| American Indian English | |

|---|---|

| Region | Indian Country |

Native speakers | 9,666,058 (2020 census)[1][2] |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

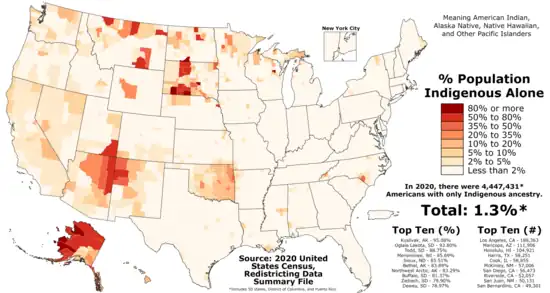

Population of Native Americans by country according to the 2020 United States census. Areas populated by Indigenous peoples are considered "Indian Country." | |

American Indian English or Native American English is a diverse collection of English dialects spoken by many American Indians and Alaska Natives,[3] notwithstanding indigenous languages also spoken in the United States, of which only a few are in daily use. For the sake of comparison, this article focuses on similarities across varieties of American Indian English that unite it in contrast to a "typical" English variety with standard grammar and a General American accent.

Pronunciation

Vowels

The phonemic contrasts between front vowels in standard English are not always maintained in American Indian dialects of English. For example, Navajo English may have KIT–DRESS, KIT–FLEECE, or FACE–DRESS mergers, particularly word-medially. Isleta English maintains these contrasts, though according to different patterns than standard English.[4] In the English of all Colorado River Indians (namely, Mohave, Hopi, and Navajo), front vowels tend to shift, often one degree lower than standard English vowels.[5]

Old speakers of Lumbee English share the PRICE vowel, and some other pronunciation and vocabulary features, in common with Outer Banks English, as well as some grammatical features in common with African-American Vernacular English.[6]

Consonants

Th-stopping is common in Cheyenne and Tsimshian English, and certainly many other varieties of Native American English: replacing initial /θ/ and /ð/ with /t/ and /d/, respectively.[7] Cheyenne and Navajo English, among others, follow General American patterns of glottal replacement of t, plus both t- and d-glottalization at the ends of syllables. The result is Brad fed the wet cat sounding like Bra' fe' the we' ca'.[8]

Pitch, intonation, and stress

Features of prosody substantially contribute to differences between American Indian and General American accents.[8] For example, even within the English of Colorado River Indians, there are differing rules for stress placement on words. However, these dialects do have similar intonation patterns, markedly different from General American: a lower level of pitch fluctuation and an absence of a rising intonation in questions. This is commonly stereotyped in American popular culture as a monotone, subdued, or emotionless sound quality.[9]

A 2016 study of various English-speaking indigenous North Americans (Slavey, Standing Rock Lakotas, and diverse Indian students at Dartmouth College) found that they all used uniquely shared prosodic features for occasional emphasis, irony, or playfulness in casual peer interactions, yet rarely in formal interactions. The prosodic choices are presumably a way for these speakers to index (tap into) a shared "Native" identity. The documented sounds of this "Pan-Indian" identity include higher pitch on post-stressed syllables (rather than stressed syllables); use of high-rising, mid, or high-falling (rather than simple falling) intonation at the ends of sentences; vowel lengthening at the ends of sentences; and syllable timing (instead of stress timing).[10]

Grammar

American Indian English shows enormous heterogeneity in terms of grammatical structures. As a whole, it characteristically uses plural and possessive markers less than standard English (for example, one of the dogs is here). Navajo, Northern Ute, and many other varieties of Indian English may simply never use plural markers for nouns.[11] Lack of other verb markers is commonly reported in Indian speech too, like an absence of standard English's "-ed" or "-s" endings for verb tense. Verbs like be, have, and get are also widely deleted, and some varieties of American Indian English add plural markers to mass nouns: thus, furnitures, homeworks, foods, etc. In general, verb constructions within American Indian English are distinctive and even vary wildly from tribe to tribe.[12]

Grammatical gender in pronouns (she, her, him, etc.) does not always align with the natural gender of a referent, particularly at the ends of sentences, in some American Indian English. For example, this is greatly documented in Mohave and Cheyenne English.[13] Mohave and Ute English even delete implied pronouns altogether, as in I didn't know where you were, was too busy to look, waited for you at school, but weren't there.).[14]

See also

References

- ↑ "Overview of 2020 AIAN Redistricting Data: 2020" (PDF). Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ↑ "Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census". Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 44.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 45.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 46.

- ↑ Wolfram, Walt (2006). American voices: how dialects differ from coast to coast. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 247.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 48–49.

- 1 2 Leap 1993, p. 50

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 52.

- ↑ Newmark, Kalina; Walker, Nacole; Stanford, James (2017). " 'The Rez Accent Knows No Borders': Native American Ethnic Identity Expressed through English Prosody". Language in Society 45 (5): 633–64.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 55.

- ↑ Leap 1993, pp. 62–4, 70.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 59.

- ↑ Leap 1993, p. 60.

Works cited

- Leap, William (1993). American Indian English. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874804164.