| Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy | |

|---|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 05.2 |

| MedlinePlus | 007291 |

Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy (ETS) is a surgical procedure in which a portion of the sympathetic nerve trunk in the thoracic region is destroyed.[1][2] ETS is used to treat excessive sweating in certain parts of the body (focal hyperhidrosis), facial blushing, Raynaud's disease and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. By far the most common complaint treated with ETS is sweaty palms (palmar hyperhidrosis). The intervention is controversial and illegal in some jurisdictions. Like any surgical procedure, it has risks; the endoscopic sympathetic block (ESB) procedure and those procedures that affect fewer nerves have lower risks.

Sympathectomy physically destroys relevant nerves anywhere in either of the two sympathetic trunks, which are long chains of nerve ganglia located bilaterally along the vertebral column (a localisation which entails a low risk of injury) responsible for various important aspects of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Each nerve trunk is broadly divided into three regions: cervical (neck), thoracic (chest), and lumbar (lower back). The most common area targeted in sympathectomy is the upper thoracic region, that part of the sympathetic chain lying between the first and fifth thoracic vertebrae.

Indications

The most common indications for thoracic sympathectomy are focal hyperhidrosis (that specifically affects the hands and underarms), Raynaud syndrome, and facial blushing when accompanied by focal hyperhidrosis. It may also be used to treat bromhidrosis,[3] although this usually responds to non-surgical treatments,[4] and sometimes people with olfactory reference syndrome present to surgeons requesting sympathectomy.[5]

There are reports of ETS being used to achieve cerebral revascularization for people with moyamoya disease,[6] and to treat headaches, hyperactive bronchial tubes,[7] long QT syndrome,[8][9][10] social phobia,[11] anxiety,[12] and other conditions.

Surgical procedure

ETS involves dissection of the main sympathetic trunk in the upper thoracic region of the sympathetic nervous system, irreparably disrupting neural messages that ordinarily would travel to many different organs, glands and muscles. It is via those nerves that the brain is able to make adjustments to the body in response to changing conditions in the environment, fluctuating emotional states, level of exercise, and other factors to maintain the body in its ideal state (see homeostasis).

Because these nerves also regulate conditions like excessive blushing or sweating, which the procedure is designed to eliminate, the normative functions these physiological mechanisms perform will be disabled or significantly impaired by sympathectomy.

There is much disagreement among ETS surgeons about the best surgical method, optimal location for nerve dissection, and the nature and extent of the consequent primary effects and side effects. When performed endoscopically as is usually the case, the surgeon penetrates the chest cavity making multiple incisions about the diameter of a straw between ribs. This allows the surgeon to insert the video camera (endoscope) in one hole and a surgical instrument in another. The operation is accomplished by dissecting the nerve tissue of the main sympathetic chain.

Another technique, the clamping method, also referred to as 'endoscopic sympathetic blockade' (ESB) employs titanium clamps around the nerve tissue, and was developed as an alternative to older methods in an unsuccessful attempt to make the procedure reversible. Technical reversal of the clamping procedure must be performed within a short time after clamping (estimated at a few days or weeks at most), and a recovery, evidence indicates, will not be complete.

Physical, mental and emotional effects

Sympathectomy works by disabling part of the autonomic nervous system (and thereby disrupting its signals from the brain), through surgical intervention, in the expectation of removing or alleviating the designated problem. Many non-ETS doctors have found this practice questionable chiefly because its purpose is to destroy functionally disordered, yet anatomically typical nerves.[13]

Exact results of ETS are impossible to predict, because of considerable anatomic variation in nerve function from one patient to the next, and also because of variations in surgical technique. The autonomic nervous system is not anatomically exact and connections might exist which are unpredictably affected when the nerves are disabled. This problem was demonstrated by a significant number of patients who underwent sympathectomy at the same level for hand sweating, but who then presented a reduction or elimination of feet sweating, in contrast to others who were not affected in this way. No reliable operation exists for foot sweating except lumbar sympathectomy, at the opposite end of the sympathetic chain.

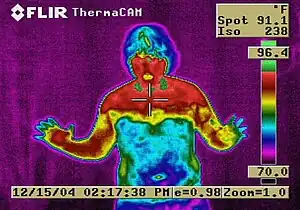

Thoracic sympathectomy will change many bodily functions, including sweating,[14] vascular responses,[15] heart rate,[16] heart stroke volume,[17][18] thyroid, baroreflex,[19] lung volume,[18][20] pupil dilation, skin temperature and other aspects of the autonomic nervous system, like the essential fight-or-flight response. It reduces the physiological responses to strong emotions, such as fear and laughter, diminishes the body's physical reaction to both pain and pleasure, and inhibits cutaneous sensations such as goose bumps.[14][18][21]

A large study of psychiatric patients treated with this surgery showed significant reductions in fear, alertness and arousal.[22] Arousal is essential to consciousness, in regulating attention and information processing, memory and emotion.[23]

ETS patients are being studied using the autonomic failure protocol headed by David Goldstein, M.D. Ph.D., senior investigator at the U.S National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He has documented loss of thermoregulatory function, cardiac denervation, and loss of vasoconstriction.[24] Recurrence of the original symptoms due to nerve regeneration or nerve sprouting can occur within the first year post surgery. Nerve sprouting, or abnormal nerve growth after damage or injury to the nerves can cause other further damage. Sprouting sympathetic nerves can form connections with sensory nerves, and lead to pain conditions that are mediated by the SNS. Every time the system is activated, it is translated into pain. This sprouting and its action can lead to Frey's syndrome, a recognized after effect of sympathectomy, when the growing sympathetic nerves innervate salivary glands, leading to excessive sweating regardless of environmental temperature through olfactory or gustatory stimulation.

In addition, patients have reported lethargy, depression, weakness, limb swelling, lack of libido, decreased physical and mental reactivity, oversensitivity to sound, light and stress and weight gain (British Journal of Surgery 2004; 91: 264–269).

Risks

ETS has both the normal risks of surgery, such as bleeding and infection, conversion to open chest surgery, and several specific risks, including permanent and unavoidable alteration of nerve function. It is reported that a number of patients - 9 since 2010, mostly young women - have died during this procedure due to major intrathoracic bleeding and cerebral disruption. Bleeding during and following the operation may be significant in up to 5% of patients.[25] Pneumothorax (collapsed lung) can occur (2% of patients).[25] Compensatory hyperhidrosis (or reflex hyperhidrosis) is common over the long term.[25] The rates of severe compensatory sweating vary widely between studies, ranging from as high as 92% of patients.[26] Of those patients that develop this side effect, about a quarter in one study said it was a major and disabling problem.[27] 35% of people affected have to change their clothes several times a day as a result.[28]

A severe possible consequence of thoracic sympathectomy is corposcindosis (split-body syndrome), in which the patient feels that they are living in two separate bodies, because sympathetic nerve function has been divided into two distinct regions, one dead, and the other hyperactive.[29]

Additionally, the following side effects have all been reported by patients: Chronic muscular pain, numbness and weakness of the limbs, Horner's Syndrome, anhidrosis (inability to sweat), hyperthermia (exacerbated by anhidrosis and systemic thermoregulatory dysfunction), neuralgia, paraesthesia, fatigue and amotivationality, breathing difficulties, substantially diminished physiological/chemical reaction to internal and environmental stimuli, somatosensory malfunction, aberrant physiological reaction to stress and exertion, Raynaud’s disease (albeit a possible indication for surgery), reflex hyperhidrosis, altered/erratic blood pressure and circulation, defective fight or flight response system, loss of adrenaline, eczema and other skin conditions resulting from exceptionally dry skin, rhinitis, gustatory sweating (also known as Frey's syndrome).[1]

Other long-term adverse effects include:

- Ultrastructural changes in the cerebral artery wall induced by long-term sympathetic denervation[30]

- Sympathectomy eliminates the psychogalvanic reflex[31]

- Cervical sympathectomy reduces the heterogeneity of oxygen saturation in small cerebrocortical veins[32]

- Sympathetic denervation is one of the causes of Mönckeberg's sclerosis[33]

- T2-3 sympathectomy suppressed baroreflex control of heart rate in the patients with palmar hyperhidrosis. The baroreflex response for maintaining cardiovascular stability is suppressed in the patients who received the ETS.[19]

- Exertional heat stroke.[14]

- Morphofunctional changes in the myocardium following sympathectomy.[34]

Other side effects are the inability to raise the heart rate sufficiently during exercise with instances requiring an artificial pacemaker after developing bradycardia being reported as a consequence of the surgery.[30][35][36]

The Finnish Office for Health Care Technology Assessment concluded more than a decade ago in a 400-page systematic review that ETS is associated with an unusually high number of significant immediate and long-term adverse effects.[37]

Quoting the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare statement: "The method can give permanent side effects that in some cases will first become obvious only after some time. One of the side effects might be increased perspiration on different places on your body. Why and how this happens is still unknown. According to the research available about 25-75% of all patients can expect more or less serious perspiration on different places on their body, such as the trunk and groin area, this is Compensatory sweating".[38]

In 2003, ETS was banned in its birthplace, Sweden, due to inherent risks, and complaints by disabled patients. In 2004, Taiwanese health authorities banned the procedure on people under 20 years of age.[39]

History

Sympathectomy developed in the mid-19th century, when it was learned that the autonomic nervous system runs to almost every organ, gland and muscle system in the body. It was surmised that these nerves play a role in how the body regulates many different body functions in response to changes in the external environment, and in emotion.

The first sympathectomy was performed by Alexander in 1889.[40] Thoracic sympathectomy has been indicated for hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) since 1920, when Kotzareff showed it would cause anhidrosis (total inability to sweat) from the nipple line upwards.[14]

A lumbar sympathectomy was also developed and used to treat excessive sweating of the feet and other ailments, and typically resulted in impotence and retrograde ejaculation in men. Lumbar sympathectomy is still being offered as a treatment for plantar hyperhidrosis, or as a treatment for patients who have a bad outcome (extreme 'compensatory sweating') after thoracic sympathectomy for palmar hyperhidrosis or blushing; however, extensive sympathectomy risks hypotension.

Endoscopic sympathectomy itself is relatively easy to perform; however, accessing the nerve tissue in the chest cavity by conventional surgical methods was difficult, painful, and spawned several different approaches in the past. The posterior approach was developed in 1908, and required resection (sawing off) of ribs. A supraclavicular (above the collar-bone) approach was developed in 1935, which was less painful than the posterior, but was more prone to damaging delicate nerves and blood vessels. Because of these difficulties, and because of disabling sequelae associated with sympathetic denervation, conventional or "open" sympathectomy was never a popular procedure, although it continued to be practiced for hyperhidrosis, Raynaud's disease, and various psychiatric disorders. With the brief popularization of lobotomy in the 1940s, sympathectomy fell out of favor as a form of psychosurgery.

The endoscopic version of thoracic sympathectomy was pioneered by Goren Claes and Christer Drott in Sweden in the late 1980s. The development of endoscopic "minimally invasive" surgical techniques has decreased the recovery time from the surgery and increased its availability. Today, ETS surgery is practiced in many countries throughout the world predominantly by vascular surgeons.

See also

References

- 1 2 Cerfolio RJ, De Campos JR, Bryant AS, Connery CP, Miller DL, DeCamp MM, McKenna RJ, Krasna MJ (2011). "The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Expert Consensus for the Surgical Treatment of Hyperhidrosis". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 91 (5): 1642–8. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.105. PMID 21524489.

- ↑ "Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy". India Today. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-01-27.

- ↑ Papadopoulos SM, Dickman CA (1999). "Thoracoscopic Sympatheectomy". In Dickman CA, Rosenthal DJ, Perin NI (eds.). Thoracoscopic Spine Surgery. Theime. pp. 143–60. ISBN 978-0-86577-785-9.

- ↑ Perera E, Sinclair R (2013). "Hyperhidrosis and bromhidrosis: a guide to assessment and management" (PDF). Australian Family Physician. 42 (5): 266–9. PMID 23781522.

- ↑ Miranda-Sivelo A, Bajo-Del Pozo C, Fructuoso-Castellar A (2013). "Unnecessary surgical treatment in a case of olfactory reference syndrome". General Hospital Psychiatry. 35 (6): 683.e3–4. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.06.014. PMID 23992627.

- ↑ Suzuki J, Takaku A, Kodama N, Sato S (1975). "An Attempt to Treat Cerebrovascular 'Moyamoya' Disease in Children". Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1 (4): 193–206. doi:10.1159/000119568. PMID 1183260.

- ↑ Sung SW, Kim JS (1999). "Thoracoscopic procedures for intrathoracic and pulmonary diseases". Respirology. 4 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.1999.00146.x. PMID 10339727.

- ↑ Telaranta T (2003). "Psychoneurological applications of endoscopic sympathetic blocks (ESB)". Clinical Autonomic Research. 13: I20–1, discussion I21. doi:10.1007/s10286-003-1107-1. PMID 14673667. S2CID 45719036.

- ↑ "London Arrhythmia Centre". www.hcahealthcare.co.uk.

- ↑ Khan IA (2002). "Long QT syndrome: Diagnosis and management". American Heart Journal. 143 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1067/mhj.2002.120295. PMID 11773906.

- ↑ Telaranta T (2003). "Treatment of social phobia by endoscopic thoracic sympathicotomy". European Journal of Surgery. 164 (580): 27–32. doi:10.1080/11024159850191102. PMID 9641382.

- ↑ Pohjavaara P, Telaranta T, Väisänen E (2003). "The role of the sympathetic nervous system in anxiety: Is it possible to relieve anxiety with endoscopic sympathetic block?". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 57 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1080/08039480310000266. PMID 12745792. S2CID 28944767.

- ↑ McNaughton N (1989). Biology and emotion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-521-31938-2.

viscera sympathectomy.

- 1 2 3 4 Sihoe AD, Liu RW, Lee AK, Lam CW, Cheng LC (September 2007). "Is previous thoracic sympathectomy a risk factor for exertional heat stroke?". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 84 (3): 1025–7. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.066. PMID 17720429.

- ↑ Redisch W, Tangco FT, Wertheimer L, Lewis AJ, Steele JM, Andrews D (1957). "Vasomotor Responses in the Extremities of Subjects with Various Neurologic Lesions: I. Reflex Responses to Warming". Circulation. 15 (4): 518–24. doi:10.1161/01.cir.15.4.518. PMID 13414070. S2CID 5969475.

- ↑ Abraham P, Berthelot J, Victor J, Saumet J, Picquet J, Enon B (2002). "Holter changes resulting from right-sided and bilateral infrastellate upper thoracic sympathectomy". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 74 (6): 2076–81. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04080-8. PMID 12643398.

- ↑ Chess-Williams RG, Grassby PF, Culling W, Penny W, Broadley KJ, Sheridan DJ (1985). "Cardiac postjunctional supersensitivity to β-agonists after chronic chemical sympathectomy with 6-hydroxydopamine". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 329 (2): 162–6. doi:10.1007/BF00501207. PMID 2861571. S2CID 5855368.

- 1 2 3 Hashmonai M, Kopelman D (2003). "The pathophysiology of cervical and upper thoracic sympathetic surgery". Clinical Autonomic Research. 13: I40–4. doi:10.1007/s10286-003-1105-3. PMID 14673672. S2CID 21326458.

- 1 2 Kawamata YT, Homma E, Kawamata T, Omote K, Namiki A (2001). "Influence of Endoscopic Thoracic Sympathectomy on Baroreflex Control of Heart Rate in Patients with Palmar Hyperhidrosis". Anesthesiology. 95: A160.

- ↑ Milner P, Lincoln J, Burnstock G (1998). "The neurochemical organization of the autonomic nervous system". In Appenzeller O, Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (eds.). The autonomic nervous system. [Amsterdam, Netherlands]: Elsevier Science Publishers. pp. 110. ISBN 0-444-82812-5.

- ↑ Bassenge E, Holtz J, von Restorff W, Oversohl K (July 1973). "Effect of chemical sympathectomy on coronary flow and cardiovascular adjustment to exercise in dogs". Pflügers Archiv. 341 (4): 285–96. doi:10.1007/BF01023670. PMID 4798744. S2CID 20076364.

- ↑ Teleranta, Pohjavaara, et al. 2003, 2004

- ↑ Pohjavaara P (2004). Social Phobia: Aetiology, Course and Treatment with Endoscopic Sympathetic Block (ESB) (PDF) (Thesis). University of Oulu, Department of Psychiatry. ISBN 978-951-42-7456-5.

- ↑ Moak JP, Eldadah B, Holmes C, Pechnik S, Goldstein DS (June 2005). "Partial cardiac sympathetic denervation after bilateral thoracic sympathectomy in humans". Heart Rhythm. 2 (6): 602–9. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.03.003. PMID 15922266.

- 1 2 3 Ojimba TA, Cameron AE (2004). "Drawbacks of endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy". British Journal of Surgery. 91 (3): 264–9. doi:10.1002/bjs.4511. PMID 14991624. S2CID 15189710.

- ↑ "Find guidance".

- ↑ Furlan AD, Mailis A, Papagapiou M (2000). "Are We Paying a High Price for Surgical Sympathectomy? A Systematic Literature Review of Late Complications". The Journal of Pain. 1 (4): 245–57. doi:10.1054/jpai.2000.19408. PMID 14622605.

- ↑ Wei Y, Xu ZD, Li H (2020). "Quality of life after thoracic sympathectomy for palmar hyperhidrosis: a meta-analysis". General Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 68 (8): 746–753. doi:10.1007/s11748-020-01376-5. ISSN 1863-6705. PMID 32390086. S2CID 218562024.

- ↑ Dumont P (2008). "Side Effects and Complications of Surgery for Hyperhidrosis". Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 18 (2): 193–207. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.01.007. PMID 18557592.

- 1 2 Dimitriadou V, Aubineau P, Taxi J, Seylaz J (1988). "Ultrastructural changes in the cerebral artery wall induced by long-term sympathetic denervation". Blood Vessels. 25 (3): 122–43. doi:10.1159/000158727. PMID 3359052.

- ↑ Verghese A (May 1968). "Some observations on the psychogalvanic reflex". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 114 (510): 639–42. doi:10.1192/bjp.114.510.639. PMID 5654139. S2CID 37969867.

- ↑ Wei HM, Sinha AK, Weiss HR (1 April 1993). "Cervical sympathectomy reduces the heterogeneity of oxygen saturation in small cerebrocortical veins". Journal of Applied Physiology. 74 (4): 1911–5. doi:10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1911. PMID 8514710.

- ↑ Goebel F, Füessl H (1983). "Mönckeberg's sclerosis after sympathetic denervation in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects". Diabetologia. 24 (5): 347–50. doi:10.1007/BF00251822. PMID 6873514.

- ↑ Beskrovnova NN, Makarychev VA, Kiseleva ZM, Legon'kaia, Zhuchkova NI (1984). "Morphofunctional changes in the myocardium following sympathectomy and their role in the development of sudden death from ventricular fibrillation". Vestnik Akademii Meditsinskikh Nauk SSSR (2): 80–5. PMID 6711115.

- ↑ Lai C, Chen W, Liu Y, Lee Y (2001). "Bradycardia and Permanent Pacing After Bilateral Thoracoscopic T2-Sympathectomy for Primary Hyperhidrosis". Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 24 (4): 524–5. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00524.x. PMID 11341096. S2CID 13586588.

- ↑ Faleiros AT, Maffei FH, Resende LA (2006). "Effects of cervical sympathectomy on vasospasm induced by meningeal haemorrhage in rabbits". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 64 (3a): 572–4. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2006000400006. hdl:11449/12367. PMID 17119793.

- ↑ "Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy". Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

- ↑ Lyra Rd, de Campos JR, Kang DW, Loureiro Md, Furian MB, Costa MG, Coelho Md (Nov 2008). "Diretrizes para a prevenção, diagnóstico e tratamento da hiperidrose compensatória" [Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis]. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia (in Portuguese). 34 (11): 967–77. doi:10.1590/s1806-37132008001100013. PMID 19099105.

- ↑ Mineo T (2010). Technical Advances in Mediastinal Surgery, An Issue of Thoracic Surgery Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 329. ISBN 9781455700721.

- ↑ Hashmonai M, Kopelman D (2003). "History of sympathetic surgery". Clinical Autonomic Research. 13: I6–9. doi:10.1007/s10286-003-1103-5. PMID 14673664. S2CID 21176791.

British Journal of Surgery 2004; 91: 264–269