| Magnus IV & VII | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Magnus on the title page of his Swedish national lawcode (issue 1430). | |

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 8 July 1319 – 15 February 1364 |

| Coronation | 21 July 1336[1] |

| Predecessor | Birger |

| Successor | Albert |

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | August 1319 – 1355 |

| Predecessor | Haakon V |

| Successor | Haakon VI |

| Born | April or May 1316 Norway |

| Died | 1 December 1374 (aged 58) Bømlafjorden, Norway (shipwreck) |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Bjelbo |

| Father | Eric, Duke of Södermanland |

| Mother | Ingeborg of Norway |

Magnus IV (April or May 1316 – 1 December 1374; Swedish Magnus Eriksson) was King of Sweden from 1319 to 1364, King of Norway as Magnus VII (including Iceland and Greenland) from 1319 to 1355, and ruler of Scania from 1332 to 1360. By adversaries he has been called Magnus Smek (English: Magnus the Caresser).

Referring to Magnus Eriksson as Magnus II is incorrect. The Swedish Royal Court lists three Swedish kings before him of the same name.[2][3] A few authors do not count Magnus Nilsson as a Swedish king (though the Royal Court does) and have thus called this king Magnus III.[4] He is the second longest-reigning monarch in Swedish history, only surpassed by the current king Carl XVI Gustaf, who surpassed Magnus in 2018.

Biography

Magnus was born in Norway[2] either in April or May 1316[5] to Eric, Duke of Södermanland, a son of Magnus III of Sweden and Ingeborg, a daughter of Haakon V of Norway. Magnus was elected king of Sweden on 8 July 1319, and acclaimed as hereditary king of Norway at the thing of the Haugating in Tønsberg in August of the same year. Under the regencies of his grandmother, Helwig of Holstein, and his mother, Ingeborg of Norway, the countries were ruled by Knut Jonsson and Erling Vidkunsson.

Magnus was declared to have come of age at 15 in 1331. This provoked resistance in Norway, where a statute from 1302 stipulated that a king came of age at the age of 20, and a rising by Erling Vidkunsson and other Norwegian nobles ensued. In 1333, the rebels submitted to King Magnus.

In 1332 the King of Denmark, Christopher II, died as a "king without a country" after he and his older brother and predecessor had pawned Denmark piece by piece. King Magnus took advantage of his neighbour's distress, redeeming the pawn for the eastern Danish provinces for a huge amount of silver, and thus became ruler also of Scania.

On 21 July 1336 Magnus was crowned king of both Norway and Sweden in Stockholm. This caused further resentment in Norway, where the nobles and magnates desired a separate Norwegian coronation. A second rising by members of the high nobility of Norway ensued in 1338.

In 1335 he married Blanche of Namur, daughter of John I, Marquis of Namur, and Marie of Artois, a descendant of Louis VIII of France. The wedding took place in October or early November 1335, possibly at Bohus castle. As a wedding gift Blanche received the province of Tunsberg in Norway and Lödöse in Sweden as fiefs. They had two sons, Eric and Haakon, plus at least two daughters who died in infancy and were buried at Ås Abbey.

_seal_1905.jpg.webp)

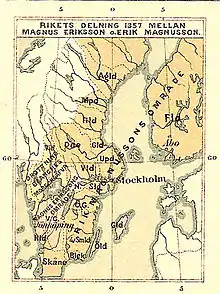

Opposition to Magnus' rule in Norway led to a settlement between the king and the Norwegian nobility at Varberg on 15 August 1343. In violation of the Norwegian laws on royal inheritance, Magnus' younger son Haakon would become king of Norway, with Magnus as regent during his minority. Later the same year, it was declared that Magnus' older son, Eric would become king of Sweden on Magnus' death. Thus, the union between Norway and Sweden would be severed. This occurred when Haakon came of age in 1355.

Because of the increase in taxes to pay for the acquisition of the Scanian province, some Swedish nobles supported by the Church attempted to oust Magnus, setting up his elder son Erik Magnusson as king (Eric XII of Sweden), but Eric died supposedly of the plague in 1359, with his wife Beatrice of Bavaria and their two sons.

Peace of Nöteborg

On 12 August 1323, Magnus concluded the first treaty between Sweden and Novgorod (represented by Grand Prince Yury of Moscow) at Nöteborg (Orekhov) where Lake Ladoga empties into the Neva River.[6] The treaty delineated spheres of influence among the Finns and Karelians and was supposed to be an "eternal peace", but Magnus' relations with Russia were not so peaceful. In 1337, religious strife between Orthodox Karelians and the Swedes led to a Swedish attack on the town of Korela (Keksholm, Priozersk) and Viborg (Viipuri in Finnish, Vyborg in Russian), in which the Novgorodian and Ladogan merchants there were slaughtered. A Swedish commander named Sten also captured the fortress at Orekhov. Negotiations with the Novgorodian mayor (posadnik) Fedor were inconclusive and the Swedes attacked Karelians around Lake Ladoga and Lake Onega before a peace was concluded in 1339 along the old terms of the 1323 treaty. In this treaty, the Swedes claimed that Sten and others acted on their own without the consent of the king.[7]

Outlawing thralldom (slavery)

In 1335, Magnus outlawed thralldom (slavery) for thralls "born by Christian parents" in Västergötland and Värend, being the last parts of Sweden where slavery had remained legal.[8] This put an end to Medieval Swedish slavery – though it was only applicable within the borders of Sweden, which left an opening – used long afterwards – for the 17th- and 18th-century Swedish slave trade.

Crusade against Novgorod

Relations were quiet between Sweden and Novgorod until 1348, when Magnus led a crusade against Novgorod, marching up the Neva, forcibly converting the tribes along that river, and briefly capturing the fortress of Orekhov for a second time.[9] The Novgorodians retook the fortress in 1349 after a seven-month siege, and Magnus fell back, in large part due to the ravages of the plague farther West. While he spent much of 1351 trying to drum up support for further crusading action among the German cities in the Baltic States, he never returned to attack Novgorod.[10]

Greenland

In 1355 Magnus sent a ship (or ships) to Greenland to inspect its Western and Eastern Settlements. Sailors found settlements entirely Norse and Christian. The Greenland carrier (Groenlands Knorr) made the Greenland run at intervals till 1369, when she sank and was apparently not replaced.[11]

Later years

King Valdemar IV of Denmark reconquered Scania in 1360. He went on to conquer Gotland in 1361. On 27 July 1361, outside the city of Visby, the main city of Gotland, the final battle took place. It ended in a complete victory for Valdemar. Magnus had warned the inhabitants of Visby in a letter and started to gather troops to reconquer Scania. Valdemar went home to Denmark again in August and took a lot of plunder with him. Either in late 1361 or early 1362 the inhabitants of Visby raised themselves against the few Danish that Valdemar left behind and killed them.

In 1363, members of the Swedish Council of Aristocracy, led by Bo Jonsson Grip, arrived at the court of Mecklenburg. They had been banished from Sweden after a revolt against King Magnus. At the nobles' request, Albert of Mecklenburg launched an invasion of Sweden supported by several German dukes and counts. Several Hanseatic cities and dukes in Northern Germany expressed support of the new king. Stockholm and Kalmar, with large Hanseatic populations, also welcomed the intervention. Albert was proclaimed King of Sweden and crowned on 18 February 1364. Magnus found refuge with his younger son in Norway, where he drowned in a shipwreck in Bømlafjorden in 1374. He had retained his sovereignty over Iceland until his death.

Evaluation of his reign

.jpg.webp)

In spite of his many formal expansions his rule was considered a period of decline both for the Swedish royal power and for Sweden as a whole. Foreign nations like Denmark (after its recovery in 1340) and Mecklenburg intervened and Magnus does not seem to have been able to counter internal opposition that arose. He was regarded as a weak king and criticised for giving favourites too much power.

Magnus's young favourite courtier was Bengt Algotsson, whom he elevated to Duke of Finland and Halland, as well as Viceroy of the province of Scania. Because homosexuality was a mortal sin and vehemently scorned at that time, rumours about the king's alleged love relationship with Algotsson, and other erotic escapades, were spread by his enemies, particularly by some noblemen who referred to mystical visions of St. Bridget. Bridget and these allegations caused Magnus in posterity to be given the epithet of Magnus smek (Magnus Caress) and caused him a lot of harm, but there is no factual basis for them in historical sources.[12][13] Another angle is that the epithet Caress had nothing to do with the allegations of homosexuality but was given because of his alleged foolishness and naivety, as smek at the time was an insult inferring such weakness.[14]

Russians drew up an allegedly autobiographical account known as the Testament of Magnus (Rukopisanie Magnusha) which was inserted into the Russian Sofia First Chronicle, composed in Novgorod; it claimed that Magnus did not, in fact, drown at sea, but saw the errors of his ways and converted to Orthodoxy, becoming a monk in a Novgorodian monastery in Karelia. The account is apocryphal.[15]

Popular culture

Most of the Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy by Sigrid Undset takes place in Norway during Magnus's reign. He appears in one scene, and is presented in a relatively critical manner.

See also

References

- ↑ Kings and Rulers of Sweden ISBN 91-87064-35-9 p. 22

- 1 2 Magnus 7 Eriksson (Norsk biografisk leksikon)

- ↑ Albrekt af Meklenburg och Magnus Eriksson, 1364–1371 (Berättelser ur svenska historien )

- ↑ Ulf Sundberg in Medeltidens svenska krig Stockholm 1999 ISBN 9189080262 p. 135 ff. (in Swedish)

- ↑ "499-500 (Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 17. Lux - Mekanik)". 1912.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika, the Fortress of Orekhov, and the Defense of Orthodoxy," in Alan V. Murray, Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2009):255

- ↑ Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika," 264–5.

- ↑ Träldom. Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 30. Tromsdalstind - Urakami /159-160, 1920. (In Swedish).

- ↑ Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika", 266–267.

- ↑ Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika," 268.

- ↑ Gwyn Jones, "The Vikings", Folio Society, London 1997, p.292.

- ↑ Libellus de Magno Erici Rege, in: Scriptores Rerum Svecicarum III,1, p.15–19

- ↑ Michael Nordberg in I kung Magnus tid ISBN 91-1-952122-7 p. 288

- ↑ Olle, Ferm (2009). Kung Magnus och hans smädenamn Smek.

- ↑ Sofiiskaia Pervaia Letopis' in Polnoe Sobranie Russkikh Letopisei, vol. 5 (St. Petersburg: Eduard Prats, 1851)

Further reading

- Mikael Nordberg, I kung Magnus tid (In the Times of King Magnus) ISBN 91-1-952122-7

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller, Magnus versus Birgitta : der Kampf der heiligen Birgitta von Schweden gegen König Magnus Eriksson, Hamburg 2003 (German)

External links

Media related to Magnus IV of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magnus IV of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons