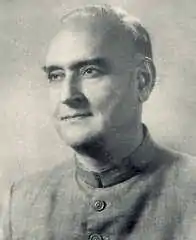

Mahmud Husain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister for Education | |

| In office 4 February 1953 – 17 April 1953 | |

| Prime Minister | Khawaja Nazimuddin |

| Preceded by | Fazlur Rahman |

| Succeeded by | Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi |

| Minister for Kashmir Affairs | |

| In office 26 November 1951 – 17 April 1953 | |

| Prime Minister | Khawaja Nazimuddin |

| Preceded by | Mushtaq Ahmed Gurmani |

| Succeeded by | Shuaib Qureshi |

| Minister of State for States and Frontier Regions | |

| In office 24 October 1950 – 24 October 1951 | |

| Prime Minister | Liaquat Ali Khan |

| Deputy Minister for Defense, Foreign Affairs and Finance | |

| In office 3 February 1949 – 24 October 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Liaquat Ali Khan |

| Member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan | |

| In office 10 August 1947 – 24 October 1954 | |

| Constituency | East Bengal |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 July 1907 |

| Died | 12 April 1975 (aged 67) Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan |

| Political party | Muslim League |

| Relatives |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

Mahmud Husain Khan (5 July 1907 – 12 April 1975) was a Pakistani historian, educationist, and politician, known for his role in the Pakistan Movement, and for pioneering the study of social sciences.[1] He served as Minister for Kashmir Affairs from 1951 to 1953 and Minister for Education in 1953.

As a member of the country's first Constituent Assembly, Husain served on Muhammad Ali Jinnah's parliamentary committee for fundamental rights and minorities. He was appointed Deputy Minister for Defence, Finance, and Foreign Affairs in 1949 and Minister of State for States and Frontier Regions in 1950 by Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. After becoming federal minister under Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin, he refused to rejoin the cabinet when Governor-General Ghulam Muhammad dismissed the Nazimuddin ministry. He quit politics when the Constituent Assembly was dissolved in 1954.

Returning to academia, Husain served as vice-chancellor of Dhaka University and later University of Karachi until his death in 1975. He founded Jamia Milia Islamia, Malir, modelled on the university of the same name founded by his brother, Zakir Husain. A proponent of greater rights for East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, Husain emerged a vocal but unsuccessful critic of Pakistan's military action in 1971.[2] University of Karachi renamed its library in his memory in 1976.

Early life and family

Mahmud Husain was born in Qaimganj, United Provinces, British India to Fida Husain Khan, a lawyer, and Naznin Begum.[3] The youngest of seven sons, he was the brother of Dr Zakir Husain, the third President of India, and scholar and historian Yusuf Husain. He was also the father of television compere Anwar Husain, uncle of academic Masud Husain Khan, and the father-in-law of General Rahimuddin Khan, the Governor of Balochistan. Mahmud Husain's family were ethnic Kheshgi and Afridi Pashtuns whose roots were in Tirah, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.[4] His ancestor Husain Khan migrated from Kohat to Qaimganj in 1715.[3]

Husain attended Islamia High School, Etawah and Aligarh Government High School. He was part of the first batch of students to be admitted into the newly established Jamia Milia Islamia, where he was heavily influenced by the ideas of Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar. He received his PhD from the University of Heidelberg in Germany in 1932.

Mahmud Husain started his career in academia as a reader of modern history at the University of Dhaka in 1933, where he became provost, Fazlul Haq Hall in 1944 and professor of international relations in 1948.

Political career

Pakistan Movement

Unlike his brother Zakir Husain, Mahmud Husain had been a strong proponent of the Pakistan Movement, and catalysed support for Pakistan among students in East Bengal and at Dhaka University. On Direct Action Day in 1946, Husain was charged with leading the pro-Pakistan rally in Dhaka.[5]

Member of the Constituent Assembly

He was elected Member of the first Constituent Assembly of Pakistan from East Bengal on the platform of Muslim League,[6] and also elected Secretary of the Muslim League's Parliamentary Group. He was included by Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan in the Basic Principles Committee, the main parliamentary group charged with drafting the underlying principles of the Constitution of Pakistan. He also served on the committee of minorities and fundamental rights.

Liaquat ministry

Husain was appointed both Deputy Minister for Defense and Foreign Affairs in the cabinet of Prime Minister Liaquat in 1949, before becoming State Minister for State and Frontier Regions a year later.[2] Following the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, Khawaja Nazimuddin assumed the post of prime minister.

Nazimuddin ministry

In the Nazimuddin ministry, Husain served as Minister for Kashmir Affairs from 26 November 1951 to 117 April 953, when he was appointed Minister for Education.[2] Following anti-Ahmadiyya riots in 1953, martial law was imposed in Lahore, and Governor-General Ghulam Muhammad dismissed Nazimuddin's government soon after. Husain along with Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar and Abdul Sattar Pirzada refused to join the new cabinet constituted by Ghulam Muhammad. He formally retired from politics in protest when the Constituent Assembly was dissolved in 1954.[7]

Academia

After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, Husain, inspired by the old Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India, played a key role in establishing an educational society Majlis-i-Taleem-i-Milli Pakistan in 1948 which served as the parent body of the Jamia Millia Educational Complex located in Malir, Karachi, Pakistan.In 1947,he was one of the pioneers in establishing Department of International Relations in University of Dhaka. It was the first IR department ever in any South Asian Universities. [8] Later in the early 1950s, over a 27 acres of land, many educational institutions were built at this Malir educational complex.[8]

Husain returned to academia in 1953, after the dismissal of National Assembly of Pakistan.[1] He joined Karachi University as its first professor of international relations and history. He also began the faculties of journalism and library science, the first in Pakistan.[9] Husain also laid the foundation of the Library Association in 1957 and served as its president for fifteen years. He instituted the greater induction of social sciences into the national curriculum.

Husain was a known supporter of greater rights for East Pakistan and was appointed vice-chancellor of the University of Dacca in 1960.[1] During his tenure until 1963, Husain refused government requests to intervene in mass student protests against President Ayub Khan and martial law. During and after his tenure, he became a vocal critic of the government's handling of East Pakistan, and urged integration.

He also taught as visiting professor at his alma mater Heidelberg University (1963–64), Columbia University (1964–65) and University of Pennsylvania (1965–66).[2] In 1966, Husain went back to the University of Karachi as professor of history and worked there as the dean of its Faculty of Arts until 1971. He served as vice-chancellor of the University of Karachi from 1971 to 1975.[1][10]

He strongly opposed the army operation in East Pakistan in 1971 but to no avail. He died while serving as vice-chancellor on 12 April 1975.

Works

Husain was fluent in Urdu, English, German, and Persian, writing primarily in the Urdu language. His Urdu translations are Mahida-i-Imrani (1935) from Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Social Contract, and Badshah (1947), a translation of Machiavelli's The Prince. His other books include The Quest for an Empire (1937), and Fatah-i-Mujahideen (1950), an Urdu translation of Zainul Abideen Shustri's Persian treatise on Tipu Sultan.[1] He was also editor of the A History of the Freedom Movement.

His best-known work is his English translation of Tipu's diaries from the original Persian, The Dreams of Tipu Sultan.

Eponyms

- Dr. Mahmud Husain Road, Jamshed Town, Karachi 24°52′21″N 67°3′54″E / 24.87250°N 67.06500°E[11]

- Mahmud Husain Library: On 12 April 1976, a year after his death, the Karachi University Syndicate renamed the Karachi University Library as the Dr. Mahmud Husain Library by unanimous resolution.[12][13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mahmud Hussain profile". Council of Social Sciences Pakistan (magazine website). April 2003. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Khan, Muazzam Hussain. "Khan, Mahamud Husain". Banglapedia. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- 1 2 Zia-ul-Hasan Faruqi (1999) Dr. Zakir Hussain: Quest for Truth APH Publishing, India, GoogleBooks website

- ↑ Sharma, Vishwamitra (2007). Famous Indians of the 21st century. Pustak Mahal. p. 60. ISBN 81-223-0829-5. Retrieved 30 August 2019

- ↑ Mahmud Husain's interview to Radio Pakistan on YouTube

- ↑ First Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (1947-1954) Government of Pakistan website, Retrieved 30 August 2019

- ↑ Callard, Keith (1957). Pakistan: A Political Study. London: George Allen & Unwin. pp. 135–136. OCLC 16879711.

- 1 2 Faiza Ilyas (18 February 2015). "Jamia Millia Malir body asked to vacate historical building". Dawn. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Recalling Our Pioneers, Council of Social Sciences Pakistan website

- ↑ Karachi University: Where it stands today The News International, Published 27 August 2008, Retrieved 30 August 2019

- ↑ Wikimapia.org

- ↑ University of Karachi Website

- ↑ Tehmina Qureshi (24 September 2012). "Key sources of national history gathering dust in Karachi University library". Dawn. Retrieved 30 August 2019.