| Part of a series on |

| Renaissance music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

|

|

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers.[1] The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number of voices varies from two to eight, but usually features three to six voices, whilst the metre of the madrigal varies between two or three tercets, followed by one or two couplets.[2] Unlike the verse-repeating strophic forms sung to the same music,[3] most madrigals are through-composed, featuring different music for each stanza of lyrics, whereby the composer expresses the emotions contained in each line and in single words of the poem being sung.[4]

As written by Italianized Franco–Flemish composers in the 1520s, the madrigal partly originated from the three-to-four voice frottola (1470–1530); partly from composers' renewed interest in poetry written in vernacular Italian; partly from the stylistic influence of the French chanson; and from the polyphony of the motet (13th–16th c.). The technical contrast between the musical forms is in the frottola consisting of music set to stanzas of text, whilst the madrigal is through-composed, a work with different music for different stanzas.[5] As a composition, the madrigal of the Renaissance is unlike the two-to-three voice Italian Trecento madrigal (1300–1370) of the 14th century, having in common only the name madrigal,[6] which derives from the Latin matricalis (maternal) denoting musical work in service to the mother church.[2]

Artistically, the madrigal was the most important form of secular music in Italy, and reached its formal and historical zenith in the later 16th century, when the madrigal also was taken up by German and English composers, such as John Wilbye (1574–1638), Thomas Weelkes (1576–1623), and Thomas Morley (1557–1602) of the English Madrigal School (1588–1627). Although of British temper, most English madrigals were a cappella compositions for three to six voices, which either copied or translated the musical styles of the original madrigals from Italy.[2] By the mid 16th century, Italian composers began merging the madrigal into the composition of the cantata and the dialogue; and by the early 17th century, the aria replaced the madrigal in opera.[6]

History

Origins and early madrigals

The madrigal is a musical composition that emerged from the convergence of humanist trends in 16th-century Italy. First, renewed interest in the use of Italian as the vernacular language for daily life and communication, instead of Latin. In 1501, the literary theorist Pietro Bembo (1470–1547) published an edition of the poet Petrarch (1304–1374); and published the Oratio pro litteris graecis (1453) about achieving graceful writing by applying Latin prosody, careful attention to the sounding of words, and syntax, the positioning of a word within a line of text. As a form of poetry, the madrigal consisted of an irregular number of lines (usually 7–11 syllables) without repetition.[6][7][8]

Second, Italy was the usual destination for the oltremontani ("those from beyond the Alps") composers of the Franco-Flemish school, who were attracted by Italian culture and by employment in the court of an aristocrat or with the Roman Catholic Church. The composers of the Franco-Flemish school had mastered the style of polyphonic composition for religious music, and knew the secular compositions of their homelands, such as the chanson, which much differed from the secular, lighter styles of composition in late-15th- and early-16th-century Italy.[6]

Third, the printing press facilitated the availability of sheet music in Italy. The musical forms then in common use — the frottola and the ballata, the canzonetta and the mascherata — were light compositions with verses of low literary quality. Those musical forms used repetition and soprano-dominated homophony, chordal textures and styles, which were simpler than the composition styles of the Franco-Flemish school. Moreover, the Italian popular taste in literature was changing from frivolous verse to the type of serious verse used by Bembo and his school, who required more compositional flexibility than that of the frottola, and related musical forms.[6][8]

The madrigal slowly replaced the frottola in the transitional decade of the 1520s. The early madrigals were published in Musica di messer Bernardo Pisano sopra le canzone del Petrarcha (1520), by Bernardo Pisano (1490–1548), while no one composition is named madrigal, some of the settings are Petrarchan in versification and word-painting, which became compositional characteristics of the later madrigal.[6] The Madrigali de diversi musici: libro primo de la Serena (1530), by Philippe Verdelot (1480–1540), included music by Sebastiano Festa (1490–1524) and Costanzo Festa (1485–1545), Maistre Jhan (1485–1538) and Verdelot, himself.[6]

In the 1533–34 period, at Venice, Verdelot published two popular books of four-voice madrigals that were reprinted in 1540. In 1536, that publishing success prompted the founder of the Franco-Flemish school, Adrian Willaert (1490–1562), to rearrange some four-voice madrigals for single-voice and lute. In 1541, Verdelot also published five-voice madrigals and six-voice madrigals.[6] The success of the first book of madrigals, Il primo libro di madrigali (1539), by Jacques Arcadelt (1507–1568), made it the most reprinted madrigal book of its time.[9] Stylistically, the music in the books of Arcadelt and Verdelot was closer to the French chanson than the Italian frottola and the motet, given that French was their native tongue. As composers, they were attentive to the setting of the text, per Bembo's ideas, and through-composed the music, rather than use the refrain-and-verse constructions common to French secular music.[10]

Mid-16th century

Although the madrigal originated in the cities of Florence and Rome, by the mid 16th-century Venice had become the centre of musical activity. The political turmoils of the Sack of Rome (1527) and the Siege of Florence (1529–1530) diminished that city's significance as a musical centre. In addition, Venice was the music publishing centre of Europe; the Basilica of San Marco di Venezia (St. Mark's Basilica) was beginning to attract musicians from Europe; and Pietro Bembo had returned to Venice in 1529. Adrian Willaert (1490–1562) and his associates at St. Mark's Basilica, Girolamo Parabosco (1524–1557), Jacques Buus (1524–1557), and Baldassare Donato (1525–1603), Perissone Cambio (1520–1562) and Cipriano de Rore (1515–1565), were the principal composers of the madrigal at mid-century.

Unlike Arcadelt and Verdelot, Willaert preferred the complex textures of polyphonic language, thus his madrigals were like motets, although he varied the compositional textures, between homophonic and polyphonic passages, to highlight the text of the stanzas; for verse, Willaert preferred the sonnets of Petrarch.[6][11][12] Second to Willaert, Cipriano de Rore was the most influential composer of madrigals; whereas Willaert was restrained and subtle in his settings for the text, striving for homogeneity, rather than sharp contrast, Rore used extravagant rhetorical gestures, including word-painting and unusual chromatic relationships, a compositional trend encouraged by the music theorist Nicola Vicentino (1511–1576).[9][13] From Rore's musical language came the madrigalisms that made the genre distinctive, and the five-voice texture which became the standard for composition.[14]

1550s–1570s

The latter history of the madrigal begins with Cipriano de Rore, whose works were the elementary musical forms of madrigal composition that existed by the early 17th century.[6][15] The relevant composers include Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594), who wrote secular music in his early career; Orlande de Lassus (1530–1594), who wrote the twelve-motet Prophetiae Sibyllarum (Sibylline Prophecies, 1600), and later, when he moved to Munich in 1556, began the history of madrigal composition beyond Italy; and Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), the most prolific madrigalist, first published in 1554.[6][16]

In Venice, Andrea Gabrieli (1532–1585) composed madrigals with bright, open, polyphonic textures, as in his motet compositions. At the court of Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara (r. 1559–1597), there was the Concerto delle donne (1580–1597), the concert of the ladies, three women singers for whom Luzzasco Luzzaschi (1545–1607), Giaches de Wert (1535–1596), and Lodovico Agostini (1534–1590) composed ornamented madrigals, often with instrumental accompaniment. The great artistic quality of the Concerto delle donne of Ferrara encouraged composers to visit the court at Ferrara, to listen to women sing and to offer compositions for them to sing. In turn, other cities established their own concerto delle donne, as at Firenze, where the Medici family commissioned Alessandro Striggio (1536–1592) to compose madrigals in the style of Luzzaschi.[6] In Rome, the compositions of Luca Marenzio (1553–1599) were the madrigals that came closest to unifying the different styles of the time.[17]

In the 1560s, Marc'Antonio Ingegneri (1535–1592) — Monteverdi's instructor — Andrea Gabrieli (1532–1585), and Giovanni Ferretti (1540–1609) re-incorporated lighter elements of composition to the madrigal; serious Petrarchan verse about Love, Longing, and Death was replaced with the villanella and the canzonetta, compositions with dance rhythms and verses about a care-free life.[9] In the late 16th century, composers used word-painting to apply madrigalisms, passages in which the music matches the meaning of a word in the lyrics; thus, a composer sets riso (smile) to a passage of quick, running notes that mimic laughter, and sets sospiro (sigh) to a note that falls to the note below. In the 17th century, acceptance of word-painting as a musical form had changed, in the First Book of Ayres (1601), the poet and composer Thomas Campion (1567–1620) criticised word-painting as a negative mannerism in the madrigal: "where the nature of everie word is precisely expresst in the Note ... such childish observing of words is altogether ridiculous."[18]

Turn of the century

At the end of the 16th century, the changed social function of the madrigal contributed to its development into new forms of music. Since its invention, the madrigal had two roles: (i) a private entertainment for small groups of skilled, amateur singers and musicians; and (ii) a supplement to ceremonial performances of music for the public. The amateur entertainment function made the madrigal famous, yet professional singers replaced amateur singers when madrigalists composed music of greater range and dramatic force that was more difficult to sing, because the expressed sentiments required soloist singers of great range, rather than an ensemble of singers with mid-range voices.

There emerged the division between the active performers and the passive audience, especially in the culturally progressive cities of Ferrara and Mantua. The emotions communicated in a madrigal in 1590, an aria expressed in opera at the beginning of the 17th century, yet composers continued using the madrigal into the new century, such as the old-style madrigal for many voices; the solo madrigal with instrumental accompaniment; and the concertato madrigal, of which Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) was the most famous composer.[6]

In Naples, the compositional style of the pupil Carlo Gesualdo followed from the style of his mentor, Luzzasco Luzzaschi (1545–1607), who had published six books of madrigals and the religious music Responsoria pro hebdomada sancta (Responsories for Holy Week, 1611). In the early 1590s, Gesualdo had learnt the chromaticism and textural contrasts of Ferrarese composers, such as Alfonso Fontanelli (1557–1622) and Luzzaschi, but few madrigalists followed his stylistic mannerism and extreme chromaticism, which were compositional techniques selectively used by Antonio Cifra (1584–1629), Sigismondo d'India (1582–1629), and Domenico Mazzocchi (1592–1665) in their musical works.[6][19][20] In the 1620s, Gesualdo's successor madrigalist was Michelangelo Rossi (1601–1656), whose two books of unaccompanied madrigals display sustained, extreme chromaticism.[21]

Transition to the concertato madrigal

In the transition from Renaissance music (1400–1600) to Baroque music (1580–1750), Claudio Monteverdi usually is credited as the principal madrigalist whose nine books of madrigals showed the stylistic, technical transitions from the polyphony of the late 16th century to the styles of monody and of the concertato accompanied by basso continuo, of the early Baroque period. As an expressive composer, Monteverdi avoided the stylistic extremes of Gesualdo's chromaticism, and concentrated upon the drama inherent to the madrigal musical form. His fifth and sixth books include polyphonic madrigals for equal voices (in late-16th-century style) and madrigals with solo-voice parts accompanied by basso continuo, which feature unprepared dissonances and recitative passages — foreshadowing the compositional integration of the solo madrigal to the aria. In the fifth book of madrigals, using the term seconda pratica (second practice) Monteverdi said that the lyrics must be "the mistress of the harmony" of a madrigal, which was his progressive response to Giovanni Artusi (1540–1613) who negatively defended the limitations of dissonance and equal voice parts of the old-style polyphonic madrigal against the concertato madrigal.[22][23]

Transition from the concertato madrigal

In the first decade of the 17th century, the Italian compositional techniques for the madrigal progressed from the old ideal of an a cappella vocal composition for balanced voices, to a vocal composition for one or more voices with instrumental accompaniment. The inner voices became secondary to the soprano and the bass line; functional tonality developed, and treated dissonance freely for composers to emphasise the dramatic contrast among vocal groups and instruments. The 17th-century madrigal emerged from two trends of musical composition: (i) the solo madrigal with basso continuo; and (ii) the madrigal for two or more voices with basso continuo. In England, composers continued to write ensemble madrigals in the older, 16th-century style.[22][6] In 1600, the harmonic and dramatic changes in the composition of the madrigal expanded to include instrumental accompaniment, because the madrigal originally was composed for group performance by talented, amateur artists, without a passive audience; thus instruments filled the missing parts. The composer usually did not specify the instrumentation; in The Fifth Book of Madrigals and in the Sixth Book of Madrigals, Claudio Monteverdi indicated that the basso seguente, the instrumental bass part, was optional in the ensemble madrigal. The usual instruments for playing the bass line and filling inner voice parts, were the lute, the theorbo (chitarrone), and the harpsichord.[22][6]

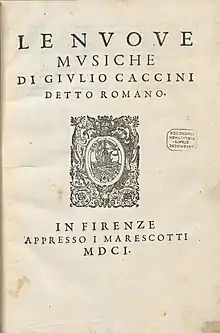

The madrigalist Giulio Caccini (1551–1618) produced madrigals in the solo continuo style, compositions technically related to monody and descended from the experimental music of the Florentine Camerata (1573–1587). In the collection of solo madrigals, Le nuove musiche (The New Music, 1601), Caccini said that the point of the composition was anti-contrapuntal, because the lyrics and words of the song were primary, and balanced-voice polyphony interfered with hearing the lyrics of the song. After Caccini's developments, the composers Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643), Sigismondo d'India (1582–1629), and Claudio Saracini (1586–1630) also published collections of madrigals in the solo continuo style. Whereas Caccini's music mostly was diatonic, later composers, especially d'India, composed solo continuo madrigals using an experimental idiom of chromaticism. In the Seventh Book of Madrigals (1619), Monteverdi published his only madrigal in the solo continuo style, which uses one singing voice, and three groups of instruments — a great technical advance from Caccini's simple voice-and-basso-continuo compositions from the 1600 period.[6]

Beginning around 1620, the aria supplanted the monodic-style madrigal. In 1618, the last, published book of solo madrigals contained no arias, likewise in that year, books of arias contained no madrigals, thus published arias outnumbered madrigals, and the prolific madrigalists Saracini and d'India ceased publishing in the mid-1620s.[6]

In the late 1630s, two madrigal collections summarised the compositional and technical practises of the late-style madrigal. In Madrigali a 5 voci in partitura (1638), Domenico Mazzocchi collected and organised madrigals into continuo and ensemble works specifically composed for a cappella performance. For the first time in a collection of madrigal music, Mazzocchi published precise instructions, including the symbols for crescendo and decrescendo; however, those madrigals were for musicologic study, not for performance, indicating composer Mazzochi's retrospective review of the madrigal as an old form of musical composition.[24] In the Eighth Book of Madrigals (1638), Monteverdi published his most famous madrigal, the Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, a dramatic composition much like a secular oratorio, featuring musical innovations such as the stile concitato (agitated style) that employs the string tremolo. In the event, the evolution of musical composition eliminated the madrigal as a discrete musical form; the solo cantata and the aria supplanted the solo continuo madrigal, and the ensemble madrigal was supplanted by the cantata and the dialogue, and, by 1640, the opera was the predominant dramatic musical form of the 17th century.[22]

English madrigal school

In 16th-century England, the madrigal became greatly popular upon publication of Musica Transalpina in (Transalpine Music, 1588), by Nicholas Yonge (1560–1619) a collection of Italian madrigals with corresponding English translations of the lyrics, which later initiated madrigal composition in England. The unaccompanied madrigal survived longer in England than in Continental Europe, where the madrigal musical form had fallen from popular favour, but English madrigalists continued composing and producing music in the Italian style of the late-16th century.

In early 18th-century England, the singing of madrigals was revived by catch clubs and glee clubs, leading to an upsurge of interest in the form[25][26] and creation of musical institutions such as the Madrigal Society, which was established in London by attorney and amateur musician John Immyns in 1741.[27] In the 19th century, the madrigal was the best-known music from the Renaissance (15th–16th c.) consequent to the prolific publishing of sheet music in the 16th and 17th centuries, even before the rediscovery of the madrigals of the composer Palestrina (Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina).[6]

Continental Europe

In the 16th century, the musical form of the Italian madrigal greatly influenced secular music throughout Europe, which composers wrote either in Italian or in their native tongues. The extent of madrigalist musical influence depended upon the cultural strength of the local tradition of secular music. In France, the native composition of the chanson disallowed the development of a French-style madrigal; nonetheless, French composers such as Orlande de Lassus (1532–1594) and Claude Le Jeune (1528–1600) applied madrigalian techniques in their musics.[6] In the Netherlands, Cornelis Verdonck (1563–1625), Hubert Waelrant (1517–1595), and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) composed madrigals in Italian.[6]

In German-speaking Europe, the prolific composers of madrigals included Lassus in Munich and Philippe de Monte (1521–1603) in Vienna. The German-speaking composers who studied the Italian techniques for composing madrigals, especially in Venice, included Hans Leo Hassler (1564–1612) who studied with Andrea Gabrieli, and Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672) who studied with Giovanni Gabrieli. From northern Europe, Danish and Polish court composers went to Italy to learn the Italian style of madrigal; while Luca Marenzio (1553–1599) went to the Polish court to work as the maestro di cappella (Master of the chapel) for King Sigismund III Vasa (r. 1587–1632) in Warsaw.[6] Moreover, the rektor of the University of Wittenberg, Caspar Ziegler (1621–1690) and Heinrich Schütz wrote the treatise Von den Madrigalen (1653).[28]

Madrigalists

Trecento madrigal

Early composers

- Jacques Arcadelt – I Libro a 4, 1543. Author of the most reprinted book of madrigals.

- Francesco Corteccia – court composer to Cosimo I de Medici

- Costanzo Festa – I Libro a 3, 1541.

- Bernardo Pisano

- Cypriano de Rore- I Libro a 5, 1542

- Philippe Verdelot – I Libro a 5, 1535. One of the first madrigalists, also associated with the Medici court

- Adrian Willaert – Franco-Flemish composer, founder of the Venetian School

Late Renaissance composers

- Andrea Gabrieli – I Libro a 3, 1575

- Orlando di Lasso

- Francisco Leontaritis

- Philippe de Monte – author of the largest number of madrigal books.

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina – famous mostly for his sacred music, he also wrote at least 140 secular madrigals.

- Giovan Leonardo Primavera

At the Baroque threshold

- Camillo Cortellini – I Libro a 5 e 6, 1583

- Carlo Gesualdo – I Libro, 1594

- Sigismondo d'India – I Libro a 5, 1606

- Luzzasco Luzzaschi – I Libro a 5, 1571

- Luca Marenzio – I Libro a 5, 1580

- Claudio Monteverdi – I Libro a 5, 1587

- Giaches de Wert – I Libro a 5, 1558

Baroque madrigalists

The a capella old-style madrigal for four or five voices continued in parallel with the new concertato style of madrigal, but the compositional watershed of the seconda prattica provided an autonomous basso continuo line, presented in the Fifth Book of Madrigals (1605), by Claudio Monteverdi.

Italy

- Agostino Agazzari – I Libro a 5, 1600

- Adriano Banchieri

- Giulio Caccini

- Antonio Cifra – I Libro a 5, 1605

- Sigismondo d'India

- Marco da Gagliano – I Libro a 5, 1602

- Alessandro Grandi

- Marco Marazzoli

- Domenico Mazzocchi – Madrigali a 5, 1638

- Claudio Monteverdi

- Giovanni Priuli – I Libro, 1604

- Paolo Quagliati – I Libro a 4, 1608

- Michelangelo Rossi

- Salamone Rossi – I Libro a 5, 1600. His Secondo Libro, 1602, is the first example of madrigals published with continuo.

- Claudio Saracini

- Barbara Strozzi – I Libro a 2-5vv with bc, 1644

- Orazio Vecchi – I Libro a 6, 1583

Germany

- Hans Leo Hassler – I Libro, 1600

- Johann Hermann Schein

- Heinrich Schütz – I Libro a 5, Venice 1611.

English madrigal school

- Thomas Bateson

- William Byrd

- John Dowland

- John Farmer

- Orlando Gibbons

- Thomas Morley

- Thomas Tomkins

- Thomas Weelkes

- John Wilbye

Some 60 madrigals of the English School are published in The Oxford Book of English Madrigals

English composers of the classical period

19th-century composers

20th-century composers

Contemporary

Musical examples

- Stage 1 Madrigal: Arcadelt, Ahime, dov'e bel viso, 1538

- Stage 2 Madrigal (prima practica): Willaert, Aspro core e selvaggio, mid-1540s

- Stage 3 Madrigal (seconda practica): Gesualdo, Io parto e non piu dissi, 1590–1611

- Stage 4 Madrigal: Caccini, Perfidissimo volto, 1602

- Stage 5 Madrigal: Monteverdi, Il Combatimento di Tancredi et Clorinda, 1624

- English Madrigal: Weelkes, O Care, thou wilt despatch me, late 16th century/early 17th century

- Nineteenth-century imitation of an English Madrigal: "Brightly dawns our wedding day" from the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera, The Mikado (1885)

References

Notes

- ↑ Hobson, James (2015). Musical antiquarianism and the madrigal revival in England, 1726-1851 (Ph.D.). University of Bristol. Retrieved 2 October 2022 – via EThOS.

- 1 2 3 J. A. Cuddon, ed. (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. p. 521.

- ↑ Tilmouth, Michael (1980), "Strophic", in Sadie, Stanley (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 18, London: Macmillan Press, pp. 292–293, ISBN 0-333-23111-2

- ↑ Scholes, Percy A. (1970). Ward, John Owen (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music (Tenth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-19-311306-6.

Durchkomponiert (G.) Through-composed; applied to songs with different music for every stanza, i.e. not merely a repeated tune.

- ↑ Brown 1976, p. 198

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 von Fischer & et al. 2001

- ↑ Atlas 1998, p. 433.

- 1 2 Brown 1976, p. 221

- 1 2 3 Randel 1986, p. 463

- ↑ Atlas 1998, pp. 431–432.

- ↑ Atlas 1998, pp. 432ff.

- ↑ Brown 1976, pp. 221–224.

- ↑ Brown 1976, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Einstein 1949, Vol. I, p. 391.

- ↑ Brown 1976, p. 228.

- ↑ Reese 1954, p. 406.

- ↑ Atlas 1998, pp. 636–638.

- ↑ Campion, Thomas. First Booke of Ayres (1601), quoted in von Fischer & et al. 2001

- ↑ Bianconi, Lorenzo; Watkins, Glenn (2001). Watkins, Glenn (ed.). "Gesualdo, Carlo, Prince of Venosa, Count of Conza". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10994. ISBN 9781561592630.

- ↑ Einstein 1949, Vol II, pp. 867–871.

- ↑ The Madrigals of Michelangelo Rossi, Brian Mann, Ed. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 Arnold & Wakelin 2011

- ↑ Artusi 1950, p. 395.

- ↑ Bukofzer, Manfred R. (1947). Music in the Baroque Era: From Monteverdi to Bach. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 37. OCLC 318558558. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ Lovell, Percy (1979). "'Ancient' Music in Eighteenth-Century England". Music & Letters. Oxford University Press. 60 (4): 401–415. doi:10.1093/ml/60.4.401. JSTOR 733505 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Day, Thomas (1972). "Old Music in England, 1790-1820". Revue Belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap. Societe Belge de Musicologie. 26/27: 25–37. doi:10.2307/3686537. JSTOR 3686537 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Craufurd, J. G. (1956). "The Madrigal Society". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association (82nd session). Taylor & Francis. 82: 33–46. doi:10.1093/jrma/82.1.33. ISSN 0080-4452. JSTOR 765866 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Von den Madrigalen. Leipzig: Digitalisat. 1653.

Sources

- Arnold, Denis; Wakelin, Emma (2011). "Madrigal". In Alison Latham (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. (subscription required)

- Artusi, Giovanni (1950). "Della imperfezioni della moderna musica". Source Readings in Music History. Translated by Oliver Strunk. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Atlas, Allan W. (1998). Renaissance Music: Music in Western Europe, 1400–1600. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97169-4.

- Brown, Howard Mayer (1976). Music in the Renaissance. Prentice Hall History of Music Series. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-608497-4.

- Einstein, Alfred (1949). The Italian Madrigal (Three volumes). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09112-9.

- von Fischer, Kurt; D'Agostino, Gianluca; Haar, James; Newcomb, Anthony; Ossi, Massimo; Fortune, Nigel; Kerman, Joseph; Roche, Jerome (2001). "Madrigal". In L. Macy (ed.). Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40075. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription required)

- Randel, Don, ed. (1986). The New Harvard Dictionary of Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-61525-5.

- Reese, Gustav (1954). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09530-4.

Further reading

- Iain Fenlon and James Haar: The Italian Madrigal in the Early 16th Century: Sources and Interpretation. Cambridge, 1988

- Oliphant, Thomas, ed. (1837) La musa madrigalesca, or, A collection of madrigals, ballets, roundelays etc.: chiefly of the Elizabethan age; with remarks and annotations. London: Calkin and Budd

- Choral Public Domain Library contains scores for many madrigals

External links

- Gosse, Edmund William; Tovey, Donald Francis (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). p. 295.

- Early Music; free recordings of English Madrigals, free recordings of German Lieder and free recordings of Spanish Madrigals, from Umeå Academic Choir, Academic Computer Club, Umeå University, Sweden

- The Italian Madrigal Resource Center