,300 km2) | Left |

| Palouse River | 140 mi (225 km) | 3,303 sq mi (8,550 km2) | Right |

See also

- Angling in Yellowstone National Park

- Fishes of Yellowstone National Park

- List of crossings of the Snake River

- List of tributaries of the Columbia River

- List of rivers of Idaho

- List of longest streams of Idaho

- List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)

- List of longest streams of Oregon

- List of National Wild and Scenic Rivers

- List of rivers of Oregon

- List of Washington rivers

- List of Wyoming rivers

- List of rivers in the United States

- Lost streams of Idaho

References

- 1 2 Snake River Source (Map). CalTopo. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ the road atlas. p. 109. 2009. ISBN 0-528-94200-X.

- 1 2 3 "Snake River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ Google Earth elevation for GNIS mouth coordinates. Retrieved on April 29, 2007

- 1 2 United States Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 4, 2011

- 1 2 "Boundary Descriptions and Names of Regions, Subregions, Accounting Units and Cataloging Units". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Snake River below Ice Harbor Dam, WA" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1963–2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- 1 2 "Ice Harbor Lock and Dam". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 1915–1972. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "National Wild and Scenic Rivers System". rivers.gov. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- 1 2 Kammerer, J.C. (May 1990). "Largest Rivers in the United States". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Snake River - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Snake River Tributary Basins". Idaho Water Resources Research Institute at Idaho Falls. University of Idaho, Idaho Falls. Archived from the original on April 23, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Upper Snake Province Assessment" (PDF). Northwest Watershed Council. May 28, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- 1 2 "Eastern Snake River Plain Surface and Ground Water Interaction". Idaho Water Resources Research Institute at Idaho Falls. University of Idaho, Idaho Falls. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 United States Geological Survey. "United States Geological Survey Topographic Maps". TopoQuest. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 USGS Topo Maps for United States (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. ACME Mapper. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Shoshone Falls". South Central Idaho Virtual Tour. College of Southern Idaho. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ↑ "I.B. Perrine Bridge". Structurae. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- 1 2 Harrison, John (October 31, 2008). "Hells Canyon Dam". Columbia River History. Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- 1 2 Link, Paul. "Neogene Snake River Plain-Yellowstone Volcanic Province". Digital Geology of Idaho. Idaho State University Department of Geosciences. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ↑ Staub, Kristen; Link, Paul. "Geology, Age and Extent of the Columbia River Basalts". Digital Geology of Idaho. Idaho State University. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ↑ "The Story Begins". Creation of the Teton Landscape: The Geologic Story of Grand Teton National Park. National Park Service. January 19, 2007. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Hulls Gulch National Recreation Trail". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Lake Bonneville and the Bonneville Flood". USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory, U.S. National Park Service. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Lake Bonneville and the Bonneville Flood". Huge Floods. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- 1 2 Orr, Elizabeth L.; William N. Orr (1996). Geology of the Pacific Northwest. McGraw-Hill. pp. 241–248. ISBN 0-07-048018-4.

- 1 2 "Geology of Hells Canyon". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011.

- ↑ "The Lake Bonneville Flood". Digital Atlas of Idaho. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ↑ "About the Floods". Ice Age Floods Institute. August 18, 2008. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Channeled Scablands: Overview". Department of Geography and Geology. University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Idaho's treasure; the Eastern Snake River Plain Aquifer" (PDF). State of Idaho Oversight Monitor. Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. May 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Richard P. (2004). "Geologic Setting of the Snake River Plain Aquifer and Vadose Zone" (PDF). Vadose Zone Journal. GeoScienceWorld. 3 (1): 47–58. Bibcode:2004VZJ.....3...47S. doi:10.2113/3.1.47. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Low, W. H. (1991). "Upper Snake River Basin". National Water Quality Assessment Program. United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr91165. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Snake River Plain Regional Aquifer System". Ground Water Atlas of the United States: Idaho, Oregon, Washington. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ The percentage is calculated by adding the discharge at Priest Rapids Dam on the Columbia to the discharge at Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake. Priest Rapids is the closest USGS gauge upstream of the Snake confluence that has a reliable discharge record.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #12472800 on the Columbia River below Priest Rapids Dam, WA (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ↑ Upstream Columbia mileage calculated by subtracting 325 (Snake River confluence mile) from 1243 (the length of the Columbia). 325 miles (523 km) below the Snake confluence comes from river mileage markers on USGS topo maps.

- ↑ The watershed of the Columbia upstream of the Snake River confluence is 97,190 square miles (251,700 km2), just slightly smaller than that of the Snake.

- ↑ "Twin Falls, Idaho Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Snake River, Wyoming Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- 1 2 "Hydroelectric Plants". Idaho Power. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Harrison, John (October 31, 2008). "Fish passage at dams". Columbia River History. Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Watersheds (Map). Cartography by CEC, Atlas of Canada, National Atlas, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ↑ Wolf, Carissa (February 1, 2006). "Dirty Water: Ag pollution in rural wells runs deep". Boise Weekly. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Pollution of the Snake River". Ecology and Conservation. Central Washington Native Plants. Archived from the original on October 23, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Groundwater Resources". Digital Atlas of Idaho. Idaho Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on June 25, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ Ritter, William F.; Shirmohammadi, Adel (2001). Agricultural nonpoint source pollution: watershed management and hydrology. CRC Press. p. 170. ISBN 1-56670-222-4.

- ↑ Philip, Jeff (September 13, 2004). "EPA Approves Pollution Limits for Snake River-Hells Canyon". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13010065 on the Snake River above Jackson Lake at Flagg Ranch, WY (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13081500 on the Snake River near Minidoka, ID (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13094000 on the Snake River near Buhl, ID (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13269000 on the Snake River near Weiser, ID (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13290454 on the Snake River at Hells Canyon Dam, Idaho-Oregon state line (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "USGS Gage #13290454 on the Snake River near Anatone, WA (Water-Data Report 2009)" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Snake River" (PDF). Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. 38: 2. February 1964. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ↑ Gulick, Bill (1971). Snake River Country. Caxton Press. ISBN 0-87004-215-7.

- ↑ Hunger, Bill (2008). Hiking Wyoming: 110 of the State's Best Hiking Adventures (2 ed.). Globe Pequot. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-7627-3420-7.

- ↑ Summary of Western Snake River Prehistory Archived 2012-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, Digital Atlas of Idaho

- ↑ Meatte, Daniel S. (1990). "The Fremont Culture". The Prehistory of the Western Snake River Basin. Digital Atlas of Idaho. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ Meatte, Daniel S. (1990). "The Midvale Complex". Prehistory of the Western Snake River Basin. Digital Atlas of Idaho. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ↑ Tate, Cassandra (October 5, 2006), "Marmes Rockshelter", HistoryLink, Seattle: History Ink, retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ↑ Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John Arthur (1992). A guide to the Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-8061-2479-2.

- ↑ Madsen, Brigham D. (1980). The Northern Shoshoni. Caxton Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-87004-266-1.

- ↑ Madsen, Brigham D. (1996). The Bannock of Idaho. University of Idaho Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-89301-189-4.

- 1 2 Gulick, p. 17

- ↑ Lewis, Meriwether; Clark, William (2003) [1804–1806]. Moulton, Gary E. (ed.). The Lewis and Clark journals: An American epic of discovery. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-2950-X.

- ↑ Lavender, David Sievert (2001). The way to the western sea: Lewis and Clark across the continent. University of Nebraska Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-8032-8003-3.

- 1 2 "Snake River Explorers" (PDF). Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. Idaho State Historical Society. April 1992. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Gulick (Snake River Country), p. 24

- 1 2 Kaza, Roger. "Hudson's Bay Company". Engines of our Ingenuity. University of Houston. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ Gulick (Snake River Country), p. 32

- ↑ "Three Island Crossing". The Oregon Trail in Idaho. Idaho State Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ↑ Maxwell, Rebecca (October 12, 2009). "Brownlee Ferry". Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Grand Tetons, Cunningham Cabin, Nick Wilson, Menor's Ferry". Jackson Hole Photo Gallery. Wyoming Tales and Trails. Archived from the original on August 25, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ Eells, Myron (1909). Marcus Whitman, pathfinder and patriot. Alice Harriman Company. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Snake River Ferries" (PDF). Idaho State Historical Society. October 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Hines, Celinda Elvira (2008). Seven Months to Oregon: 1853 Diaries, Letters and Reminiscent Accounts. Patrice Press. ISBN 978-0803272958.

- ↑ Gulick, Bill (2004). Steamboats on Northwest Rivers. Caxton Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-87004-438-9.

- 1 2 Dougherty, Phil (April 9, 2006). "Steamers on the Lower Snake". HistoryLink.org. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Recreation on a Free-Flowing Lower Snake River" (PDF). American Rivers. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ↑ Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, p. xiii

- ↑ Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, p. 93

- ↑ Carrey, John (1979). Snake River of Hells Canyon. Backeddy Books. pp. 32–42. ISBN 0-9603566-0-6.

- ↑ Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, p. 122

- ↑ Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, p. 162

- ↑ Williamson, Darcy (1997). River Tales of Idaho. Caxton Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-87004-378-1.

- ↑ Fiege, Mark (1999). Irrigated Eden: the making of an agricultural landscape in the American West. University of Washington Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-295-97757-4.

- 1 2 "Minidoka Project". Pacific Northwest Dams & Projects. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. June 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Minidoka Project History". Pacific Northwest Region Dams & Projects. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. February 9, 2008. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Hells Canyon". Idaho Power. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Lewiston, Idaho to Johnson Bar". USACE Walla Walla District. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. September 30, 1994. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Joshi, Pratik (August 1, 2009). "Bill opens possibility of Lower Snake River dam removal". Tri-City Herald.

- ↑ "Analysis of Snake River dam removal has deficiencies, economists report". Northwest Power and Conservation Council. March 14, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ Weaver, Matthew (December 5, 2023). "Ag groups: Snake River dam deal 'leaves farmers behind'". Capital Press.

- ↑ Golden, Hallie (June 9, 2021). "Salmon face extinction throughout the US west. Blame these four dams". the Guardian. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ↑ ""Northwest Fisheries Science Center." Once Nearly Extinct, Endangered Idaho Sockeye Regaining Fitness Advantage -. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2016". Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.