| Major thirds | |

|---|---|

Each major-thirds tuning packs the octave's 12 notes into 3 strings' 4 frets. | |

| Basic information | |

| Aliases | All-thirds (M3) tuning Augmented tuning |

| Interval | Major third |

| Semitones | 4 |

| Example(s) | G♯–C–E–G♯–C–E |

| Advanced information | |

| Repetition | After 3 strings |

| Advantages | Octave on 4 frets, Major–minor chords on 2 |

| Disadvantages | Reduced range on 6 strings |

| Left-handed tuning | Minor-sixths tuning |

| Regular tunings (semitones) | |

| Trivial (0) | |

| Minor thirds (3) | |

| Major thirds (4) | |

| All fourths (5) | |

| Augmented fourths (6) | |

| New standard (7, 3) | |

| All fifths (7) | |

| Minor sixths (8) | |

| Guitar tunings | |

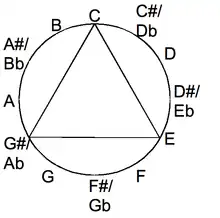

Among alternative tunings for guitar, a major-thirds tuning is a regular tuning in which each interval between successive open strings is a major third ("M3" in musical abbreviation).[1] Other names for major-thirds tuning include major-third tuning, M3 tuning, all-thirds tuning, and augmented tuning. By definition, a major-third interval separates two notes that differ by exactly four semitones (one-third of the twelve-note octave).

The Spanish guitar's tuning mixes four perfect fourths (five semitones) and one major-third, the latter occurring between the G and B strings:

- E–A–D–G–B–E.

This tuning, which is used for acoustic and electric guitars, is called "standard" in English, a convention that is followed in this article. While standard tuning is irregular, mixing four fourths and one major third, M3 tunings are regular: Only major-third intervals occur between the successive strings of the M3 tunings, for example, the open augmented C tuning.

- G♯–C–E–G♯–C–E.

For each M3 tuning, the open strings form an augmented triad in two octaves.

For guitars with six strings, every major-third tuning repeats its three open-notes in two octaves, so providing many options for fingering chords. By repeating open-string notes and by having uniform intervals between strings, major-thirds tuning simplifies learning by beginners. These features also facilitate advanced guitarists' improvisation,[2][3] precisely the aim of jazz guitarist Ralph Patt when he began popularizing major-thirds tuning between 1963 and 1964.

Avoiding standard tuning's irregular intervals

In standard tuning, the successive open-strings mix two types of intervals, four perfect-fourths and the major third between the G and B strings:

- E2–A2–D3–G3–B3–E4.

Only major thirds occur as open-string intervals for major-thirds tuning, which is also called "major-third tuning",[4][5] "all-thirds tuning",[6] and "M3 tuning".[7] The most viable M3 tunings are:

- E2-G#2-C3-E3-G#3-C4

- F2-A2-C#3-F3-A3-C#4

- F#2-A#2-D3-F#3-A#3-D4

- G2-B2-D#3-G3-B3-D#4

- G#2-C3-E3-G#3-C4-E4

All of these tunings reduce the overall range of the instrument a bit: the first takes a M3 off the top of the range, and the last takes a M3 off the bottom of the range. One popular M3 tuning has the open strings:

which some guitarists have applied to the top six strings of a seven string guitar, with the low seventh string tuned to the low E, to restore the standard E–E range.[8][9] While M3 tuning can use standard sets of guitar strings,[8] specialized string gauges have been recommended.[6][10] The middle tunings are a compromise, each losing a note or two off both the top and the bottom of the range. For example, for six-string guitars, the M3 tuning:

- F♯2–A♯2–D3–F♯3–A♯3–D4

loses the two lowest semitones on the low-E string and the two highest semitones from the high-E string in standard tuning; it can use string sets for standard tuning.[8]

Note that regardless of which note is chosen to start the tuning sequence, there are only four distinct sets of open-note pitch classes. The major-thirds tunings respectively have the open notes : {E, G#, C}, {F, A, C#},[5] {F#, A#, D}, and {G, B, D#}[8][5]

Properties

Major-thirds tunings require less hand-stretching than other tunings, because each M3 tuning packs the octave's twelve notes into four consecutive frets.[2][11] The major-third intervals allow major chords and minor chords to be played with two–three consecutive fingers on two consecutive frets.[12] Every major-thirds tuning is regular and repetitive, two properties that facilitate learning by beginners and improvisation by advanced guitarists.[2][3][13]

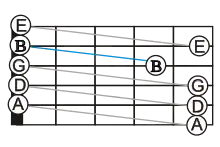

Four frets for the four fingers

In major-thirds tuning, the chromatic scale is arranged on three consecutive strings in four consecutive frets.[2][11] This four-fret arrangement facilitates the left-hand technique for classical (Spanish) guitar:[11] For each hand position of four frets, the hand is stationary and the fingers move, each finger being responsible for one fret.[14] Consequently, three hand-positions (covering frets 1–4, 5–8, and 9–12) partition the fingerboard of classical guitar,[9] which has exactly 12 frets.[note 1]

Only two or three frets are needed for the guitar chords—major, minor, and dominant sevenths—which are emphasized in introductions to guitar-playing and to the fundamentals of music.[15][16] Each major and minor chord can be played on two successive frets on three successive strings, and therefore each needs only two fingers. Other chords—seconds, fourths, sevenths, and ninths—are played on only three successive frets.[12] For fundamental-chord fingerings, major-thirds tuning's simplicity and consistency are not shared by standard tuning, whose seventh-chord fingering is discussed at the end of this section.

Repetition

Each major-thirds tuning repeats its open-notes after every two strings, which results in two copies of the three open-strings' notes, each in a different octave. This repetition again simplifies the learning of chords and improvisation.[2][3] This advantage is not shared by two popular regular-tunings, all-fourths and all-fifths tuning.[3]

Chord inversion is especially simple in major-thirds tuning. Chords are inverted simply by raising one or two notes three strings. The raised notes are played with the same finger as the original notes. Thus, major and minor chords are played on two frets in M3 tuning even when they are inverted. In contrast, inversions of chords in standard tuning require three fingers on a span of four frets,[17] in standard tuning, the shape of inversions depends on the involvement of the irregular major-third.[18]

Regular musical intervals

In each regular tuning, the musical intervals are the same for each pair of consecutive strings. Other regular tunings include all-fourths, augmented-fourths, and all-fifths tunings. For each regular tuning, chord patterns may be moved around the fretboard,[13] a property that simplifies beginners' learning of chords and advanced players' improvisation.[2][3][13]

In contrast, chords cannot be shifted around the fretboard in standard tuning, which requires four chord-shapes for the major chords: There are separate fingerings for chords having root notes on one of the four strings three–six.[19]

Shifting chords: Vertical and diagonal

The repetition of the major-thirds tuning enables notes and chords to be raised one octave by being vertically shifted by three strings.[5] Notes and chords may be shifted diagonally in major-thirds tuning, by combining a vertical shift of one string with a horizontal shift of four frets:[1][20] "Like all regular tunings, chords in the major third tuning can be moved across the fretboard (ascending or descending a major third for each string)...."[1]

In standard tuning, playing scales of one octave requires three patterns, which depend on the string of the root note.[21] Chords cannot be shifted diagonally without changing finger-patterns. Standard tuning has four finger-patterns for musical intervals,[19] four forms for basic major-chords,[22] and three forms for the inversion of the basic major-chords.[18]

Open chords and beginning players

Major-thirds tunings are unconventional open tunings, in which the open strings form an augmented triad. In M3 tunings, the augmented fifth replaces the perfect fifth of the major triad, which is used in conventional open-tunings.[1] For example, the C-augmented triad (C,E,G♯) has a G♯ in place of the C-major triad's G. (The note G♯ is enharmonically equivalent to A♭, as noted above.) Consequently, M3 tunings are also called (open) augmented-fifth tunings (in French "La guitare #5, majeure quinte augmentée").[23]

Instructional literature uses standard tuning.[3] Traditionally a course begins with the hand in first position,[24] that is, with the left-hand covering frets 1–4.[14] Beginning players first learn open chords belonging to the major keys C, G, and D. Guitarists who play mainly open chords in these three major-keys and their relative minor-keys (Am, Em, Bm) may prefer standard tuning over an M3 tuning.[25] In particular, hobbyists playing folk music around a campfire are well served by standard tuning. Such hobbyists may also play major-thirds tuning, which also has many open chords with notes on five or six strings;[26][27] chords with five-six strings have greater volume than chords with three-four strings and so are useful for acoustic guitars (for example, acoustic-electric guitars without amplification).

Intermediate guitarists do not limit themselves to one hand-position, and consequently open chords are only part of their chordal repertoire. In contemporary music, master guitarists "think diagonally and move up and down the strings"; fluency on the entire fretboard is needed particularly by guitarists playing jazz.[24] According to its inventor, Ralph Patt, major-thirds tuning

makes the hard things easy and the easy things hard. ... This is never going to take the place of folk guitar, and it's not meant to. For difficult music, and for where we are going in free jazz and even the old be-bop jazz, this is a much easier way to play.[9]

Left-handed chords

Major-thirds tuning is closely related to minor-sixths tuning, which is the regular tuning that is based on the minor sixth,[28] the interval of eight semitones. Either ascending by a major third or by descending by a minor sixth, one arrives at the same pitch class, the same note representing pitches in different octaves. Intervals paired like the pair of major-third and minor-sixth intervals are termed "inverse intervals" in the theory of music.[29] Consequently, chord charts for minor-sixths tunings may be used for left-handed major-thirds tunings; conversely, chord charts for major-thirds tunings may be used for left-handed minor-sixths tunings.[28]

Fingering of seventh chords

_tuning_for_six_string_guitar.svg.png.webp)

Major-thirds tuning facilitates playing chords with closed voicings. In contrast, standard tuning would require more hand-stretching to play closed-voice seventh chords, and so standard tuning uses open voicings for many four-note chords, for example of dominant seventh chords.[12] By definition, a dominant seventh is a four-note chord combining a major chord and a minor seventh. For example, the C7 seventh chord combines the C-major chord {C, E, G} with B♭. In standard tuning, extending the root-bass C-major chord (C,E,G) to a C7 chord (C, E, G, B♭) would span six frets (3–8);[30] such seventh chords "contain some pretty serious stretches in the left hand".[31] An illustration shows this C7 voicing (C, E, G, B♭), which would be extremely difficult to play in standard tuning,[30] besides the openly voiced C7-chord that is conventional in standard tuning:[30] This open-position C7 chord is termed a second-inversion C7 drop 2 chord (C, G, B♭, E), because the second-highest note (C) in the second-inversion C7 chord (G, B♭, C, E) is lowered by an octave.[30][32][note 2]

Disadvantages

While major thirds tuning confers the numerous advantages detailed above, it also introduces certain disadvantages, as compared to the instrument's standard tuning:

- M3 tuning decreases the overall range of the guitar (this is why some players eventually resorted to 7- and 8- string instruments, to regain that lost range)

- M3 simplifies the voicing of chords in close harmony, but it makes certain common voicings in open harmony more difficult, or even impossible

- M3 facilitates moving 3- and 4-note chords up or down an octave, but it makes the fingerings for 5- and 6-note multi-octave chords more complex and awkward.

History

Major-thirds tuning was introduced in 1964 by jazz guitarist Ralph Patt. He was studying with Gunther Schuller, whose twelve-tone technique was invented for atonal composition by his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg.[4] Patt was also inspired by the free jazz of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane.[4] Seeking a guitar tuning that would facilitate improvisation using twelve tones, he introduced major-thirds tuning by 1964,[3][7][33] perhaps in 1963.[4] To achieve the E−E open-string range of standard (Spanish) tuning,[9] Patt started using seven-string guitars in 1963, before settling on eight-string guitars with high G♯ (equivalently A♭) as their highest open-notes.[4] Patt used major-thirds tuning during all of his work as a session musician after 1965 in New York.[4] Patt developed a webpage with extensive information about major-thirds tuning.[34]

See also

- Minor-thirds tuning

- Repetitive open-tunings approximate M3 tunings:

- Non-Spanish classical guitars:

- Other open tunings

- Open A tuning: E–A–C♯–E–A–C♯ approximates F–A–C♯–F–A–C♯

- Open B tuning: F♯–B–D♯–F♯–B–D♯ approximates G–B–D♯–G–B–D♯

- Open C tuning: C–E–G–C–E–G approximates C–E–G♯–C–E–G♯

- Open D tuning: D–F♯–A–D–F♯–A approximates D–F♯–A♯–D–F♯–A♯

- Open E tuning: E–G♯–B–E–G♯–B approximates E–G♯–C–E–G♯–C

- Open F tuning: F–A–C–F–A–C approximates F–A–C♯–F–A–C♯

- Open G tuning: G–B–D–G–B–D approximates G–B–D♯–G–B–D♯

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 Classical guitars have 12 frets, while steel-string acoustics have 14 or more (Denyer 1992, p. 45). Electric guitars have more frets, for example 20 (Denyer 1992, p. 77).

- 1 2 The illustration designates B♭ by its enharmonic equivalent, A♯. Guitar fretboards use (twelve-tone) equal-temperament tuning, in which B♭ and A♯ denote the same pitch. These notes represent distinct pitches in tuning systems that are not equally tempered.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Sethares (2001, "The major third tuning" (pp. 56–57), p. 56)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Peterson (2002, pp. 36–37)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kirkeby (2012)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peterson (2002, p. 36)

- 1 2 3 4 Griewank (2010, p. 3)

- 1 2 Patt, Ralph (4 April 2004). "Tuning in all thirds". rec.music.makers.guitar.jazz. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- 1 2 Griewank (2010, p. 1)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Griewank (2010, p. 4)

- 1 2 3 4 Peterson (2002, p. 37)

- ↑ Kirkeby (2012, "Strings")

- 1 2 3 Griewank (2010, p. 9)

- 1 2 3 Griewank (2010, p. 2)

- 1 2 3 Sethares (2001, p. 52)

- 1 2 Denyer (1992, p. 72)

- ↑ Mead (2002, pp. 28 and 81)

- ↑ Duckworth (2007, p. 339)

- ↑ Griewank (2010, p. 10)

- 1 2 Denyer (1992, p. 121)

- 1 2 Denyer (1992, p. 119)

- ↑ Griewank (2010, pp. 9–10)

- ↑ Denyer (1992, p. 105)

- ↑ Denyer (1992, pp. 74–75)

- ↑ Zemb, Patrick (15 August 2007). "Sommaire du site musical (French: Summary of the musical site)". English machine-translation. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- 1 2 White (2005)

- ↑ Griewank (2010, p. 5)

- ↑ Griewank (2010, pp. 13, with listing on pp. 20–21)

- ↑ Sethares (2001, "The major third tuning" (pp. 56–57), listing on p. 57)

- 1 2 Sethares (2001, p. 53)

- ↑ Duckworth (2007, pp. 128–129)

- 1 2 3 4 Smith (1980, pp. 92–93)

- ↑ Kolb (2005, p. 37)

- ↑ Fisher (2002, pp. 30–33)

- ↑ Patt (2008)

- ↑ Sethares (2012)

Bibliography

- Denyer, Ralph (1992) [1982]. "Playing the guitar". The guitar handbook: The essential encyclopedia for every guitar player. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford (Fully revised and updated ed.). London and Sydney: Pan Books. pp. 65–160. ISBN 978-0330327503.

- Duckworth, William (2007). A creative approach to music fundamentals: Includes keyboard and guitar insert (ninth ed.). Thomson Schirmer. pp. 1–384. ISBN 9780495090939.

- Fisher, Jody (2002). "Chapter Five: Expanding your 7 chord vocabulary". Jazz guitar harmony: Take the mystery out of jazz harmony. Alfred Music Publishing. pp. 26–33. ISBN 9780739024683.

- Griewank, Andreas (1 January 2010), Tuning guitars and reading music in major thirds, Matheon preprints, vol. 695, Berlin: DFG research center "MATHEON, Mathematics for key technologies", MSC-Classification 97M80 Arts. Music. Language. Architecture. urn:nbn:de:0296-matheon-6755. Postscript file and Pdf file

- Kirkeby, Ole (1 March 2012). "Major thirds tuning". m3guitar.com. cited by Sethares (2012) and Griewank (2010, p. 1). Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Kolb, Tom (2005). Music theory. Hal Leonard Guitar Method. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 1–104. ISBN 978-0634066511.

- Mead, David (2002). Chords and scales for guitarists. London: Bobcat Books Limited: SMT. ISBN 978-1860744327.

- Patt, Ralph (14 April 2008). "The major 3rd tuning". Ralph Patt's jazz web page. ralphpatt.com. cited by Sethares (2012) and Griewank (2010, p. 1). Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Peterson, Jonathon (2002). "Tuning in thirds: A new approach to playing leads to a new kind of guitar". American Lutherie: The Quarterly Journal of the Guild of American Luthiers. Tacoma, Washington: The Guild of American Luthiers. 72 (Winter): 36–43. ISSN 1041-7176. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Sethares, Bill (2001). "Regular tunings". Alternate tuning guide (PDF). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Engineering. pp. 52–67. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Sethares, William A. (18 May 2012). "Alternate tuning guide". Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Engineering. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Smith, Johnny (1980). "XVII: Upper structure inversions of the dominant seventh chords". Mel Bay's complete Johnny Smith approach to guitar. Complete. Mel Bay Publications. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-15622-2239-0.

- White, Mark (2005). "Reading skills: The guitarist's nemesis?". Berklee Today. Boston, Massachusetts: Berklee College of Music. 72. ISSN 1052-3839.

Further reading

- Sethares, Bill (10 January 2009) [2001]. Alternate tuning guide (PDF). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Engineering. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

External links

- Wolfowitz, Kiefer (2 May 2013) [26 August 2012]. "Chord diagrams for major-thirds tuning" (PDF). Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation. Dictionary of chords (major, minor, dominant sevenths); diagrams of sevenths (major, minor, dominant, half-diminished) arising in the tertian harmonization of the major scale on C; etc. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Professors Andreas Griewank and William Sethares each recommend discussions of major-thirds tuning by two jazz-guitarists, (Sethares 2012, "Regular tunings") and (Griewank 2010, p. 1):

- Ole Kirkeby for 6- and 7-string guitars: Charts of intervals, major, minor, and dominant chords; recommended gauges for strings.

- Ralph Patt for 6-, 7-, and 8-string guitars: Charts of scales, chords, and chord-progressions; string gauges.

- Three other jazz-guitar websites:

- Oberlin, Alexandre (3 October 2012). "Tuning your guitar in major thirds: Tune afresh and improvise!". Clear chord-diagrams. (Available in French). Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Zemb, Patrick (15 August 2007). "Sommaire du site musical (French: Summary of the musical site)". English machine-translation. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Corman, Tony (23 August 2021). "M3 Guitar". Free downloadable method book. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Guitar Tunings Database (2012). "Major thirds". Tuner, scales, and chords for M3 tunings: G♯-C-E-G♯-C-E ("most popular") and F♯-A♯-D-F♯-A♯-D ("for beginners"). Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- Video tutorial on major and minor chords in major-thirds tuning on YouTube

- Bromley, Keith (October 2013). Chord shapes for major-thirds (M3) tuning on a 7-string guitar (PDF). Retrieved 9 November 2013.