Lex Cincia de donis et muneribus was a law reportedly passed in 204 BC by the tribune Marcus Cincius Alimentus, so documented in Livy.[1][2] Few provisions of the law are known. One prohibited someone from giving an orator a gift to plead a case. Another limited the value of gifts that could be exchanged between different groups of people. It was passed in the aftermath of the second Punic war, probably for the purpose of reining in aristocratic families' demands for gifts from clients. It may also be related to a similar law, the lex Fufia testamentaria, which limited inheritances of non-blood relatives to 1,000 asses.[3]

Motivation

The law was passed in the aftermath of the Second Punic War. Per Cicero, the law was proposed in 204 BC by Marcus Cincius Alimentus as a plebiscite, with the support of the famous senator Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, who spoke in favour of it.[4]

Most scholars believe that the purpose of the law was not to limit consumption (a sumptuary law), but rather, was intended (as reported by Livy) to restrict the ability of patrons to extract gifts from their clients for various services.[5] In this context, the lex Cincia has been connected to the lex Fufia testamentaria (prohibiting bequests in wills of more than 1,000 asses to non-blood relatives) and the lex Publicia (restricting the value of gifts given on Saturnalia).[3][6]

Legal effect

The most important effect of the law, in retrospect, was its prohibition on the giving of gifts in exchange for legal advocacy or services.[7] The other main effects were those on gift-giving in general: gifts to those outside a rather large circle of exempted persons with amount greater than that set in the statute were prohibited.[8] A fragment of the law in a commentary on the praetorian edict by Julius Paulus Prudentissimus dealt with the exceptions: gifts between blood relatives, up to the fifth degree, were excepted, persons under the power of a pater familias (eg children-in-power, wives given into the husband's power, and some freedmen) could also exchange gits within that family. Transfers to and from slave peculia were also exempted, as were gifts as part of dowries.[9] However, the law was imperfecta, as the law made no provisions to nullify any gifts given in violation of its provisions; gifts to lawyers, however, later was attached with a fine.[10]

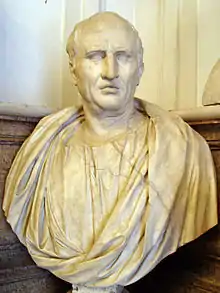

The law itself was administered by the praetor, who could grant an pleadable defence to a defendant who was being sued on the promise of a gift not yet handed over.[11] Regardless, by the late republic, the law's provisions were largely ignored by advocates: famous advocates such as Hortensius and Cicero made fortunes from their legal work. Hortensius was given an ivory sphinx for his defence of Gaius Verres even though Verres was convicted; Cicero, for defending Publius Cornelius Sulla from charges of being part of the Catilinarian conspiracy, was lent two million sesterces on generous terms so he could purchase a house on the Palatine hill. Cicero was shortly thereafter lent millions more by Gaius Antonius Hybrida (his consular colleague in 63 BC) for an unsuccessful defence on charges of corruption.[12][13]

In a letter to his friend Atticus, Cicero also joked about how a gift of books from Lucius Papirius Paetus had been approved after consultation with their mutual friend Cincius: "the joke here is that Cicero could not legally accept [it]... but since 'Cincius' himself said it was all right, Cicero pretends to have won an exemption ... the fact is that [Cicero] knows he is breaking the law and contrives a facetious and transparent excuse".[14] Cicero and others similarly received bequests from wealthy clients.[15] Few Romans – Cato the Elder and Pliny the Younger are so attested – actually followed the law's provisions.[16]

Fate

During the reign of Augustus, the penalty for legal services was set at four times the value of the gift itself.[17] Further action was taken by later emperors to limit lawyers' fees: Claudius capped fees to ten thousand sesterces; the later Edict on Maximum Prices issued during the reign of Diocletian similarly attempted to cap advocate fees.[18]

See also

References

- Citations

- ↑ Stein 1985, p. 145. Cf Tac. Ann. 11.5; Cic. Orat. 2.71.286, Att. 1.20.7; Liv. 34.4.9.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, p. 44.

- 1 2 Candy 2018; Stein 1985, p. 145.

- ↑ Candy 2018, citing Cic. De or. 2.71.286; Sen. 4.10.

- ↑ Candy 2018, citing Liv. 34.4.9.

- ↑ McGinn 2015, pp. 33 et seq.

- ↑ Candy 2018; Curchin 1983.

- ↑ McGinn 2015, p. 33.

- ↑ Candy 2018.

- ↑ Candy 2018, citing, Ulp. Reg. 1–2.

- ↑ Stein 1985, p. 145.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, pp. 40–42.

- ↑ Ps.-Sall. Cic. 4–5; Cic. Att. 1.12, 1.14.7.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, pp. 42–43, analysing and commenting on Cic. Att., 1.20.7.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, p. 43, citing, Boren, Henry C (1961). "The sources of Cicero's income: some suggestions". The Classical Journal. 57 (1): 17–24. ISSN 0009-8353.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, p. 45.

- ↑ Candy 2018, citing, Dio. 54.18.2.

- ↑ Curchin 1983, p. 38 n. 2, citing, Tac. Ann. 11.7, 13.5; Plin. Ep. 5.9.3, 5.13.8; Suet. Ner. 17.

- Sources

- Candy, Peter (2018-02-26). "lex Cincia on gifts". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8262. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- Curchin, Leonard A (1983). "The lex Cincia and lawyers' fees under the Republic". Echos du monde classique: Classical views. 27 (1): 38–45. ISSN 1913-5416.

- McGinn, Thomas AJ (2015). "The expressive function of law and the lex imperfecta" (PDF). Roman Legal Tradition. 11: 1–41. ISSN 1943-6483.

- Stein, P (1985). "Lex Cincia". Athenaeum. Pavia. 63: 145ff.