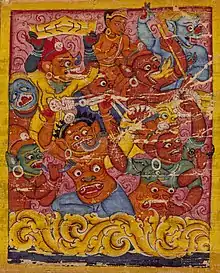

Mara (Sanskrit: मार, Māra; Sinhala: මාරයා; Chinese: 天魔; pinyin: Tiānmó or traditional Chinese: 魔羅; simplified Chinese: 魔罗; pinyin: Móluó; Japanese: 魔羅, romanized: Mara; also マーラ, Māra or 天魔, Tenma; Korean: 마라, romanized: Mara; Vietnamese: Thiên Ma; Tibetan Wylie: bdud; Khmer: មារ; Burmese: မာရ်နတ်; Thai: มาร; Tagalog: Mara), in Buddhism, is a malignant celestial king who tried to stop Prince Siddhartha from achieving Enlightenment by trying to seduce him with his celestial Army and the vision of beautiful women who, in various legends, are often said to be Mara's daughters.[1]

In Buddhist cosmology, Mara is associated with death, rebirth and desire.[2] Nyanaponika Thera has described Mara as "the personification of the forces antagonistic to enlightenment."[3]

Etymology

The word Māra comes from the Sanskrit form of the verbal root mṛ. It takes a present indicative form mṛyate and a causative form mārayati (with strengthening of the root vowel from ṛ to ār). Māra is a verbal noun from the causative root and means 'causing death' or 'killing'.[4] It is related to other words for death from the same root, such as: maraṇa and mṛtyu. The latter is a name for death personified and is sometimes identified with Yama.

The root mṛ is related to the Indo-European verbal root *mer meaning "die, disappear" in the context of "death, murder or destruction". It is "very wide-spread" in Indo-European languages suggesting it to be of great antiquity, according to Mallory and Adams.[5]

Four types of Māra

In traditional Buddhism, four or five metaphorical forms of Māra are given:[6]

- Kleśa-māra - Māra as the embodiment of all unskillful emotions, such as greed, hate and delusion.

- Mṛtyu-māra - Māra as death.

- Skandha-māra - Māra as metaphor for the entirety of conditioned existence.

- Devaputra-māra - the deva of the sensuous realm, who tried to prevent Gautama Buddha from attaining liberation from the cycle of rebirth on the night of the Buddha’s enlightenment.

Character

Early Buddhism acknowledged both a literal and psychological interpretation of Mara.[7][8]

Mara is described both as an entity having an existence in Kāma-world,[9] just as are shown existing around the Buddha, and also is described in pratītyasamutpāda as, primarily, the guardian of passion and the catalyst for lust, hesitation and fear that obstructs meditation among Buddhists. The Denkōroku refers to him as the "One Who Delights in Destruction", which highlights his nature as a deity among the Parinirmitavaśavarti devas.[10]

"Buddha defying Mara" is a common pose of Buddha sculptures.[11][12] The Buddha is shown with his left hand in his lap, palm facing upwards and his right hand on his right knee. The fingers of his right hand touch the earth, to call the earth as his witness for defying Mara and achieving enlightenment. This posture is also referred to as the bhūmisparśa "earth-witness" mudra.

Three daughters

In some accounts of the Buddha's enlightenment, it is said that the demon Māra did not send his three daughters to tempt but instead they came willingly after Māra's setback in his endeavor to eliminate the Buddha's quest for enlightenment.[13] Mara's three daughters are identified as Taṇhā (Thirst), Arati (Aversion, Discontentment), and Rāga (Attachment, Desire, Greed, Passion).[12][14] For example, in the Samyutta Nikaya's Māra-saṃyutta, Mara's three daughters were stripping in front of Buddha; but failed to entice the Buddha:

- They had come to him glittering with beauty –

- Taṇhā, Arati, and Rāga –

- But the Teacher swept them away right there

- As the wind, a fallen cotton tuft.[15]

Some stories refer to the existence of Five Daughters, who represent not only the Three Poisons of Attraction, Aversion, and Delusion, but also include the daughters Pride, and Fear.

Mara's conversion

The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp and the Denkoroku both contain a story of Mara's conversion to Buddhism under the auspices of the monk Upagupta.

According to the story, Upagupta journeyed to the kingdom of Mathura and preached the Dharma with great success. This caused Mara's palace to tremble, prompting the deity to use his destructive powers against the Dharma. When Upagupta entered samadhi, Mara approached him and slipped a jade necklace around his neck.

Upagupta reciprocated by transforming the corpses of a man, a dog, and a snake into a garland and gifted it to Mara. When Mara discovered the true nature of the gift, he sought the help of Brahma to remove it. Brahma informed him that because the necklace was bestowed by an advanced disciple of the Buddha, its effects could only be assuaged by taking refuge in Upagupta.

Mara returned to the human world where he prostrated before the monk and repented. At Upagupta's recommendation, he vowed never to do harm to the Dharma and took refuge in the Three Jewels.[16]

The former source includes a gatha that Mara recited when his suffering was lifted:

Adoration to the Master of the three samādhis,

To the sage disciple of the ten powers.

Today I wish to turn to him

Without countenancing the existence

Of any meanness or weakness.[17]

In popular culture

Mara has been prominently featured in the Megami Tensei video game series as a demon. Within the series, Mara is portrayed as a large, phallic creature, often shown riding a golden chariot. His phallic body and innuendo-laden speech are based on a pun surrounding the word mara, a Japonic word for "penis" that is attested as early as 938 CE in the Wamyō Ruijushō, a Japanese dictionary of Chinese characters. According to the Sanseido dictionary, the word was originally used as a euphemism for "penis" among Buddhist monks, which references sensual lust as an obstacle to enlightenment.[18]

The Doctor Who serials Kinda and Snakedance feature a villain called the Mara.

Mara is featured in the Disneyland version of the dark ride attraction Indiana Jones Adventure.

Mara appears in Roger Zelazny's novel Lord of Light as a god of illusion.[19]

In 2020, the singer-songwriter Jack Garratt released a song entitled "Mara". Inspired by the story of Mara’s distraction of the Buddha, "Mara" describes Garratt's experience of intrusive thoughts.[20]

Girl from Nowhere's Protagonist, Nanno–is inspired by Mara. Nanno's full name is actually Mara Amatayakul.

See also

- Demiurge

- Eros

- Grīmekhalaṃ

- Kamadeva

- Mare

- Marzanna

- Mors (mythology)

- Thanatos

- Anubis

- Izanami

- Hades

- Ah Puch

- Id, ego and super-ego

- Temptation of Christ and Temptation of St. Anthony (similar themes in Christianity)

- Maravijaya attitude (A Buddharupa attitude depicting the scene against Mara)

- Indiana Jones Adventure (A dark-ride at Disneyland and Tokyo DisneySea)

- Mayasura

Notes

- ↑ See, for instance, SN 4.25, entitled, "Māra's Daughters" (Bodhi, 2000, pp. 217–20), as well as Sn 835 (Saddhatissa, 1998, page 98). In each of these texts, Mara's daughters (Māradhītā) are personified by sensual Craving (taṇhā), Aversion (arati), and Passion (rāga).

- ↑ Trainor, Kevin (2004). Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780195173987.

- ↑ Thera, Nyanaponika (2008). The Roots of Good and Evil: Buddhist Texts translated from the Pali with Comments and Introduction. Buddhist Publication Society. p. 22. ISBN 9789552403163.

- ↑ Olson, Carl (2005). The Different Paths of Buddhism: A Narrative-Historical Introduction. Rutgers University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780813537788.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 150–153. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ↑ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 530–531, 550, 829. ISBN 9780691157863.

- ↑ Williams, Paul (2005). Buddhism: The early Buddhist schools and doctrinal history ; Theravāda doctrine, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780415332286.

- ↑ Keown, Damien (2009). Buddhism. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 69. ISBN 9781402768835.

- ↑ www.wisdomlib.org (10 August 2008). "Mara, Māra: 13 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org.

- ↑ Jokin, Keizan; Nearman, Hubert (translator) (2003). "The Denkōroku: The Record of the Transmission of the Light" (PDF). Mount Shasta, California: OBC Shasta Abbey Press. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Vogel, Jean Philippe; Barnouw, Adriaan Jacob (1936). Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon, and Java. Asian Educational Services. pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 "The Buddha's Encounters with Mara the Tempter: Their Representation in Literature and Art". www.accesstoinsight.org.

- ↑ Keown, Damien (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780191579172.

- ↑ See, e.g., SN 4.25 (Bodhi, 2000, pp. 217–20), and Sn 835 (Saddhatissa, 1998, p. 98). In a similar fashion, in Sn 436 (Saddhatissa, 1998, p. 48), taṇhā is personified as one of Death's four armies (senā) along with desire (kāmā), aversion (arati) and hunger-thirst (khuppipāsā).

- ↑ SN 4.25, v. 518 (Bodhi, 2000, p. 220).

- ↑ Jokin, Keizan; Nearman, Hubert (translator) (2003). "The Denkōroku: The Record of the Transmission of the Light" (PDF). Mount Shasta, California: OBC Shasta Abbey Press. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Daoyuan; Whitfield, Randolph S. (translator) (2015). Yi, Yang (ed.). Record of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume One. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 9783738662467.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ↑ "摩羅(まら)とは - Weblio辞書". www.weblio.jp.

- ↑ "Lord of Light Summary". Shmoop. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ↑ "Mara Inspiration". ladygunn. 5 February 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

Sources

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Pubs. ISBN 0-86171-331-1.

- Saddhatissa, H. (translator) (1998). The Sutta-Nipāta. London: RoutledgeCurzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0181-8.

Further reading

- Boyd, James W. (1971). "Symbols of Evil in Buddhism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 31 (1): 63–75. doi:10.2307/2053052. JSTOR 2053052. S2CID 162777343. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Guruge, Ananda W.P. (1991). "The Buddha's encounters with Mara, the Tempter: their representation in Literature and Art" (PDF). Indologica Taurinensia. 17–18: 183–208. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2014.

- Ling, Trevor O. (1962). Buddhism and the Mythology of Evil: A Study in Theravada Buddhism. London: Allen and Unwin